HENRY CLAY

April 12, 1777–June 29, 1852

WASHINGTON—How the concerns of life and death intermingle! Amid the hot contention of political strife, a slow, dull sound, filling every ear, brings the long expected annunciation that Henry Clay is no more. The greatest of American Senators has passed to the silent land, and each one who hears has a grief or a hope of his own. Last night bonfires illumined every street; shouts of anticipated victory and hoarse murmurs of defiance went up together; we seemed on the eve of a time, when

The midnight brought the signal sound of strife;

The morn, the marshaling in arms; the day,

Battle’s magnificently stern array!

But the morn brought only “the death in life,” its solemn silence and its awful gloom. The curtains were gathered around the dying couch of Henry Clay, and at 11 o’clock darkness had set its seal upon his eyes forever. This does but deepen the sadness of my heart, and consecrates my humble sorrow; for while moving with all this stirring life, and talking coldly of politics and its chances, a little thing that had twined among the tendrils of my inmost nature and nestled there was torn rudely from me. I see now its tiny hand and wavy hair, beckoning and leading the way to that unknown shore where the great and humble must together lie. But pardon this outburst.

The eulogies upon Mr. Clay will not be biographies; for none need be told where he was born, or what he has done. The facts of his life are engraven on the public memory. During the long months of his final illness the Nation’s heart has been to him a “Storied urn, an animated bust,” on which his “fame and elegy” are written. A niche is reserved for him in the temple consecrated to American statesmanship, eloquence and genius, opposite to Jefferson, Franklin, the elder and younger Adams, and Patrick Henry.

Mr. Clay was surrounded, in dying, by all that could inspire hope and alleviate sorrow. His son, several affectionate friends and physicians, and his spiritual consoler, Dr. Butler, of the Episcopal Church, were present. His last words were these, addressed to Dr. Butler: “Don’t leave me; I am dying, I am gone.” Instantly after speaking these words, he sank back and expired.

It is well known that Henry Clay received his early education in a log schoolhouse. At the age of 14 he went into a store, from which he soon after entered a law office as copyist, where at first his awkward manners, unhandsome face, and pepper-and-salt dress brought upon him jeers and jokes from his fellow clerks, who soon found it, however, their interest, as well as their pleasure, to treat him with respect.

The following toast, given in 1843, at a Fourth of July dinner in Virginia, by Mr. R. Hughes, illustrates some traits in his character and history:

“He walked barefooted, and so did I—he went to mill and so did I—he was good to his mamma and so was I. I know him like a book, and love him like a brother.”

Mrs. Watkins, the mother, died in 1827. Mr. Clay was always a man of deep feelings, and sustained heavy afflictions during life in the loss of his children. Two of his daughters, born in 1800 and 1816, died in infancy. Two other daughters, born in 1809 and 1813, died at the age of 14. The first of these died at Ashland; the other, in 1825, while on her way to Washington. On hearing of this fresh bereavement, Mr. Clay fainted, and did not leave his room for many days.

Mr. Clay always showed himself prompt to sympathize with persons in distress, and ever ready to aid the helpless. He often volunteered his legal services to rescue persons from slavery whom he believed to be unjustly held in bondage, and he never allowed any person to go undefended on account of poverty. He once found a poor Irishman named Russell, who had been lynched and beaten by a gang of persons calling themselves Regulators, and who had compelled him to abandon his house and property. Mr. Clay promptly interfered on his behalf, volunteered his services at great personal risk, and broke up the gang. Many other instances are recorded, of his having undertaken the defense of persons in distress—widows and orphans, who had not the means to employ other counsel.

Mr. Clay was as magnanimous as he was brave. He was quite as ready to acknowledge a fault as to resent an insult. In 1816, while he and Mr. [John] Pope were opposing candidates for Congress, Mr. Clay took offense at something which had been said by some of Mr. Pope’s friends and attacked him in the streets of Lexington. The next morning, satisfied he was wrong, he made an apology to the gentleman, and at a public gathering made the same acknowledgment. The magnanimity of the act, and the grace with which it was done, commended him anew to public favor.

Mr. Clay’s voice was one of remarkable compass, melody and power. It has often been remarked by spectators in the galleries of the Senate chamber that his ordinary tones in conversing at his desk could be heard more distinctly than the voices of other Senators who might be speaking at the time. He used this wonderful organ with powerful effect. His manner in speaking was marvelously graceful, full of action and energy, yet never for an instant failing in dignity, and admirably adapted to the special topic or mood of the moment.

Many persons are still living in Kentucky who heard his earliest popular harangues in that State, when he was merely a stripling—and according to their testimony, these efforts were marked by the same features which distinguished his maturer exertions. His arguments and appeals before juries in criminal cases, were long remembered as wonderful specimens of forensic eloquence.

No man, probably, ever had more of that quick penetration of intellect which enabled him instantly to seize the strong points of a case than Mr. Clay. His power over a jury was even more remarkable, and instances were frequent where he secured the acquittal of persons charged with murder, against the clearest evidence, simply through his resistless appeals to the sympathies of the jury. It is stated that no person put in peril of his life through the criminal code was ever defended by Mr. Clay without being saved.

In one case, a man named Willis, accused of a peculiarly atrocious murder, Mr. Clay succeeded in dividing the jury. Upon the second trial, Mr. Clay startled the audience by claiming a verdict on the sole ground that no man could be put in peril of his life twice for the same offense. The Court forbade the use of that argument, whereupon Mr. Clay took his papers and left the room, declaring he could not go on under such ruling. Finding the whole responsibility thus thrown upon him, the judge sent for him and invited his return. Mr. Clay came back, pressed that point, and secured an immediate acquittal on that ground alone.

Mr. Clay, as prosecuting attorney, once secured the conviction of a slave for murder, in a case where if he had been free, it would have been only manslaughter. He was so affected by the result that he resigned his commission in disgust.

We could fill column after column with such anecdotes. They all tend to illustrate the traits in the character of Mr. Clay, which were conspicuous throughout his life.

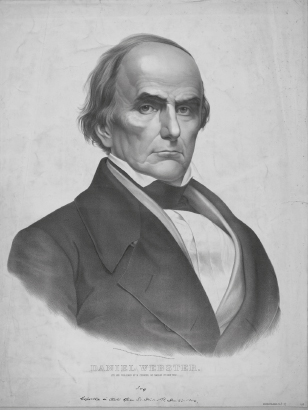

DANIEL WEBSTER

January 18, 1782–October 24, 1852

Daniel Webster, Secretary of State in the Government of the United States, died yesterday morning at 3 o’clock at his home in Marshfield, Massachusetts.

Thus has closed the most illustrious career which has yet graced the civil history of this Republic.

Daniel Webster was born in the town of Salisbury, New Hampshire, on the 18th of January, 1782. His age, at his death, was seventy years.

Ebenezer Webster, the father of the Great Statesman, was born in Kingston, New Hampshire, and served in the French War of 1763. He later commenced a settlement on a branch of the Merrimack River, eventually called Salisbury, and served in the state legislature and as a judge. His second wife, Abigail Eastman, was the mother of Daniel.

While still young, Daniel Webster was daily sent two miles and a half to school, in the middle of Winter, and on foot. In his 14th year, he was placed in Phillips’ Academy at Exeter, N.H.

In 1797, Daniel entered Dartmouth College. Upon graduation, he returned home, determined to adopt the profession of the law.

He was married in June, 1808, to Grace Fletcher. They had four children, of whom one survives.

Soon after the Declaration of War against England, Mr. Webster entered public life.

Mr. Webster took his seat in Congress in May, 1813, and was placed by Henry Clay, Speaker of the House, upon the Committee of Foreign Affairs. He delivered his maiden speech on 10th June, 1813, and in it a young man previously unknown in political circles made an indelible impression.

Great Britain then insisting upon her right of search in vessels belonging to the United States, and the mother country and her daughter were again embroiled in war.

Of the speeches of Mr. Webster on the Embargo, the politician Edward Everett said: “His speeches on these questions raised him to the front rank of debaters. He manifested upon his entrance into public life that variety of knowledge, familiarity with the history and traditions of the Government and self possession on the floor, which in most cases are acquired by time and long experience.”

Mr. Webster was reelected to the House of Representatives in August, 1814. In the Fall of 1822, he again took his seat in the House, this time representing the City of Boston.

Early in the session, the subject of the Revolution in Greece came before the House. Mr. Webster presented the following resolution: “That provision ought to be made by law, for defraying the expense incident to the appointment of an Agent or Commissioner to Greece.”

In his famous speech in support of this resolution, Mr. Webster showed himself a discriminating judge of the laws that govern the relations of nations. In sympathy for the struggling Greeks, he was not surpassed by any men of his time. He uttered a trumpet-toned remonstrance against the tyranny which sought their degradation. The “Greek Speech” will be remembered as long as American oratory has a place among the records of history.

In November, 1826, Mr. Webster was again solicited to represent his district in the House, but a vacancy occurred in the Senate, and Mr. Webster was chosen to fill that post.

Toward the close of 1827, a domestic affliction was visited upon Mr. Webster, in the loss of his wife, which prevented him from taking his seat until January, 1828.

Gen. [Andrew] Jackson was elected to the Presidency in the fall of 1828, and Mr. Calhoun, as Vice-President, occupied the Chair of the Senate.

In the Senatorial career of Mr. Webster, it is difficult to embrace all the great movements in which he took part.

One event in which Mr. Webster won laurels for himself was the part he took in the great controversy between the North and South—between the national views of the Constitution which he had often vindicated, and the doctrines of state rights, which had been enforced by Mr. Calhoun.

The first session of the 21st Congress opened in December, 1829. Attention was directed to the topic of the public lands. Both the North and the South sought to secure the political alliance of the Western states. Mr. Foote of Connecticut introduced a resolution proposing to limit the sale of public lands.

It has been alleged that this resolution was the starting point of a crusade against New England, and especially Mr. Webster.

The incidents that followed are so vividly presented in one of the chapters of Mr. March’s Reminiscences that we transfer it to our columns.

“It was on Tuesday, January the 26th, 1830, that the Senate resumed the consideration of Foote’s Resolution. As early as 9 o’clock of this morning crowds poured into the Capitol, in hot haste; at 12 o’clock, the hour of meeting, the Senate Chamber was filled to its utmost capacity. The very stairways were dark with men, who hung on to one another, like bees in a swarm.

“Mr. Webster was never more self possessed. The calmness of superior strength was visible everywhere; in countenance, voice and bearing. A deep-seated conviction of the extraordinary character of the emergency, and his ability to control it, seemed to possess him.”

Who can ever forget the tremendous burst of eloquence with which the orator spoke of the Old Bay State or his tones of pathos:

“Mr. President, I shall enter on no encomium upon Massachusetts. There she is—behold her, and judge for yourselves. There is her history: the world knows it by heart. The past, at least, is secure. There is Boston, and Concord, and Lexington, and Bunker Hill—and there they will remain forever. The bones of her sons, falling in the great struggle for independence, now lie mingled with the soil of every State, from New England to Georgia, and there they will lie forever. And, sir, where American Liberty raised its first voice, and where its youth was nurtured and sustained, there it still lives, in the strength of its manhood and full of its original spirit.”

No one ever looked the orator as he did. His swarthy countenance lighted up with excitement, he appeared amid the smoke, the fire, the thunder of his eloquence, like Vulcan in his armory forging thoughts for the Gods!

His voice penetrated every corner of the Senate as he pronounced these words:

“When my eyes shall be turned to behold, for the last time, the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent! on a land rent with civil feud, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the Republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced, its arms and trophies streaming in their original luster, not a stripe erased nor polluted, not a single star obscured, bearing for its motto no such miserable interrogatory as, ‘What is all this worth?’ Nor those other words of delusion and folly, ‘Liberty first, and Union afterwards;’ but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every American heart, Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

Mr. Webster’s “great speech,” as it is universally known, produced a sensation. The debate continued for weeks, but the argument had been exhausted.

Mr. Webster continued to take an active part in the debates of the Senate throughout the administration of General Jackson and his successor.

The 22nd Congress was faced with an issue of pressing importance. In South Carolina discontent under the Tariff [acts] had greatly increased. Large manufacturing interest had grown up in the Northern and Central States, while the South had not experienced similar benefits.

The South turned against the principle of protection, and its constitutionality had been denied. Mr. Calhoun had asserted the right of any State to nullify laws which she might consider unconstitutional. Mr. Webster had always maintained the supremacy of the Constitution and the Supreme Court of the United States as the final interpreter of its provisions.

Gen. Jackson was reelected President in the Fall of 1832; and the people of South Carolina were roused into the most intense excitement against the North and the protective policy. The Legislature declared the Tariff acts unconstitutional, and advised all citizens to put themselves in military array.

A bill was proposed that gave the President power to put down any armed resistance to the revenue laws of the United States. Upon this bill, and resolutions which he introduced, embodying his views on the right of a State to annul laws of Congress, Mr. Calhoun made the ablest argument ever advanced in support of his position.

Mr. Webster immediately entered upon a reply. In it he laid down the following propositions:

I. That the Constitution of the United States is not a compact between the people of the several States in their sovereign capacities, but a Government creating direct relations between itself and individuals.

II. That no State authority has power to dissolve those relations.

III. That there is a supreme law, consisting of the Constitution of the United States, acts of Congress, and treaties.

IV. That an attempt by a State to nullify an Act of Congress is a usurpation on the powers of the General Government and a violation of the Constitution.

The inauguration of Gen. [Benjamin] Harrison, in 1841, was the inauguration of a new era in the life of Mr. Webster, the one in which he became Secretary of State.

At the opening of the Congress of 1845, Mr. Webster resumed his seat in the Senate. He found under discussion some of the gravest questions that ever agitated the country.

The settlement of the Oregon boundary dispute was effected during the first year of Mr. Polk’s administration, by a division of the territory to which both England and the United States laid claim. A bill passed the House of Representatives to organize a Government for the territory thus acquired. When it reached the Senate, it was amended, by making the Missouri Compromise a part of it—excluding Slavery above, and admitting it below, the parallel of 36° 30’ north latitude.

On the 12th of August, 1848, Mr. Webster insisted upon the right of Congress to exclude slavery from this territory, and against any further extension of slave territory.

“The Southern States have peculiar laws, and by those laws there is property in slaves,” he said. “The real meaning, then, of Southern gentlemen, in making this complaint, is, that they cannot go into the territories of the United States carrying with them their own peculiar local law—a law which creates property in persons. This demand I, for one, shall resist.”

The bill passed with a clause forever excluding slavery from the territory.

Mr. Webster has achieved high distinction in three walks of life. Surpassed by few in the eloquence of his appeals to the jury, as a lawyer he stands unrivaled. As a statesman, no American except Alexander Hamilton can maintain a comparison with him. He loved his country, and he reverenced the Constitution. But Mr. Webster has achieved the highest rank as a literary man. All the products of his pen and the utterances of his tongue will be studied and admired by future ages.

And great as Mr. Webster was in all these spheres of intellectual activity, he was equally great in the department of conversation. We cannot imagine a richer contribution to the literature of America and the world than would be a record of Mr. Webster’s conversations upon topics of public concern.

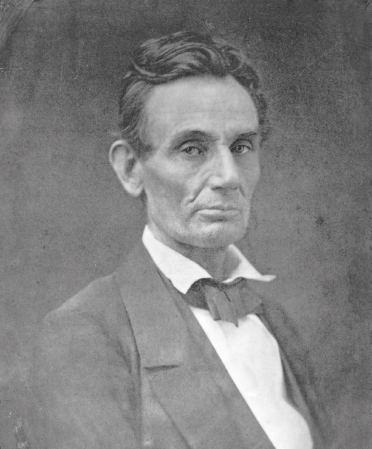

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

February 12, 1809–April 15, 1865

WASHINGTON—Abraham Lincoln died this morning at 22 minutes after 7 o’clock.

Official notice of the death of the late President Abraham Lincoln was given by the heads of departments this morning to Andrew Johnson, Vice-President. Mr. Johnson appeared before the Hon. Salmon P. Chase, Chief Justice of the United States, and took the oath of office, as President of the United States.

All business in the departments was suspended during the day.

It is now ascertained with reasonable certainty that two assassins were engaged in the horrible crime, Wilkes Booth being the one that shot the President, who was attending a performance at Ford’s Theatre, and the other, a companion of his, whose name is not known.

It appears from a letter found in Booth’s trunk that the murder was planned before the 4th of March, but fell through then because the accomplice backed out until “Richmond could be heard from.” Booth and his accomplice were at the livery stable at 6 o’clock last evening, and left there with their horses about 10 o’clock.

It would seem that they had for several days been seeking their chance, but it was not carried into effect until last night.

The murderers have not yet been apprehended. One of them has evidently made his way to Baltimore. The other has not yet been traced.

Two gentlemen, who went to the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, to apprize him of the attack on Mr. Lincoln, met at the residence of the former a man muffled in a cloak, who, when accosted by them, hastened away.

It had been the intention of Mr. Stanton to accompany Mr. Lincoln to the theatre, and occupy the same box, but the press of business prevented.

It seems evident that the aim of the plotters was to paralyze the country by at once striking down the head, the heart and the arm of the country.

As soon as the dreadful events were announced in the streets, Superintendent Richards and his assistants were at work to discover the assassin. Every road leading out of Washington was picketed, and every possible avenue of escape was guarded. Steamboats about to depart down the Potomac were stopped.

The Daily Chronicle says:

“As it is suspected that this conspiracy originated in Maryland, the telegraph flashed the mournful news to Baltimore, and all the cavalry was immediately put upon active duty. Every precaution was taken to prevent the escape of the assassin. Several persons were called to testify, and the evidence as elicited before an informal tribunal, and not under oath, was conclusive to this point:

“The murderer of President Lincoln was John Wilkes Booth. His hat was found in the private box, and identified by several persons who had seen him within the last two days, and the spur which he dropped by accident, after he jumped to the stage, was identified as one of those which he had obtained from the stable where he hired his horse.

Booth has played more than once at Ford’s Theatre, and is acquainted with its exits and entrances.”

Secretary of State Seward was also shot that evening, at his home, and the person who shot him left behind him a slouched hat and a rusty navy revolver.

Maunsell B. Field, assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury Department, gave this account of events:

“On Friday evening, April 14, 1865, I was reading the evening paper in Willard’s Hotel, at about 10½ o’clock, when I was startled by the report that an attempt had been made a few minutes before to assassinate the President at Ford’s Theatre.

“Immediately I proceeded to the scene of the alleged assassination. I found considerable crowds on the streets leading to the theatre, and a very large one in front of the theatre and the house directly opposite, where the President had been carried after the attempt upon his life.

“I obtained ingress to the house. I was informed that the President was dying; but I was desired not to communicate his condition to Mrs. Lincoln, who was in the front parlor. She appeared hysterical, and exclaimed over and over: “Oh, why didn’t he kill me?”

“I returned to Willard’s, it now being 2 o’clock in the morning, and remained there until between 3 and 4 o’clock, when I again went to the house where the President was. I proceeded at once to the bedroom on the parlor floor in which the President was lying.

“The bed was a double one, and the President lay diagonally across it. The pillows were saturated with blood. There was a patchwork coverlet thrown over the President, which was only so far removed as to enable the physicians in attendance to feel the arteries of the neck or the heart. The President was breathing regularly, and did not seem to be suffering.

“Among the persons present in the room were the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, the Postmaster-General, the Attorney-General, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of the Interior, the Assistant-Secretary of the Interior, Capt. Robert Lincoln, the President’s son, and Maj. John Hay.

“For several hours the breathing continued regularly. But about 7 o’clock a change occurred, and the breathing was interrupted at intervals, which became longer and more frequent. But not till 22 minutes past 7 o’clock in the morning did the flame flicker out.

“The President’s eyes after death were not entirely closed. I closed them myself with my fingers, and one of the surgeons brought pennies and placed them on the eyes, and subsequently substituted for them silver half-dollars.

“In fifteen minutes there came over the mouth a smile that seemed almost an effort of life. I had never seen upon the President’s face an expression more genial.

“About fifteen minutes before the decease, Mrs. Lincoln came into the room, and threw herself upon her dying husband’s body. She was allowed to remain there only a few minutes, when she was removed in a sobbing condition.

“Presently her carriage came up, and she was removed to it. She was in a state of tolerable composure until she reached the door, when, glancing at the theatre opposite, she repeated several times: ‘That dreadful house! That dreadful house!’”

The corpse of the late President has been laid out in the northwest wing of the White House. It is dressed in the suit of black clothes worn by him at his late Inauguration. A placid smile rests upon his features. White flowers have been placed over the breast.

The corpse of the President will be laid out in state in the east room on Tuesday, to give the public an opportunity to see once more the features of him they loved so well.

The catafalque upon which the body will rest will be placed there. The catafalque will be lined with fluted white satin, and the outside will be covered with black velvet. Steps will be placed at the side to enable the public to get a perfect view of the face.

The funeral ceremonies of the late President will take place on Wednesday next. The procession will form at 11 o’clock, and the religious service will commence at noon. The procession will move at 2 P.M.

The remains will be taken to Mr. Lincoln’s home at Springfield, Illinois.

The funeral car is to be a magnificent affair. The body of the car will be covered with black cloth from which will hang festoons of cloth fastened by rosettes of white and black satin over bows of white and black velvet. The bed of the car, on which the coffin will rest, will be eight feet from the ground, and over this will rise a canopy draped with black velvet.

A silver plate upon the coffin over the breast bears the following inscription:

ABRAHAM LINCOLN. SIXTEENTH PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, Born July 12, 1809. Died April 15, 1865.

A few locks of hair were removed from the President’s head for the family previous to the remains being placed in the coffin.

The Extra Star has the following:

“Developments have been made within the past twenty-four hours, showing the existence of a deep laid plot of a gang of conspirators to murder President Lincoln and his Cabinet. We have reason to believe that Secretary Seward received an intimation from Europe that something of a very desperate character was to transpire at Washington; and it is more than probable that the intimation had reference to the plot of assassination.

“The pickets encircling this city on Friday night to prevent the escape of the parties who murdered President Lincoln were fired upon at several points by concealed foes.

“It was ascertained some weeks ago that the late President had received several private letters warning him that an attempt would probably be made upon his life. But to this he did not seem to attach much, if any, importance.”

Abraham Lincoln was a great man, great intellectually. This was not universally admitted, but a brief glance at his career was sufficient to establish it. He was born in the humblest walks of life, had no advantages of education, had not been aided by any of those adventitious circumstances which assist so many others, and yet had gradually risen until he had reached the highest position in the State.

He had been a leading lawyer, a member of the Legislature of his own State, a member of Congress, the leader of his party in a memorable struggle for the Senatorship, and finally a successful candidate for the Presidency of the party that monopolizes the intelligence of the country. In his speeches delivered in his contest with Frederick Douglass are passages as noble and sublime as ever fell from the lips of any statesman in the country.

His lecture delivered in New York City, in the Cooper Union, in the midst of the learning and refinement of the metropolis, was universally admitted to be the ablest of the campaign. He was the first statesman to enunciate the great truth that the country could not exist partly slave and partly free.

In the discharge of his office, he bore himself with such a burden as no other President had ever borne, deciding questions the most difficult, giving gracious audience to the highest and the lowest, holding firmly the helm of affairs amid the stormiest seas, and conducting all to a successful issue.

The course of Mr. Lincoln for the past four years proves the possession of high intellectual endowments. Few men had ever had such opportunities to benefit their race. No other man since Washington had enjoyed such an opportunity of performing great services for his country.

The emancipating of the slaves was the golden attribute on which his future fame would rest. The Emancipation Proclamation will carry down his fame to the last syllable of recorded time. This had secured him the blessing of those who were ready to perish, and ensured for him such a preeminence among the great and good that he can never be forgotten.

The assassination has embalmed him in the grateful and lasting remembrance of mankind. He was above all a good man, an honest man. The country may well be thankful that one so scrupulous and conscientious was at the helm in these stormy times. He loved his fellow men. With the poor negro he was a demi-god. The bitterest tears shed over his grave will be by the race from whose manacled limbs he struck the fetters, and for whom he did so much.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

October 27, 1858–January 6, 1919

OYSTER BAY, L.I.,—Theodore Roosevelt, former President of the United States, died this morning at his home on Sagamore Hill.

His physicians said that the cause of death was a clot of blood which detached itself from a vein and entered the lungs.

A contributing cause was the fever he contracted during his explorations in Brazil, when he discovered the River of Doubt in 1914. This fever left a poison in the blood.

Colonel Roosevelt, who was 60, was working hard as late as Saturday, dictating articles and letters. He spent Sunday quietly, but looked and felt well, until shortly before 11 o’clock.

Colonel Roosevelt had no idea that he was seriously ill, and was full of plans for the future. When asked about his health by visitors, his reply was a vigorous “Bully!”

The village of Oyster Bay was stunned by the news. Colonel Roosevelt was appreciated by the village as a world figure, but he also was as much of a fellow townsman as the village blacksmith.

When Colonel Roosevelt returned from his South American journey, he gave the first account of his discoveries in an address at the local church, months ahead of the announcement of the discovery of the mysterious Brazilian River, now the Rio Teodoro, in a magazine. He was a village institution in the role of Santa Claus at the Cove Neck School, near Sagamore Hill.

Five airplanes from Quentin Roosevelt Field flew in “V” formation over Sagamore Hill in the afternoon and dropped wreaths of laurel about the house.

Only members of Colonel Roosevelt’s family and his intimate friends knew how deeply he suffered because of the death of Quentin, his youngest son, who was killed in combat in France on July 14. This is believed to have been a contributing cause of his death.

When the news was confirmed, Colonel Roosevelt, who had always declared that families should accept cheerfully the sacrifice of their sons in the war, issued a statement in which he said that he and Mrs. Roosevelt took pride in his death.

At his death Colonel Roosevelt carried in his body the bullet which was fired by Schrank, at Milwaukee, during the Presidential campaign of 1912, which nearly resulted in Colonel Roosevelt’s death because he went on and delivered his speech immediately after the attack.

Of all the accidents which Colonel Roosevelt went through, that which left the worst effects happened in South America. He tore his leg when he was thrown from a boat while descending the River of Doubt and the wound became badly infected. While ill from this he suffered an attack of fever.

Colonel Roosevelt was also partially blind and partially deaf. The sight of his left eye was destroyed while he was in the White House in a boxing match. The hearing of one ear was destroyed by an abscess. He was ordered by his physicians to give up violent exercise, but this advice he would not follow.

Mr. Roosevelt came from one of the oldest Dutch-American families. The founder of the family, Claes Martenzoon van Rosevelt, as the name was then spelled, came to this country in 1649.

His mother, Martha Bulloch, was a Southerner. His father, Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., was a philanthropist and the works he accomplished for the poor were legion.

The second Theodore Roosevelt was born in this city Oct. 27, 1858. He was graduated from Harvard in 1880, and was an officeholder almost continuously from 1882 until he retired from the Presidency in 1909.

As a boy he was puny and sickly; but with that indomitable determination which characterized his every act, he transformed his feeble body not merely into a strong one, but into one of the strongest. This physical feebleness bred in him nervousness and self-distrust, and in the same indomitable way he set himself to make himself a man of self-confidence and courage.

“When a boy,” he wrote in his autobiography, “I read a passage in one of Marryat’s books which always impressed me. In this passage the captain of some small British man-of-war is explaining to the hero how to acquire the quality of fearlessness. He says that at the outset almost every man is frightened when he goes into action, but that the course to follow is for the man to keep such a grip on himself that he can act just as if he was not frightened. After this is kept up long enough it changes from pretense to reality, and the man does in very fact become fearless by sheer dint of practicing fearlessness when he does not feel it.

“This was the theory upon which I went. There were all kinds of things of which I was afraid at first, ranging from grizzly bears to ‘mean’ horses and gunfighters; but by acting as if I was not afraid I gradually ceased to be afraid.”

After graduation he took up the study of law, but did not stay at it long. He entered politics, and at the age of 23 was elected to the Legislature. Within a year he was the Republican leader in the lower house. With a little band of men like himself, he fought for reform legislation, which at that time was generally regarded as a silk stocking freak. His biggest achievement was forcing an investigation of the crooked machine government of New York City, in which he acted as Chairman of the Investigating Committee, making a recalcitrant Legislature pass bills reforming some of the more flagrant abuses uncovered by the committee.

He served three terms in the Legislature, and in his third year came the great fight that split the Republican Party over the nomination of [James] Blaine for President. Roosevelt fought Blaine to the last ditch and, young as he was, was elected one of the four delegates-at-large to the National Convention, where he fought for the nomination of George F. Edmunds.

When Blaine was nominated, Mr. Roosevelt went off to become a rancher on the Little Missouri. At first the ranchers were disposed to laugh at the “four-eyed dude,” but they changed their opinion when they found that no work was too hard for him, no hardship too severe.

Mr. Roosevelt next attracted notice as a hunter of big game. Small game had no attraction for him, and it is doubtful whether he ever shot a rabbit. Only when the beast had some chance against the hunter did sport appeal to him, and the game that seemed most to his taste was the grizzly bear of the Rockies.

In 1880 President Harrison appointed him Civil Service Commissioner. For six years his constant warfare with the spoilsmen kept up as unending commotion among the politicians. He thought nothing of antagonizing even the greatest leaders in the Senate.

When he became President of the Commission, 14,000 Government offices were under civil service rules; when he left in 1895 to run the New York police, 40,000 offices were under civil service rules.

The election of Mayor [William Lafayette] Strong was caused by the Lexow exposures of police corruption in New York, and the new Mayor realized that the problem of police management would be the crucial one of his administration. He urged Mr. Roosevelt to become President of the New York Police Board.

Mr. Roosevelt was warned that the force was so honeycombed with favoritism and blackmail that the board could never ascertain the truth about what the men were doing. Roosevelt smiled and said: “Well, we will see about that,” and he personally sought the patrolmen on their beats at unexpected hours of the night, and whenever one was found derelict he was reprimanded or dismissed.

In April, 1897, he was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He became convinced that war with Spain was inevitable and proceeded to make provision for it. For command of the Asiatic Fleet, Mr. Roosevelt determined to get the appointment for Commodore [George] Dewey and secured the appointment which resulted in so much glory for the American Navy.

When the Spanish War broke out, Mr. Roosevelt resigned from the Navy Department to organize the famous Rough Riders. He did not feel justified in taking command of men, so he became Lieutenant Colonel. Before the campaign was over he felt warranted in taking the Colonelcy. The story of his prowess at Santiago is too well remembered to need rehearsing here.

When the war was over the soldiers were left in Cuba because of the slow arrangements of the War Department for transporting them home. The danger of pestilence among the Americans was great, and it was then that Col. Roosevelt demanded that the soldiers be taken home at once.

When they arrived at Montauk Point someone asked the Colonel about the state of his health. “I’m feeling as fit as a bull moose,” he replied. The simile would furnish a name to a political party.

He returned to the United States to find himself a popular idol, with a universal demand for his nomination for Governor of New York. He was elected by a majority of 18,000.

As Governor he consulted with [Thomas] Boss Platt, but the results of these consultations were what Roosevelt wanted and not what Platt wanted. Platt led an unhappy life while Roosevelt was Governor, and determined not to stand for another two years of it. He resorted to the expedient of kicking him upstairs into the Vice Presidency—little dreaming that he was paving the way to an elevation to the Presidency that would make Roosevelt even more of a thorn in Platt’s flesh.

Roosevelt was elected Vice President in 1900, but before the regular session of the Senate could meet, McKinley had been shot and Roosevelt was President. He was inaugurated at Buffalo Sept. 14, 1901.

The new President at once pledged himself to carry out President McKinley’s policies, and began by inviting the McKinley Cabinet to remain. Then three weeks after his inauguration, he invited Booker T. Washington, who was visiting the White House, to remain to luncheon. The South was up in arms in a moment, and the specter of social equality began to stalk, and it was long before Mr. Roosevelt could live down the impression that he was unfriendly to the South.

Economic questions at once engaged the President’s attention. In 1902 he settled the great anthracite coal strike by the unprecedented step of summoning the contending leaders to Washington and using the power of his personality and his office to influence them to a settlement and then by appointing the Coal Strike Commission.

In his message to Congress in 1902, he urged legislation for the control of trusts. About this time action was begun in the Federal courts against violations of the Sherman law, and Attorney General [Henry] Knox was pressing a suit to dissolve the Northern Securities Company.

Roosevelt jammed through Congress the so-called Elkins bill, which really was a Roosevelt bill and was designed to end the system of giving rebates to favored corporations who had to ship over this or that railroad. In addition, Roosevelt forced the creation of the Bureau of Corporations and invested it with authority to investigate all the corporate concerns in the country.

It was during his first administration that the Panama Canal was made possible. A treaty was eventually negotiated with the new Republic of Panama, and in May, 1904, the Canal Commission secured full control of the Panama Canal Zone and began operations.

He was nominated for President unanimously by the Republican Convention in 1904. Toward the close of the campaign he employed his famous “square deal” term, saying: “All I ask is a square deal. Give every man a fair chance.”

In the election that year he received the largest popular and Electoral vote ever given to a President up to that time.

In his first year he performed one of the greatest public acts of his career—the settlement of the Russo-Japanese war. For this the President received the Nobel Peace Prize. But he himself has always said that his greatest contribution to the cause of peace was sending the American fleet to the Pacific in 1907, an act he believed averted war between Japan and the United States.

In 1905 he began fighting for the regulation of railroad rates. In 1900 he had forced the Hepburn bill through Congress in the face of such bitter opposition from his own party that he was obliged to form an alliance with the Democrats. The latter charged bitterly that he threw them aside like a squeezed lemon when they had served his purpose. But he had no hesitation in breaking with the leaders of his own party, and had the satisfaction of putting his bill through.

His popularity now was at its greatest height, and by merely saying the word he could have had a third term. But on the night of his election in 1904 he had announced that he would under no circumstances accept another nomination.

He undertook to secure the nomination of his friend, William H. Taft, the Secretary of War.

Taft was nominated, and the President virtually took charge of his campaign. He planned, as soon as Taft was inaugurated, to leave the country and bury himself in Africa. But between the election and the inauguration a coolness had already sprung up between them.

Roosevelt perceived that Taft intended to change the Roosevelt policies and remove Roosevelt’s friends from office. The accounts that reached him as he emerged from the African jungle put the matter beyond a doubt, and when he reached the United States in June 1910, he was already an enemy of Taft.

The insurgent or progressive element in the Republican Party planned early in 1911 to defeat the renomination of President Taft, and it was decided to put forward Robert M. La Follette as the candidate. But a large element among the progressives wanted the nomination of Roosevelt.

At last, early in 1912, seven progressive Governors united in a demand that Roosevelt become a candidate. His answer was, “My hat is in the ring.”

President Taft went on the stump to defeat Roosevelt, but his own State [Ohio] went against him. When the Republican Convention met in Chicago, the bitterness between the factions was so great that predictions of rioting in the convention were made. [Taft ultimately received the nomination.]

The night the convention adjourned, Roosevelt’s followers proceeded to Orchestra Hall, where he was informally placed in nomination as a bolting candidate. But a real convention was held later, in August, at which the Progressive Party was formally created and Roosevelt was nominated for President.

The Colonel immediately began a stumping tour that took him through nearly every State in the Union. When Election Day arrived it was found that his achievement was something stupendous. Though his party was not born until two months after the regular party conventions, he had put the old Republican Party out of the running. Taft carried only the two small States of Utah and Vermont, while the Progressive Party had carried the great States of California, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and South Dakota. Roosevelt had over 4,000,000 votes.

[The Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson, won the election with a plurality of votes, defeating Roosevelt, Taft and the Socialist Party nominee, Eugene V. Debs.]

While the campaign was going on Col. Roosevelt was shot by a crank named John Schrank just as he was going to deliver a speech in Milwaukee. With astonishing courage, the Colonel insisted on going on with his speech. Then he was rushed to a hospital.

About this time Col. Roosevelt was invited to go to Argentina and deliver some lectures on economic problems. He accepted the invitation, and then decided that he would go into the hinterland and do some exploring and hunting.

He sailed on Oct. 4, 1913, and returned May 19, 1914, much weakened by jungle fever and after having had a narrow escape from death. It was while he was on his voyage of exploration up the Duvida River, which he discovered. He was so weakened by the fever that he could not go on. The party was almost without rations, reduced to five crackers each per day.

“This looks like the last for me, Doctor,” said the ex-President to Dr. Cajaziera. “If I’m to go, it’s all right. You see that the others don’t stop for me.” But he pulled through.

The Progressive Party was visibly going to the dogs in 1914. The pitiful figure they cut in the election of 1914 made it evident that as a party they had no future.

Then came our entrance into the war. “I and my four sons will go,” announced the Colonel. His four sons went, one of them to death, but he could not. The Administration was hostile to his proposal that he raise a division of volunteers, of which he would be brigadier general. This was the bitterest disappointment of his life.

Mr. Roosevelt was twice married. His first wife was Alice Hathaway Lee, who died in 1884. The only child of this marriage was Alice, the clever and attractive girl who became the wife of Congressman Nicholas Longworth.

In 1886 he married Edith Kermit Carow, and they had five children, Ethel, Theodore Jr., Kermit, Archibald and Quentin. The family life of the Roosevelts was ideal.

As an author Mr. Roosevelt has been prolific. His books include “The Winning of the West,” “Hunting Trips of a Ranchman,” “History of the Naval War of 1812,” “Life of Thomas Hart Benton,” “History of New York,” “The Wilderness Hunter,” “American Ideals,” “The Rough Riders,” and “The Strenuous Life.”

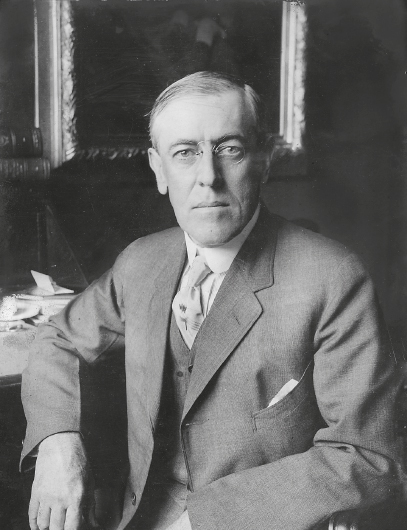

WOODROW WILSON

December 28, 1856–February 3, 1924

WASHINGTON—Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States, a commanding world figure and chief advocate of the League of Nations, is dead. He died at 11:15 o’clock this morning, after being unconscious for nearly twelve hours.

Mrs. Wilson, Miss Margaret Wilson, Joseph Wilson, a brother, and Admiral Grayson, his physician, were at the bedside.

Mr. Wilson’s last word was “Edith,” his wife’s name. In a faint voice he called for her yesterday afternoon when she had left his bedside for a moment. His last sentence was spoken on Friday, when he said: “I am a broken piece of machinery. When the machinery is broken—“I am ready.”

Mrs. Wilson held his right hand as his life slowly ebbed away.

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (he dropped the first name early in life) was born on Dec. 28, 1856, at Staunton. Va., where his father, the Rev. Joseph Ruggles Wilson, was pastor of the Presbyterian Church. Not long after his birth the family moved to Augusta, Ga. Those who knew Woodrow Wilson well thought that he got his first stimulus to political thinking under the impressions of the reconstruction period.

He attended Princeton and entered the Law School of the University of Virginia and in 1882 he began to practice in Atlanta, but for law as a trade he appeared to have no aptitude. So he pursued a career in academia, eventually serving Princeton twelve years as professor and for eight more as President.

In his years as professor he wrote both books and magazine articles, and came into demand as a public speaker. He expressed a tenacious adherence to the idea that the place of the executive in the American Government was as the representative of the whole people, responsible for the advocacy before Congress of the greater policies, which could not be entrusted to a body whose members were concerned with local interests, nor to standing committees, impregnable to criticism and managed largely by log-rolling.

In the years leading up to 1912, the country at large was interested in him as a new and forceful representative of the popular political ideas, who was not handicapped by any accumulation of political enemies.

The public had seen him fight at Princeton with the “aristocracy” of the clubs, and with moneyed men on the Board of Trustees, and regarded the battles as a dramatization of the struggle against “special privilege,” which was then agitating the country.

In a sense, his entry into New Jersey politics was a sort of minor-league “try-out” which might fit him for fast company. Wilson, a Democrat, won the Governorship by 49,000 votes in a State which had usually been Republican in recent years.

Before the end of 1911 the Wilson-for-President movement was well under way all over the United States.

He won the nomination at Baltimore the next June. With the Republicans divided, the election went as was generally expected; Wilson was a minority President, to be sure, but he had a plurality of more than 2,000,000 over Roosevelt and nearly 3,000,000 over Taft, and he swept the electoral college with 435 votes to Roosevelt’s 88 and Taft’s 8. The election also gave the Democrats a heavy majority in Congress.

On March 4, 1913, he was inaugurated as President. He soon triumphed on the issues of tariff and currency reform, changes in anti-trust laws and the creation of the Federal Trade Commission.

The outbreak of the European war in August, 1914, seems to have surprised our Government. At the moment it seemed to call only for the formalities of a neutrality proclamation and a general tender of good offices for mediation toward peace.

While the President was criticized by those who were beginning to think that the war was our business, there was spreading among others the conviction that, whether it was our business or not, it might yet spread so far that we would become involved in it. And America was visibly unready for any war more formidable than an excursion into Mexico. The preparedness movement was countered by organized pacifist activities, with which almost from the first the pro-German faction allied itself.

The President treated the preparedness movement with disdain. He styled some of its advocates “nervous and excitable.”

There was now a growing prospect that even neutrality might not keep America from uncomfortable entanglements with the warring powers. This danger did not become acute, however, until the Germans on Feb. 4, 1915, declared British waters a war zone and announced the first submarine campaign. The American Government warned that if American vessels were sunk or American citizens killed, it would hold the German Government to “strict accountability.”

“Strict accountability,” however, had no terrors for the Germans. The submarines began to kill American citizens. With each new episode more Americans turned against the Germans, and the counter-activities of the pacifists and German agents increased.

Complaints against the failure to make the Germans check the submarines were increasing, chiefly in Republican papers, when the Lusitania was sunk on May 7, with the loss of more than 1,200 lives, including upward of a hundred Americans.

There was now a general feeling that something would be done. However, in a speech, the President invented another of the phrases which his opponents have constantly recalled.

“There is such a thing,” he said, “as a man being too proud to fight; there is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.”

Still, he sent a note to the German Government warning that the Administration would not “omit any word or act” necessary to defend the rights of Americans.

The country drew a long breath and prepared for whatever might happen. There was violent protest from the professional leaders of Irish and German racial groups and from the pacifists, but the mass of the articulate part of the population seemed ready for war if that must be.

The German answer was a series of evasions and exculpations. Meanwhile more American lives had been lost by the torpedoing of passenger ships, and the pressure of the American Government obtained from Germany on Sept. 1 a promise to torpedo no more passenger liners without warning. And for a time there were no more.

The partisan bitterness shown by pro-German elements in 1915 had been a revelation of unsuspected national disunity. In the weeks when war seemed an overnight possibility the President had contemplated the condition of the national defenses, and had seen that they were not adequate. He soon undertook a tour to stir up public interest in an improvement of military and naval defenses.

By 1916 Wilson was renominated at St. Louis by acclamation, and the platform gave his record full endorsement.

A significant episode in the convention was the keynote speech of Martin H. Glynn, built upon the theme. “He kept us out of war.”

Wilson went on to defeat Charles E. Hughes, with 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254, and a popular plurality of nearly 600,000.

The Democrats still held a majority of 12 in the Senate; in the lower house they had only 212 Representatives to 213 Republicans, with a corporal’s guard of scattering members holding the possibly decisive votes. But the President-Premier, leader of the party, had received a vote of confidence.

The President had been thinking about the proper terms for ending the war, and arrangements that might be made to remove the possibility of a similar catastrophe hereafter. The world was already talking of a League of Nations.

During all of 1916 the chief aim of the President’s foreign policy seemed to be to keep America in the position to play the leading part in a peace conference after the peace, and, if need be, take the initiative in bringing the belligerents to the peace table. The difficulty with the belligerents was that something was constantly happening to give one or the other side the hope of victory in a few months more. Moreover, the section of American opinion which favored the Allies was convinced that they must win in the end, and talk of mediation was suspected as being advantageous to Germany.

But the issue of peace or war had already been decided. On Jan. 9 the Germans resumed its policy of unlimited submarine warfare.

On Feb. 3, the President announced that he had broken diplomatic relations with Germany.

A note from Germany to Mexico, endeavoring to enlist Mexican and Japanese aid in the case of war with America, was intercepted by secret agents and published semi-officially. It convinced many who had hitherto been hard to persuade that war was near.

American merchantmen were attacked by submarines. After dissent in the Senate, the President armed the ships by executive order.

The country was waking up. Former pacifists and pro-Germans now stood firmly in support of the President’s policy. On April 2 the President appeared before Congress and asked for a declaration that the acts of the German Government constituted war against the United States. Neutrality was no longer possible, he declared.

“We have no quarrel with the German people,” he said, but their Government had shown itself to be “the natural foe of liberty.” So America would fight for the freedom of all peoples, the German people included; “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

It was the most famous of all his famous phrases. The logical dilemma had been solved; the President had found a new and transcendent issue.

Both houses passed the declaration of war by overwhelming majorities. A conscription bill went through Congress by a considerable majority.

The year ended with the allied cause in a rather bad way. The collapse of the Russian armies and the Bolshevist revolution had removed the eastern front. It was evident that the opening of 1918 would see bloodshed more copious than any previous year.

It was during this time, on Jan. 8, 1918, that Wilson gave an address to a joint session of Congress, embodying his Fourteen Points, which detailed his vision of a just peace, one that would allow the League of Nations to settle future conflicts peaceably.

In the Spring American soldiers began to go to France by the tens and hundreds of thousands, and by July 4 a million were on their way. By the end of Summer their intervention had turned the tide. German leaders now began to think of mediation by President Wilson.

In New York on Sept. 27, the President declared in a speech that the League of Nations must be a part of the peace settlement, “in a sense the most essential part.”

A new German Chancellor, Max of Baden, on Oct. 4 appealed to the President to call a conference at once. Step by step the Germans, their armies drawing nearer the old frontier every day, were driven to more concessions. On Oct. 12 they promised that the Fourteen Points would be accepted flatly. Two days later the President informed them that there must be an armistice whose terms would “assure the present supremacy” of the allied armies in the field.

On Nov. 5 the Allies informed the President that they accepted the Fourteen Points, with reservations. On Nov. 11 hostilities ceased.

President Wilson thus played the principal part in bringing the war to an end. It left him exalted in the opinion of Europe to a position such as no American ever before enjoyed. But he was not so generally exalted at home.

In the election of 1918, the country went Republican. Opponents of the Administration won a majority of 39 in the lower House, and a majority of two in the Senate, which would have to ratify the President’s treaty of peace.

A few days after the armistice was signed, when talk of the Peace Conference had begun, it was intimated in Washington that Lloyd George and Clemenceau wanted the President to come to the meeting. The sentiment of the American public, so far as could be judged from newspaper expression, was strongly against this. Nevertheless, the President decided to go.

He was leaving home after an election in which he had issued an unprecedented challenge and had been defeated. But he enjoyed a triumphal progress through Western Europe. Everywhere the masses of the people received him as the man who had given voice to their aspirations and led them out of the wilderness of war.

There was reason in this. The Fourteen Points and the other Wilson principles which had been accepted as a basis of peace were not so precise as to be incapable of varying interpretations.

Every nation in Europe believed that its program was founded on the principles of Wilson, and that Wilson had come to the peace conference to fight for precisely that.

The Peace Conference opened on the 18th of January. The history of its conflicts is too well known to need repetition. The European powers pressed their own ideas as to what the terms of surrender meant. Some American liberals, when the peace terms were eventually published, denounced the President for his “surrender to European imperialism.”

The Wilson who had been the world’s idol in December was now only the head of one of many States in conference. Every decision of Mr. Wilson in favor of any particular measure set a body of opinion against him.

Republican leaders at home blamed the President for the collapse of allied unity. Their opposition to the League of Nations, as President Wilson presented, also was growing. As early as Jan. 4, two weeks before the Conference met, Senator Lodge had said that the peace treaty ought to be first and the League discussion taken up later.

On the 14th of February the President read the text of the League covenant to the conference, which adopted it. A few days later the President started for home.

On the night of March 3 Senator Lodge announced that 37 Republican Senators were opposed to the acceptance of the League covenant in the form in which it stood.

Twenty-four hours later, at a meeting in New York, the President declared that the League was inextricably interwoven with the treaty and that he did not intend to bring the corpse of a treaty back from Paris. On the next day he sailed back to the Peace Conference.

The League covenant was somewhat modified to meet Republican suggestions and on June 28 the treaty was signed.

But he could not overcome opposition at home and the treaty was not ratified.

In the 1920 election, the Democratic nominee, Governor James M. Cox of Ohio, fought valiantly for the League, but was plainly willing to compromise on reservations that did not destroy the principles. Woodrow Wilson did not shift his position. But his health had suffered so much that he could not have taken part in the fight if he had wanted to.

The old scenes had changed. The Democratic Party of 1920 was not the party of 1912. Those who had fought in the front ranks in 1912 were most of them out of sight, and the final appeal to the country of the President-Premier for the ratification of a policy to which he had given four years of constant struggle was in the hands of an outsider, the Republican Warren G. Harding.

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES

March 8, 1841–March 6, 1935

WASHINGTON—Oliver Wendell Holmes, retired Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, where he served for 29 years, died this morning at his Washington home of bronchial pneumonia.

Death came at 2:15 o’clock to the great liberal of the Supreme Court and soldier of the Union, who would have been 94 years old Friday.

Since he retired on Jan. 12, 1932, Justice Holmes had spent nearly all of his days in his unostentatious little red brick house on I Street. There, in a mellow study running nearly from front to back of the dwelling, its walls lined with books, he read, dictated letters and received intimate friends.

He had waited for the end, his friends said, without fear or melancholy. When he left the bench he told his associates that “for such little time as may be left” he would treasure their friendship as “adding gold to the sunset.”

While he delved now and then into his law books, he loved a detective story or a tale with a humorous turn. He chuckled over the absurdities of P. G. Wodehouse’s starchy Englishmen. But he would turn now and then to a classic, with whose pages he was familiar years ago.

Although the culture that he gained from classic literature was always with him, he resorted often to quaint words and sentences, products, perhaps, of his New England upbringing. Most of his distinguished legal friends, one 65 years old, were known to him as just “young fellers.”

This was a symbol of the inherent democracy that led him to sit for hours and talk with a country flagman in the little railway station at Beverly Farms [in Massachusetts], where the justice spent many of his Summers. The flagman, incidentally, told a friend that the justice was the most unaffected man he ever knew.

He was such a stickler for the forms and ceremonies, for the dignity of the Supreme Court, that it was hard for those who did not know him to realize the great justice’s fresh, simple and amusing mental outlook. Despite all the reminiscences of his liberal findings in the court, his war exploits, his dignity, his personal charm, it is his sense of humor that seems to come first to the mind.

One authentic story concerns the play, “Of Thee I Sing,” with its flippancy toward the Supreme Court. It seems that in the scene where the court announces that the First Lady has borne a son, one character was to chant: “Brandeis and Holmes dissent.”

Eventually the line was deleted for fear of offending the aged justice, but when he heard of this he laughed heartily and said he wished that the sentence had been retained.

Mr. Holmes lived longer than any of the other 75 men who have sat upon the Supreme Court bench. He was the oldest man ever to have sat on the Supreme Court. Only eight justices served longer terms than his 29 years, among them John Marshall and Stephen J. Field, each of whom served 34 years.

As Justice Holmes grew old he became a figure for legend. Eager young students of history and the law made pilgrimages to Washington merely that they might remember at least the sight of him on the bench. Others so fortunate as to be invited to his home were apt to consider themselves thereafter as men set apart.

A group of leading jurists and liberals filled a volume of essays in praise of him, and on the occasion of its presentation Chief Justice [Charles] Hughes said: “The most beautiful and the rarest thing in the world is a complete human life, unmarred, unified by intelligent purpose and uninterrupted accomplishment, blessed by great talent employed in the worthiest activities, with a deserving fame never dimmed and always growing. Such a rarely beautiful life is that of Mr. Justice Holmes.”

He was born on March 8, 1841, in Boston. His father, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, was of New England’s ruling caste, and the atmosphere of his home was at once Brahminical, scientific and literary. The boy started each day at the breakfast table where a bright saying won a child a second helping of marmalade.

The boy was prepared for Harvard by E. S. Dixwell of Cambridge. Well-tutored, he made an excellent record in college. His intimacy with Mr. Dixwell’s household was very close. His tutor’s daughter, Fanny Dixwell, and he fell in love and later they were married. (She died in 1929.)

After Fort Sumter was fired on, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Holmes, 20 years old and shortly to be graduated from Harvard with the class of ’61, walked down Beacon Hill with an open Hobbes’s “Leviathan” in his hand and learned that he was commissioned in the 20th Massachusetts Volunteers.

The regiment was ordered South and into action at Ball’s Bluff in Virginia. There were grave tactical errors, and the Union troops were driven down the cliff on the Virginia shore and into the Potomac. Men trying to swim to safety were killed and wounded men drowned.

Lieutenant Holmes, with a bullet through his breast, was placed in a boat with dying men and ferried through saving darkness to the Maryland shore. For convalescence he was returned to Boston. On his recovery he returned to the front.

At Antietam a bullet pierced his neck and again his condition was critical. Dr. Holmes, on learning the news, set out to search for his son. He found him already convalescent and brought him back to Boston.

Back at the front, the young officer was again wounded. A bullet cut through tendons and lodged in his heel. This wound was long in healing and Holmes was retired to Boston with the brevet ranks of Colonel and Major.

The emergency of war over, his life was his own again. He finally turned to law, although it was long before he was sure that he had taken the best course.

“It cost me some years of doubt and unhappiness,” he said later, “before I could say to myself: ‘The law is part of the universe—if the universe can be thought about, one part must reveal it as much as another to one who can see that part. It is only a question if you have the eyes.’”

Philosophy and William James helped him find his legal eyes while he studied in Harvard Law School and James, a year younger, was studying medicine. But while James went on, continuing in Germany his search for the meanings of the universe, Holmes decided that “maybe the universe is too great a swell to have a meaning,” that his task was to “make his own universe livable.”

He took his LL.B. in 1866 and went to Europe to climb some mountains. Early in 1867 he was admitted to the bar. In 1870 he was made editor of the American Law Review.

Two years later, on June 17, 1872, he married Fanny Bowditch Dixwell and in March of the next year became a member of the law firm of Shattuck, Homes & Munroe. In that same year, 1873, his important edition of Kent’s Commentaries appeared.

His papers, particularly one on English equity, which bristled with citations in Latin and German, showed that he was a master scholar. It was into these early papers that he put the fundamentals of an exposition of the law that he was later to deliver in lectures at Harvard and to publish under the title, “The Common Law.” In this book, to quote Benjamin N. Cardozo, he “packed a whole philosophy of legal method into a fragment of a paragraph.”

The part to which Judge Cardozo referred reads: “The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy avowed or unconscious, even with the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men, have had a great deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.”

Holmes was only 39 years old when Harvard called him back to teach in her Law School, and 41 when he became an Associate Justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Court bench. He was Chief Justice on the Commonwealth bench when, in 1901, Theodore Roosevelt noted that Holmes’s “labor decisions” were criticized by “some of the big railroad men and other members of large corporations.”

For Roosevelt, that was “a strong point in Judge Holmes’s favor.” In 1902, President Roosevelt appointed Judge Holmes to the Supreme Court of the United States, an appointment that was confirmed by the Senate immediately and unanimously.

A great struggle between the forces of Roosevelt and the elder J. P. Morgan began on March 10, 1902, when the government filed suit in Federal Court charging that the Great Northern Securities Company was “a virtual consolidation of two competing transcontinental lines,” whereby not only would “monopoly of the interstate and foreign commerce, formerly carried on by them as competitors, be created,” but, through use of the same machinery, “the entire railway systems of the country may be absorbed, merged, and consolidated.”

In April, 1903, the lower court decided for the government and the case went to the Supreme Court. On March 14, 1904, the High Court found for the government, with Justice Holmes writing in dissent.

He held that the Sherman act did not prescribe the rule of “free competition among those engaged in interstate commerce,” as the majority held. It merely forbade “restraint of trade or commerce.” He asserted that the phrases “restraint of competition” and “restraint of trade” did not have the same meaning; that “restraint of trade,” which had “a definite and well-established significance in the common law, means and had always been understood to mean, a combination made by men engaged in a certain business for the purpose of keeping other men out of that business.”

The objection to trusts was not the union of former competitors, but the sinister power exercised by the combination in keeping rivals out of the business, he said. It was the ferocious extreme of competition with others, not the cessation of competition among the partners, which was the evil feared.

“Much trouble,” he continued, “is made by substituting other phrases, assumed to be equivalent, which are then argued from as if they were in the act.”

From the opinions and other writings of Justice Holmes the following lines are some that stand out: “The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.… That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment.”

Soon after he resigned on Jan. 12, 1932, he sent a message to the Federal Bar Association: “I cannot say farewell to life and you in formal words. Life seems to me like a Japanese picture which our imagination does not allow to end with the margin. We aim at the infinite, and when our arrow falls to earth it is in flames.”

LOUIS BRANDEIS

November 13, 1856–October 5, 1941

WASHINGTON—Louis Dembitz Brandeis, retired Associate Justice of the Supreme Court and one of the greatest liberals in the history of that tribunal, died at his residence here at 7:15 o’clock this evening.

Justice Brandeis, whose name was often linked in dissents with that of the late Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, would have been 85 years old on Nov. 13. He had a heart attack on Wednesday and had been in a coma before the end. At his bedside were Mrs. Brandeis and their two daughters. Mrs. Brandeis received from President Roosevelt a message of condolence.

In frail health during the last two years, he devoted himself largely to consideration of the problems of Jews, whose plight during the European war and under the Nazi persecutions affected him intensely.

More than 82 years old at the time of his retirement, Justice Brandeis was nevertheless marked for his logic, surprising intellectual energy, and extraordinary ability to obtain the basic facts in legal controversies. But his physical strength was decreasing, and after a siege of grippe in January, 1939, he decided to leave the bench where he had sat so long.

When Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes died, in 1935, the mantle of judicial liberalism long since had been wrapped about the lean shoulders of Louis Dembitz Brandeis, like his mentor an outstanding apostle of dissent. He already had spent a long lifetime in pursuit of justice, both real and in the abstract, before he was appointed to the highest court of the land by Woodrow Wilson in 1916.

Throughout the years that followed he continued to pursue it, handing down decision after decision that sparkled with the integrity of his mind, the breadth of his learning and great human qualities which the exactitudes of legalism were never able to dull.

He had been appointed against the wishes of a united front which used every weapon at its command to keep him from donning the black silken robes of an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. But when, ten years after he had passed man’s allotted span, his aquiline face still peered down from the august bench, men and women in every walk of life, including some of his most bitter former enemies, joined in paying him tribute as one of America’s best-loved citizens.

In one of his best-known dissenting opinions, Justice Brandeis expressed those qualities which endeared him even to those who, spurred on by President Roosevelt in 1937, felt that an age limit of 70 years should be imposed upon the members of the Court. He read this decision in a quiet, almost colorless voice on March 21, 1932, while Herbert Hoover was still President and the New Deal had not been broached.

“Some say that our present plight is due, in large measure, to the discouragement to which social and economic invention has been subjected,” he said. “I cannot believe that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, or the States which ratified it, intended to leave us helpless to correct the evils of technological unemployment and excess productive capacity which the march of invention and discovery have entailed. There must be power in the States and the nation to remold through experimentation our economic practices to meet changing social and economic needs.

“To stay experimentation within the law in things social and economic is a grave responsibility. Denial of the right to such experimentation may be fraught with serious consequences to the nation. It is one of the happy incidences of the Federal system that a single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country. This court has the power to stay such experimentation. We may strike down the statute embodying it on the ground that, in our opinion, it is arbitrary, capricious or unreasonable; for the due-process clause has been held applicable to substantive law as well as to matters of procedure. But in the exercise of this power we should be ever on guard, lest we erect our prejudices into legal principles.

“If we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold.”

Behind these words lay three-quarters of a century in which Justice Louis Brandeis had steadfastly endeavored to guide by the light of reason and in which he had been characterized by the boldness of his mind.

Justice Brandeis arbitrated the 1910 garment strike in New York, which affected 70,000 workers and $180,000,000 worth of business; he drove Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger from office in the Indian “land-grab” scandals of the Taft administration, and he fought zealously the battle of the small entrepreneur, summarizing his economic philosophy in the famous phrase, “the curse of bigness.”

It was said of the Justice that he matured early and never had a chance to change his mind about the fundamentals. In 1905 he said: “Democracy is only possible—industrial democracy—among people who think… and that thinking is not a heaven-born thing. It is a gift men make and women make for themselves. It is earned, and it is earned by effort.”