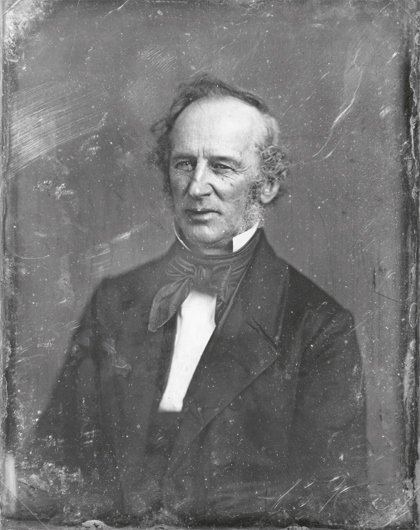

CORNELIUS VANDERBILT

May 27, 1794–January 4, 1877

Commodore Vanderbilt died at his residence, No. 10 Washington place, yesterday morning, after having been confined to his rooms for about eight months. The immediate cause of his death was exhaustion, brought on by long suffering from a complication of chronic disorders.

Shortly after daylight his family were summoned to his bedside to bid him farewell. He was too weak to say much, but expressed much gratification at having them around him, and after they had been with him a short time requested them to join in singing his favorite hymns. Prayer was then offered, in which he tried to join, and shortly afterward, gradually becoming weaker and weaker, he quietly passed away without a struggle. His death, which had been long expected in financial circles, had little or no effect on the stock market, although the announcement of it created a decided impression throughout the City.

It is estimated that Commodore Vanderbilt left property to the amount of $100,000,000, principally in shares of the New-York Central and Hudson River Road and other railway corporations; but, although it is known that he left a will, it is not known how he has disposed of his wealth. The funeral services will take place at the Church of the Strangers on Sunday at 10:30 A.M., and the remains will then be carried to Staten Island and deposited in the family vault in the Moravian churchyard, near New Dorp.

Cornelius Vanderbilt was born on the 27th day of May, in the year 1794, on a farm on Staten Island. His father was a well-to-do agriculturist. The produce of the farm was sent to the New York markets in a periagua daily, and the young Cornelius took especial delight in navigating this craft, which has now disappeared from our waters. He worked also on the farm, and studied in the Winter days, but his delight was on the sea, and while he was a mere boy he was acknowledged to be the most fearless sailor and the steadiest helmsman on the bay. All his thoughts and instincts were bent in that direction. His one dream was of having a periagua of his own, and sailing it as a ferry-boat between Staten Island and New York. In 1810 he persuaded his mother to give him $100 for the purchase of a boat, and his hand closed firmly upon the tiller which for the next half century was to be to him a veritable scepter.

He was but sixteen, but he had no difficulty in obtaining passengers for his ferry-boat. For the young man was tall, vigorous, broad of shoulder, bright of eye, possessed of a complexion that any belle might envy, and having a very sweet and engaging smile, which all the cares of a very extraordinary and busy life never effaced from his countenance. There was plenty of occupation for him, for the times favored his business. England, plunged in the Napoleonic war, was furious with the services which America, as a neutral State, was able to perform for the French Emperor, and it was obvious that a war must sooner or later settle the power of a neutral flag to protect a cargo. Forts were built on different parts of the bay and on Staten Island, and in the transportation of material Cornelius Vanderbilt was so fair and moderate in his pretensions as to obtain the greater share of the business.

Young Cornele, as everybody called him, was the first person thought of when anything very dangerous or very disagreeable had to be done. When the winds were high, and the sight was blinded with driving sleet and snow, and the waves raged like angry wolves, if an important message had to be sent from the forts to the headquarters in the City, young Cornele was sent for.

In this carrying business he was so successful and made so much money that he thought of starting a home for himself. He married, in December, 1813, Miss Sophia Johnson, of Port Richmond, Staten Island, and expanded his transactions, as if the consciousness that he had given hostages to fortune in the shape of a young, beloved wife had spurred him to increased boldness. Between ship-building and ship-owning, when he balanced his books on the 31st December, 1817, being then twenty-three years and six months old, he found himself the master of $9,000 in hard cash.

Had Cornelius Vanderbilt been an ordinary thinker he would have gone on in this path. He would have sailed and built and chartered vessels and have made a great fortune. But he was an extraordinary thinker, and even in the midst of his young flush of triumph in naval construction there was one thing that troubled him. This was steam.

Fulton was beginning to sail his first regular boat up the Hudson, and some applauded and some derided the invention. The shipping men, as a class, pooh-poohed the whole thing, and very plausibly showed that in consequence of the cumbrous machinery and bulk of fuel, the new invention could not possibly he utilized for carrying freight, which was perfectly true at that time.

But as young Vanderbilt reasoned the thing out in his own mind, he came to the conclusion that the future belonged to the steam-boats. So he renounced the coasting business, sold his interest in different vessels, and built so many magnificent steamers that the public christened him the Commodore, just as the soldiers of the First Napoleon had nicknamed him the Little Corporal. His boats were faster and better, they were more comfortable for passengers, and more commodious for freight than any which had hitherto been seen.

The war of the slaveholders’ rebellion brought the Commodore as a chosen counselor to the President of the nation. The Merrimac iron ram of the Confederates had wrought such havoc with the Union fleet as filled loyal men’s hearts with gloom. Naval men were unanimous upon the point that if the ram could be fought and smashed there was but one man that could do it, and his name was Cornelius Vanderbilt.

To this man came a telegram asking for his presence in Washington. He came to the house of the Secretary of War, and was greeted with enthusiasm. “Will you,” said Stanton, “see the President?” “Certainly,” was the reply, and to the President’s presence the pair went. “Now,” said Mr. Lincoln, “can you stop that rebel ram, and for how much money will you do it?”

The Commodore answered, “I think I can, Mr. President, but I won’t do it for money. I do not want the people of this country to look upon me as one who would trade upon her necessities and make blood-money out of her wounds.”

Mr. Lincoln shook his head, and evidently thought that the Commodore was a Confederate sympathizer, for he said: “What’s the use of further talking! You won’t do anything for us, I see.”

Vanderbilt said: “I don’t know about that, Mr. President. I place myself and all my resources at your disposition without pay.” Joyfully the patriotic proposal was accepted, and in 36 hours the Vanderbilt, with the Commodore in command, was at its station in Hampton Roads.

His reputation as a skillful pilot was known to everyone, and when he said that he would run down the Merrimac as a hound runs down a wolf, and, striking her amidships, would send her to the bottom, they all believed that he would do it, and looked admiringly at his huge steamer, the shadow of whose black hull loomed upon the water like the reflection of a great cloud.

“How can we help you?” said the chief officer. “Only by keeping severely out of my way when I am hunting the critter,” was the amusing response, at which every one laughed. But the coursing match never came off. The Merrimac’s Captain, who had been in Vanderbilt’s employ, and knew his antagonist, declined to come out from his hiding place. Nor did the Confederates dare again to send her up the Roads.

Well before the exigencies of war sought him out, Commodore Vanderbilt had turned his tireless brain to consider the inevitable decline of American shipping, and to discover what form of enterprise was the most capable of development. At the war’s end, he was nearly 71 years of age, but hale and hearty as a youngster of 20. The world accepted him as the greatest steam-boat man that ever lived, but they did not comprehend that he was great at everything, not to be judged by ordinary rules or average mental measuring rods.

And so he turned his attention to railroads, swiftly buying up the Hudson River and Harlem roads in New York, dismissing incapable and dishonest officers, introducing reforms, and in an incredibly short time making these roads a paying institution, a sound investment security. In 1867 the leading shareholders of the competing New-York Central appealed to the Commodore to “select such a Board of Directors as shall seem to you to be entitled to their confidence.”

Now began a series of improvements in the railroad system of the City of New York which fairly transformed it. Commencing with the consolidation of the Hudson River and Central, and the leasing of the long line of the Harlem, Mr. Vanderbilt projected the building of the Forty-second Street Depot, and in due order followed the introduction of steel rails, the laying of a quadruple track from one end of the line to the other, and the wonderful engineering feat of sinking the City part of the track and arching it over for the prevention of accidents, and the improvement of that fine district along Fourth Avenue. The speed of the trains was so greatly increased that to go from New York to Albany in four hours became a common occurrence, yet the distance is fully 150 miles.

In his private life the Commodore was always distinguished by three things—overwhelming affection for his family and his friends, hatred of ostentation, and love of solid comfort. He had lived for many years past in a great double brick house on Washington Place, handsomely furnished, but without the least pretension.

His first wife died in the early part of 1868, which left the Commodore alone in his big house, for all his ten surviving children were married, and some of them had grandchildren even. So in the Fall of 1869 the house on Washington Place received a new mistress, a very handsome and accomplished Southern lady, from Mobile, Ala., formerly a Miss Crawford. The master of the house was all his life surrounded by friends who repaid his affection by a love “this side idolatry,” as Ben Jonson said of Shakespeare. Iron in opposition, he was in private life entirely governed by his affections, nor did age take from him the sweet smiling look of his boyhood.

The eldest son, William H. Vanderbilt, will perhaps take his father’s place as a railroad man. He is as much master of the facts of every department as the chief of it, and he is a model of hard-working industry. No man possesses the technique of railroad management in as full a measure as he, and he is training up his sons in the same path.

So the Vanderbilt lines will probably be managed by Vanderbilt scions for generations to come, to the great content of all interested. It is a fair prophecy that the line will not lose one cent by the death of Cornelius Vanderbilt, for the system which he created will live long after him. And herein was displayed another proof of the transcendent powers of his genius, since he so vitalized the Vanderbilt lines and infused such energy into them that they will retain the effects for 50 years to come.

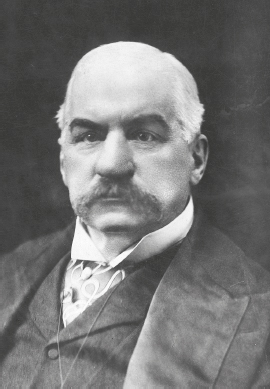

J. PIERPONT MORGAN

April 17, 1837–March 31, 1913

ROME—J. Pierpont Morgan died at the Grand Hotel here five minutes after noon today.

His last words were addressed to his son-in-law, Mr. Herbert Satterlee, to whom he said, “You bet I will pull through.”

J. Pierpont Morgan had been the leading figure in American finance for almost as long as the present generation could remember and was often described as the biggest single factor in the banking business of the world. The story of his life is indissolubly intertwined with the periods of expansion in this country in the world of railroads, industrial organization, and banking power.

The pinnacle of his power was reached in the panic of 1907 when he was more than 70 years old. He was put at the head of the forces that were gathered together to save the country from financial disaster, and men like John D. Rockefeller and E. H. Harriman put themselves and their resources at his disposal. Secretary of the Treasury [George B.] Cortelyou, coming to New York to deposit Government funds to help support the tottering financial structure, recognized Mr. Morgan’s leadership and acted on his advice in every particular.

Unlike many of the men of great wealth in this country. Mr. Morgan, who was born in Hartford on April 17, 1837, did not have the incentive of poverty to spur him on. He was heir to a fortune estimated at $5,000,000 to $10,000,000.

The decade from 1880 to 1890 was characterized by the most extensive and destructive competition between the railroad systems of the country, and it was during this period that J. P. Morgan developed the policy regarding railroad affairs that he stood forever after. It found its concrete expression in the famous West Shore deal in 1885, which ended a period of warfare almost without parallel between the New York Central and the West Shore Railroad.

At the opening of the new century Mr. Morgan was the largest financial figure on this side of the water, if not in the world. He had gathered around him a notable group of men, including George F. Baker, President of the First National Bank, with which Morgan had more intimate relations than with any other institution.

Big things began to happen with the opening of 1901, and J. P. Morgan was the biggest figure in the doing of them. In January it was announced that he had bought the Jersey Central Railroad and turned it over, with its valuable coal properties, to the Reading. Soon came word that the Pennsylvania Coal Company, the Hillside Coal Company, and others had been bought and turned over to the Erie, two acquisitions which brought the control of the anthracite traffic practically within the Morgan sphere of influence.

Then came news that Andrew Carnegie was going to start a steel plant at Conneaut, Ohio, to manufacture “merchant pipe” in competition with Mr. Morgan’s Federal Steel Company and John W. Gates’s American Steel and Wire Company.

Here was a denial of the principle which Mr. Morgan had worked for in the railroad field for 20 years. The Steel Corporation was launched in February to take over the Carnegie Steel Company, the Federal Steel, the American Steel and Wire, the American Tin Plate, the American Steel Hoop, and the American Sheet Steel.

This United States Steel enterprise was as notable an example of J. P. Morgan’s optimism as anything in his life. It was capitalized on the expectation that the conditions of the most prosperous year in the country’s history would continue indefinitely. When the depression of 1903 came along, and the steel stocks dropped off, a banker asked Mr. Morgan what he thought about it.

“I am not concerned with the stock market conditions of the Steel stocks” was the gruff reply, “but I can tell you that the possibilities of the steel business are just as great as they ever were.”

When the first rumblings were heard of the storm that would become the furious panic of October, 1907, Mr. Morgan was regarded by many as already out of active life. He was 70 years old and when in this country spent most of his time at his home and library uptown, while J. P. Morgan, Jr., and the other partners in the firm carried on its business.

“Morgan is out of it” was a common view in Wall Street. “He is old and tired and his reputation has suffered. We must look elsewhere for leadership.”

How erroneous these ideas were it took but a few weeks to show. While nearly all the captains of finance in Wall Street were lying awake nights in the Spring of 1907, wondering how much longer they could stand the strain, Mr. Morgan was in Europe paying fabulous prices for works of art.

In March came the first signs of panic in the stock market. Worldwide financial disturbance followed a phenomenal break on the New York Stock Exchange. The decline continued until, on March 14, there was a terrific collapse, to be followed by the October panic, caused by the collapse of F. Augustus Heinze’s pool in United Copper shares.

Mr. Morgan had been quietly studying the situation. He sat at his desk nearly every day and listened to reports, but said nothing. He was still studying the situation when the panic came.

The National Bank of Commerce, one of the chief Morgan banks, gave notice that after Oct. 22 it would no longer clear checks for the Knickerbocker Trust Company. On the night of Oct. 21 the leading bankers held a conference with Mr. Morgan at his house, and it was reported that he had refused to extend any aid to the trust companies that were on the ragged edge.

The next day the Knickerbocker Trust closed, after paying out $8,000,000 to depositors. That night there was another conference over the affairs of the Trust Company of America, and the next morning a run on that institution started.

Secretary of the Treasury Cortelyou was sent to New York to help afford relief to the banking situation. On Oct. 23 Mr. Morgan and other bankers met Secretary Cortelyou at the Manhattan Hotel, and the Secretary agreed to add $25,000,000 to the Government’s deposits.

Again the situation pointed to Mr. Morgan as the only possible leader. Government funds could be deposited only in National banks, not trust companies, and in any case, Mr. Cortelyou explained, he could not give relief to individual banks but had to deal with the situation as a whole. One man who could superintend the whole field was needed, and Mr. Morgan was the man.

When he entered his office the next morning his power was absolute. He was the arbiter between the banks, the trust companies and the National Treasury. His was the power to say who should and should not borrow money. Stock speculation was brought to an end by his fiat. In the days that followed John D. Rockefeller came to him with an offer of $10,000,000 in bonds to be used in securing Government deposits for the afflicted banks. His office was crowded with men like E. H. Gary, head of the Steel Corporation, with $75,000,000 in cash, and James Stillman, representing the untold millions of Standard Oil.

On that first day, with Mr. Morgan fully in the saddle, the Hamilton Bank and the Twelfth Ward Bank closed. The run on the Trust Company of America went on. The streets in the financial district were filled with frenzied throngs. All that day Mr. Morgan sat at his desk, listening to reports, which he received with short, gruff comments.

On the next day, Oct. 24, a run started in the Lincoln Trust Company, and behind this and the Trust Company of America Mr. Morgan determined to make his stand. As securities were thrown into the vortex of the Stock Exchange by frightened investors and by banking institutions that had to liquidate their holdings to meet the demands of the money-hungry lines before their doors, call money on the Exchange soared to incredible heights. Finally no money was to be had at any price.

In the afternoon, R. H. Thomas, President of the Exchange, went to President Stillman of the National City Bank and told him that $25,000,000 was needed to prevent the closing of the Exchange. What followed was recounted by Mr. Thomas:

“Mr. Stillman replied, ‘Go right over and tell Mr. Morgan about it.’ I went to the office of J. P. Morgan & Co. The place was filled with an excited crowd. After a time Mr. Morgan came out from his private office and said to me, ‘I’m going to let you have $25,000,000. Go over to the Exchange and announce it.’”

The next day some of the smaller banks closed while the run on the two trust companies kept up. Another money pool of $10,000,000 was made up in Morgan’s office. By the end of the week the Government deposits amounted to $32,000,000.

Conferences were held at Mr. Morgan’s house on Sunday, Nov. 3, and at the Waldorf, some of them lasting till 5 in the morning. Plans were made for saving the Lincoln Trust and the Trust Company of America.

That the panic immediately ended is a matter of history.

J. P. Morgan was married twice. His first wife was Amelia Sturges, who died in 1862. In 1865 he married Frances Louise Tracy, who survives him. They had four children, all of whom survive him.

The town house of J. P. Morgan, at Madison Avenue and 36th Street, is notable because of the attractive gardens lying between it and that of J. P. Morgan, Jr., at 37th Street. Including the Morgan building, which houses the Morgan private library and art treasures, this is one of the most attractive groupings of private residences in the heart of the city.

The favorite Summer home of Mr. Morgan was his estate, Cragston, at Highland Falls [N.Y.]. Whenever Mr. or Mrs. Morgan sailed abroad, hampers of the things produced there were sent to the ship. On their trips from here to Cragston the Morgans usually traveled on the Morgan yacht, the Corsair.

Mr. Morgan’s youngest child, Miss Anne T. Morgan, helped establish a restaurant for workers in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which sought to provide them with good and moderate-priced food.

Frequently reports have had it that Miss Morgan was to marry. To a friend Miss Morgan said: “I have not yet met a man whose wife I’d rather be than the daughter of J. Pierpont Morgan.”

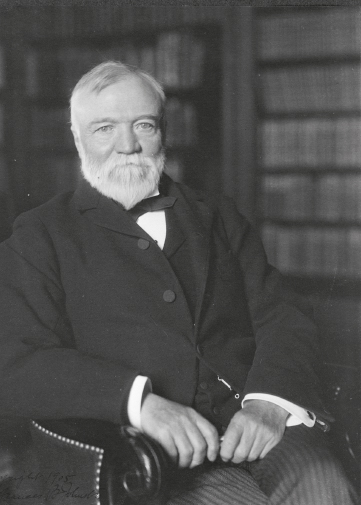

ANDREW CARNEGIE

November 25, 1835–August 11, 1919

LENOX, Mass.—Andrew Carnegie died at Shadow Brook of bronchial pneumonia at 7:10 o’clock this morning.

Mr. Carnegie was about his estate, apparently in his usual health, on Friday morning with Mrs. Carnegie and his daughter, Mrs. Roswell Miller. Friday evening he complained of difficulty in breathing, but seemed to have nothing worse than a cold.

On Saturday morning he felt fairly well and walked about his home, but during the day he seemed to grow weaker. He grew rapidly worse through Sunday. Mr. Carnegie was in his 84th year.

Of recent days the old man, who was a great lover of flowers, had been fond of being wheeled in a chair into his garden, where he passed many hours. He always wore in the buttonhole of his homespun sack suit a sprig of sweet verbena, which was his favorite plant.

Andrew Carnegie was born Nov. 23, 1835, in Dunfermline, a little manufacturing town in Fifeshire, Scotland, at that time noted for its weaving. His father and his ancestors for a long way back had been weavers, and at the time of Andrew’s birth the elder Carnegie owned three or four hand looms, one of which he operated himself. Andrew was to have been a weaver, too, but new inventions were soon to abolish the industry, and William Carnegie, his father, was the last of the weaving line.

Andrew earned his first penny by reciting Burns’s long poem, “Man Was Made to Mourn,” without a break. There is a story that in Sunday school, being called upon to recite Scripture text, he astonished the assembly by giving this: “Look after the pence, and the pounds will take care of themselves.”

Estimates of Mr. Carnegie’s wealth made yesterday put it at possibly $500,000,000. When he retired in 1901 he sold his securities of the Carnegie Steel Company to the United States Steel Corporation for $303,450,000 in bonds of that company. He was possessed of large interests in addition to those bonds. When he started in 1901 to endow his great benefactions, he made inroads into his capital for several years in gifts to libraries for peace propaganda, and to other philanthropic causes.

The fortune of $303,450,000 in 5 percent bonds, if allowed to increase by the accumulation of interest and reinvestment since 1901, would amount to about a billion dollars today, but his numerous benefactions prevented this. According to financial authorities, however, the ironmaster’s ambition to die poor was not realized, and, despite the scale of his philanthropies, it was believed that his fortune was at his death as large as it ever was.

When he was 12 years old the steam looms drove his father, the master weaver, out of business, and, reduced to poverty, the family emigrated to America. There were four, the parents and two boys, Andrew and Thomas. They settled at Allegheny City, Penn., across the river from Pittsburgh, in 1848. The father and Andrew found work in a cotton factory, the son as bobbin boy. His pay was $1.20 in this, his first job. He was soon promoted to be engineer’s assistant, and he stoked the boilers and ran the engine in the factory cellar for 12 hours a day.

It was at this time, he afterward said, that the inspiration came for his subsequent library benefactions. Colonel Anderson, a gentleman with a library of about 400 books, opened it to the boys every weekend and let them borrow any book they wanted. “Only he who has longed as I did for Saturdays to come,” he said, “can understand what Colonel Anderson did for me and the boys of Allegheny. Is it any wonder that I resolved if ever surplus wealth came to me, I would use it imitating my benefactor?”

At 14, he became a telegraph messenger and soon learned telegraphy. It was the first step upward. “My entrance into the telegraph office,” said Carnegie, “was a transition from darkness to light—from firing a small engine in a dark and dirty cellar into a clean office with bright windows and a literary atmosphere, with books, newspapers, pens, and pencils all around me. I was the happiest boy alive.”

He became an operator. When the Pennsylvania Railroad put up a telegraph wire of its own, he became clerk under Divisional Superintendent Thomas A. Scott. At that time telegraphy was still new. The dots and dashes were not read by sound, but were all impressed on tape, and Carnegie is said to have been the third operator in the United States to read messages by sound alone. Scott told the President of the road that he “had a little Scotch devil in his office who would run the whole road if they’d only give him a chance.”

Colonel Scott became General Superintendent of the Pennsylvania in 1858 and Vice President in 1860, taking Carnegie along with him at each rise. In May, 1861, the Civil War had broken out and Scott was appointed Assistant Secretary of War in charge of military railroads and telegraphs, and again he took Carnegie with him. Carnegie was now Superintendent of the Western division of the road, and did not want to go to Washington, but Scott insisted.

Mr. Carnegie was placed in charge of the Government telegraph communications. He went to Annapolis and opened communications which the Confederates had interrupted. He started out on the first locomotive which ran from Annapolis to Washington. While passing Elbridge Junction he noticed that the wires had been pegged down by the enemy. He stopped the engine, jumped down beside the wires, and cut them. One of them sprang up and gave him a wound in the cheek, the scar of which remained with him all through life.

Soon, he began to lay the foundation of his wealth. He gained an interest in a small company that made the first sleeping cars and made a profit of about $200,000. He put $40,000 in a company formed for the development of an untried piece of oil land. The company struck oil, and the share remaining to him was worth a quarter of a million.

He invested in iron works in 1863 and two years later became part of a combination called the Union Iron Mills.

It was just at the right time. The Civil War had just ended and the great expansion was beginning. The new concern made great profits, and Carnegie proposed further ventures. It was the era of the building of railroads and the development of the West. Steel rails had become worth $80 to $100 a ton.

By this time Andrew Carnegie was recognized as the leader of this Napoleonic combination, which, with every new success, reached out further. He introduced the Bessemer steel process, which had been a success in England, in his own mills and became principal owner of the Homestead and Edgar Thomson Steel Works and other large plants as head of the firms of Carnegie, Phipps & Co. and Carnegie Brothers & Co.

In 1899 the interests were consolidated in the Carnegie Steel Company, which in 1901 was merged in the United States Steel Corporation, when Mr. Carnegie retired from business.

In 1888 he married Louise Whitefield, who was 20 years his junior. They had one child, Margaret, born in 1897. Mr. and Mrs. Carnegie spent their honeymoon on the Isle of Wight, and then they went to Scotland, where they leased a castle and occupied it for ten years. In 1897, the year of Margaret’s birth, Mr. Carnegie bought Skibo Castle [in Scotland], and since then it has been their regular Summer home from May to October. Mrs. Carnegie’s chief philanthropic interest has been to work among the thousand-odd tenants of the estate.

The only great clash with labor which occurred while Mr. Carnegie was in business was the Homestead strike of 1892. He was in Europe at the time, and came in for much criticism for not returning and for letting the trouble go to a finish without any action by him.

He sold out to the Steel Corporation for $420,000,000, and in his testimony before the Stanley Committee in 1912, referring to this bargain, he exclaimed, “What a fool I was! I have since learned from the inside that we could have received $100,000,000 more from Mr. Morgan if we had placed that value on our property.”

His famous utterance about “dying disgraced” appeared in an article in the North American Review in 1898, in which he said:

“The day is not far distant when the man who dies leaving behind him millions of available wealth, which were free for him to administer during life, will pass away ‘unwept, unhonored, and unsung,’ no matter to what use he leaves the dross which he cannot take with him. Of such as these the public verdict will be, ‘The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.’”

In 1907 he was the central figure of the dedication of the Carnegie Institute at Pittsburgh, which had cost him $6,000,000.

In “Problems of Today,” a book published in 1907, Mr. Carnegie expressed some views on wealth which are unusual in a millionaire. He declared socialism, viewed upon its financial side, to be just, and said, “A heavy progressive tax upon wealth at death of owner is not only desirable, it is strictly just.”

Mr. Carnegie did not believe in alms-giving. His idea was to help others help themselves, which was why he said, of his gifts of organs to churches, “I now only give one-half the cost, the congregations first provide the other.” As for beggars, he was proud of his indifference to them: “I never give a cent to a beggar, nor do I help people of whose record I am ignorant; this at least is one of my really good actions.”

He conceived the original idea of forming a corporation for the purpose of paying out money. It was the Home Trust Company, and it was simply his disbursing office. Its headquarters were in New York.

What is believed to have been one of the last letters written by Mr. Carnegie, in which he expressed his gratification at the proposed League of Nations, was made public here yesterday by Charles C. James, a broker, to whom the communication was addressed.

“I rejoice in having lived to see the day,” said Mr. Carnegie’s letter, “when, as Burns puts it, ‘man to man the world o’er shall brothers be and a’ that.’ I believe this happy condition is assured by the League of Nations and that civilization will now march steadily onward, with no more great wars to mar its progress.”

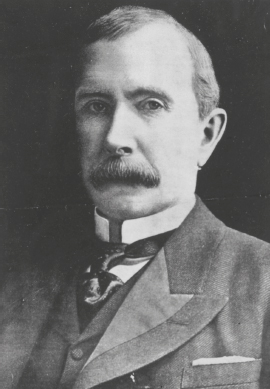

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER

July 8, 1839–May 23, 1937

By Paul Crowell

ORMOND BEACH—John D. Rockefeller Sr., who wanted to live until July 9, 1939, when he would have rounded out a century of life, died at 4:05 A.M. here today at The Casements, his Winter home, a little more than two years from his cherished goal.

Death came suddenly to the founder of the great Standard Oil organization. Less than 24 hours before the aged philanthropist died in his sleep, his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., had been assured that nothing about his father’s condition should cause concern.

John Davison Rockefeller was the richest man in the world at the height of his active career. Starting his business life as a poor boy in an office, with little formal education and no capital, he became the pioneer of efficient business organization and the modern corporation, the most powerful capitalist of his age, and the greatest philanthropist and patron of higher education, scientific research and public health in history.

It was estimated after Mr. Rockefeller retired from business that he had accumulated close to $1,500,000,000 out of the earnings of the Standard Oil trust and other investments, probably the greatest amount any private citizen ever accumulated by his own efforts.

His 1918 income tax returns indicated that his taxable income was then $33,000,000 and his total fortune probably more than $800,000,000.

Mr. Rockefeller, who had been the greatest “getter” of money in the country during the years he was exploiting its oil resources, became, after his retirement, the world’s greatest giver. He gave even more than Andrew Carnegie, whose philanthropies amounted to $350,000,000.

Not until Mr. Rockefeller’s death was it disclosed that between 1855 and 1934 he had made gifts to charitable and educational organizations totaling $530,853,632.

Of this sum, $182,851,480 went to the Rockefeller Foundation, $129,209,167 to the General Education Board, $73,985,313 to the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial in New York City and $59,931,891 to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research.

The life story of the man who started with nothing and accumulated and gave away so much is the outstanding example of the romance of American business.

He was born in Richford, a village in Tioga County, near Oswego, N.Y., on July 8, 1839. His father was William Avery Rockefeller, a country doctor and farmer. His mother was Eliza Davison. He had two brothers.

The story of his first business experience is told in “Random Reminiscences of Men and Events,” the only book Mr. Rockefeller ever published.

“When I was 7 or 8 years old,” he wrote, “I engaged in my first business enterprise with the assistance of my mother. I owned some turkeys, and she presented me with the curds from the milk to feed them. I took care of the birds myself and sold them all in businesslike fashion. My receipts were all profits, as I had nothing to do with the expense account, and my receipts were kept as carefully as I knew how.”

The great gifts Mr. Rockefeller made to charity and his active interest in the church can also be traced to the lessons he learned early on. His parents taught him to make small gifts to the church and to the poor, even when he was a small boy.

He kept from boyhood an account of every cent he received and spent and gave away. The first of these account books, which later became famous as “Ledger A,” contained a record of everything. It showed that as a boy Rockefeller had given a cent to his Sunday school every Sunday. In one month there were entries of 10 cents to foreign missions, 12 cents to the Five Points Mission in New York, and 35 cents to his Sunday school teacher for a present.

Mr. Rockefeller discovered the secret of making money his slave at the age of 14. He had saved $50 from his turkey sales, other small enterprises and the performance of chores. Lending this at 7 percent, he received the principal and interest back at the end of a year. About the same time, he received $1.12 for three days of back-breaking labor, digging potatoes for a neighbor. On entering the two transactions in his ledger he realized that his pay for this work was less than one-third the annual interest on his $50, and he resolved to make as much money work for him as he could.

The Rockefeller family moved to a farm near Cleveland in 1853. Mr. Rockefeller spent a year and a half at the Cleveland High School. There he met Laura Celestina Spelman, whom he later married. He briefly attended a business college, learning bookkeeping and the fundamentals of commercial transactions.

At the age of 15 he joined the Erie Street Baptist Church, which had a $2,000 mortgage about to be foreclosed. Young Rockefeller stood at the door of the church begging contributions every Sunday until he raised enough to pay the debt. Two years later he was made a trustee of the church and was superintendent of the Sunday school for 30 years.

He got his first job on Sept. 26, 1855, at the age of 16. His first employers were Hewitt & Tuttle, who had a wholesale produce commission warehouse on the lakefront. At first he was a clerk and assistant bookkeeper. Ledger A showed that he received $50 for more than three months’ work, out of this paying his landlady and washerwoman.

In 1858, he went into the commission business for himself in partnership with Maurice B. Clark, an Englishman. Each put $2,000 into the business. He was the firm’s junior partner.

“We were prosperous from the beginning,” Mr. Rockefeller later told his Bible class. “We did a business of $450,000 the first year. Our profit was not large—I think about $4,400.”

Mr. Rockefeller was always “a great borrower,” as he said himself. He kept expanding his business and borrowed large sums to finance it.

He drove sharp bargains and continued to live frugally, saving money and putting it back into his business, so that he was prepared to seize the opportunity which came after oil was discovered in Pennsylvania in 1859.

Mr. Rockefeller went into the oil business in 1862. He and his partner, Clark, invested in a refinery planned by Samuel Andrews, who had learned how to refine the crude oil. A new firm was organized under the name of Andrews, Clark & Co. Although he would become the world’s best-known oil man, Rockefeller was so unknown that his name did not even appear in the firm.

Andrews, Clark & Co. built a small refinery on the bank of Kingsbury Run, near Cleveland, in 1863. In 1865 the partnership was dissolved and the plant offered at auction. Mr. Rockefeller bought it for $72,500 and organized the new firm of Rockefeller & Andrews. In 1867 this firm absorbed an oil refinery established by William Rockefeller, and took in as partners William Rockefeller and Henry M. Flagler.

This was the first of the long series of reorganizations and mergers that led to the formation of the great Standard Oil Trust. In 1870, when he was 31 years old, Mr. Rockefeller organized the original Standard Oil Company, with William Rockefeller, Andrews, Flagler and Steven V. Harkness. Mr. Rockefeller was president of the company.

By 1872 nearly all the refining companies in Cleveland had joined the Standard Oil Company. The company soon was refining 29,000 barrels of crude oil a day and making 9,000 barrels a day in its cooper shop. It owned several hundred thousand barrels of oil tankage and warehouses for storing refined oil.

Early conditions in the oil industry were so unstable that many companies were ruined by sharp fluctuations in the market. Mr. Rockefeller began preaching to his local competitors that they might be wiped out unless they had some mutual organization for protection, and inviting them to come into Standard Oil. Within two years nearly all of the petroleum refiners in Cleveland were members of the company.

The Pittsburgh refiners also merged into the Standard Oil combination, as did refiners in Philadelphia, New York, New Jersey, New England, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

In 1882 Mr. Rockefeller organized the Standard Oil Trust, holding the stocks of all these companies as well as of the original Standard Oil Company. Mr. Rockefeller was growing richer and more powerful every day.

In the Standard Oil Trust Mr. Rockefeller created a new form of commercial enterprise that marked the beginning of an era of modern industrial monopoly. Pipeline companies and other companies for gathering, distributing and marketing petroleum products around the world were organized, all working for the benefit of the trust.

Mr. Rockefeller effected great savings in the business. Standard Oil built its own pipelines, bought its own tank cars for transporting oil in train loads, and established its own depots and warehouses. It made its own barrels in its own shops, and bought whole forests of timber.

The name of Rockefeller spread around the world. His agents and steamships with their cargoes of oil invaded every port. His great corporation had established itself in control of oil production and distribution in America. Mr. Rockefeller began investing his profits in other industries, including iron, steamships and railroads. At the height of his career he directed the affairs of 33 oil companies and indirectly influenced hundreds of other companies. The original Standard Oil Company had assets of $55,000,000; the combined capitalizations of the corporations in which he was interested ran into the billions.

People began to denounce him as a menace and call the Standard Oil an octopus. The anti-trust movement began, and muckraking grew in fashion, with Rockefeller and Standard Oil as the chief targets.

Ida M. Tarbell wrote a book, “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” in which she attacked the business methods with which Mr. Rockefeller had created the Oil Trust. He was accused of crushing competition, getting rich on rebates from railroads, bribing men to spy on competing companies, making secret agreements, and coercing rivals to join the Standard Oil Company.

Mr. Rockefeller insisted that the Standard Oil was a good trust and that he had made his money honestly and honorably.

“Sometimes things are said about us that are cruel and they hurt,” he once said. “But I am never a pessimist. I never despair. I believe in man and the brotherhood of man and am confident that everything will come out for the good of all in the end.”

The Rockefellers had five children. Those living are Alta and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

At one time he had five homes. His town house was at 4 West 45th St. The 3,000-acre estate at Pocantico Hills, called Kikuit, was his favorite residence. Several years ago he bought an estate at Ormond Beach, Fla.

Mr. Rockefeller was friendlier to strangers in his later years. He distributed shiny new dimes among children he found playing in the street and to singers on the ferry between Tarrytown and Nyack.

HENRY FORD

July 30, 1863–April 7, 1947

DETROIT—Henry Ford, noted automotive pioneer, died at 11:40 tonight at the age of 83. He had retired a little more than a year and a half ago from active direction of the great industrial empire he founded in 1903.

Death came at his estate in suburban Dearborn, not far from where he was born in 1863. Mr. Ford was reported to have been in excellent health when he returned only a week ago from his annual winter visit to his estate in Georgia.

There were many reports that he had given up his leadership at the insistence of other members of his family, particularly the widow of his only son, Edsel B. Ford, who was said to be dissatisfied with the course of company affairs. After resigning as president late in 1945, Mr. Ford spent time at the Ford engineering laboratory.

He leaves a widow, the former Clara Bryant, whom he married in 1887, and two grandsons, Henry 2nd, who had assumed control of the company after Mr. Ford’s retirement, and Benson.

—The Associated Press

Henry Ford was the founder of modern American industrial mass production methods, built on the assembly line and the belt conveyor system, which no less an authority than Marshal Joseph Stalin testified were the foundation for an Allied military victory in the Second World War. He was the apostle of an economic philosophy of high wages and short hours that had immense repercussions on American thinking.

He lived to see the Ford Motor Company produce more than 29 million automobiles before the war forced the conversion of its gigantic facilities. Then he directed its production of more than 8,000 four-engine bombers, as well as tanks, tank destroyers, jeeps and amphibious jeeps, transport gliders, trucks, engines and much other equipment.

Struck a cruel blow shortly before his 80th birthday by the death of his only son, Edsel, on May 26, 1943, Mr. Ford remained at the helm as the company reached the peak of its war production.

Mr. Ford was born on July 30, 1863, on a farm nine miles west of Detroit, the eldest of six children. His mother died when he was 12 years of age. He went to school until he was 15. He worked on the farm after school hours and during vacations.

His mechanical bent first showed itself early. When he was 13 he took a watch apart and put it together again so that it would work. He had to do this secretly at night, after he had finished his chores, because his father wanted to discourage his mechanical ambitions. In 1879, at the age of 16, he ran away from home. Walking all the way to Detroit, almost penniless, he went to work as an apprentice in a machine shop.

Returning to his father’s farm, he spent his spare time for several years endeavoring to evolve a practical farm tractor of relatively small size and cost. He succeeded in building a steam tractor with a one-cylinder engine, but was unable to devise a boiler light enough to make the tractor practicable.

Convinced that the steam engine was unsuited to light vehicles, he turned to the internal combustion engine, which he had read about in English scientific periodicals, as a means of locomotion for the “horseless carriage” of which he and other automobile inventors had dreamed.

In 1890 he got a job as engineer and machinist with the Detroit Edison Company at $45 a month, and moved to Detroit. He set up a workshop in his backyard and continued his experiments after hours.

He completed his first “gasoline buggy” in 1892. It had a two-cylinder engine, which developed about four horsepower, and he drove it 1,000 miles. The first, and for a long time the only automobile in Detroit, it was too heavy to suit Mr. Ford, who sold it in 1896 for $200, to get funds to experiment on a lighter car. Later, when he became successful, he repurchased his first car for $100 as a memento.

Meanwhile, he had become chief engineer of the electric company at $125 a month. His superiors offered to make him general superintendent, but only on condition that he give up gasoline and devote himself entirely to electricity. He quit his job on Aug. 15, 1899.

Mr. Ford persuaded a group of men to organize the Detroit Automobile Company to manufacture his car. The company made and sold a few cars on his original model, but after two years Mr. Ford broke with his associates over a fundamental issue. He envisioned the mass production of cars that could be sold in large quantities at small profits, while his backers were convinced that the automobile was a luxury, to be produced in small quantities at large profits per unit.

Renting a one-story brick shed in Detroit, Mr. Ford spent 1902 experimenting with two-cylinder and four-cylinder engines. He built two racing cars, each with a four-cylinder engine developing 80 horsepower. One of the cars, with the celebrated Barney Oldfield at its wheel, won every race in which it was entered.

The publicity helped Mr. Ford to organize the Ford Motor Company, which was capitalized at $100,000, although actually only $28,000 in stock was subscribed. Eventually, he and his son bought out the minority stockholders for $70 million and became sole owners.

In 1903 the Ford Motor Company sold 1,708 two-cylinder, eight-horsepower automobiles. Its operations were soon threatened, however, by a suit for patent infringement brought by the Licensed Association of Automobile Manufacturers, who held the rights to a patent obtained by George B. Selden of Rochester, N.Y., in 1895, covering the combination of a gasoline engine and a road locomotive. Mr. Ford won the suit when the Supreme Court held that the Selden patent was invalid.

For several years, Mr. Ford was balked by the lack of a steel sufficiently light and strong. By chance one day, picking up the pieces of a French racing car that had been wrecked at Palm Beach, he discovered vanadium steel, which had not yet been manufactured in the United States.

With this material he began the era of mass production. He concentrated on a single type of chassis, the celebrated Model T, and specified that “any customer can have a car painted any color he wants, so long as it is black.” By 1925, the company was producing almost 2 million Model T’s a year.

In January 1914, he established a minimum pay rate of $5 a day for an eight-hour day. Up to then, the average wage throughout his works had been $2.40 a nine-hour day.

To reduce costs and eliminate intermediate profits on raw materials and transportation, Mr. Ford purchased his own coal mines, iron mines and forests, his own railways and his own lake and ocean steamships. The phenomenal success of the new system made Mr. Ford not only fabulously rich, but internationally famous.

In the winter of 1915–16 he was convinced by a group of pacifists that the warring nations in Europe were ready for peace and that a dramatic gesture would end the war. Mr. Ford chartered an ocean liner with the avowed purpose of “getting the boys out of the trenches by Christmas,” and sailed from New York on Dec. 4, 1915, with a curiously assorted group of companions. The mission failed to achieve anything. “We learn more from our failures than from our successes,” he said.

When the United States declared war on Germany in April, 1917, Mr. Ford placed the industrial facilities of his plants at the disposal of the Government, although he had previously refused orders from belligerent countries.

Mr. Ford retired as active head of the Ford Motor Company in 1918, at the age of 55, turning over the presidency to Edsel and announcing his intention of devoting himself to the development of his farm tractor, and to the publication of his weekly journal, The Dearborn Independent.

In 1919 Mr. Ford sued The Chicago Tribune for libel, because of an editorial that accused him of having been pro-German during the war. The jury awarded him a mere six cents, and only after counsel for the defense had subjected him to a pitiless cross-examination which revealed him to be almost without knowledge of subjects outside his own field. (It would not be unfair to say that, despite his vast wealth and industrial expertise, Mr. Ford remained in some ways a simple man. He believed in hard work and utilitarian education and was opposed to the use of tobacco and liquor. He tried in vain from time to time to interest the younger generation in old-fashioned dances and fiddlers.)

His activities as publisher of The Dearborn Independent involved him in another libel suit. The weekly published a series of articles, which were widely criticized as anti-Semitic. Aaron Sapiro, a Chicago lawyer, sued on the ground that his reputation as an organizer of farmers’ cooperative marketing organizations had been damaged by articles asserting that a Jewish conspiracy was seeking to control American agriculture.

On the witness stand, Mr. Ford disclaimed animosity toward Jews. It was brought out that, although a column in the paper was labeled as his, he did not write it nor did he read the publication. Mr. Ford settled the suit without disclosing the terms, discontinued the paper and made a public apology.

The 1921 depression brought the company its most severe financial crisis. Investment bankers were convinced that he would have to go to them “hat in hand,” and an officer of one large New York bank journeyed to Detroit to offer Mr. Ford a loan on the condition that a representative of the bankers be appointed treasurer of his company. Mr. Ford silently handed him his hat.

Mr. Ford loaded up Ford dealers throughout the country with all the cars they could handle and compelled them to pay cash. Then, by purchasing a railroad of his own, and by other economies, he cut one-third from the time his raw materials and finished products were in transit.

He realized more money from the sale of Liberty bonds, from by-products and from collections from Ford agents in foreign countries. On April 1, consequently, he had far more than he needed to wipe out the indebtedness. The crisis over, Mr. Ford severed all connections with the banks, except as a depositor. He made a practice of carrying tremendous amounts on deposit. Bankers reported that he invariably drove a hard bargain in placing these funds, often demanding a special rate of interest.

In 1924, the Ford company had manufactured about two-thirds of all the automobiles produced in this country, but by 1926 the Chevrolet, manufactured by the General Motors Corporation, had become a serious competitor.

Mr. Ford closed his plants late in 1926 while he experimented with a six-cylinder model. He abandoned the Model T the next year, substituting the Model A. The new model proved popular, and the Ford Motor Company continued to expand. In 1928 Mr. Ford organized the British Ford Company, and subsequently began operations in other European countries.

Mr. Ford had long regarded Soviet Russia as a potential market. By agreeing to aid in the construction of an automobile factory at Nizhni-Novgorod, and by providing technological assistance in the development of the automobile industry in the Soviet Union, Mr. Ford sold $30 million worth of products to Russia.

After the stock market collapse of October 1929, he was one of the business and industrial leaders who were summoned to the White House by President Hoover. Unlike some industrialists who favored deflation of wages, Mr. Ford argued that the maintenance of purchasing power was of paramount importance.

Although his company lost heavily in the worst of the Depression, Mr. Ford maintained his wage policy until the autumn of 1932, when the company announced a downward readjustment from “the highest executive down to the ordinary laborer.” As the Depression waned, he reverted to his high-wage policy and in 1935 established a minimum of $6 a day.

Mr. Ford opposed the New Deal, and he refused to sign the automobile code of the National Recovery Administration, which stipulated that employees had a right to organize. In 1936 he supported Gov. Alf M. Landon. Despite President Roosevelt’s triumphant re-election, Mr. Ford remained antagonistic to unions.

The United Automobile Workers began a drive to organize Ford workers. The opening blow was a sitdown strike in the Ford plant in Kansas City, ended only by the promise of officials there to [meet] with the union, a step the company had never taken before. Mr. Ford charged that international financiers had gained control of the unions.

On May 26, 1937, a group of UAW organizers were distributing organizing literature outside the Ford plant at River Rouge, when they were set upon and badly beaten. The union charged that the beatings were administered by company police. The company denied this.

The National Labor Relations Board found the company guilty of unfair labor practices. In April 1941, the UAW called a strike in the Ford plants, and the NLRB held an election. When the votes were counted, the UAW had won about 70 percent of the votes. Mr. Ford signed a contract that gave the union virtually everything for which it had asked.

Mr. Ford opposed American entry into World War II and refused to manufacture airplane motors for Great Britain. But as the pressure for re-armament grew, he felt compelled to build planes for the United States. Ground was broken on April 18, 1941, for the Willow Run plant, and the first of the 30-ton B-24-E bombers came off its assembly line a little more than a year later. Eventually the factory, well over a half-mile long, was turning out bombers at the rate of one an hour.

Notwithstanding his earlier opposition to unions, Mr. Ford said in a September 1944 interview that he wanted his company to pay the highest wages in the automobile industry: “If the men in our plants will give a full day’s work for a full day’s pay, there is no reason why we can’t always do it. Every man should make enough money to own a home, a piece of land and a car.”

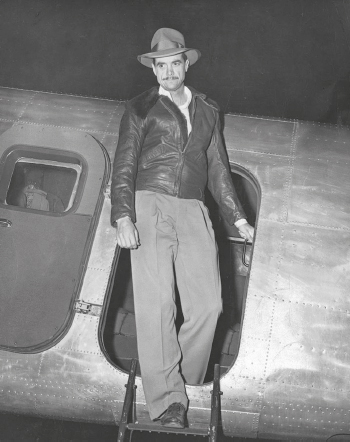

HOWARD HUGHES

December 24, 1905–April 5, 1976

By James P. Sterba

HOUSTON—Howard R. Hughes died today as mysteriously as he had lived.

The reclusive 70-year-old billionaire was on the way from Acapulco, Mexico, to a hospital for emergency treatment. A physician accompanying him said Mr. Hughes died at 1:27 P.M. in a chartered jet flying over south Texas.

A Hughes spokesman said the cause of death was a “cerebral vascular accident.” This is otherwise known as a stroke.

Two years ago one of Howard R. Hughes’s many lawyers appeared before a Federal court in Los Angeles in one of the many cases involving the reclusive billionaire.

Asked to explain the failure of his client to appear, the attorney, Norbert Schlei, said Mr. Hughes was “a man to whom you cannot apply the same standards as you can to you and me.”

He got no dispute on that point from judge or jury, although the case ended in one of the few setbacks Mr. Hughes ever encountered in court—a $2,823,333 defamation award to his former aide Robert A. Maheu.

Mr. Hughes had a role in a different kind of drama in 1974 as he and the Central Intelligence Agency teamed up to recover a sunken Soviet submarine from the Pacific Ocean floor. The submarine, which sank 750 miles northwest of Hawaii in 1968, held nuclear warheads and code books, and Mr. Hughes, at the behest of the C.I.A., commissioned the construction of a ship called the Glomar Explorer and a mammoth barge to retrieve the vessel. The project was conducted under the ruse of deep-sea research.

[The salvage attempt brought up half the submarine. The half containing the warheads and code books broke off during the operation and dropped three miles to the bottom again.]

No recent episode in Mr. Hughes’s life galvanized the attention of the world like the extraordinary sequence of events stemming from the announcement by McGraw-Hill and Life magazine on Dec. 7, 1971, that they planned to publish an “autobiography” of Mr. Hughes, as told to a little-known American writer named Clifford Irving.

Mr. Irving claimed to have met secretly with his subject more than 100 times for tape-recorded discussions and came forward with a 230,000-word manuscript entitled “The Autobiography of Howard Hughes.”

McGraw-Hill gave him $750,000 for it—a $100,000 advance and $650,000 in checks made out to “H. R. Hughes,” as payment to Mr. Hughes for his “cooperation.” Mr. Irving’s wife, Edith, using the name Helga R. Hughes, deposited the checks in a Swiss bank. McGraw-Hill sold excerpt rights to Life.

In an extraordinary telephone news conference, Mr. Hughes denounced the work as a hoax, sued to halt publication and promised to prove Mr. Irving was a fake. (He also charged that his aide, Mr. Maheu, “stole me blind,” leading to the aforementioned defamation verdict.)

Eventually, Edith Irving was exposed as the “Helga R. Hughes” who appeared in Switzerland. Evidence mounted that Mr. Irving’s manuscript resembled published and unpublished materials produced by others. In mid-February of 1972, Life and McGraw-Hill conceded the work was a hoax and canceled publication. Mr. Irving and his wife pleaded guilty and served jail sentences for their deception.

The news conference over the Irving affair was one of the rare instances in recent decades when the voice of Howard Hughes was heard in a relatively public setting. Normally, he saw only his round-the-clock male attendants (he favored Mormons because they did not smoke or drink) and his wife, Jean Peters, the actress he married in 1957. They were divorced in 1971 after a lengthy separation.

Mr. Hughes wasn’t always a recluse. Back in the nineteen-thirties, when he was setting air speed records and was a maverick Hollywood producer, the newspapers were full of photographs of a lean and smiling Mr. Hughes posing with Jane Russell, Lana Turner, Ava Gardner and other film and cafe society beauties.

Mr. Hughes set several air speed records and in 1938 flew around the world in 91 hours—a feat for which he was voted a Congressional medal. He never bothered to pick it up, however, and years later President Harry S. Truman found it in a White House desk and mailed it to him.

There were a number of explanations for Mr. Hughes’s reclusiveness, including his deafness, his shyness and a fear of germs that extended to separate refrigerators for himself and his wife, separate copies of magazines and newspapers and an unwillingness to shake hands.

In an interview about 25 years ago Mr. Hughes denied that he was eccentric: “I am not a man of mystery. These stories grow like Greek myths.… I have no taste for expensive clothes. Clothes are something to wear and automobiles are transportation. If they merely cover me up and get me there, that’s sufficient.”

After Mr. Hughes had settled in Nevada in 1966 and had invested more than $125 million in casinos and real estate, Gov. Paul Laxalt let it be known that he would like to speak with him. Shortly thereafter Mr. Hughes—or a voice that identified itself as his—telephoned the Governor. Mr. Hughes, according to Mr. Laxalt, was an occasional telephoner, and the two men sometimes conversed for an hour.

Shortly after his arrival in Las Vegas, Mr. Hughes bought the operating contracts of the Desert Inn for $13.25 million, and later the property as well. One story was that he had acted when the owners requested him to leave his $250-a-day suite to make way for already-booked guests. Another explanation was that the deal enabled Mr. Hughes to multiply his millions with relative tax freedom, given Nevada’s absence of state income or inheritance taxes.

A third, and perhaps complementary, explanation was that Mr. Hughes envisioned a huge regional airport that would transform Las Vegas into a terminal for the Southwest and California.

Through 1969, Mr. Hughes had invested about $150 million in Las Vegas properties. In addition, he bought Air West with 9,000 route miles in eight Western states, Canada and Mexico. The acquisition cost Mr. Hughes $150 million, but it put him back in the air travel business, which he had left when he sold his controlling interests in Trans World Airlines and Northeast.

Mr. Hughes operated through Mr. Maheu, a strapping ex-F.B.I. agent, and scores of subordinates, most of whom never saw him.

The anchor of Mr. Hughes’s fortune was the Hughes Tool Company, which manufactures and leases rock and oil drills. He owned, moreover, the Hughes Aircraft Company in California, which manufactures electronic devices as well as planes and holds many Government contracts.

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. was born on Christmas Eve, 1905, in Houston. He was shy and serious as a boy and showed mechanical aptitude early. He attended two preparatory schools. He also took courses at Rice Institute in Houston and the California Institute of Technology. He obtained no degree.

Mr. Hughes’s father was a mining engineer who developed the first successful rotary bit for drilling oil wells through rock. When his mother died in 1922, Howard Hughes inherited 50 percent of the company. On his father’s death in 1924, he received 25 percent. He took control of the company at 18, and two years later bought out the remaining family interest.

At 19, Mr. Hughes married Ella Rice, a member of the family that founded Rice Institute. The marriage lasted four and a half years.

Meanwhile, Mr. Hughes had shifted his interest to Hollywood, where he set forth, characteristically, in lone-wolf style, to become a movie producer. His first film was called “Swell Hogan,” and it was so bad it was never released.

But then came “Hell’s Angels,” starring Jean Harlow. Filmed in 1930 at a cost of $4 million, it was then the most expensive movie ever made. Much of the cost resulted when the picture was made over for sound, which had come into general use when it was half finished. Mr. Hughes wrote, produced and directed this film, which grossed $8 million.

Mr. Hughes turned out about a dozen pictures in the late twenties and early thirties. By then, he had become intrigued with aviation. He learned to fly during the filming of “Hell’s Angels” and was seriously injured when his plane, of World War I vintage, crashed.

In 1943 he was injured when an experimental two-engine flying boat crashed and sank in Lake Mead. And in 1946 he crashed on the first flight of his XF-11, a high-speed, long-range airplane. His chest and left lung were crushed; he also suffered a skull fracture and had nine broken ribs. During his recovery, he designed a new type of hospital bed.

Mr. Hughes’s aviation achievements were overshadowed for a time by a notable failure—the Hughes flying boat. This eight-engine seaplane, built of plywood, was conceived by Mr. Hughes during World War II, when a shortage of metal dictated the use of alternate materials. The Spruce Goose, as it was dubbed by the press, was designed to carry troops. It had a wing spread of 320 feet, a hull three stories high and a tail assembly eight stories tall.

The Government put $18 million into the plane, and Mr. Hughes said he had invested $23 million. The craft flew only once—on Nov. 2, 1947, when, with Mr. Hughes at the controls, it got about 70 feet off the water for a one-mile run.

Before the war was over, Mr. Hughes had returned to independent motion-picture production. The occasion was a film that proved to be his most controversial, “The Outlaw,” starring Mr. Hughes’s personal discovery, Jane Russell.

Filmed in 1941–42, the western was denied a seal of approval by the Motion Picture Association of America because of greater exposure of Miss Russell than was customary. Shown in San Francisco in 1943, the picture ran into a storm of protest and censorship and was temporarily withdrawn. In 1946, it was put into general distribution, with Mr. Hughes reaping both profits and publicity.

Two years later, Mr. Hughes bought a controlling interest in the Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corporation for $8,825,000. Under Mr. Hughes, R.K.O. was constantly in the red and he was accused in one of the many stockholder suits of running the studio with “caprice, pique and whim.” In 1954, he bought up the outstanding stock of R.K.O. But by mid-1955 he was tired of the movies and sold his studio interest.

In his later years Mr. Hughes was engaged in a long-running battle over Trans World Airlines, which he lost control of in 1961 to creditors who had financed the purchase of jets for the line. The new trustee management and Mr. Hughes sued each other, but Mr. Hughes refused to appear in court. Then on April 9, 1966, came the surprise news that he was selling his 78 percent interest in T.W.A. for about $546 million.

Characteristically, Mr. Hughes had no comment.

RAY KROC

October 5, 1902–January 14, 1984

By Eric Pace

Ray A. Kroc, the builder of the McDonald’s hamburger empire, who helped change American business and eating habits by deftly orchestrating the purveying of billions of small beef patties, died yesterday in San Diego. He was 81 years old and lived in La Jolla, Calif.

Mr. Kroc, who also owned the San Diego Padres baseball team, died of a heart ailment at Scripps Memorial Hospital in San Diego. At his death he was senior chairman of McDonald’s.

Mr. Kroc, a former piano player and salesman of paper cups and milkshake machines, built up a family fortune worth $500 million or more through his tireless, inspired tinkering with the management of the McDonald’s drive-ins and restaurants, which specialize in hamburgers and other fast-food items.

He was a pioneer in automating and standardizing operations in the fiercely competitive fast-food industry. He concentrated on swiftly growing suburban areas, where family visits to the local McDonald’s became something like tribal rituals.

He started his first McDonald’s outside Chicago in 1955, and the chain now has 7,500 outlets in the United States and 31 other countries and territories, registering more than $8 billion in sales in 1983. Three-quarters of its outlets are run by franchise-holders. It is the United States’ largest food service organization in sales and number of outlets.

What made Mr. Kroc so successful was the variety of virtuoso refinements he brought to fast-food retailing. He carefully chose the recipients of his McDonald’s franchises, seeking managers who were skilled at personal relations; he relentlessly stressed quality, banning from his hamburgers such filler materials as soybeans.

Mr. Kroc also made innovative use of part-time teen-age help; he struggled to keep costs down to make McDonald’s perennially low prices possible, and he applied complex team techniques to food preparation that were reminiscent of professional football.

After McDonald’s had made him a major figure on the business scene, Mr. Kroc became influential in the sports world by buying the San Diego Padres for $10 million in 1974.

The new and eager team owner was notably outspoken: After his club botched a game in 1974, he used the San Diego Stadium public address system to tell the team’s fans, “I suffer with you; I’ve never seen such stupid ball playing in my life.”

In the major leagues of American business, Mr. Kroc’s career was unusual because its enormous success was so late in coming. He was in his 50’s when he went into the hamburger business, making himself president of the McDonald’s Corporation in 1955. In 1968 he became chairman, and he took the title of senior chairman in 1977, when McDonald’s purveyed more than $3.7 billion worth of fast-food fare, outselling its archcompetitor, the Pillsbury-owned Burger King, by 4 to 1.

McDonald’s shares were a Wall Street favorite in the early 70’s. By January 1973, investors who bought them when first offered in the mid-1960’s had seen their wealth multiply more than sixtyfold.

Over the years, Mr. Kroc was repeatedly involved in controversy. The authors Max Boas and Steve Chain charged in a 1976 book, “Big Mac: The Unauthorized Story of McDonald’s,” that McDonald’s had exploited its employees by forcing them to take lie-detector tests and by appropriating their tips. The architecture of McDonald’s outlets was sometimes criticized, as was the nutritional content of the food. But one critic, the nutritionist Jean Mayer, once said, “I am nonfanatical about McDonald’s; as a weekend treat, it is clean and fast.”

In 1972 Senator Harrison A. Williams Jr., Democrat of New Jersey, suggested that there was a link between the more than $200,000 that Mr. Kroc had contributed to President Nixon’s re-election campaign and the Nixon Administration’s position on teen-age wage limits, a matter of prime importance to McDonald’s.

Mr. Kroc cut a commanding figure, his thin hair brushed straight back, his custom-made blazers impeccable, his eyes constantly checking his restaurants for cleanliness. He sought followers who, like him, were driven by an unending urge to build and excel.

“We want someone who will get totally involved in the business,” he once said. “If his ambition is to reach the point where he can play golf four days a week or play gin rummy for a cent a point, instead of a tenth, we don’t want him in a McDonald’s restaurant.”

Understandably, many McDonald’s executives decorated their offices with scrolls inscribed with his favorite inspirational dictum:

Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.

Mr. Kroc established the McDonald’s headquarters in Oak Brook, a few miles from the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, where he was born Oct. 5, 1902, the son of an unsuccessful real estate man whose family came from Bohemia in what is now Czechoslovakia.

Ray Albert Kroc did not graduate from high school. In World War I, like his fellow Oak Parker, Ernest Hemingway, he served as an ambulance driver. Then, after holding various jobs, including playing piano in a jazz band, he spent 17 years with the Lily Tulip Cup Company. But by 1941, “I felt it was time I was on my own,” Mr. Kroc once recalled, and he became the exclusive sales agent for a machine that could prepare five milkshakes at a time.

Then, in 1954, Mr. Kroc heard about Richard and Maurice McDonald, the owners of a fast-food emporium in San Bernadino, Calif., that was using his mixers. As a milkshake specialist, Mr. Kroc later explained, “I had to see what kind of an operation was making 40 at one time.”

“I went to see the McDonald operation,” Mr. Kroc went on in a memoir published in The New York Times, and suddenly insights gained during his years in the paper-cup business and the milkshake machine business mingled fruitfully in his mind.

“I can’t pretend to know what it is—certainly, it’s not some divine vision,” he said of his touch in business. “Perhaps it’s a combination of your background and experience, your instincts, your dreams. Whatever it was, I saw it in the McDonald operation, and in that moment, I suppose, I became an entrepreneur. I decided to go for broke.”

Mr. Kroc talked to the McDonald brothers about opening franchise outlets patterned on their restaurant, which sold hamburgers for 15 cents, french fries for 10 cents and milkshakes for 20 cents.

They later worked out a deal whereby he was to give them a small percentage of the gross of his operation. Mr. Kroc’s first restaurant opened in 1955 in Des Plaines, another Chicago suburb. Five years later, there were 228 restaurants, and in 1961 he bought out the brothers.

In choosing franchise owners, Mr. Kroc looked, as he explained it in 1971, “for somebody who’s good with people; we’d rather get a salesman than an accountant or even a chef.”

Among the license holders were a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia, a chemist, a golf professional, dentists, lawyers and even a former Under Secretary of Labor.

McDonald’s poured hundreds of millions of dollars into advertising. One head of another fast-food company said in 1978 that consumers were “so preconditioned by McDonald’s advertising blanket that the hamburger would taste good even if they left the meat out.”

Mr. Kroc was also unremittingly intense in training his franchise owners at “Hamburger University” in Elk Grove, Ill., where a course led to a “Bachelor of Hamburgerology with a minor in french fries.” Instructors taught how to clean grills, flip a hamburger and tell when one was done. “It starts turning brown around the edge.”

Mr. Kroc met his wife, Joan, in a restaurant in 1956 when he and she had other spouses. They were married in 1968, and she went on to found and become the head of Operation Cork, a national program to help the families of alcoholics.

Mr. Kroc suffered a stroke in December 1979. His survivors include his wife, a brother, a sister, a stepdaughter and four granddaughters.

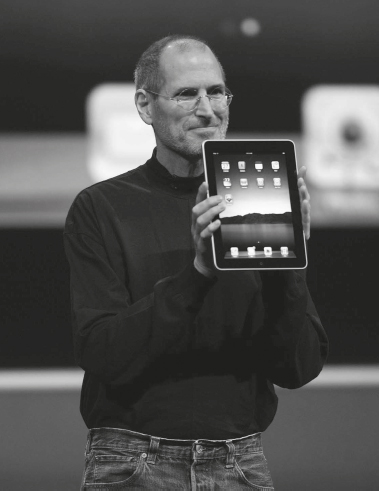

STEVE JOBS

February 24, 1955–October 5, 2011

By John Markoff

Steven P. Jobs, the visionary co-founder of Apple who helped usher in the era of personal computers and then led a cultural transformation in the way music, movies and mobile communications were experienced in the digital age, died on Wednesday. He was 56.

The death was announced by Apple, the company Mr. Jobs and his high school friend Stephen Wozniak started in 1976 in a suburban California garage. A friend of the family said the cause was complications of pancreatic cancer.

Mr. Jobs had waged a long and public struggle with the disease, remaining the face of the company even as he underwent treatment, introducing new products for a global market in his trademark blue jeans even as he grew gaunt and frail. He finally stepped down in August.

By then, having mastered digital technology and capitalized on his intuitive marketing sense, Mr. Jobs had largely come to define the personal computer industry and an array of digital consumer and entertainment businesses centered on the Internet. He had also become a very rich man, worth an estimated $8.3 billion.

Eight years after founding Apple, Mr. Jobs led the team that designed the Macintosh computer, a breakthrough in making personal computers easier to use. After a 12-year separation from the company, prompted by a bitter falling-out with his chief executive, John Sculley, he returned in 1997 to oversee the creation of one innovative digital device after another—the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad. These transformed not only product categories like music players and cellphones but also entire industries, like music and mobile communications.

During his years outside Apple, he bought a tiny computer graphics spinoff from the director George Lucas and built a team of computer scientists, artists and animators that became Pixar Animation Studios. It made the full-length computer-animated film a mainstream art form enjoyed by children and adults worldwide.

Mr. Jobs was neither a hardware engineer nor a software programmer, nor did he think of himself as a manager. He considered himself a technology leader, choosing the best people possible, encouraging and prodding them, and making the final call on product design.

It was an executive style that had evolved. In his early years at Apple, his meddling maddened colleagues, and his criticism could be caustic and even humiliating. But he grew to elicit extraordinary loyalty.

To his understanding of technology he brought an immersion in popular culture. His worldview was shaped by the ’60s counterculture in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he had grown up, the adopted son of a Silicon Valley machinist. When he graduated from high school in Cupertino in 1972, he said, “the very strong scent of the 1960s was still there.”

After dropping out of Reed College, a stronghold of liberal thought in Portland, Ore., in 1972, Mr. Jobs led a countercultural lifestyle himself. He told a reporter that taking LSD was one of the two or three most important things he had done in his life.

Apple’s very name reflected his unconventionality. In an era when engineers and hobbyists tended to describe their machines with model numbers, he chose the name of a fruit, supposedly because of his dietary habits at the time.