ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE

July 29, 1805–April 16, 1859

The London Times announces the death of the distinguished author of “Democracy in America”; an event for which previous reports of his rapidly declining health had prepared us.

The intelligence will be of melancholy interest to the multitudes in this country, who have read that capital production, and of personal regret to the survivors of those who enjoyed the gratification of intercourse with him during his travels through the United States, more than a quarter of a century ago.

Alexis Clerel de Tocqueville, a great-grandson of the loyal and philosophic Malesherbes, was born at Verneuil, July 29, 1805. Having completed his legal studies at Paris, he was named, in 1826, Judge of Instruction at Versailles, and in 1830 Alternate Judge. The following year he was selected with his friend E. G. de Beaumont to visit the United States in order to report upon the penitentiary systems of the several States.

The first fruit of his expedition was the “Démocratie en Amérique,” which he published in 1835. The work was received with extraordinary applause. Royer-Collard described it as “a continuation of Montesquieu”; it had numberless editions, was translated into nearly every European language, and in 1836 received the Montyon prize. The next year, M. de Tocqueville was elected to the Academy of Sciences, and in 1841 to a seat in the French Academy. With his journey to America, the judicial career of M. de Tocqueville closed.

In 1839 he was chosen to the Chamber of Deputies from Valogne, Department of La Manche, retaining his seat until 1848, aiding consistently the opposition to the Administration of Louis Philippe. The January of the latter year, he predicted the approach of the revolution, which actually broke out in the month following. The Department of La Manche chose him its representative in the Constituent Assembly, where he distinguished himself by his hearty reprobation of Socialism, but otherwise sustained the Republic.

Gen. [Louis-Eugène] Cavaignau, during his brief administration, selected M. de Tocqueville to represent France in the Brussels Conferences on Italian affairs. On his return from this mission, he was re-elected to his seat in the Deputies; and on the 3rd of June, 1810, received from the hands of President Louis Napoleon the portfolio of Foreign Affairs, and advocated the occupation of Rome, with all his powerful abilities.

The peculiar views, on this subject, announced in the President’s Message of Oct. 31, led to the resignation of the moderate members of the Cabinet, M. de Tocqueville among the number. In the Legislative Assembly the ex-Minister at once took position on the benches of the Opposition.

On the 2nd December 1851, he was one of the deputies who met to protest against the coup d’etat. Imprisoned, with his principal associates, he was presently set at liberty; and finally withdrew to private life.

His latest publication was “L’ancien Régime et la Révolution, 1856.” His closing days have been spent in the South of France, chiefly at Lannes, the seat of Lord Brougham’s Summer residence.

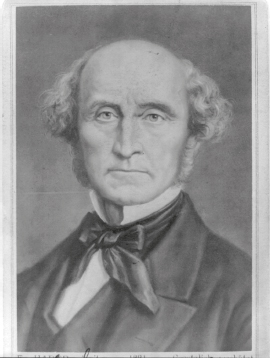

JOHN STUART MILL

May 20, 1806–May 8, 1873

LONDON—John Stuart Mill is dead. Intelligence of his death at Avignon, France, reached here at 3 o’clock this afternoon.

There are only two or three great thinkers in a century, and the loss of one of them is an incident notable in the world’s history. Such an event occurred two days ago, when Mr. John Stuart Mill died at Avignon.

This remarkable man was from his birth placed in circumstances peculiarly favorable to the development of his genius. He was a conspicuous instance of hereditary talent. His father, James Mill, was, like so many other men eminent in philosophical science, a Scotchman. He took orders at the University of Edinburgh, where he gained great distinction.

In 1798 he was licensed to preach, but he turned his back upon the pulpit, and became one of the throng of literary aspirants in the English metropolis. He subsequently became editor of the Literary Journal and contributed to the Edinburgh Review, which had just burst upon the world.

It was in 1806, just when he had commenced his History of India, that his son was born and christened John Stuart, after a Scottish baronet who had befriended his father. Mr. James Mill’s work on British India had a considerable bearing on the fortunes of his son, for the ability and knowledge displayed in it resulted in his appointment to a position in the East India Company’s office.

It was the father’s connection with this establishment which led to the son’s entering it, and when only 17, John Stuart Mill entered upon his duties as a clerk in the India House.

The circumstance is noteworthy as showing what a remarkable man can do as compared with an ordinary one under the same circumstances. Hundreds, nay thousands, of young men have entered the India House but were never heard of afterward, while this one man, leading the life of what has been termed a man mummy—a clerk in a Government office—has made a reputation which may endure as long as a mummy itself.

In 1820 Mr. John Stuart Mill went to France, where he attained a perfect knowledge of the French language and formed a perfect acquaintance with the history, politics, and literature of that country. Returning thence, he in 1823 entered the India Office as a subordinate clerk, where he was destined to remain until the extinction of the old East India Company in 1858. He was then offered a seat in the new council, appointed on the reconstruction of the department, which passed into the hands of the Crown, but declined to enter on the service of a new mistress, and retired.

Thrown in his father’s house among many of the most aspiring minds of the day, and running over with eager thought, it was to be expected that Mr. J. S. Mill should early have commenced to give utterance to his opinions on paper, and in 1830 the agitation in reference to the Reform bill offered a tempting opportunity for him to embark in the field of periodical literature. He began to write much in various newspapers and reviews, and it need not be said that his advocacy was persistently in the cause of liberalism.

It was about this time that he fell in with a young man several years his junior, on whom he exerted great influence and through whom he probably exercised much influence on others. This was Sir William Molesworth, a young baronet of family and fortune. In 1835 Sir William purchased the Westminster Review, which, conjointly with his friend, he edited, and it became the vehicle of many of those views which the editors desired to bring before the public.

In 1843 Mr. J. S. Mill published his Logic, which soon became a standard work. This was followed, in 1844, by Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy, and, in 1848, by Principles of Political Economy. These works were only a few out of many, but they contributed to his lasting fame as a philosophic thinker.

In 1865 Mr. Mill made what many regard as the only error in a faultless life by entering Parliament. Men 50 times his inferior found themselves equal to him, if not superior, in the mere power of pouring out words and expressing themselves attractively. He was dubbed “a mere book in breeches,” and the feeling was general that he was not the right man in the right place.

In 1868 he retired. His wife’s death occurred soon after, a blow from which he never recovered, and most of his remaining days were spent in the charming old town of Avignon, where the couple had spent many of their happiest hours.

It is almost impossible to estimate the influence such a mind as that of Mill exercises over his contemporaries. Its immediate influence is felt by only such a narrow circle as may be compared to that formed by a stone thrown into a pond, but each circle forms another until the effect becomes enormous. The immense value of such a mind lies in its extraordinary suggestiveness, combined with absolute purity in the motives for making suggestions.

To him, indeed, may well be applied those words of a great man in regard to his brother philosopher, [Thomas] Hobbes: “His is a great name in philosophy, on account both of the value of what be taught and the extraordinary impulse he communicated to the spirit of free inquiry.”

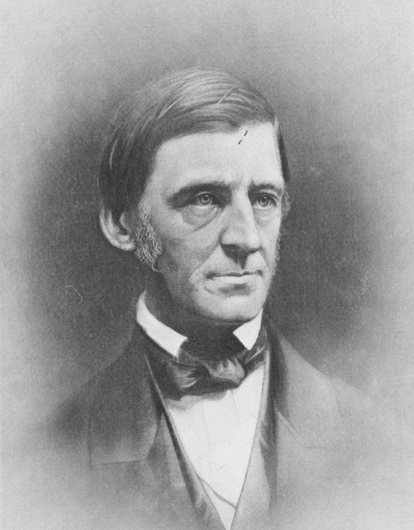

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

May 25, 1803–April 27, 1882

CONCORD—Ralph Waldo Emerson died this evening at 8:50 o’clock. His death was, after all, somewhat sudden, and when the crisis had nearly passed there was believed to be fair reason to expect that improvement would follow. He suffered little pain the early part of the day and had only very slight fever, but as the day advanced he grew weaker. At about noon the patient began to display increased difficulty in breathing and to suffer pain, which speedily grew so intense that ether was administered him. It was while unconscious of pain and of his surroundings that he passed away.

At 9:30 o’clock the news was announced to the townspeople by the 79 strokes being sounded—the bell of the Unitarian church tolling the years of his life. To the Concord people this death came as a personal loss. He was as beloved by the people about him for the sweetness of his disposition and his uniform kindliness as he was honored for the wealth of his intellect and the exalted position he held among thinkers and men of letters of two continents.

The disease from which he died is pronounced acute pneumonia.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was conspicuously of the best blood of New England. He was born in Boston, May 25, 1803, his father being the Rev. William Emerson, Pastor of the First (Unitarian) Church of that city. The boy lost his father when he was but eight—a loss he always deplored—and was then placed in a public grammar school until fitted to enter the Latin school, where he made his first ventures in composition. They were precocious verses, having reference to the purpose of life, the destiny of man, the mission of beauty, half-dreamy, half-mystical, unconventional, very much, it must be confessed, like many of the poems he produced in his maturity.

He was considered gifted but peculiar, and predictions were made—they were verified in his case—of his future celebrity. He entered Harvard at 14 and was graduated at 18. One who knew him in those days has described him as “a slender, delicate youth, younger than most of his classmates, and of a sensitive, retiring nature.” In the recitation room he did always well with Greek and Latin, but in philosophy he did poorly, and mathematics were “his utter despair.”

Leaving college, and having little means, he followed the customary course of New England youth, and taught school, continuing for five years. At 23 he had qualified himself for the pulpit, and in his 29th year was chosen colleague of Henry Ware, Jr., of the Second Unitarian Church. He had been there scarcely three years when he began to cherish doubts as to his belief. Granted permission to withdraw from his office, and shaking off all traditions of creed and authority, he stepped, as he said, into the free air and open world to utter his private thought to all who were willing to hear it.

From that hour dates the untrammeled life of Ralph Waldo Emerson as the present and many of a past generation know and knew him. He was very slow to gain recognition as an author, and well-nigh any man might have been dispirited by the lack of appreciation which so long attended him. But he had invincible faith in himself, and he waited patiently until he had found his audience and his audience had found him.

No American or European has been so fastidious as he respecting publication. He believed that a book should have every reason for being; that nothing trivial, passing, or temporary should be introduced into it; that the sole excuse for a book should be the presentation of fresh thought; that its contents should be in some manner an addition to the common stock of knowledge. If he had less vanity than members of his craft generally, he had more pride, more regard for his reputation, more confident expectation of enduring fame. He published what was universal and abiding in interest and influence, and compressed his utterances into the smallest space. Had all writers followed his example how immeasurably libraries would have been reduced!

The lectures of the American Plato, as he has been termed, soon found admirers in Boston. It became the mode of certain highly cultured sets in that city to extol the new light, the young transcendentalist, and being the mode, some who raved about him failed to understand him. Still, the great majority of his hearers were in harmony with his thought, and were sincere in their enthusiasm. Many became his disciples. The cheap wits of the day ridiculed his mysticism and studied opacity, as they were pleased to regard it, and decried all admiration of Emerson as a transparent affectation.

Jeremiah Mason, who ranked, in his day, as one of the foremost of New England lawyers, was induced to attend a course of Emerson’s lectures. Asked what he thought of them, he replied: “They are utterly meaningless to me, but my daughters, aged 15 and 17, understand them thoroughly.” This was repeated far and wide as a jest, but it may have been, probably was, literally true. A purely legal mind like Mason’s was not of the kind to appreciate the speculative, idealistic mind of the lecturer, and it is not at all unlikely that the imaginative, intuitive, poetic girls caught at once what eluded their father’s perception.

Mr. Emerson’s first publication was a thin volume entitled “Nature” (1836), in eight chapters, embracing “Commodity,” “Beauty,” “Language,” “Discipline,” “Idealism,” “Spirit,” and “Prospects.” It was virtually a pamphlet, but such a pamphlet as has seldom been issued. It had a new voice and a new strength, and its introduction was a key to whatever its author said afterward. Here are the opening words:

“Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, and criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?… There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.”

The transcendentalists needed an organ, and a quarterly, the Dial, was started (1840), with Margaret Fuller as editor, assisted by Emerson. It was exceedingly clever, even brilliant; it represented faithfully its class; but its class was too restricted, too far removed from the ordinary concerns of life, to place it on a substantial basis. As its editor said, Pegasus is a divine steed, though he cannot be expected to draw the baker’s cart to one’s door. Consequently it died after four years.

In 1841 the poet philosopher’s first volume of “Essays” appeared, treating such subjects as self-reliance, compensation, love, friendship, prudence, heroism, art, character, intellect, experience, and in so novel, eloquent, and sagacious a manner that the volume would have been eagerly sought had it not run counter to the theological prejudices of Beacon-street, and startled well-regulated conservatism from its propriety by audacious paradoxes and iconoclastic judgments.

In 1876 Mr. Emerson collected a dozen essays into “Letters and Social Aims,” practically his last volume. The final essay is “Immortality,” and in it occurs this passage: “Sixty years ago… we were all taught that we were born to die, and over that all the terrors that theology could gather from savage notions were added to increase the gloom. A great change has occurred. Death is seen as a natural event and is met with firmness. A wise man in our time caused to be written on his tomb, ‘Think on living!’ That inscription describes a progress in opinion. Cease from this antedating of your experience! Sufficient to to-day are the duties of to-day. Don’t waste life in doubts and fears! Spend yourself on the work before you, well assured that the right performance of this hour’s duties will be the best preparation for the hours that follow it.

‘The name of death was never terrible

To him that knew to live.’”

Anyone who may turn over the pages of Emerson must be struck with the number of phrases, and especially with the forms of expression, he has given to our mother tongue. The speech and writing of many cultured persons are stamped with his individuality. His pages are laden with aphorisms, and they are so felicitously put, and on such a variety of themes, that the capturing memory declines to surrender them, and speedily claims them as its own. How incessantly are we hearing these and hundreds of others?

Consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

Every man is a quotation from all his ancestors.

The devil is an ass.

No great men are original.

To be great is to be misunderstood.

Emerson appears to have acted his own definition of a philosopher—he reported to his own mind the constitution of the universe. He looked calmly at everything, into it, through it; and when aught came to him from within or without he jotted it down, not mentally merely, but actually. At all times he followed the habit, in the street or in his study, at midnight or morning. His wife, as the story goes, sometimes asked him when he had arisen in the watches of the night, “Are you ill, Waldo?” “No, dear,” from the self-poised husband, “only an idea.”

He had been twice married, first, when 27, to Ellen L. Tucker, of Boston, who died a few months after; secondly, three years later, to Lidian Jackson, of Plymouth, Mass. He has had three children, a son and two daughters, who are clever and capable. His home at Concord is described as a “plain, square wooden house, standing in a grove of pine trees.” It was along the road facing which Mr. Emerson’s house stands that the British troops marched on the memorable 19th of April, 1775.

Apparently absorbed in transcendentalism, Mr. Emerson always managed his affairs with intelligence and thrift. No immersion in the mysticism of the Bhagavad Gita could render him unmindful of duty to his family, the keeping of an engagement or the advantage of an investment. Of worldly goods he naturally had little; but of the little he made the most, and always kept rigorously clear of debt. No preoccupation with the planets caused him to forget his individual obligations or the quantity of coal in the cellar. A man so rounded, so conscientious, apart from what he was as scholar and thinker, could not fail by example to enrich in some sort our national life, for to live as high as we think is rarer than the rarest genius.

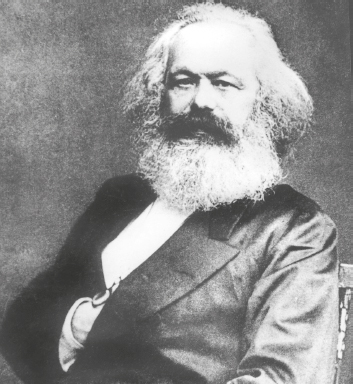

KARL MARX

May 5, 1818–March 14, 1883

LONDON—Dr. Friederich Engel [Friedrich Engels], an intimate friend of Karl Marx, says Herr Marx died in London, near Regent’s Park. Dr. Engel was present at the time of his death, which was caused by bronchitis, abscess of the lungs, and internal bleeding. He died without pain.

In respect to the wishes of Herr Marx, who always avoided a demonstration, his family have decided that the funeral shall be private. About 18 persons will be present, including a few friends who are coming from the Continent. The place of interment has not been announced. Dr. Engel will probably speak at the grave. There will be no religious ceremony. At the time of his death the third edition of Herr Marx’s book, “Das Kapital,” first published in 1864, was in preparation for the press.

Karl Marx, the German Socialist and founder of the International Association, was born in Cologne in 1818, and after studying philosophy and the law at the Universities of Bonn and Berlin became the editor of the Rhenish Gazette, in 1842. The opinions which he published were of so radical a character that the paper was suppressed the following year.

He then went to France, where he devoted himself to the study of political economy and social questions, and published in the Franco-German Tear Book, in 1844, “A Critical Review of Hegel’s Philosophy” and “The Holy Family against Bruno and His Consorts,” a satire on German idealism.

Expelled from France on the demand of the Prussian Government, he went to Belgium. He afterward took part in the Working Men’s Congress in London in 1847, and was one of the authors of the manifesto of the Communists. He was in Paris during the revolution of February, 1848, and then returned to Cologne, where he founded a paper called the New Rhenish Gazette.

After the dissolution of the Prussian Chambers, Marx advised the people to organize and resist the collection of the imposts, and for this his journal was a second time suppressed. He continued the agitation against the tax, and was arrested several times, but always acquitted by the jury on trial. He was finally banished from Germany, and returned to Paris, where he took part in the stormy scenes of the June disturbances, for which he was imprisoned, but managed to escape to London, where he established himself permanently.

There, in 1864, he founded the Association of Working Men, since known as the “International.” Herr Marx was the leading spirit of the first Central Council of that organization, which framed the laws which were adopted at the Geneva congress in 1866. He became the Corresponding Secretary for Germany and Russia, and from that time was the real Director of the International.

In 1871 he was attacked by the English section of the association and pronounced an unfit man to be a leader of the working classes. The schism was broadened in 1872, at the congress held at The Hague, when the Central Council at London was repudiated and Marx was deposed from his office as Secretary. The Internationals then divided into two factions—the Centralists, with Marx at their head, who transferred the headquarters of the Central Council to this City, and the Federalists, who had thrown Marx overboard.

Marx continued to reside in London, where he was for many years a correspondent of a New York paper. Among the works published by him are “A Treatise on Free Exchange,” “The Misery of Philosophy,” which is an answer to Proudhon’s “Philosophy of Misery,” and “Capital; a Criticism of Political Economy,” which is a complete exposition of the author’s doctrines.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

October 15, 1844–August 25, 1900

WEIMAR, GERMANY—Prof. Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, the philosopher, died here today of apoplexy.

Prof. Nietzsche was one of the most prominent of modern German philosophers, and he is considered the apostle of extreme modern rationalism and one of the founders of the socialistic school, whose ideas have had such a profound influence on the growth of political and social life throughout the civilized world.

Nietzsche was largely influenced by the pessimism of [Arthur] Schopenhauer, and his writings, full of revolutionary opinions, were fired with a fearless iconoclasm which surpassed the wildest dreams of contemporary free thought. His doctrines, however, were inspired by lofty aspirations, while the brilliancy of his thought and diction and the epigrammatic force of his writings commanded even the admiration of his most pronounced enemies, of which he had many.

Of Slavonic ancestry, Nietzsche was born in 1844 in the village of Röcken, on the historic battlefield of Lützen. He lost his parents early in life, but received a fine education at the Latin School at Pforta, concluding his studies at Bonn and Leipsic. Although educated for the ministry, Nietzsche soon renounced all faith in Christianity on the ground that it impeded the free expansion of life. He then devoted his attention to the study of Oriental languages and accepted in 1869 a professorship at the University of Basel, Switzerland.

This position he held until 1876, when overwork induced an affection of the brain and eyes, and he had to travel for his health. During these years of suffering and while in distressed circumstances he wrote most of his works.

Since 1889 Nietzsche had been hopelessly insane, living in Weimar, at the home of his sister, Elizabeth Forster-Nietzsche, who has edited his works. For many years he was a close friend of Richard Wagner, the composer. His principal publications are “The Old Faith and the New,” “The Overman,” “The Dawn of Day,” “Twilight of the Gods,” and “So Spake Zarathustra,” which is perhaps the most remarkable of his works.

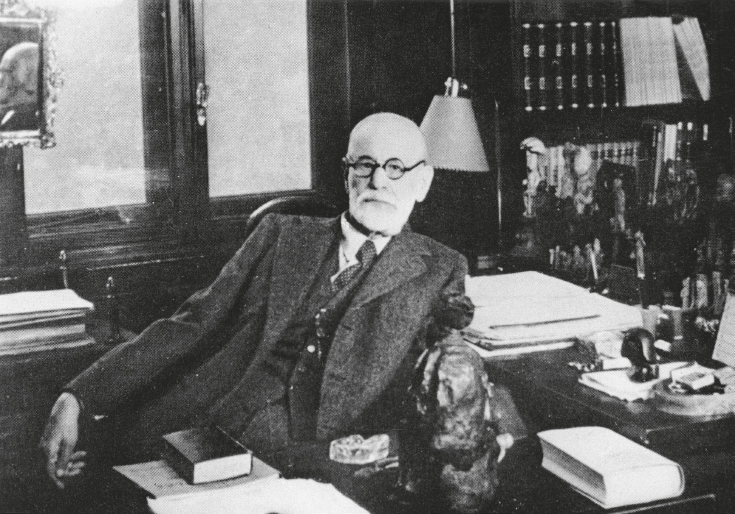

SIGMUND FREUD

May 6, 1856–September 23, 1939

LONDON—Dr. Sigmund Freud, originator of the theory of psychoanalysis, died shortly before midnight tonight at his son’s home in Hampstead at the age of 83.

Dr. Freud fled from Austria last year when the country was invaded by Germany and had been living with his son, Dr. Ernst Freud. He had been in ill health for more than a year and yesterday he passed into a coma from which he never rallied.

One of the most widely discussed scientists of the present day and originator of countless new ideas in the field of psychology, Dr. Sigmund Freud was a man who never compromised but often modified. In his long and stormy career he set the entire world talking about psychoanalysis, the method which he originated and in which he dramatized for mankind the hampering force of inhibitions.

“The mind is an iceberg—it floats with only one-seventh of its bulk above water” was one of his metaphorical statements on the vast preponderance of the subconscious element in human life. Another was, “The conscious mind may be compared to a fountain playing in the sun and falling back into the subterranean pool of the subconscious from which it rises.”

Probably the most radical departure from the old psychology introduced in Dr. Freud’s science of psychoanalysis was that man is a willing rather than a thinking animal. Previous to his time psychology had been overwhelmingly “intellectual,” regarding images, perceptions and ideas as the fundamental factors in mental life. But Dr. Freud laid the main stress of his system on the element of will or desire, relegating intellect to the background.

It was under this new system that Dr. Freud was able to explain many of the old “mysteries” of life, particularly regarding the fantasies and delusions of the deranged mind, and to shed a ray of light on the significance of dreams. It was also natural that, with this new basis of desire, sex should occupy the focal point of the system and that a new vocabulary of “Freudian” words should arise, among them “complex, inhibition, neurosis, psychosis, repression, resistance and transference.”

The early critics of Freud’s theories were filled with violent prejudice and moral indignation and sought to tear to pieces his entire system. The later critics acknowledged many of his theories to be valuable and devoted themselves to critical studies of his plan with a view to perfection rather than destruction. Dr. Freud himself believed that his ideas were harmed by their excessive popularity, which led to a reckless use of his theory and an exaggeration of his doctrines.

Although known as a Viennese, Dr. Freud was a Moravian by birth. He was born in this old Austro-Hungarian province on May 6, 1856, in the town of Freiberg. His parents moved to Vienna while he was young and he took his degree of Doctor of Medicine at the university there in 1881. After his graduation he served in turn as demonstrator in the physiological institute, Vienna, assistant physician in the general hospital, and lecturer on nervous diseases.

After becoming intensely interested in psychiatry he went on to Paris in 1885 to study in the famous school of [Jean-Martin] Charcot and [Pierre] Janet, known as the founders of modern abnormal psychology. He plunged into a wholly new investigation of neurotic disorders and developed a method so new that he made Janet one of his bitterest professional enemies. Several of Dr. Freud’s pupils in turn, among them C. G. Jung and Alfred Adler, diverged from him as widely as he did from his own teachers.

In forming his ideas about psychoanalysis Freud proceeded with an independence and uncompromising attitude which served either to alienate his associates completely or to win them over as virtual disciples.

After remaining in Paris a year he returned to Vienna, where he became a Professor Extraordinary of Neurology in 1902. He also used his apartment in Berggasse as a clinic and received daily many patients who came to him with all types and varieties of mental ailments. Later in life, age and illness forced him to cut down the number of his patients, but he continued to develop his theories and to write treatises on his chosen subject.

The Communist experiment in Russia was of great interest to the psychoanalyst, but the United States failed to attract him, even though he had visited this country in 1909, when he received an honorary degree from Clark University. Probably the only American whom he held in high esteem was William James, who he said was “one of the most charming men I have ever met.” Professor James, however, was to him the one exception in a country which has produced only “an unthinking optimism and a shallow philosophy of activity.”

The United States was scarcely more tolerant in many ways toward Dr. Freud, and many of his conceptions of this country were based on exaggerated or burlesqued writings on his principles. Probably the most predominant criticism in America of the Freudian theory is that the element of sex is grossly overplayed in his explanations of human actions and reactions.

Even the defenders of Dr. Freud have from time to time admitted that, like most specialists, he had carried many of his ideas too far and that he saw sex where its presence was debatable or even absent.

Dr. Freud was a prolific writer. His books have put before the world his wealth of ideas, startling and even sensational during the pre-war conservatism. His works on hysteria and the interpretation of dreams were probably his most widely known writings. In these he brought out the theory that hysteria is the result of a nervous shock, emotional and usually sexual in nature, and that the ideas involved have been suppressed or inhibited until they can no longer be recalled. By a use of the principle of psychoanalysis and the employment of the patient’s free-will associations these ideas can be recalled, he wrote, and the cause of the hysteria removed.

One of his outstanding works was an incidental writing which appeared near the close of the war, entitled “Reflections on War and Death.”

“The history of the world is essentially a series of race murders,” he wrote. “The individual does not believe in his own death. On the other hand, we recognize the death of strangers and of enemies, and sentence them to it just as willingly and unhesitatingly as primitive man did.”

Despite the ravages of cancer and infirmities of age, Dr. Freud continued to be active until after his 80th birthday on May 6, 1936. At that time, declining a request for an interview, he wrote: “What I had to tell the world I have told. I place the last period after my work.”

Many who had been the bitterest critics of his psychoanalysis theories gathered in Vienna on his 80th birthday to do him honor. He himself was not there, but his wife and family were, and they wept as Dr. Julius Wagneur-Jauregg, president of the Viennese Psychiatrists Association, said in opening the meeting:

“Viennese psychiatrists followed the trail blazed by Freud to worldwide fame and greatness. We are proud and happy to congratulate him as one of the great figures of the Viennese school of medicine.”

He still received a few patients after 1930, but most of the questioning was done by his daughter Anna, whom he recognized as his successor, the bearded, stoop-shouldered doctor merely nodding agreement from time to time. He received only a few old friends, who called on Wednesday nights to talk and on Fridays to play cards.

His last years also were disturbed by the pogroms against the Jews. When his books were burned by the Nazis in the bonfire which also consumed the works of Heine and other non-Aryan authors, he remarked, “Well, at least I have been burned in good company.”

Although egotistical in his professional contacts—he told the story that a peasant woman had told his mother when he was born that she had given birth to a great man—Freud was described by his family and his friends as gentle and considerate, a delightful companion when not talking “shop.”

Soon after his 81st birthday, when he was suffering from both cancer and a painful heart malady, he said despairingly, “It is tragic when a man outlives his body.”

During his last years, when he was to taste the bitterness of exile, Dr. Freud had been in retirement, engaged upon writing books. He had retired into his library and was seeking, in the few years left to him, to make a pioneering study of the nature of religion. As the annexation of Austria appeared more and more a menace, he was urged by his friends to seek refuge abroad, but he refused to go. If the Nazis invaded the refuge of his library, he told them, he was prepared to kill himself.

He was ill, a shadow of his former self at 82, when Nazi Germany moved her army into Austria and absorbed his homeland. He remained in seclusion in his five-room apartment, “dreading insults if he emerged—because he is a Jew,” friends said. A delegation of Netherlands admirers went to Vienna to offer him the hospitality of their country, but the authorities forbade him to go, refusing him a passport. Soon the reason was disclosed. The Nazis were demanding that he be ransomed.

A fund had been raised quietly by American admirers to pay his and his family’s living expenses once they left Vienna, but it was inadequate to meet the demand. Princess George of Greece, who as Princess Marie Bonaparte had studied under Freud, induced the Nazi authorities to accept a quarter million Austrian schillings to restore his passport.

In June, 1938, he was able to leave with his family and some personal books and papers. He went to Paris and then to London, the Nazi press sending after him a parting gibe, calling his school a “pornographic Jewish specialty.” Settling in London, he finished a book, “Moses and Monotheism,” a study of the Moses legend and its relation to the development of Judaism and Christianity.

The book, a first effort to use his psychoanalytic system to explain the origins of the institution of religion, aroused a storm of controversy. But it was hailed by Thomas Mann, who said it showed that the Freudian theory had become “a world movement embracing every possible field of learning and science,” as, for future generations, one of the most important foundation stones for “the dwelling of a freer and wiser humanity.”

In London Dr. Freud spent a contented year in a house a few hundred yards north of Regent’s Park. Leaving further development of his psychological theories to his daughter, Anna, and his disciples, he concentrated on his monumental study of the Old Testament, which he estimated would take him five years to complete.

He had stated its theme, that all religions only reflect the hopes and fears of man’s own deepest nature, in “Totem and Taboo” 25 years before, but now he sought to buttress his speculations with supporting evidence. This work, which he believed would have a far-reaching effect on religion, is now left uncompleted, it is believed.

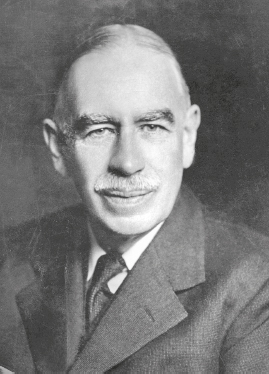

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES

June 5, 1883–April 21, 1946

LONDON—John Maynard Lord Keynes, the distinguished economist, whose work to restore the economic structure of a world twice shattered by war brought him worldwide influence, died of a heart attack today at his home in Firle, Sussex. He was 63.

Exhausted by the strain of the International Monetary Conference at Savannah, Ga., he returned to Britain a fortnight ago, tired and ill. Lady Keynes was with her husband at his death.

Noted as a political and social economist who influenced both specialists and the general public, Lord Keynes’s name was linked with that of Adam Smith. He was a protagonist of the theory that makes full employment the overriding aim of financial policy.

His genius expressed itself in many other spheres of activity. He was a Parliamentary orator of high order, a historian and devotee of music, drama and the ballet. A successful farmer, he was an expert on development of grass feeding stuffs. He also was a book collector, and his collection of unpublished Newton manuscripts on alchemy was noteworthy.

Lord Keynes at one period was the center of a literary circle that was known as “Bloomsbury”—Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf and their intimate friends.

Lord Keynes first won public attention through his resignation from the British Treasury’s mission to the Paris Peace Conference and his prediction that the Treaty of Versailles would prove more harmful to the nations dictating it than to Germany. His reasons were set forth in his 1919 book, “The Economic Consequences of the Peace,” which included his premise that the reparations clauses were too severe.

The book created a storm of controversy but was so widely in demand that it ran five editions the first year and was translated into eleven languages. Lord Keynes was not again associated with the British Government in any official capacity until the spring of 1940, by which time much of what he had prophesied had come true.

His place in economics and finance was formally recognized in 1942 with publication of the King’s Birthday Honors naming him first Baron of Tilton.

Lord Keynes had participated in the first meeting of the governors of the World Bank and Fund, set up under the Bretton Woods agreements, in Savannah, and was elected a vice president of the World Bank and Fund.

Born on June 5, 1883, in Cambridge, Lord Keynes entered government service at the age of 23, but continued his association with Cambridge University throughout his life and became High Steward of the city of Cambridge. His father, John Neville Keynes, was Registrary Emeritus of the university and his mother was a one-time Mayor of Cambridge.

Lord Keynes’s first position was as a minor official in the Revenue Department of the India Office, where he remained two years, then returned to Cambridge to teach and in 1912 became editor of The Economic Journal, a post he held throughout his life.

In 1915 he joined the Treasury Department, remaining until his resignation. In 1913–14 he had served as a member of the Royal Commission on Indian Finance and Currency.

His official designation at the peace conference was as the principal representative of the Treasury and Deputy for the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the Supreme Economic Council.

The sensation created by “The Economic Consequences of the Peace” was due in large part to its lucid literary style and its revelation of the inside story of the Paris conference.

Referring to that period, Kingsley Martin, editor of The New Statesman and Nation, a British publication, wrote: “Those who knew nothing of economics could appreciate, if only from quotations in the press, Mr. Keynes’ brilliant picture of M. Clemenceau, Mr. Lloyd George and President Wilson at Versailles.”

“It convinced us all that, whatever the other merits or evils of the treaty, its real vice was its failure to treat Europe as an economic whole and to reconstruct it for the benefit of the common people,” Mr. Martin continued. “It was a treaty of strategy and national greediness—with the League of Nations thrown in to make it look pretty.”

Lord Keynes’s theories about why the treaty would fail were largely reflected in his sketches of the principal participants in the conference.

He described M. Clemenceau as “by far the most eminent member of the Council of Four,” who alone knew “what he wanted—namely, to cripple Germany.” He claimed that President Wilson lacked the intellectual equipment to match wits with either Clemenceau or Lloyd George in the give-and-take of the conference table.

His characterization of the principals was summed up as follows:

“Clemenceau, aesthetically the noblest; the President, morally the most admirable; Lloyd George, intellectually the subtlest. Out of their disparities and weaknesses the treaty was born, child of the least worthy attributes of each of its parents, without nobility, without morality, without intellect.”

The book in a certain sense was the turning point in Lord Keynes’s career. Thereafter he was no longer a mere economist but a prophet and pamphleteer, a journalist and the author of a best seller.

Although contemptuous of Wilson, Lord Keynes was lavish in his praise of President [Franklin D.] Roosevelt. He sought, without success, to get the British Government to launch a spending program similar to that which President Roosevelt had established in the United States. He asked for a $500 million-a-year employment fund to provide for 500,000 men, a $500 million housing plan and a $500 million public works fund.

Frequently when Britain has been faced with a perplexing financial issue, Lord Keynes’s advice had been relied on heavily.

As a forerunner to matters taken up at Bretton Woods, N.H., in July, 1944, a White Paper, authored a year earlier by Lord Keynes and issued by the British Government, outlined a plan for a banking system between nations similar to a banking system within a nation.

He took a leading role in helping to crystallize the ideas for a world bank and stabilization of international currency at the monetary conference at Bretton Woods.

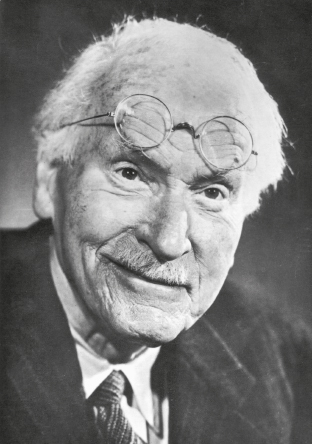

CARL JUNG

July 26, 1875–June 6, 1961

ZURICH—Professor Carl Gustav Jung, one of the founders of analytic psychology, died today at his villa in Kuessnacht on Lake Lucerne. The famed psychologist, who was beset by heart and circulatory troubles, was 85.

—The Associated Press

Dr. Jung was one of the great modern adventurers who sought to push back the dark frontiers of man’s mind.

Before the coming of his great forerunner, Dr. Sigmund Freud, the world was little used to rummaging through man’s subconscious to find the key to his peace and security. Before Freud and Jung, the Western world was inclined to think of man’s conduct in terms of original sin. Dr. Jung was one of those who gave a tremendous impetus to 20th-century thinking by declaring that this explanation was not good enough.

To bring some definition to the subconscious mind, Dr. Jung created special terms that soon became part of the language of the educated. Jungian terms such as extrovert and introvert became dinner-conversation clichés.

After an early apprenticeship, Dr. Jung broke with the harsh psychological school established by Freud. Freud held that nearly all human mental troubles were the result of sexual conflicts in infancy, the most powerful being the infantile urge to parricide and incest—the Oedipus and Electra complexes.

While admitting this urge, Dr. Jung said that man’s natural instinct toward religion was perhaps as strong as his sexual instinct.

Dr. Freud traced religion to the child’s helplessness before the outer world and the child’s need to cling to its parents in order to survive.

The Freudian world was a gloomy jungle in which man was forever stumbling over repressed emotional experiences. Freud and those who formed the hard core of his school believed that the only cure for man’s dilemma was to locate and remove these stumbling-block emotional experiences.

Dr. Jung, by contrast, held that man was not necessarily doomed to be buffeted by traumas over which he could exercise little control. The Jungians derided the Freudian theory that God was nothing more than man’s self-created vision of his father, and that good deeds and a desire to advance in the world were only devices to forget more primitive urges.

Freud’s world was found by many to be almost hopeless. Dr. Jung’s world was not exactly cozy, but he believed that man’s unconquerable spirit could make it better. Man could do this, Dr. Jung taught, because, in addition to the experiences of each individual, as registered in his subconscious mind, each person had a second group of experiences. This group was the collective experience of the race recorded in his subconscious mind, a collective experience that included man’s never-ceasing urge toward religion.

Freud, Dr. Jung and Dr. Alfred Adler were the three great figures in the age of psychology. They influenced Western man’s thinking as it had not been influenced since the publication of the “Origin of Species” in 1859. Adler, who likewise broke with the harsher theories of Freud, died in 1937, and Freud died two years later.

Dr. Jung was born on July 26, 1875, in Kesswil, Switzerland. He was a son of Paul Jung, an Evangelical minister, and Emille Freiswerk Jung. The family moved to Basel, where the son obtained a medical degree in 1900.

Dr. Jung became a lecturer in psychiatry at the University of Zurich and with Dr. Eugen Bleuler, founded the “Zurich School” of depth psychology. This school came to be thought of as opposing the “Vienna School” established by Dr. Freud, although Drs. Jung and Freud agreed about many basic tenets of modern psychology.

The methods used by Dr. Jung in obtaining the cooperation of the nonconscious factors in the mind were similar to those used by Freud.

In 1909 some of the best work in the United States in this field was being done at Clark University in Worcester, Mass., and in 1909 Dr. Jung, Dr. Freud and other world authorities on psychiatry went to Clark for a series of lectures and conferences. Here Dr. Jung gave his first extensive exposition of his “association method,” a hitherto untried method of probing the subconscious mind.

In 1911 Dr. Jung and other authorities in his field founded the International Psychoanalytic Society. Dr. Jung used this society to further his views on new elements that he believed he had found in dreams and fantasies.

Critics of Dr. Jung’s theories attacked him for showing too much interest in such unscientific matters as occultism and witchcraft. The Freudians held that he was betraying pure scientific research by digressions into Buddhism and Christianity. At this period, Dr. Jung also explored yoga, alchemy, folklore and tribal religious rites. All this was seen by his opponents as a betrayal of scientific principles.

Dr. Jung said that, on the contrary, since mankind had devoted so much thought to such matters, they formed part of man’s consciousness of the race.

During Hitler’s ascendency in Germany, Dr. Jung’s theories about the consciousness of the race were borrowed by the Nazis. Dr. Jung hastened to say that the Nazi interpretation of his theories was largely wrong and his statements in this matter had been distorted out of their true meaning by Hitler’s followers.

In 1948, the C. G. Jung Institute was established in Zurich to provide scholars with a place to do advanced research in analytical psychology.

Although Dr. Freud and Dr. Jung differed on many of the fundamentals of applied psychology, they remained friendly and once talked nonstop for 12 hours. Each would tell the other his dreams and they would give their interpretations of their findings.

The two great explorers of the mind differed in their methods of obtaining their material. Dr. Freud established the now generally accepted method of placing his subject on a couch and withdrawing himself to create the impression on the subject that he was not intruding. Dr. Jung usually placed his subject in a chair opposite him and made him feel that he, Dr. Jung, would share his subject’s experiences with him.

In 1903 Dr. Jung married Emma Rauschenbush, heiress to a Swiss watch fortune, who died in 1955. He is survived by a son and four daughters.

Dr. Jung was a tall, large-boned man who in his later years had a scraggly white mustache and thinning white hair. He had a ruddy complexion and a crinkly and charming smile.

Over the door of his home in Kuessnacht is carved the Latin inscription:

Vocatus atqua non vocatus deus aderit. (Called or not called, God is present.)

KARL BARTH

May 10, 1886–December 10, 1968

By Edward B. Fiske

Karl Barth, the Protestant theologian, died in his sleep Monday night at his home in Basel, Switzerland, a family spokesman announced yesterday. He was 82 years old.

In 1919 an unknown Swiss country pastor gave the world a rather unpretentious-sounding book entitled “The Epistle to the Romans.” He had had difficulty finding a publisher, but, as a fellow theologian later put it, the volume “landed like a bombshell in the playground of the theologians.”

The young pastor was Karl Barth, and his commentary on Romans was one of those events that happen only rarely in a discipline such as theology—when a revolutionary idea falls into the hands of a giant who possesses the powers not only to utter it but also to control its destiny.

In this case the idea was the radical transcendence of God. At a time when theologians had reduced God to little more than a projection of man’s highest impulses, Dr. Barth rejected all that human disciplines such as history or philosophy could say about God and man. He spoke of God as the “wholly other” who entered human history at the moments of His own choosing and sat in judgment on any attempt by men to create a God in their own image.

Forty years later Dr. Barth (rhymes with “heart”) was to apply a “corrective” to this radical distinction between God and man. In the meantime, he would produce one of the monuments of 20th-century scholarship, “Church Dogmatics,” and come to be widely regarded as the most important Protestant theologian since John Calvin. He was frequently compared with Augustine, Anselm and Martin Luther.

Dr. Barth’s conclusions were sometimes radical; but his language was traditional, and it was the classic dogmas of the church that excited his imagination. His overriding concern was to spell out in large, bold letters the grand Trinitarian themes of the Christian faith.

Largely because of this he came to have as much influence in the Roman Catholic community as any contemporary Protestant thinker.

Years after the appearance of the commentary that made him into a major theological figure, Dr. Barth likened himself to “one who, ascending the dark staircase of a church tower and trying to steady himself, reached for the banister, but got hold of the bell rope instead.

“To his horror, he had then to listen to what the great bell has sounded over him and not over him alone.”

Liberal theology of the 19th century had started out as a protest against the sterile dogmatism and Biblical literalism into which Protestant thought had degenerated in the centuries following the Reformation.

In contrast to Luther, who was preoccupied with the sinfulness and helplessness of man before a just God, liberal theologians emphasized reason, the scientific method and the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth.

By the turn of the 20th century, however, such thinking had itself become sterile.

Ludwig Feuerbach had reduced theology to anthropology, and the “queen of the sciences” came to be measured not by its own standards but by those of philosophy, natural science and history. Jesus took on all the attributes of a European gentleman.

The man who rang in a new theological era was as Swiss as cheese fondue. Dr. Barth was rather tall, with a high forehead and cheekbones, craggy eyebrows and pale blue eyes. In his later years he looked like a casting agency’s idea of a German professor—with a shock of wayward gray hair and horn-rimmed glasses that usually sat at the tip of his nose. His physique was rugged and showed the effects of much horseback riding and mountain climbing in his youth.

The ideas that led to “The Epistle to the Romans” were formed during a 10-year pastorate in Safenwil, a small village in north central Switzerland. Along with Eduard Thurneysen, a close friend who was pastor in a neighboring village, Dr. Barth began to entertain doubts about the tradition on which he had been reared.

The critical moments came in 1914, the year that hopes for establishing the Kingdom of God on earth were trampled into the European mud by the heels of marching troops.

The biggest shock occurred on what Dr. Barth later described as a “black day” in August when 93 German intellectuals, including almost all of his theological teachers, proclaimed their support of the war policy of Kaiser Wilhelm II. In “The Epistle to the Romans” in 1919 and in a completely revised second edition three years later, Dr. Barth set out, as he put it, “to turn the rudder [of theology] an angle of exactly 180 degrees.”

The marker on which he set his sights can be illustrated by a picture that hung above his desk during this period, Matthias Grunewald’s “Crucifixion.” Dominating the darkened landscape is the agonizing figure of Jesus on the Cross. Just as the composition of Grunewald’s painting sends the viewer’s eyes repeatedly back to the central figure, so Dr. Barth’s theology is built around the revelation of God in Jesus Christ.

The Scriptures, said Dr. Barth, contain “divine thoughts about men, not human thoughts about God.” He saw this as the cure for doctrinal errors that had led to the divisions within Christendom.

His fidelity to the Bible as the Word of God led him to reject Calvin’s idea that some men were “predestined” by God to eternal salvation or damnation. Dr. Barth once remarked, “Calvin is in Heaven and has had time to ponder where he went wrong. Doubtless he is pleased that I am setting him right.”

Dr. Barth’s views were the source of much controversy. Fundamentalists charged that despite his emphasis on the Bible, he had actually replaced the Scriptures with Christ as the ultimate authority for faith. He was also accused of being too rigid, and many maintained that his emphasis on the helplessness of man in the face of evil was too pessimistic.

If Dr. Barth was a revolutionary, his ideas were also deeply embedded in the traditions of the Calvinistic, or Reformed, branch of Protestantism. Many Barths before him, including his father, Fritz, had been Swiss Reformed pastors.

He was born May 10, 1886, in Basel, where his father had a church. When he was three, the family moved to Bern, where Fritz Barth had accepted a post as professor of New Testament and church history at the university. It was there that Karl, the oldest of five children, was reared and educated and acquired the local Swiss German dialect that caused German purists to shudder.

He began studying theology in 1904 at the age of 18 under his father, and was ordained in 1908. After a year as assistant to the editor of a liberal theological journal, he took his first pastorate in Geneva. Two years later he moved to Safenwil, where he first revealed his penchant for political debate that later led to his confrontation with the Third Reich and an international dispute over his attitude toward Communism.

Dr. Barth became a religious socialist and in 1915 joined the Social Democratic party.

Following the publication of “The Epistle to the Romans,” Dr. Barth accepted in September, 1921, a post as professor of Reformed theology at the University of Gottingen. By 1927 his theological ideas had crystallized sufficiently for him to publish “The Doctrine of the Word of God: Prolegomena to Christian Dogmatics.” He soon came to regard this work as an unsuccessful experiment, however, and repudiated it.

In 1930 Dr. Barth became professor of systematic theology at Bonn. It was there, in 1932, that he published the first half-volume of “Church Dogmatics.” This exposition of his theological thinking eventually grew to more than 6 million words on 7,000 pages in 12 volumes. It still lacked several volumes when he retired in 1962 and abandoned the project.

Dr. Barth was willing to reverse himself at times, and he insisted that even his own “Church Dogmatics” was tentative and written only to be revised and refined by his students.

His confrontation with the Third Reich began in the summer of 1933, when Hitler started to establish “German Christian” churches in which National Socialist teachings were given dogmatic status. He refused to take the oath of allegiance that Hitler required of state employes or to begin his lectures with a salutation to the Fuehrer.

In 1934 about 200 leaders of German Protestantism signed the Barmen Confession, which asserted the freedom of the church from temporal powers. Dr. Barth was the chief author.

He was soon convicted by a Nazi court of “seducing the minds” of his students and was suspended from his teaching position. In October, 1935, he was escorted to the Swiss border at Basel and expelled from Germany.

After the war this outspoken critic of Nazism became a controversial defender of the German people. He visited Germany in 1945 and in the next two years spent two semesters teaching in Bonn.

In 1948 Dr. Barth visited Hungary, and in the years following he drew bitter criticism for his refusal to attack Communism with the same vigor with which he had protested Nazism. He regarded Communism, too, as idolatrous, but he saw it as the “natural result” of the failure of Western culture to solve some of its human problems.

After his retirement in 1962 at the age of 75, Dr. Barth surprised everyone by undertaking a trip to the United States, where his son Markus was a professor of New Testament at the University of Chicago. He gave a number of lectures, but the highlights of the visit for him were trips to the Civil War battlefields at Gettysburg and Richmond.

From childhood Dr. Barth’s hobby had been military history, and he carried in his head the names of all the generals and battles of the Napoleonic and other wars. In later years he became an American Civil War buff.

Despite an ascetic workday that for years lasted from regular 7 A.M. lectures to post-midnight writing and study, he was always willing to take time out to play tin soldiers with his sons. “Dad had a collection of hundreds of soldiers,” Markus said, “and he always insisted on being Napoleon. So he always won.”

Dr. Barth was proud that two of his sons followed him into the field of theology. Markus, the eldest, now teaches at the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, while Christop is a professor of Old Testament in Mainz, West Germany. A daughter, Franziska, is married to a businessman in Basel, where the third son, Hans Jakob, is a landscape architect. A fourth son died in a mountain-climbing accident.

Their mother, the former Nell Hoffman, was a violin student whom Dr. Barth married in 1913.

REINHOLD NIEBUHR

June 21, 1892–June 1, 1971

By Alden Whitman

The Rev. Reinhold Niebuhr, the Protestant theologian who had wide influence in the worlds of religion and politics, died last evening at his summer home in Stockbridge, Mass., after a long illness. He was 78 years old.

Throughout his long career he was a theologian who preached in the marketplace, a philosopher of ethics who applied his belief to everyday moral predicaments and a political liberal who subscribed to a hard-boiled pragmatism.

Combining all these capacities, he was the architect of a complex philosophy based on the fallibility of man and the absurdity of human pretensions, as well as on the Biblical precepts that man should love God and his neighbor.

The Protestant theology that Mr. Niebuhr evolved over a lifetime was called neo-orthodoxy. It stressed original sin, which Mr. Niebuhr defined as pride, the “universality of self-regard in everybody’s motives, whether they are idealists or realists or whether they are benevolent or not.”

It rejected utopianism, the belief “that increasing reason, increasing education, increasing technical conquests of nature make for moral progress, that historical development means moral progress.”

Reinhold Niebuhr was the mentor of scores of men, including Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who were the brain trust of the Democratic party in the nineteen-fifties and sixties. George F. Kennan, the diplomat and adviser to Presidents on Soviet affairs, called Mr. Niebuhr “the father of us all” in recognition of his role in encouraging intellectuals to help shape national policies.

“The finest task of achieving justice,” Mr. Niebuhr once wrote, “will be done neither by the Utopians who dream dreams of perfect brotherhood nor yet by the cynics who believe that the self-interest of nations cannot be overcome. It must be done by the realists who understand that nations are selfish and will be so till the end of history, but that none of us, no matter how selfish we may be, can be only selfish.”

Mr. Niebuhr was himself active in politics, as a member first of the Socialist party, and then as vice chairman of the Liberal party in New York.

He was an officer of Americans for Democratic Action and active in numerous committees established to deal with specific social, economic and political matters. He was a firm interventionist in the years before United States entry into World War II. He was equally firm in opposing Communist goals after the war, but at the same time he was against harassing American Communists.

Much of Mr. Niebuhr’s political influence was embodied in an outpouring of articles on topics ranging from the moral basis of politics to race relations to pacifism to trade unionism to foreign affairs.

Mr. Niebuhr had been associated with Union Theological Seminary, Broadway and 121st Street, since 1928. Hundreds of seminarians jammed lecture halls for his courses, and thousands of laymen heard him preach or lecture. He spoke at many colleges, preached at scores of churches and appeared on innumerable public platforms.

Mr. Niebuhr possessed a deep voice and large blue eyes. He used his arms as though he were an orchestra conductor. He wore his erudition lightly and spoke in common accents. When he preached, one auditor recalled, “he always seemed the small-town parish minister.”

He looked outsized in his snug office on the seventh floor of the seminary. Its walls were so hidden by books, mostly on sociology and economics, that there was space for only one picture, a wood engraving of Jonah inside the whale. On his desk, amid a wild miscellany of papers, was a framed photograph of his wife, Ursula, and his son and daughter, who survive him.

When students dropped in, he liked to rock back in his swivel chair, cross his legs, link his hands on top of his head and chat. Mr. Niebuhr was “Reinie” to friends and acquaintances. His highest earned academic degree was Master of Arts, which he received from Yale in 1915, but he collected 18 honorary doctorates, including a Doctor of Divinity from Oxford.

For several years in the nineteen-thirties he edited and contributed to The World Tomorrow, a Socialist party organ; from the forties he edited and wrote for Christianity and Crisis, a biweekly magazine devoted to religious matters. In an ecumenical spirit, he wrote for The Commonweal, a Roman Catholic magazine; for Advance and Christian Century, Protestant publications; and for Commentary, a Jewish publication.

Because Mr. Niebuhr did not employ Biblical citations to support his political attitudes, some associates were skeptical of the depth of his faith.

“Don’t tell me Reinie takes that God business seriously,” a political co-worker once said.

The remark got back to Mr. Niebuhr, who laughed and said: “I know. Some of my friends think I teach Christian ethics as a sort of front to make my politics respectable.”

Troubled agnostics, Catholics, Protestants and Jews often came to him for spiritual guidance. Only half facetiously, one Jew confessed: “Reinie is my rabbi.”

Among Mr. Niebuhr’s admirers was Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. After listening to one sermon, the late Justice said:

“I liked what you said, Reinie, and I speak as a believing unbeliever.”

“I’m glad you did,” the clergyman replied, “for I spoke as an unbelieving believer.”

Although Mr. Niebuhr was acclaimed as a theologian, the closest he came to systematizing his views was in his two-volume “The Nature and Destiny of Man,” published in 1943. He began an “intellectual biography” issued in 1956 by saying:

“I cannot and do not claim to be a theologian. I have taught Christian Social Ethics for a quarter of a century and have also dealt in the ancillary field of apologetics. My avocational interest as a kind of circuit rider in colleges and universities has prompted an interest in the defense and justification of the Christian faith in a secular age…

“I have never been very competent in the nice points of pure theology; and I must confess that I have not been sufficiently interested heretofore to acquire the competence.”

There was, nonetheless, a Niebuhr doctrine. In its essence it accepted God and contended that man knows Him chiefly through Christ, or what Mr. Niebuhr called “the Christ event.” The doctrine, in its evolved form, suggested that man’s condition was inherently sinful, and that his original, and largely ineradicable, sin is his pride, or egotism.

He argued also that man deluded himself most of the time; for example, he believed that a man who trumpeted his own tolerance was likely to be full of concealed prejudices and bigotries.

“The Christian faith cannot deny that our acts may be influenced by heredity, environment and the actions of others,” he once wrote. “But it must deny that we can ever excuse our actions by attributing them to the fault of others, even though there has been a strong inclination to do this since Adam excused himself by the words, ‘The woman gave me the apple.’”

Mr. Niebuhr also insisted that “when the Bible speaks of man being made in the image of God, it means that he is a free spirit as well as a creature; and that as a spirit he is finally responsible to God.”

Billy Graham, the evangelist, and the Rev. Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, the expositor of “the power of positive thinking,” were among the clergymen Mr. Niebuhr contradicted. Their “wholly individualistic conceptions of sin,” he said, were “almost completely irrelevant” to the collective problems of the nuclear age.

Mr. Niebuhr objected especially to the notion that religious conversion could cure race prejudice, economic injustice or political chicanery. The remedy, he believed, lay in societal changes spurred by Christian realism.

Reinhold Niebuhr was born June 21, 1892, in Wright City, Mo., the son of Gustav and Lydia Niebuhr. His father was pastor of the Evangelical Synod Church, a German Lutheran congregation, in that farm community. At the age of 10 Reinhold decided that he wanted to be a minister because, as he told his father, “you’re the most interesting man in town.” At that point his father set about teaching him Greek.

From high school Reinhold went, with his brother Richard, to Elmhurst College in Illinois, a small denominational school, and from there, after four years, to Eden Theological Seminary, near St. Louis. After the death of his father in 1913, Reinhold was asked to take his pulpit in Lincoln, Ill. He declined in order to enter Yale Divinity School on a scholarship. He received his Bachelor of Divinity degree there in 1914, and his Master of Arts a year later.

Mr. Niebuhr was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964.

Upon his ordination by the Evangelical Synod of North America, he was sent to his first and only pastorate, the Bethel Evangelical Church of Detroit. He remained there 13 years, nurturing the congregation from 20 members to 650, and becoming the center of swirling controversy for his support of labor, and later for his espousal of pacifism.

“I cut my eyeteeth fighting Ford,” Mr. Niebuhr said. Whereas Henry Ford was usually praised in those days for his wage of $5 a day and the low price of his automobiles, he was condemned by Mr. Niebuhr as ravaging his workers by the assembly line, the speedup, periodic layoffs and dismissal of men in middle age.

“Mr. Ford typified for my rather immature social imagination all that was wrong with American capitalism,” Mr. Niebuhr said years later. “I became a Socialist in this reaction. I became a Socialist in theory long before I enrolled in the Socialist party and before I had read anything by Karl Marx.”

For years Mr. Niebuhr preached what was termed “the social Gospel,” a jeremiad against the abuse of laissez faire industrialism. He was a founder, in 1930, of the Fellowship of Socialist Christians.

“Capitalism is dying and it ought to die,” he said in 1933, when he was agitating for the Socialist party. Yet even then he was reassessing his beliefs. He had never been a thoroughgoing Marxist, an advocate of class struggle and revolution. His ultimate break with socialism was on religious and ethical grounds, and later on realistic grounds. It was idolatry, he thought, to suggest that human beings could bring forth the Kingdom of God on earth.

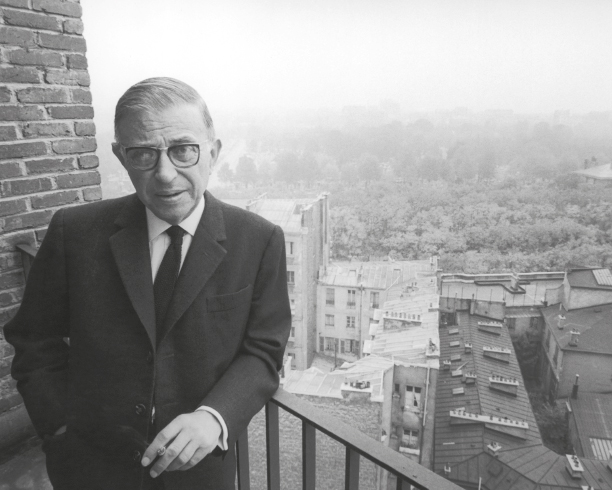

JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

June 21, 1905–April 15, 1980

By Alden Whitman

Jean-Paul Sartre, whose existentialist philosophy influenced two generations of writers and thinkers throughout the world, died of edema of the lung yesterday in Paris. He was 74 years old.

Long regarded as one of France’s reigning intellectuals, Mr. Sartre contributed profoundly to the social consciousness of the post–World War II generation through his leftward political commitments, which took him away from his desk and into the streets. He had ideas on virtually every subject, which were developed in novels, plays, biographies, essays and tracts.

Mr. Sartre’s points of view were less heeded in the 1970’s as he became a maverick political outsider on the extreme left. His last substantial work was a biography of the 19th-century French novelist Gustave Flaubert.

Although Mr. Sartre was once closely allied with the Communist Party, he was for the last 15 years an independent revolutionary who spoke more in the accents of Maoism than of Soviet Communism. As an intellectual and a public figure, he used his prestige to defend the rights of ultra-leftist groups to express themselves, and in 1973 he became titular editor of Liberation, a radical Paris daily. In addition, he lent his name to manifestos and open letters in favor of repressed groups in Greece, Chile and Spain. He was a rebel with a thousand causes, a modern Don Quixote.

Twenty-five years ago Mr. Sartre, with Albert Camus and a few others, was an iridescent intellectual leader. But in recent times his stature was that of an ancestor figure whose generative conceptions had lost their force.

It was fashionable to say that his lasting contribution would be his plays, implying that his essays and novels would not survive. As a philosopher he was increasingly criticized for his unsystematic approach. Nonetheless, few denied him respect for his continued attempts to live his ideas, often at the cost of ridicule.

“I have put myself on the line in various actions,” Mr. Sartre said several years ago. He had in mind his activity against the Gaullist regime and his sometimes lonely protests against the American involvement in Vietnam.

Much earlier in his career as a freewheeling leftist, during the Nazi occupation of France, Mr. Sartre had, he said, “indeed worked with the Communists, as did all Resistants who were anti-Fascist.” His support lasted until the Hungarian uprising of 1956 and the intervention by Russian troops. “The French Communist Party supported the invasion of Hungary, so I broke with it,” he explained. After backing the Algerian nationalists in their struggles with France, he moved steadily more leftward, and after the French demonstrations and street fighting of May 1968 he was an active militant.

He was arrested for ultra-leftist causes, and his voice became more strident. “The task of the intellectual is not to decide where there are battles but to join them wherever and whenever the people wage them,” he said. “Commitment is an act, not a word.”

His sense of commitment precluded homage. He rejected the Nobel Prize in Literature, awarded him in 1964, on the ground that he did not wish to be “transformed into an institution.”

Mr. Sartre’s philosophical views developed and shifted. In “Words,” the story of his youth published in the mid-60’s, he criticized the social, philosophical and literary ideas with which he had been raised. Commenting on his autobiographical novel “Nausea” and his philosophical work “Being and Nothingness,” he said that an attitude of aristocratic idealism lay behind their composition, which he now rejected. The core of his existentialism, however, was not condemned. Roughly expressed, this suggests that “man makes himself” despite his “contingency” in an “absurd world.”

His existentialism seemed to express a widespread disillusionment with fixed ideas amid the revolutionary changes that flowed from World War II. Out of this existentialism came such diverse manifestations as the anti-novel, the anti-hero, and the notion of man’s anguished consciousness. Also implicit in it was a call to action, in which man could assume some control of his destiny.

This was a far different set of values from those into which Jean-Paul Sartre was born in Paris on June 21, 1905. His father, Jean-Baptiste, was a naval officer who died shortly after his son’s birth. His mother, Anne-Marie Schweitzer, was a cousin of Albert Schweitzer.

As Mr. Sartre described himself, he was an ugly “toad” of a boy, without friends his age. By pretending to read, he learned to read before he was 4. By plagiarizing, he learned how to write stories, a process that hastened his retreat from life into words, more real than the objects they denoted.

He became a very good student, and he entered the elite Ecole Normale Superieure when he was 20. There he began his lifelong companionship with Simone de Beauvoir, a fellow student who would become his longtime companion, with an agreement pledging mutual loyalty in times of need but allowing “contingent loves.”

After taking a degree, he went to Germany in 1933 to study under Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, two of the most influential European philosophers, interested in the nature of being and reality and the mysteries of perception.

Mr. Sartre’s ideas were summed up by Frank Kappler, an American writer who, after quoting Mr. Sartre’s famous formula—“Existence precedes essence”—wrote:

“Man comes into a totally opaque, undifferentiated, meaningless universe. By the power of his mysterious consciousness, which Sartre calls unmeant, man makes of the universe a habitable world. Whatever meaning and value the world has comes from his existential choice. These choices differ from one to another.

“Each lives in his own world, or, as Sartre also says, each creates his own situation. Frequently this existential choice is buried in a lower level of consciousness. But to become truly alive, one must become aware of oneself as an ‘I’—that is, a true existential subject, who must bear alone the responsibility for his own situation.”

In this predicament, Mr. Sartre believed, one can choose an “inauthentic existence,” or one can commit oneself by a resolute act of free choice to a positive role in human affairs. Most of these ideas are elaborated in “Being and Nothingness,” which he wrote during the Nazi occupation of France. In 1938, he had published “Nausea,” a novel in which a character named Antoine Roquentin was seized with the horrors of existentialism while meditating in a public park.

The novel ends when Roquentin decides that if he can only create something, a novel perhaps, his creativity could mean engagement. The central character was almost certainly the author.

By the end of World War II, Mr. Sartre was well known in France for both his writings and his activity in the Resistance. His philosophy suited many of the younger generation of students, who saw in existentialism an opportunity for salvation through commitment to a “new” French culture.

Mr. Sartre and his disciples at first gathered at the Cafe de Flore on Paris’s Left Bank. As the group grew, they moved to the roomier Cafe Pont-Royal.

After doing two plays during the war, including “No Exit,” Mr. Sartre busied himself with the theater in a number of dramas of ideas. Mr. Sartre was also writing biographies of Baudelaire, the 19th-century poet, and Jean Genet, a writer with a long criminal record. Parts of these and other of his writings were published in Les Temps Modernes, his monthly review founded in 1945.

Mr. Sartre, a short, wall-eyed man who always seemed in a fury of creativity, lived simply, with few possessions other than his books, in a small apartment on the Left Bank. And although he betrayed a certain amiability, he remained until the end an angry man.

“As far as the state of French politics goes, I don’t see a lot I can do,” he wrote. “It’s so rotten what’s happening in France now! And there’s no hope in the immediate future; no party offers any hope at all.”

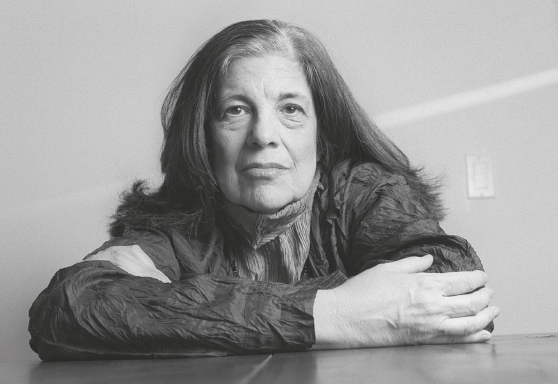

SUSAN SONTAG

January 16, 1933–December 28, 2004

By Margalit Fox

Susan Sontag, the novelist, essayist and critic whose impassioned advocacy of the avant-garde and equally impassioned political pronouncements made her one of the most lionized and polarizing presences in 20th-century letters, died yesterday morning in Manhattan. She was 71.

The cause was complications of leukemia, her son, David Rieff, said. Ms. Sontag had been ill with cancer intermittently for the last 30 years, a struggle that informed one of her most famous books, the critical study “Illness as Metaphor.”

A highly visible public figure since the mid-1960’s, Ms. Sontag wrote four novels, dozens of essays and a volume of short stories and was also an occasional filmmaker, playwright and theater director. For four decades her work was part of the contemporary canon, discussed everywhere from graduate seminars to the pages of popular magazines.

Ms. Sontag gleefully blurred the boundaries between high and popular culture. She advocated an aesthetic approach to the study of culture, championing style over content. She was concerned with sensation, in both meanings of the term.