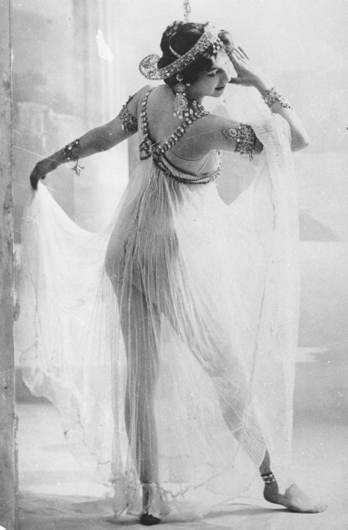

MATA-HARI

August 7, 1876–October 15, 1917

PARIS—Mata-Hari, the Dutch dancer and adventuress, who, two months ago, was found guilty by a court-martial on the charge of espionage, was shot at dawn this morning.

The condemned woman, otherwise known as Marguerite Gertrude Zelle, who was 41, was taken in an automobile from St. Lazaire prison to the parade ground at Vincennes, where the execution took place. Two sisters of Charity and a priest accompanied her.

Mlle. Mata-Hari, long known in Europe as a woman of great attractiveness and with a romantic history, was accused, according to press dispatches, of conveying to the Germans the secret of the construction of the Entente “tanks,” this resulting in the Germans rushing work on a special gas to combat their operations.

She was said to have left Paris last Spring and to have spent some time in the English town where the first “tanks” were being made, afterward traveling back and forth between England and Holland, and later going to Spain, where she aroused suspicion by associating with a man whom the French Secret Service had long suspected. When she reappeared in Paris she was arrested—a contributing circumstance, it appears, being the fact that she was seen there with a young British officer attached to the “tank” service.

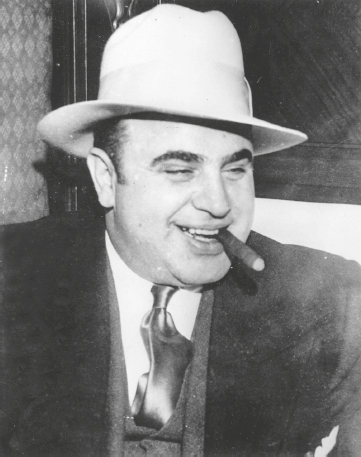

AL CAPONE

January 17, 1899–January 25, 1947

MIAMI BEACH, Fla.—Al Capone, ex-Chicago gangster and Prohibition era crime leader, died in his home here tonight.

“Death came very suddenly,” said Dr. Kenneth S. Phillips, who has been attending Capone since he was stricken with apoplexy Tuesday.

“All the family was present. His wife, Mae, collapsed and is in very serious condition.”

Dr. Phillips said death was caused by heart failure.

—The Associated Press

Alphonse (Scarface) Capone, the fat boy from Brooklyn, was a Horatio Alger hero—underworld version. More than any other one man, he represented, at the height of his power, from 1925 through 1931, the debauchery of the “dry” era. He seized and held in thrall during that period the great city of Chicago and its suburbs.

Head of the cruelest cutthroats in American history, he inspired gang wars in which more than 300 men died by the knife, the shotgun, the tommy gun and the pineapple, the gangster adaptation of the World War I hand grenade.

His infamy made international legend. In France, for example, he was “The One Who Is Scarred.” He was the symbol of the ultimate in American lawlessness.

Capone won great wealth; how much, no one will ever know, except that the figure was fantastic. He remained immune from prosecution for his multitudinous murders (including the St. Valentine Day Massacre in 1929, when his gunners, dressed as policemen, trapped and killed eight of the Bugs Moran bootleg outfit in a Chicago garage), but was brought to book, finally, on the comparatively sissy charge of evasion of income taxes amounting to around $215,000.

For this, he was sentenced to 11 years in Federal prison—serving first at Atlanta, then on The Rock, at Alcatraz—and was fined $50,000, with $20,000 additional for costs. With time out for good conduct, he finished this sentence in mid-January of 1939; but by then he was a slack-jawed paretic overcome by social disease, and paralytic to boot.

Capone was born in Naples on Jan. 17, 1899, the son of an impoverished barber. The family moved to New York and settled in the Mulberry Bend district near the Brooklyn Bridge. Here, after he quit school in the fourth grade to knock about the streets, he met Johnny Torrio, whom he was to succeed, many years later, as head of the bootleg and vice syndicate in Chicago.

The parents, devout people, moved to South Brooklyn, and Al, barely out of his teens, one day bullied one of the neighbors, an undersized, quick-tempered Sicilian, in a Fourth Avenue barber shop. His victim backed Capone into a corner and slashed him twice with a razor. He and Capone never crossed trails again, nor did Capone, on his infrequent visits to the old neighborhood after he reached great power, ever seek him out or order his destruction.

In 1910, John Torrio left the Five Points and Mulberry Bend to try his evil genius in Chicago. The advent of Prohibition in 1920 saw great expansion of the Torrio interests. He took to bootlegging in a big way.

Torrio needed more men, tough men. He sent for the fat boy, and Capone took the next train for Chicago to join Torrio at $75 a week. This was big money for him at the time. He had managed to stay out of the World War because he didn’t like that type of fighting. Later he encouraged the legend that he had been a machine gunner in the AEF [American Expeditionary Forces], but this was Capone poppycock.

For three or four years after Capone’s arrival in Chicago, he served as a “rod,” or professional killer, for Torrio and at the same time proved himself unusually good at organizing the vice and bootleg phases of the Torrio chain.

Greed begets greater greed. Torrio wanted a hog’s share of the “take” and shortchanged his men. This resulted in a split, the opposition taking form under the leadership of Dion O’Banion, a murderous fellow who, paradoxically, had an inordinate love for flowers.

Most of his men were Irish; most of Torrio’s Italian, and the war took on a bitter racial angle. On Nov. 10, 1924, three Capone men walked into the florist shop opened by O’Banion more for a hobby than for profit. They riddled him with shot, and he fell back among his roses and carnations. Capone and Torrio attended the burial, sent loads of wreaths as a sentimental gesture and tried to look innocent.

Later in 1925, a gang caught up with Torrio and fired five shots into him. He decided, at this juncture, that he had had enough. He pulled out, and Capone was left in command.

Immediately Capone began a campaign of expansion. He established agents along the East Coast to handle his rum cargoes, he had men in Florida and in the Bahamas; he had men along the Canadian border. Capone caravans crisscrossed the nation with valuable loads of contraband to slake the thirst of the Middle West.

By the end of 1925, Capone was riding high. He had a magnificent home on Prairie Avenue, where he lived with his wife, Mae, and their Sonny, six years old. His brother Ralph (Bottles) Capone, was on his staff.

Word came to Chicago at this time that Peg-Leg Lonergan, head of the downtown Brooklyn waterfront bad men, was plaguing some of Capone’s old friends. Peg-Leg’s idea of sport was to lead a handful of longshoremen into the Adonis Social Club on 20th Street, near Fourth Avenue, and badger the Italian customers, all old neighbors of Capone’s.

The Adonis Club had sentimental attachments for Capone. In the cellar of the club, in his teens, he had perfected his pistol work by shooting at beer bottles. He was in the place on Christmas night, 1925, with five furtive-looking men-at-arms from Chicago, when Peg-Leg and his boisterous crew came in a-whooping.

At 3 o’clock the next morning, police of the Fifth Avenue station reached the club on the run, attracted by a fusillade of gunfire. Peg-Leg lay dead near the door; Aaron Harms and Needles Ferry, two of his pals, lay dead under the piano, staring with unseeing eyes at the orange, red and green paper twists that bedecked the ceilings and fixtures. A fourth Lonergan man crawled on the sidewalk, badly wounded.

Capone and eight other men, together with a couple of girl patrons of the Adonis Club, were rounded up. The fat man from Chicago, blazing with diamonds, assumed an air of injured innocence. He insisted that he had come all the way from the Windy City to pay a Christmas call on his mother and that he had merely happened to be in the nightclub when the shooting started.

He was turned out with the rest because all the other witnesses, like himself, related that they did not happen to be looking when the guns opened fire. Without witnesses the police had no case. Capone, having paid his Christmas call and having delivered three neat homicides as gifts, returned to Chicago.

Emboldened, Capone came out in the open to support Big Bill Thompson in 1929, in what was known as the “pineapple” primary. Opposition candidates were subject to all the little violent tricks in the Capone bag, including the tossing of this iron fruit. His men had shot and killed William McSwiggin, State’s Attorney for Cook County, and if they could get away with that (as they did) he felt he could get away with anything.

Before the pineapple primary, he had also staged the cruelest murder in the annals of American gangster crime. He had hired Fred (Killer) Burke of the Egan’s Rats, a St. Louis gang, to perform this particular job. The Killer dressed three of his men in police uniforms, walked in on seven Moran men in the SMC Cartage Company Garage on St. Valentine’s Day, 1929, and sprayed them with Thompson submachine guns and sawed-off shotguns until the last of the seven stopped twitching.

The Capone crowd lost the pineapple primary, in spite of terroristic tactics. Dissension, subsurface but sinister, got to work in the organization. The fat boy tried to stem it with a brutal show of power at a hotel banquet, where he brained the guests of honor—two defecting brothers who thought their plotting had been secret—with a baseball bat. He had also been warned of a double-cross by Frankie Uale, his Brooklyn agent, and Uale had been shot to death by Killer Burke and his crowd.

In May 1929, Capone surrendered to the police in Philadelphia to get a year’s peace from the increasing threat of the Moran guns. The charge in the Philadelphia case was carrying concealed weapons.

In October 1931, he went on trial for income-tax evasion, guarded in the Federal court chamber by one of his own men. An attendant spotted the bodyguard’s shoulder holster, and the thug was sentenced for contempt.

Capone’s highly paid counsel tried to persuade a grim-lipped jury that their client was a persecuted man. The plea fell on deaf ears. When Judge Wilkerson pronounced sentence, the fat man’s face went dark and the ugly scar went white.

Capone entered Atlanta penitentiary on May 5, 1932. In August 1934, he was chained and fettered and taken to forbidding Alcatraz. This was the beginning of the end for America’s “Public Enemy Number One,” a title in which he had gloried.

In February 1938, he became violent. Word came out of Alcatraz that the prison doctors had decided that the great Capone was done; “subject to intermittent mental disturbances.”

In November 1939, Capone was released from prison and admitted to the Union Memorial Hospital in Baltimore to take treatment for paresis. Later he settled at Miami Beach.

ETHEL ROSENBERG

September 28, 1915–June 19, 1953

JULIUS ROSENBERG

May 12, 1918–June 19, 1953

By William R. Conklin

OSSINING. N.Y.—Stoic and tight-lipped to the end, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg paid the death penalty tonight in the electric chair at Sing Sing Prison for their war-time atomic espionage for Soviet Russia.

The pair, first husband and wife to pay the supreme penalty here, and the first in the United States to die for espionage, went to their deaths with a composure that astonished the witnesses.

Both executions of the death sentence had been advanced from the usual Sing Sing hour of 11 P.M. so that they would not conflict with the Jewish Sabbath. The last rays of a red sun over the Hudson River were casting a faint light when the double execution was completed.

By A. H. Raskin

The execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on Friday night brought to an end a case that has stirred more worldwide interest than any American judicial proceeding since the Sacco-Vanzetti trial a quarter of a century ago. The Rosenbergs were sentenced to death for a new kind of crime in a new age—the age of atomic destruction. What follows is a narrative of the Rosenbergs’ story as it was developed at their trial.

The depression brought Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to communism, and communism brought them to one another. Born on Manhattan’s poverty-ridden East Side, they embraced the Communist movement in their teens while millions of Americans were out of work and Franklin D. Roosevelt was struggling to put a splintered economy back into one piece.

They met at Seward Park High School. She got a job as a stenographer after graduation; he went on to City College and won his degree in electrical engineering in February, 1939. A few months later Julius and Ethel were married.

He became a junior engineer in the Army Signal Corps on Sept. 3, 1940. After Pearl Harbor, with the United States and Russia established as war-time allies, Julius began to brood over the reluctance of our Government to entrust all its military secrets to the Soviet Union. He decided that the Russians were entitled to know everything we knew.

His first big opportunity to help the Russians came in August, 1944, when the Army assigned Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass, a machinist, to work on the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, N.M.

In November, 1941, David’s wife, Ruth, visited him and told him that she had had dinner with the Rosenbergs in their Knickerbocker Village apartment. They disclosed that they had joined the Communist underground—they were shunning open association with the party’s activities, staying away from its meetings and not buying The Daily Worker.

Julius urged her to rush out to New Mexico and bring back facts about the bomb for transmission to the Russians. Resistant at first, she changed her mind. She told David of Julius’s argument that Russia was fighting side by side with the United States and was not getting data she ought to have. David agreed to supply the information Julius wanted about the physical layout at Los Alamos, the number of people working there and the names of the key scientists supervising the project.

She memorized David’s answers and carried them back to New York. In January David came home himself on a furlough. Working from memory, David made sketches of a high-explosive lens, for which he had made molds in his New Mexico machine shop. (The lens is a curve-shaped high explosive used to set off the chain reaction that detonates the bomb.)

Greenglass was able to supplement his sketches with a mass of technical material about the bomb. Julius was jubilant when David delivered his information. He said the sketches were “very good.” Ethel typed up the data. It took 12 pages to get it all down.

What did Julius do with the material he got from David? According to the Greenglasses, he had microfilming equipment concealed in a hollowed-out section of a console table given to him by the Russians. Whenever he had a message or microfilm to turn over, he would leave it in the alcove of a movie theater. When a meeting seemed in order, he would leave a note in the alcove, then rendezvous with his contacts in little-frequented spots on Long Island. Greenglass testified that on his visit to New York Rosenberg had arranged to have him meet a Russian, whose name David never learned, on First Avenue.

When David went back to his post, he took Ruth with him. He also took plans for supplying more information to Julius’s Russian friends. Julius gave Greenglass an irregularly cut section of a Jell-o package and told him to have his information ready for transmission to a courier, who would present the matching part of the package as identification.

The courier was Harry Gold, a Swiss-born biochemist and a member of the Communist spy ring since 1935. He had no direct dealings with Rosenberg and he never made his identity known to Greenglass. Gold’s contact was Anatoli A. Yakovlev, Soviet Vice Consul in New York. He gave Gold a double-barreled mission to New Mexico in June, 1945.

One task was to go to Santa Fe and get data from Dr. Klaus Fuchs, a high-ranking British atomic scientist, from whom Gold had obtained vital material before. The other part was to visit Greenglass in Albuquerque.

In Albuquerque, Gold went through the prescribed ritual of recognition signal and panel presentation. Greenglass walked across the parlor and fished the matching section out of his wife’s pocketbook. The pudgy-faced courier introduced himself as “Dave from Pittsburgh.”

Before departing with a fresh set of drawings and explanatory material from Greenglass, Gold gave the G.I. an envelope containing $500. The money came from Yakovlev. Two days later, Gold met the Russian in Brooklyn and handed him the information from Fuchs and Greenglass. Two weeks later Yakovlev told Gold that the material had been sent to the Soviet Union and that the data from Greenglass had proved “extremely excellent and very valuable.”

Rosenberg did not confine himself to atomic information. He confided to Greenglass that he had stolen the proximity fuse while he was working at the Emerson Radio Company on a Signal Corps project and gave it to the Russians.

In 1948, he made contact with a former City College student, Morton Sobell, an electronics and radar expert, who worked on the classified Government contracts, and received a 35mm film can filled with secret information. Tried with the Rosenbergs, Sobell drew a 30-year jail sentence.

Rosenberg knew that the end was in sight for him when the British announced the arrest of Klaus Fuchs in February, 1950. He warned Greenglass that Gold would be taken into custody soon and he recommended that David leave the country.

When the F.B.I. jailed Gold on May 23, Rosenberg went into high gear. He gave Greenglass $1,000 and promised that the Russians would supply as much more as was needed to get David, his wife and their two small children out of the United States.

The thought of fleeing with a two-week-old infant did not appeal to David and Ruth, but they pretended to fall in with the plan. Rosenberg gave them another $4,000, wrapped in brown paper. In the meantime, the Rosenbergs prepared to get out of the country. But they were still here when Julius was arrested on July 17, 1950. Ethel was arrested less than a month later.

The only one who did leave after Fuchs and Gold had been apprehended was Sobell. He flew to Mexico City on June 21 with his family. He was deported from Mexico and arrested at the Texas border.

The Rosenbergs denied throughout their trial that they had anything to do with espionage. They denied everything the Greenglasses and Gold swore to. They refused to answer questions about membership in the Communist party or the Young Communist League on grounds of possible self-incrimination, but swore that they were loyal to the United States.

The defense argued that David Greenglass had perjured himself to save his wife at the expense of his sister. Efforts also were made to get across the idea that Greenglass was personally unstable and unreliable, that he had been coached by the F.B.I., and that he had a grudge against Julius Rosenberg because of a business row when they were partners in a machine shop after the war. Ruth Greenglass was not indicted.

The echoes of the case will be heard as long as the “cold war” goes on. The evidence that brought the jury’s verdict and the judge’s sentence will be lost in endless clouds of emotion, much of it politically generated.

ADOLF EICHMANN

March 19, 1906–June 1, 1962

By Lawrence Fellows

RAMLE, Israel—Adolf Eichmann was hanged just before last midnight for the part he played in rounding up millions of Jews and transporting them to their deaths in Nazi camps during World War II.

President Itzhak Ben-Zvi rejected Eichmann’s appeal for mercy shortly before the execution.

Eichmann’s body was cremated early today, as had been requested in his will. The ashes were scattered in the Mediterranean outside Israeli waters.

Cold and unyielding to the end, Eichmann rejected an appeal by a Protestant minister that he repent. His last words, spoken in German to a small group of witnesses in the execution chamber, were:

“After a short while, gentlemen, we shall all meet again. So is the fate of all men. I have lived believing in God and I die believing in God.

“Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are the countries with which I have been most closely associated and I shall not forget them.

“I greet my wife, my family and friends. I had to obey the rules of war and my flag. I am ready.”

The hanging was carried out in the gloomy, fogbound Ramle Prison only a few hours after Eichmann’s final plea had been rejected by President Ben-Zvi.

During the day, the President had received hundreds of appeals for clemency. A delegation of Hebrew University professors, headed by the philosopher Martin Buber, urged him to prevent the execution.

But a brief announcement by the President’s office last night said: “The President of the State of Israel has decided not to exercise his prerogative to pardon offenders or reduce sentences in the case of Adolf Eichmann.”

On receiving this word, the Rev. William Hull, the Canadian missionary assigned by the Government to attend Eichmann, returned to the prison, where he had talked with the prisoner earlier.

The minister’s wife, who served as his interpreter, said Eichmann had seemed hard and bitter after the Supreme Court rejected his appeal Tuesday.

Eichmann sat down at 7 P.M. to his last meal—regular prison fare of peas, bread, olives and tea. At 8 o’clock, the Commissioner of Prisons, Avraham Nir, notified him that the President had rejected his appeal.

Eichmann did not appear surprised, the commissioner said. At the prisoner’s request, a bottle of dry red Israeli wine was brought. He drank about half of it. Two letters from a brother were brought to him and he read them.

Half an hour before midnight, Mr. Hull, head of the nondenominational Zion Christian Mission in Jerusalem, was taken to Eichmann. Again, Mrs. Hull interpreted.

Later, the minister said Eichmann “was not prepared to discuss the Bible—he did not have time to waste.”

Mrs. Hull said Eichmann looked sad, but said he was ready to die.

Mr. Hull revealed that Eichmann had asked him: “Tell my wife to take it calmly. I have peace in the heart.”

The minister led the 50-yard walk from the cell to the execution chamber. Eichmann, his hands bound behind him, walked erect and apparently calm. He coughed once.

The gallows—the first to be used in the history of Israel—had been set up in a small room that formerly served as living quarters for guards on the third floor of the prison.

Eichmann, who wore reddish brown trousers and a shirt open at the neck, was led to a black-painted trapdoor that had been cut in the floor.

Guards tied his ankles and knees. Eichmann asked them to loosen the bonds around his knees so that he could stand erect. He refused a black hood that was offered him.

Then, his eyes nearly shut, he stared slightly to the side and downward at the trap as he spoke his last words.

When he had finished, Commissioner Nir called, “Muchan!”—Hebrew for “Ready!” A noose was slipped over Eichmann’s head. Again, the commissioner called “Muchan!”

There was a rustle behind a blanket partition in a corner of the room, where three men stood at controls so rigged that none could tell which was the one controlling the gallows.

The trap opened, and Eichmann plummeted to his death.

The minister cried, “Christ, Jesus Christ.”

In unanimous judgment, five justices of the Supreme Court accepted Tuesday the reasons and conclusions of the specially composed district court that tried Eichmann a year ago and sentenced him to death last December.

“The man,” the Supreme Court wrote, “who was entrusted by no lesser eminence than Reinhard Heydrich, Gestapo General, himself, with the task of dealing with the final solution of 11 million Jews is no mere screw, small or large, of a machine propelled by others. He is himself one of those who propel the machine.”

Eichmann objected to these findings in his appeal. “The judges of Israel,” he wrote, “made a basic mistake because they did not distinguish between the responsible leaders, those who gave the orders, and the men of the line who only carried the orders out.”

The argument was knocked down repeatedly in court. The supreme court held:

“The appellant has never shown either repentance or weakness or any sapping of strength or any weakening of will in the performance of the task which he undertook.

“He was the right man in the right place and he carried out his unspeakably horrible crimes with genuine joy and enthusiasm to his own gratification and the satisfaction of all his superiors.”

OSAMA BIN LADEN

March 10, 1957–May 2, 2011

WASHINGTON—Osama bin Laden, the mastermind of the most devastating attack on American soil in modern times and the most hunted man in the world, was killed in a firefight with United States forces in Pakistan on Sunday, President Obama announced.

In a dramatic late-night appearance in the East Room of the White House, Mr. Obama declared that “justice has been done” as he disclosed that American military and C.I.A. operatives had finally cornered bin Laden, the Al Qaeda leader who had eluded them for nearly a decade. American officials said bin Laden resisted and was shot in the head. He was buried at sea.

The news touched off an extraordinary outpouring of emotion as crowds gathered outside the White House, in Times Square and at the Ground Zero site, waving American flags, cheering, shouting, laughing and chanting, “USA, USA!”

Bin Laden’s demise is a defining moment in the American-led war on terrorism, a symbolic stroke affirming the relentlessness of the pursuit of those who attacked New York and Washington on Sept. 11, 2001.

When the end came for bin Laden, he was found not in the remote tribal areas along the Pakistani-Afghan border, where he had long been presumed to be sheltered, but in a massive compound about an hour’s drive north from the Pakistani capital of Islamabad. He was hiding in the medium-size city of Abbottabad, home to a large Pakistani military base and an Army academy.

The house at the end of a narrow dirt road was roughly eight times larger than other homes in the area, but had no telephone or television connections. When American operatives converged on the house on Sunday, bin Laden “resisted the assault force” and was killed in the middle of a gun battle, a senior administration official said, but details were still sketchy early Monday morning.

By Kate Zernike and Michael T. Kaufman

Osama bin Laden was a son of the Saudi elite whose radical, violent campaign to recreate a seventh-century Muslim empire redefined the threat of terrorism for the 21st century.

With the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001, Bin Laden was elevated to the realm of evil in the American imagination once reserved for dictators like Hitler and Stalin. He was a new national enemy, his face on wanted posters. He gloated on videotapes, taunting the United States and Western civilization. He was generally believed to be 54.

Terrorism before bin Laden was often state-sponsored, but he was a terrorist who had sponsored a state. From 1996 to 2001 he bought the protection of the Taliban, then the rulers of Afghanistan, and used the time and freedom to make Al Qaeda—which means “the base” in Arabic—into a multinational enterprise for the export of terrorism. Groups calling themselves Al Qaeda, or acting in the name of its cause, attacked American troops in Iraq, bombed tourist spots in Bali and blew up passenger trains in Spain.

He waged holy war with modern methods. He sent fatwas—religious decrees—by fax and declared war on Americans in an e-mail beamed by satellite around the world. He styled himself a Muslim ascetic, a billionaire’s son who gave up a life of privilege for the cause. But he was media savvy and acutely image-conscious.

His reedy voice seemed to belie the warrior image he cultivated, a man whose constant companion was a Kalashnikov rifle, which he boasted he had taken from a Russian soldier he had killed in the war in Afghanistan. While he built his reputation on his combat experience against Soviet troops, even some of his supporters questioned whether he had actually fought.

Bin Laden claimed to follow the purest form of Islam, but many scholars insisted that he was glossing over the faith’s edicts against killing innocents and civilians. Yet it was the United States, bin Laden insisted, that was guilty of a double standard. “It wants to occupy our countries, steal our resources, impose agents on us to rule us and then wants us to agree to all this,” he told CNN in 1997.

He sought to topple infidel governments through jihad, or holy war.

He modeled himself after the Prophet Muhammad, who in the seventh century led the Muslim people to rout the infidels, or nonbelievers, from North Africa and the Middle East.

In his vision, bin Laden would be the “emir,” or prince, in a restoration of the khalifa, a political empire extending from Afghanistan across the globe. Al Qaeda became the infrastructure for his dream.

Osama bin Muhammad bin Awad bin Laden was born in 1957, the seventh son and 17th child, among 50 or more, of his father, people close to the family say.

His father, Muhammad bin Awad bin Laden, had in 1931 immigrated from Yemen to what would soon become Saudi Arabia. There he began as a janitor and rose to become owner of the largest construction company in Saudi Arabia. Bin Laden’s mother, the last of his father’s four wives, was from Syria.

Bin Laden was educated in Wahhabism, a puritanical, ardently anti-Western strain of Islam. By most accounts he was devout and quiet, marrying a relative, the first of his four wives, at age 17.

It was at King Abdulaziz University in Jidda that he shaped his militancy, and in 1979, when Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan, he arrived at the Pakistan-Afghanistan border within two weeks of the occupation. Later he brought into Afghanistan construction machinery and recruits. In 1984, he helped set up guesthouses in Peshawar, the first stop for holy warriors on their way to Afghanistan, and establish the Office of Services, which branched out across the world to recruit young jihadists, as many as 20,000.

The crucible of Afghanistan prompted the founding of Al Qaeda and brought bin Laden into contact with leaders of other Islamists, including Ayman al-Zawahiri, whose group, Egyptian Jihad, would merge with Al Qaeda.

Through the looking glass of Sept. 11, it seemed ironic that the Americans and Osama bin Laden had fought on the same side against the Soviets in Afghanistan—as if the Americans had somehow created the bin Laden monster by providing arms and cash to the Arabs.

Bin Laden himself said the resistance received training and money from the Americans. In truth, the Americans did not deal directly with bin Laden; they worked through the middlemen of the Pakistani intelligence service.

The triumph in Afghanistan infused the movement with confidence.

Bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia, welcomed as a hero. But Saudi royals grew wary of him as he became more outspoken against the government. He opposed the Saudis’ decision to allow the Americans to defend the kingdom during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. To him, it was the height of American arrogance.

Bin Laden fled to Sudan and set up legitimate businesses that would help finance Al Qaeda. It was during this time that it is believed he honed his resolve against the United States.

On Dec. 29, 1992, a bomb exploded in a hotel in Aden, Yemen, where American troops had been staying while on their way to Somalia. The troops had already left, and the bomb killed two Austrian tourists. American intelligence officials came to believe that it was bin Laden’s first attack.

On Feb. 26, 1993, a bomb exploded at the World Trade Center, killing six people. Bin Laden later praised Ramzi Yousef, who was convicted of the bombing. That year, in Somalia, 18 American service members were killed—some of their bodies dragged through the streets—while on a peacekeeping mission; bin Laden was almost giddy about the deaths and their impact on Islamist fighters.

“The youth were surprised at the low morale of the American soldiers and realized more than before that the American soldier was a paper tiger and after a few blows ran in defeat,” he told an interviewer.

By 1994, bin Laden had established training camps in Sudan. He called for guerrilla attacks to drive Americans from Saudi Arabia. In November 1995, a truck bomb exploded at a Saudi National Guard training center operated by the United States in Riyadh, killing seven people.

The next May, when the men accused of the bombing were beheaded, they were forced to confess the connection to bin Laden. The next month, June 1996, a truck bomb destroyed Khobar Towers, an American military residence in Dhahran. It killed 19 soldiers.

Bin Laden fled to Afghanistan that summer after Sudan expelled him under pressure from the Americans and Saudis, and he forged an alliance with the Taliban. In August 1996, he issued his “Declaration of War Against the Americans Who Occupy the Land of the Two Holy Mosques.”

The imbalance of power between American and Muslim forces demanded a new kind of fighting, he wrote, “in other words, to initiate a guerrilla war, where sons of the nation, not the military forces, take part in it.”

In February 1998, he called for attacks on Americans anywhere in the world, declaring it an “individual duty” for all Muslims.

On Aug. 7, 1998, the eighth anniversary of the United States order sending troops into the Gulf region, two bombs exploded simultaneously at the American Embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The Nairobi bomb killed 213 people and wounded 4,500; the bomb in Dar es Salaam killed 11 and wounded 85.

The United States retaliated with strikes against what were thought to be terrorist training camps in Afghanistan and a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan, which officials contended—erroneously, it turned out—was producing chemical weapons for Al Qaeda.

Bin Laden had trapped the United States in a spiral of tension, where any defensive or retaliatory actions would affirm the evils that he said had provoked the attacks in the first place.

After Sept. 11, bin Laden eluded the allied forces in pursuit of him, moving, it was said, under cover of night, at first between mountain caves. Yet he was determined that if he had to die, he would die a martyr’s death.

His greatest hope, he told supporters, was that if he died at the hands of the Americans, the Muslim world would rise up and defeat the nation that had killed him.