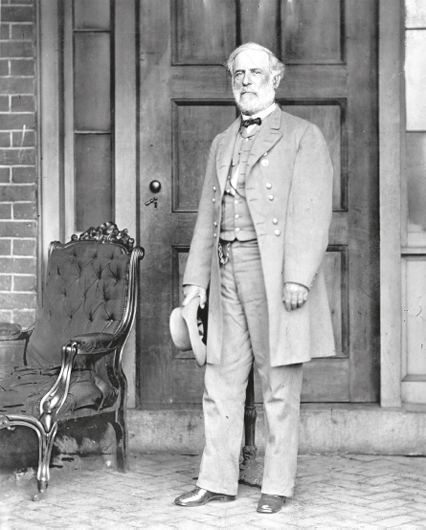

ROBERT E. LEE

January 19, 1807–October 12, 1870

Intelligence was received last evening of the death at Lexington, Va., of Gen. Robert E. Lee, the most famous of the officers whose celebrity was gained in the service of the Southern Confederacy during the late terrible rebellion.

A report was received some days ago that he had been smitten with paralysis, but this was denied, and hopes of his speedy recovery were entertained by his friends.

Within the last few days his symptoms had taken an unfavorable turn, and he expired at 9 o’clock yesterday morning of congestion of the brain, at the age of 63 years, 8 months and 23 days.

Robert Edmund Lee was the son of Gen. Henry Lee, the friend of Washington, and a representative of one of the wealthiest and most respected families of Virginia.

Born in January, 1807, he grew up amid all the advantages which wealth and family position could give in a republican land, and received the best education afforded by the institutions of his native State.

Having inherited a taste for military studies, he entered the National Academy at West Point in 1825, and graduated in 1829, the second in scholarship in his class. He was at once commissioned Second Lieutenant of engineers, and in 1835 acted as Assistant Astronomer in drawing the boundary line between the States of Michigan and Ohio.

In the following year he was promoted to the grade of First Lieutenant, and in 1836 received a Captain’s commission. On the breaking out of the war with Mexico, he was made Chief-Engineer of the army under the command of Gen. Wool.

After the battle of Cerro Gordo, in April, 1847, in which he distinguished himself by his gallant conduct, he was promoted to the rank of Major. He displayed equal bravery at Contreras, Cherubusco and Chapultepec, and in the battle at the last-mentioned place received a severe wound. His admirable conduct throughout this struggle was rewarded with the commission of a Lieutenant-Colonel and the title of Colonel.

In 1852 he was appointed to the position of Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point, which he retained until 1855. On retiring from this position he was made Lieutenant-Colonel of the Second Calvary, and on the 16th of March, 1861, received the commission of Colonel of the First Calvary.

Thus far the career of Col. Lee had been one of honor and the highest promise. In every service entrusted to him he had proved efficient, prompt and faithful, and his merits had always been readily acknowledged and rewarded by promotion. He was regarded by his superior officers as one of the most brilliant and promising men in the army of the United States.

His personal integrity was well known, and his loyalty and patriotism were not doubted. But he seems to have been imbued with that pernicious doctrine that his first and highest allegiance was due to the State of his birth.

When Virginia joined the ill-fated movement of secession from the Union, he immediately threw up his commission in the Federal Army and offered his sword to the newly formed Confederacy, declaring that his sense of duty would never permit him to “raise his hand against his relatives, his children, and his home.”

In his farewell letter to Gen. Winfield Scott, he spoke of the struggle which this step had cost him, and his wife declared that he “wept tears of blood over this terrible war.”

Probably few doubt the sincerity of his protestation, but thousands have regretted the error of judgment, the false conception of the allegiance due to his Government and his country, which led one so gifted to cast his lot with traitors and devote his splendid talents to the execution of a wicked plot to tear asunder the Republic.

He resigned his commission on the 25th of April, 1861, and immediately betook himself to Richmond, where he was received with open arms and put in command of all the forces of Virginia by Gov. Letcher. On the 10th of May he received the commission of a Major-General in the army of the Confederate States, retaining the command in Virginia, and was soon promoted to the rank of General in the regular army.

He first took the field in the mountainous region of Western Virginia, where he was defeated at Greenbrier by Gen. J. J. Reynolds on the 3rd of October, 1861. He was subsequently sent to take command of the Department of the South Atlantic Coast, but was later recalled to Virginia, and placed at the head of the forces defending the capital.

He engaged with the Army of the Potomac under his old companion-in-arms, Gen. McClellan, and drove it back to the Rappahannock. He afterward, in August, 1862, attacked the Army of Virginia, under Gen. Pope, and after driving it back to Washington, crossed the Potomac into Maryland, where he issued a proclamation calling upon the inhabitants to enlist under his triumphant banners.

Meantime, McClellan gathered a new army from the broken remnants of his former forces, met Lee at Hagerstown, and, after a battle of two days, compelled him to retreat. Reinforced by “Stonewall” Jackson, on the 16th of September, Lee turned to renew the battle, but after two days of terrible fighting at Sharpsburg and Antietam, was driven from the soil of Maryland.

Retiring beyond the Rappahannock, he took up his position at Fredericksburg, where he was attacked, on the 13th of December, by Gen. Burnside, whom he drove back with terrible slaughter.

Gen. Lee met with the same success in May, 1863, when attacked by Hooker, at Chancellorsville. Encouraged by these victories, in the ensuing Summer he determined to make a bold invasion into the territory of the North. He met Gen. Meade at Gettysburg, Penn., on the 1st of July, 1863, and after one of the most terrible battles of modern times, was driven from Northern soil.

Soon after this, a new character appeared on the battlefields of Virginia, and Gen. Lee gathered his forces for the defense of the Confederate capital against the onslaughts of Gen. Grant. In the Spring and Summer of 1864 that indomitable soldier gradually enclosed the City of Richmond as with a girdle of iron, which he drew closer and closer, repulsing the rebel forces whenever they ventured to make an attack.

In this difficult position, holding the citadel of the Confederacy, and charged with its hopes and destinies, Lee was made Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the South. He held out until the Spring of 1865, vainly endeavoring to gather the broken forces of the Confederacy, and break asunder the terrible line which was closing around them.

After a desperate and final effort at Burkesville, on the 9th of April, 1865, he was compelled to acknowledge his defeat, and surrendered his sword to Gen. Grant on the generous terms dictated by that great soldier.

Lee retired under his parole to Weldon, and soon after made a formal submission to the Federal Government. Subsequently, by an official clemency, which is probably without a parallel in the history of the world, he was formally pardoned for his part in the mad effort of the Southern States to break up the Union and destroy the Government.

Not long after his surrender he was invited to become the President of Washington University, at Lexington, Va., and was installed in that position on the 2nd of October, 1865. Since that time he has devoted himself to the interests of that institution, and by his unobtrusive modesty and purity of life, has won the respect even of those who most bitterly deplore his course in the rebellion.

GEORGE CUSTER

December 5, 1839–June 25, 1876

SALT LAKE CITY—The special correspondent of the Helena (Montana) Herald writes from Stillwater, Montana, under date of July 2, as follows:

Muggins Taylor, a scout for Gen. Gibbon, arrived here last night direct from Little Horn River, and reports that Gen. [George Armstrong] Custer found the Indian camp of 2,000 lodges on the Little Horn, and immediately attacked it. He charged the thickest portion of the camp with five companies. Nothing is known of the operations of this detachment, except their course as traced by the dead. Major Reno commanded the other seven companies, and attacked the lower portion of the camp. The Indians poured a murderous fire from all directions. Gen. Custer, his two brothers, his nephew, and brother-in-law were all killed, and not one of his detachment escaped. Two hundred and seven men were buried in one place. The number of killed is estimated at 300, and the wounded at 31.

The Seventh fought like tigers, and were overcome by mere brute force. The Indian loss cannot be estimated. The Indians got all the arms of the killed soldiers. There were 17 commissioned officers killed. The whole Custer family died at the head of their column. The Indians actually pulled men off their horses, in some instances.

This report is given as Taylor told it, as he was over the field after the battle. The above is confirmed by other letters, which say Custer has met with a fearful disaster.

Major Gen. George Armstrong Custer, who was killed with his whole command while attacking an encampment of Sioux Indians, under command of Sitting Bull, was one of the bravest and most widely known officers in the United States Army. He has for the past 15 years been known to the country and to his comrades as a man who feared no danger, as a soldier in the truest sense of the word. He was daring to a fault, generous beyond most men. His memory will long be kept green in many friendly hearts.

Born at New-Rumley, Harrison County, Ohio, on the 5th of December, 1839, he obtained a good common education, and after graduating engaged for a time in teaching school. In June, 1857, he obtained an appointment to the United States Military Academy.

He graduated on the 24th of June, 1861, with what was considered the fair standing of No. 34 in one of the brightest classes that ever left the academy. Immediately upon leaving West Point he was appointed Second Lieutenant in Company G of the Second United States Cavalry, a regiment which had formerly been commanded by Robert E. Lee.

He reported to Lieut. Gen. Scott on the 20th of July, the day preceding the battle of Bull Run, and the Commander in Chief gave him the choice of accepting a position on his staff or of joining his regiment, then under command of Gen. McDowell, in the field. Lieut. Custer chose the latter course, and after riding all night through a country filled with people who were, to say the least, not friendly, he reached McDowell’s head-quarters at daybreak on the 21st.

Preparations for the battle had already begun, and after delivering his dispatches from Gen. Scott and hastily partaking of a mouthful of coffee and a piece of hard bread, he joined his company. It is not necessary now to recount the disasters of the fight that followed. Suffice it to say that Lieut. Custer’s company was among the last to leave the field.

The young officer continued to serve with his company, and was engaged in the drilling of volunteer recruits in and about the defenses of Washington, when upon the appointment of Phil Kearny to the position of Brigadier General, that officer gave him a position on his staff.

With his company Lieut. Custer marched forward with that part of the Army of the Potomac which moved upon Manassas after its evacuation by the rebels. Our cavalry was in advance and encountered the rebel horsemen for the first time near Catlett’s Station.

The commanding officer made a call for volunteers to charge the enemy’s advance post. Lieut. Custer was among the first to step to the front, and in command of his company he shortly afterward made his first charge. He drove the rebels across Muddy Creek, wounded a number of them, and had one of his own men injured.

After this Custer went with the Army of the Potomac to the Peninsula and remained with his company until the Army settled down before Yorktown, when he was detailed as an Assistant Engineer. Acting in this capacity he planned and erected the earthworks nearest the enemy’s lines. He also accompanied the advance under Gen. Hancock in pursuit of the enemy from Yorktown. Shortly afterward, he captured the first battle-flag ever secured by the Army of the Potomac.

From this time on he was nearly always the first in every work of daring. When the Army reached the Chickahominy he was the first man to cross the river; he did so in the face of the fire of the enemy’s pickets, and at times was obliged to wade up to his armpits. For this brave act Gen. McClellan promoted him to a Captaincy and made him one of his personal aides. In this capacity he served during most of the Peninsula campaign, and participated in all its battles.

He performed the duty of marking out the position which was occupied by the Union Army at the battle of Gaines’ Mills. He also participated in the campaign which ended in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam.

He was next engaged in the battle of Chancellorsville, and immediately after that fight he was made a personal aide by Gen. Pleasonton, who was then commanding a division of cavalry. Serving in this capacity, he marked himself as one of the most dashing, some said the most reckless, officers in the service.

When Pleasonton was made a Major General, he requested the appointment of four Brigadiers to command under him. Young Custer was made a Brigadier General and assigned to the command of the First, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Michigan Cavalry.

He did noble service at the battle of Gettysburg. He held the right of line, and was obliged to face Hampton’s division of cavalry, and after a hotly contested fight, utterly routed the rebels. Custer had two horses shot under him.

Hardly had the battle concluded when he was sent to attack the enemy, which was trying to force its way to the Potomac. He destroyed more than 400 wagons.

At Hagerstown, Md., Custer again had his horse shot under him. At Falling Waters, shortly after, he attacked with his small brigade the entire rebel rear guard. The Confederate commander Gen. Pettigrew was killed and his command routed, with a loss of 1,300 prisoners.

Custer participated in the battle of the Wilderness in 1864, and on the 9th of May of the same year, under Gen. Sheridan, he set out on the famous raid toward Richmond. His brigade led the column, captured Beaver Dam, burned the station and a train of cars loaded with supplies, and released 400 Union prisoners. After the battle of Fisher’s Hill, he was placed in command of a division, and remained in that position until after Lee’s surrender.

When the rebels fell back to Appomattox, Custer had the advance of Sheridan’s command, and his share in the action is well described in the entertaining volume entitled “With Sheridan in His Last Campaign.”

“When the sun was an hour high in the west, energetic Custer in advance spied the depot and four heavy trains of freight ears,” the book says. “He quickly ordered his leading regiments to circle out to the left through the woods, and as they gained the railroad beyond the station he led the rest of his division pell-mell down the road and enveloped the train as quick as winking.

“At the head of the horsemen rode Custer of the golden locks, his broad sombrero turned up from his hard, bronzed face, the ends of his crimson cravat floating over his shoulder, gold galore spangling his jacket sleeves, a pistol in his boots, jangling spurs on his heels, and a ponderous claymore swinging at his side; a wild, dare-devil of a General.”

On July 28, 1866, he was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the Seventh United States Cavalry for service on the frontier.

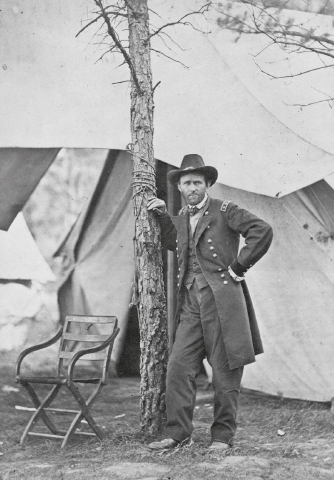

ULYSSES S. GRANT

April 27, 1822–July 23, 1885

MOUNT McGREGOR, NY—Surrounded by all of his family and with no sign of pain, Gen. [Ulysses S.] Grant passed from life at six minutes after eight o’clock this morning. The end came with so little immediate notice as to be in the nature of a surprise. All night had the family been on watch, part of the time in the parlor, where he lay, rarely venturing further away from him than the porch on which the parlor opens.

The General did not speak even in a whisper after 3 o’clock this morning. It was soon evident that he was too far gone to be aided by stimulants. Then came the waiting for death. The General lay on the bed, his face leaden, yet with some warmth left in its hue. His eyes were closed. Power to open them had been restored to him, and it was occasionally invoked when some member of the family, or the doctor, or one of the attendants spoke to him. Then he would open his eyes. He could make no other recognition, but that of the eyes was clear. His lungs and pulse were failing, but there was yet no cloud on the brain.

The rays of the morning sun fell across the cottage porch upon a family waiting only for death. The doctor said he would inform them instantly of any change. [About 7:45] a change had come. Dr. Shrady sent for the family. The bed stood in the middle of the room. Dr. Douglas drew a chair to the head near the General. Mrs. Grant came in and sat on the opposite side. She clasped gently one of the white hands in her own.

When the Colonel came in, Dr. Douglas gave up his chair to him. The Colonel began to stroke his father’s forehead, as was his habit when attending him. Only the Colonel and Mrs. Grant sat. Mrs. Sartoris stood at her mother’s shoulder, Dr. Shrady a little behind. Jesse Grant leaned against the low headboard fanning the General. Ulysses junior stood at the foot. Dr. Douglas was behind the Colonel. The wives of the three sons were grouped near the foot. Harrison was in the doorway, and the nurse, Henry, near a remote corner. Between them, at a window, stood Dr. Sands. The General’s little grandchildren, U. S. Grant, Jr., and Nellie, were sleeping the sleep of childhood in the nursery room above stairs.

All eyes were intent on the General. His breathing had become soft, though quick. A shade of pallor crept slowly but perceptibly over this features. His bared throat quivered with the quickened breath. The outer air, gently moving, swayed the curtain at an east window. In the crevice crept a white ray from the sun. It reached across the room like a rod and lighted a picture of Lincoln over the deathbed. The sun did not touch the companion picture, which was of the General. A group of watchers in a shaded room, with only this quivering shaft of pure light, the gaze of all turned on the pillowed occupant of the bed, all knowing that the end had come, and thankful, knowing it, that no sign of pain attended it—this was the simple setting of the scene.

The General made no motion. Only the fluttering throat, white as his sick robe, showed that life remained. The face was one of peace. There was no trace of present suffering. The moments passed in silence. The light on the portrait of Lincoln was slowly sinking. Presently the General opened his eyes and glanced about him, looking into the faces of all. The glance lingered as it met the tender gaze of his companion. A startled, wavering motion at the throat, a few quiet gasps, a sigh, and the appearance of dropping into gentle sleep followed. The eyes of affection were still upon him. He lay without a motion. At that instant the window curtain swayed back in place, shutting out the sunbeam.

“At last,” said Dr. Shrady, in a whisper.

“It is all over,” sighed Dr. Douglas.

Mrs. Grant could not believe it until the Colonel, realizing the truth, kneeled at the bedside clasping his father’s hand. Then she buried her face in her handkerchief. There was not a sound in the room, no sobbing, no unrestrained show of grief. The example set by him who had gone so quietly kept grief in check at that moment. The doctors withdrew. Dr. Newman, who had entered in response to a summons just at the instant of the passing away, looked into the calm face, now beyond suffering, and bowed his head. There was a brief silence. Then Dr. Newman led Mrs. Grant to a lounge, and the others of the family sought their rooms.

The General had not been dead two minutes when the wires were sending it over the country. It was known in New York before some of the guests heard of it at the hotel, where it spread very quickly. Undertaker Holmes was on his way from Saratoga almost as soon as the family had withdrawn to their rooms. A special train which had waited for him all night was at once dispatched for him. Sculptor Gohardt was informed that he might take the death mask. The General’s body still lay on the bed clad in the white flannel gown and the light apparel that he had last worn. The face seemed to have filled out somewhat, looking more as in familiar portraits of him.

It was yet early in the morning when dispatches of condolence and offers of help began to come in on the family. One was from the Managers of the Soldiers’ Home at Washington, offering for the place of interment a site in the grounds at the Home, carefully selected and on an eminence overlooking the city.

Col. Grant said that recently the General had written a note embodying his wishes in regard to the subject of removal from here. He was then anticipating death during this month. It would be too bad, he wrote, to send the family back to the city in the hot weather on account of his death. He proposed, therefore, that his body be embalmed and kept on this hill until the weather should become cool enough to let them go back to the city in comfort, and allow an official burial if one should be desired. The General’s supposition in writing this note was that he would be buried in New York. Washington was not one of the places named.

He did not know that the family had been in correspondence with Gen. Sheridan, in April, about a burial place at Washington, or that Gen. Sheridan had selected a site on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home. It was urged this morning [that] the General might have preferred Washington above any other place, but that he had omitted to mention it because of modesty. The disposition of the family, however, was to follow his wishes.

[The note was written on June 24. Gen. Grant] stepped into the office room early in the evening and handed to Col. Grant a slip of paper on which was written substantially this:

“There are three places from which I wish a choice of burial place to be made:

“West Point.—I would prefer this above others but for the fact that my wife could not be placed beside me there.

“Galena, or some place in Illinois.—Because from that State I received my first General’s commission.

“New York.—Because the people of that city befriended me in my need.”

When he had delivered this slip to the Colonel he walked back into the sick room. In a few minutes he reappeared, walking round in front of the Colonel.

“I don’t like this, father,” the son said, holding out the slip.

“What is there about it you don’t like?” asked the General, in his husky whisper.

“I don’t like any of it. There is no need of talking of such things.”

The General took the slip, folded it, tore it lengthwise, across, and again until the pieces were so small that hardly a word could have been made out from any of them, and throwing them in the waste basket went back to his room without speaking.

This was the first time the General indicated any wish in regard to his burial. The family, however, had done something toward it in April, when he was supposed to be dying. At that time, while some of them had not abandoned hope, the matter was discussed as a possibility. It was agreed that if he should die, there would be little time, in the confusion sure to prevail, to decide on that matter. Correspondence was accordingly opened with Gen. Sheridan, who thought, as did many others, that at the Soldiers’ Home in Washington would be the best place for burial, because the General saved that city; and arrangements were made to take his body there.

In view of [Gen. Grant’s] expressed wish, however, it is more than likely that he will be buried in New York. The spot selected, whether it be Central Park, as was talked of in the Spring, or elsewhere, will certainly be accepted by the family only on condition that Mrs. Grant may be laid beside him.

[The General’s final weeks and days proved highly emotional for Mrs. Grant, yet she remained hopeful.]

One evening, as the General sat in the parlor with the family, the Colonel mentioned having that day received a letter from Webster & Co., the publishers of [his] memoirs, saying that subscriptions to the book already guaranteed $300,000 to the General. Taking up his pad, the General wrote:

“That will be all for you, Julia,” and handed the slip over to Mrs. Grant.

She began to cry, and could not be calmed for some time. That evening she regained courage in prayer, and the next morning she talked as hopefully as ever of the General’s recovery.

“I have seen the General in trouble before,” she often said. “Those about me were despondent over him during the war. The newspapers and my friends did not believe he would take Vicksburg. They were skeptical about what he could do in Virginia. But no one knew him as I did. I was always confident that he would succeed. I am equally sure he will come out of this trouble, for the old faith sustains me.”

Accompanying this news article was a biographical portrait of more than 40,000 words.

GEORGE PATTON

November 11, 1885–December 21, 1945

FRANKFORT ON THE MAIN, Germany—Gen. George S. Patton Jr., one of the most vivid figures among Allied combat leaders in World War II, succumbed at 5:50 P.M. (11:50 A.M., Eastern Standard Time) to a lung congestion brought on by paralysis of his chest, the result of his auto accident two weeks ago.

The end came for the former United States Third Army commander as he was sleeping in an Army hospital in Heidelberg. He was 60 years old. [Patton was buried in an American military cemetery in Luxembourg City alongside some of the fallen from the Third Army.]

—Kathleen McLaughlin

Audacious, unorthodox and inspiring, Gen. George Smith Patton Jr. led his troops to great victories in North Africa, Sicily and on the Western Front. Nazi generals admitted that of all American field commanders he was the one they most feared.

He went into action with two pearl-handled revolvers in holsters on his hips. He was the master of an unprintable brand of eloquence, yet at times he coined phrases that will live in the American Army’s traditions.

“We shall attack and attack until we are exhausted, and then we shall attack again,” he told his troops before the initial landings in North Africa, thereby summarizing the creed that won victory after victory.

At El Guettar in March of 1943 he won the first major American victory over Nazi arms. In July of that year he leaped from a landing barge and waded ashore to the beachhead at Gela, Sicily. In just 38 days the American Seventh Army, under his leadership, and the British Eighth Army, under Gen. Sir Bernard Montgomery, conquered all of Sicily.

But it was as the leader of his beloved Third Army on the Western Front that General Patton staked his claims to greatness. In 10 months his armor and infantry roared through six countries—France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria. It crossed the Seine, the Loire, the Moselle, the Saar, the Rhine, the Danube and a score of lesser rivers; captured more than 750,000 Nazis and killed or disabled 500,000 others.

There were times when not even Supreme Headquarters knew where his vanguards were. His advance units had to be supplied with gasoline and maps dropped by air.

His best-known nickname, “Old Blood and Guts,” was one that he detested but his men loved. “His guts and my blood,” his wounded veterans used to say. His explosive wrath and lurid vocabulary became legendary.

But General Patton had a softer side. He composed two volumes of poetry, which he stipulated were not to be published until after his death. He was an intensely religious man, who liked to sing in church and who knew the Episcopal Order of Morning Prayer by heart.

He seemed fated to be the center of controversy. Again and again, when his fame and popularity were at their height, some rash statement or ill-considered deed precipitated a storm. The most celebrated of these incidents was the slapping of a soldier whom he took to be a malingerer but who was actually suffering from battle fatigue.

This episode resulted in widespread demands for his removal from command and caused the Senate to delay his confirmation to the permanent rank of major general for almost a year. General [Dwight D.] Eisenhower sharply rebuked him, but insisted that his qualifications, loyalty and tenacity made him invaluable.

The turmoil had hardly died away when he caused another stir by a speech at the opening of a club for American soldiers in London. The original version of his remarks quoted him as saying that the British and American peoples were destined to rule the world, but after this had evoked an outburst of criticism, Army press relations officers insisted that he had actually said, “we British, American and, of course, the Russian people” were destined to rule.

He caused a furor by an interview he granted American correspondents in Germany after the end of the war. Discussing conditions in Bavaria, where the military government was under his command, he said too much fuss was being made over denazification and compared the Nazi party to the losers in an election between Democrats and Republicans.

General Eisenhower promptly called him on the carpet. General Patton promised that he would be loyal to the Potsdam agreements prescribing the complete and ruthless elimination of Nazism, but on Oct. 2, 1945, he was removed from the command of his Third Army. He assumed command of the Fifteenth Army, a paper organization devoted to a study of the tactical lessons to be learned from the war.

Although he signed himself George Smith Patton Jr., General Patton was actually the third in line of his family to bear that name. The original George Smith Patton, his grandfather, was a graduate of Virginia Military Institute and became a colonel in the Confederate Army. He was killed at the battle of Cedar Creek.

General Patton’s father went through V.M.I., studied law, and moved west. He married a daughter of Benjamin Wilson, the first Mayor of Los Angeles. The future general was born on the family ranch at San Gabriel, Calif., on Nov. 11, 1885, and from childhood was an expert horseman.

At the age of 18 he came east and entered V.M.I., but after a year there he entered West Point with the class of 1909. He was a poor student (all his life he was remarkably deficient in spelling) but an outstanding athlete. He excelled as a sprinter on the track team and was also an expert fencer, swimmer, rider and shot. He rose to cadet adjutant, the second highest post in the cadet corps.

On May 26, 1910, General Patton married Beatrice Ayer of Boston, who survives him. They had two daughters and a son.

In 1912 he represented the United States at the Olympic Games in Stockholm, competing in the modern pentathlon. He finished fifth among more than 30 contestants.

His first post was at Fort Sheridan, Ill., but in December, 1911, he was transferred to Fort Myer, Va., where he was detailed to design a new cavalry saber. In 1913 he went to France to study French saber methods, and on his return was made Master of the Sword at the Mounted Service School, Fort Riley, Kan.

He accompanied Gen. John J. Pershing as his aide on the punitive expedition into Mexico after the bandit Pancho Villa in 1916, and the next year he went to France with the general as a member of his staff. He attended the French Tank School and then saw action at the battle of Cambrai, where the British first used tanks on a large scale.

He was assigned to organize and direct the American Tank Center at Langres. For his service in that capacity he was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. He took command of the 304th Brigade of the Tank Corps and distinguished himself by his leadership of it in the St. Mihiel offensive in September, 1918. Later that autumn, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, he was severely wounded in the left leg. After the war, he served in various tank and cavalry posts in the United States.

When this country began to rearm in the summer of 1940 Patton was a colonel. He was sent to Fort Benning, Ga., as commander of a brigade of the Second Armored Division, then being formed. In April, 1941, he became division commander. Promoted to corps commander, he organized the Desert Training Center in California.

When the North African invasion was planned, General Patton was placed in command of the American forces scheduled to land in Morocco. After the American reverse at Kasserine Pass in February, he took command of the Second United States Corps, which forced the Nazis back into a corridor between the mountains and the sea, up which the British Eighth Army under General Montgomery pursued them.

On April 16 Gen. Omar Bradley succeeded him in command of the Second Corps.

There were rumors that General Patton had fallen into disfavor. Actually, General Eisenhower had withdrawn him from action to prepare the Seventh Army for the invasion of Sicily in July.

The invasion was brilliantly successful, and General Patton’s troops cut clear across the island to Palermo, then fought their way along the north coast to Messina.

General Patton, who drove himself as hard as he drove his men, visited a hospital not far from the front when he had been under prolonged strain. There he encountered two men who showed no signs of visible wounds, but who had been diagnosed as suffering from battle neurosis.

General Patton called them “yellow bellies” and other unprintable epithets, and struck one so hard that his helmet liner flew off.

General Eisenhower castigated General Patton, although he did not formally reprimand him. General Patton made personal apologies to all those present at the time of the episode, and later sent public apologies to each division of the Seventh Army.

General Patton did not appear during the campaign on the Italian mainland that followed, and some observers thought he had been relegated to a secondary role. Actually, General Eisenhower had picked him for a key role in the invasion of Western Europe, and he was then in England preparing for it.

For almost two months after D-Day, June 6, 1944, General Patton’s whereabouts remained a mystery. The fact that he was in England was well known, and the inability of the Nazi intelligence to locate him forced their High Command to retain the German 15th Army in the Pas de Calais area, far from the Normandy beachhead, lest he head a landing there.

Instead, the Third Army landed on the beachhead in great secrecy, and deployed behind the First Army. When the First Army broke the German lines between St. Lo and the sea on July 25, the Third Army poured through the breach to exploit it. General Patton’s armor and motorized infantry smashed across France, all the way to the Moselle, with planes dropping supplies before lack of gasoline finally halted the chase.

In the bitter autumn that followed, General Patton’s men made slow but steady headway. From Oct. 3 to Nov. 22, they carried on a sanguinary attack against Metz, which in 1,500 years of history had never before been taken by assault. They had to fight their way in, fort by fort and street by street, but they eventually took the city.

Early in December the Third Army began an attack on the Saar Basin, but the unexpected success of von Rundstedt’s offensive against the First Army’s lines to the north forced a swift change. General Patton was ordered to go to the rescue of the crumbling American positions on the south side of the “bulge.”

He redeployed his forces with astonishing speed. Within three days the Third Army had begun to pound at the southern flank of the Nazi wedge. Some of its divisions had traveled 150 miles in open trucks. By Dec. 28 they had fought their way to the relief of Bastogne. For another month they hammered away at the bulge, until it was no more.

In February the Third Army broke through the Siegfried Line and crossed the Moselle, cutting to pieces the Nazi forces in the Saar-Palatinate region. On March 17 it seized Coblenz. On April 18 the Third crossed the border of Czechoslovakia and nine days later it entered Austria. Its advance units were in the vicinity of Linz when the shooting stopped.

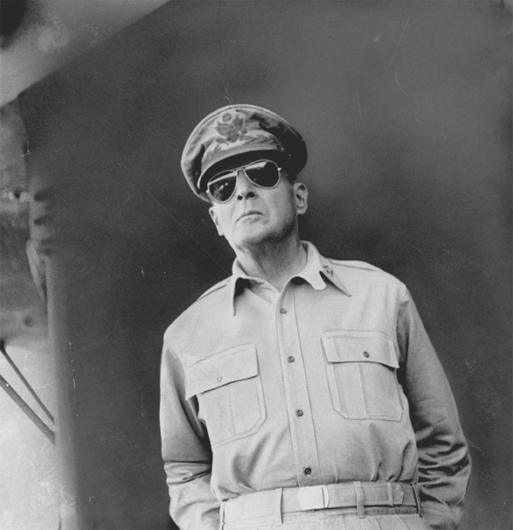

DOUGLAS MacARTHUR

January 26, 1880–April 5, 1964

WASHINGTON—General of the Army Douglas MacArthur died today after a determined fight for life. He was 84 years old.

The general, who led the Allied victory over Japan in World War II and commanded the United Nations forces in the Korean War, died at 2:39 P.M. at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he had been a patient since March 2. Death was attributed to acute kidney and liver failure.

The general’s wife, Jean, and their son, Arthur, 26, were at the hospital at the end.

—Jack Raymond

General MacArthur’s evaluation of his role in history was probably most succinctly and characteristically voiced by him in 1950 in a protracted conversation with a newspaper correspondent who had known him for many years. Asked if he could explain his success, he puffed slowly at his corncob pipe and said, “I believe it was destiny.”

Douglas MacArthur was born Jan. 26, 1880, at Fort Dodge, Little Rock, Ark. He was the third of three sons born to Capt. Arthur MacArthur and his Virginia-born wife, the former Mary Pinkney Hardy.

His eldest brother was Arthur, born in 1876, who graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1896 and had a distinguished career. The second brother, Malcolm, died at the age of five.

General MacArthur’s father was the son of Arthur MacArthur, a descendant of the MacArtair branch of the Clan Campbell. General MacArthur’s grandfather, with his widowed mother, came to this country in 1825 and settled in Chicopee Falls, Mass. He became a lawyer.

General MacArthur’s father was destined for West Point, but in August, 1862, a little more than a year after the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the 24th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry. He rose through the ranks, won the Medal of Honor in the Battle of Missionary Ridge in November, 1863, and was known as “the boy colonel.”

In 1898, the elder MacArthur was ordered to the Philippines where, following the capitulation of Spain, he fought against Emilio Aguinaldo’s revolutionaries. The elder MacArthur rose to major general commanding the Army of the Philippines, and retired as a lieutenant general.

Douglas MacArthur and his mother had remained in the United States. In 1898, Douglas took the examinations for the United States Military Academy. He passed with high marks and entered West Point in June, 1899.

His mother established a residence nearby. Her son visited her every day and graduated first in his class in 1903. As a new second lieutenant in the Corp of Engineers, he was posted to the Philippines and was involved in surveying the islands, where skirmishes with Moro dissidents were not uncommon. He once had his hat shot off.

With the outbreak of World War I, he helped to organize the 42nd (Rainbow) Division. As a brigade commander in France with the temporary rank of brigadier general, he directed actions that sometimes ran counter to grand strategy. On one occasion, with the capture of the French city of Sedan assigned to the French Army, he entered into competition with the French to be first in the town.

The prize was of particular significance to the French because it was the site of the surrender of the French to the Germans in 1870.

Orders for the operation had been drawn up by Col. George C. Marshall, an operations officer with the American Expeditionary Force. General MacArthur acted on his own interpretation of the orders. History recorded conflicting accounts of which forces first entered Sedan, but the French were listed officially as the first.

Having once told General MacArthur, “Young man, I do not like your attitude,” Gen. John J. Pershing, commanding the American Expeditionary Force, nevertheless, pinned the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal on the bold young officer.

In 1919, General MacArthur was appointed Superintendent of West Point, whose curriculum he worked to broaden.

A former varsity football and baseball player, General MacArthur encouraged intramural athletics and wrote the motto that now stands in bronze on the inner wall of West Point’s gymnasium: “Upon the fields of friendly strife are sown the seeds that, upon other fields, on other days, will bear the fruits of victory.”

General MacArthur achieved his fourth star in 1930, when he was named Chief of Staff of the Army by President Herbert Hoover.

In the summer of 1932, several thousand unemployed men, many of them veterans of World War I, gathered in Washington to demand immediate payment of war bonuses. They camped in squalor on Washington’s Anacostia Flats amid widespread sympathy for their plight, but to the vast embarrassment of the Hoover Administration.

On July 29, President Hoover ordered Chief of Staff MacArthur to clear and destroy the camp. With Maj. Dwight D. Eisenhower at his side, General MacArthur directed the operation. In some newspapers General MacArthur was pictured as a beribboned military dandy directing his troops to shoot down hungry former soldiers.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt succeeded Mr. Hoover, General MacArthur was re-appointed Chief of Staff of the Army, a post he held until 1935. But no rapport ever developed between the President and General MacArthur, who appeared unable to defer to a civilian politician.

President Roosevelt relieved General MacArthur as Chief of Staff on Oct. 3, 1935. Resuming his permanent rank of major general, General MacArthur was sent to the Philippines. For two years he worked at building a military force that might be capable of defending the islands with American help. On Aug. 6, 1937, he was notified that he would be returned shortly for duty in the United States. Stating that his task in the Philippines was not yet completed, he retired from the Army.

Manuel Quezon, the Philippines Commonwealth President, then appointed him Field Marshal of the Philippines. Exercising the privileges of rank, General MacArthur designed the gold leaf-encrusted garrison cap that, along with sunglasses and a corncob pipe, was to become his trademark.

As the possibility of war grew, the Philippine Army was merged with the United States Army under the command of General MacArthur, who was restored to duty with the American forces as a lieutenant general on July 27, 1941. In December he was made a full general 11 days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

That attack was followed by a Japanese attack on military installations in the Philippines. A hardened, well-equipped Japanese force landed on Luzon and struck toward the fortified United States military base on Bataan Peninsula.

General MacArthur commanded 12,000 Philippine scouts and 19,000 United States troops. Added to this force were about 100,000 partly equipped Filipinos. The Japanese rolled the American forces into the Bataan Peninsula, where it was hoped they could hold out for 14 months.

General MacArthur assured his troops that aid would be forthcoming, although he had been given no such assurances by Washington. Word of his promises to his troops reached President Roosevelt, who was reportedly incensed.

Meanwhile, the Japanese tightened the noose around Bataan. As General MacArthur directed the defense from the labyrinthine, underground fortifications of Corregidor, orders came to him on Feb. 22 to leave his command in the hands of Lieut. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright and proceed to Australia.

Bidding farewell to the troops before boarding a PT boat, General MacArthur uttered a phrase that was to be added to his trademarks: “I shall return.”

Arriving in Melbourne, the general began agitating Washington with demands for more men and equipment, seeming not to comprehend that the war in Europe held priority. He dreamed of relieving Corregidor up to the very moment of its capitulation on May 5, 1942.

As the initiative in the Pacific Theater swung toward the Americans, he longed to fulfill his pledge.

On Oct. 30, 1944, General MacArthur waded ashore at Leyte and proclaimed: “I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil.”

On Dec. 18, 1944, he was promoted to the newly created rank of General of the Army. His forces went on to Manila, which fell Feb. 25, 1945. Okinawa fell in July. The next month, the doom of Japan was sealed with the dropping of the atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

On Sept. 2, 1945, Japanese representatives boarded the battleship U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay to sign the unconditional surrender. Attired in morning coat and top hat, a representative of Emperor Hirohito walked to the document table. It appeared that he intended to read the surrender document before signing it.

“Show him where to sign,” the General ordered Lieut. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, his Chief of Staff.

In swift strokes, the occupation instituted reforms that shook the roots of an ancient class society. All precedent was shattered and Japanese traditionalists were appalled when the Emperor, believed by Japanese to be divine, went to pay his respects to the American general.

Of the occupation, General MacArthur made this observation:

“The pages of history in recording America’s 20th-century contributions may, perchance, pass over lightly the wars we have fought. But, I believe they will not fail to record the influence for good upon Asia which will inevitably follow the spiritual regeneration of Japan.”

But the apparent serenity of Asia was shattered on June 25, 1950, when North Korean troops who had been trained and equipped by Russians swept southward across the 38th parallel in a lightning effort to overwhelm the inadequate South Korean forces, who were being trained by a small United States military advisory team.

President Truman ordered General MacArthur to take whatever steps he thought necessary to evacuate the Americans from South Korea. The civilians were evacuated by sea and air. The advisory troops remained with the Korean units.

The unequal struggle between the highly trained North Korean Communist Army of 500,000 and the ill-prepared South Korean Army of slightly more than 100,000 men soon involved scattered units of American troops, swept up hastily from scattered bases in the Far East.

The United States appealed to the United Nations. Since the Soviet Union was at that moment boycotting the Security Council for other reasons and was not present to use its veto, the U.N. decided to join forces with the South Koreans and the United States.

On Sept. 12, 1950, General MacArthur executed a daring strike from the sea on the North Korean rear and flank with an amphibious landing at the western port of Inchon. North Korea’s defense broke and the remnants of its army fled in disorder across the 38th parallel. General MacArthur announced that the war was virtually over, except for the need to pursue the enemy to the Yalu River, the border between Communist China and North Korea.

Unit commanders were in favor of pursuing the enemy northward without delay. However, orders were held in abeyance as word came that there was grave consternation at United Nations headquarters as to whether the intent of the combined effort had been to repel the invaders or rid the entire peninsula of Communist military forces.

On Oct. 10, President Truman, concerned with the General’s propensity for independent action, flew to Wake Island for a meeting. General MacArthur said there was “very little” chance that the Chinese Communists or the Soviet Union would react to a venture into North Korea.

General MacArthur returned to Tokyo and began to “close out” the Korean War. Near the end of October, United States paratroopers were dropped at two points just north of the North Korean capital of Pyongyang to cut off fleeing and disorganized Communist units. United Nations ground troops slashed across the 38th parallel in a dash to the Yalu River.

But elements identified as Chinese Communist troops were found south of the 38th parallel. They had crossed the Yalu in mid-October. General MacArthur’s intelligence officers had apparently failed to attach any significance to the reports of their presence.

By the second week in November full-scale warfare had begun and the United Nations forces were giving ground. General MacArthur let it be known that he was displeased with high decisions to refrain from attacking outside Korea lest the war spread.

In April, 1951, he was relieved of command by President [Harry S.] Truman. On April 17, the general, his wife and son arrived in San Francisco. In city after city, the General was greeted like a conquering hero.

Addressing Congress on April 19, he ended with a quotation from an old army song: “Old soldiers never die—they just fade away.”