JOSEPH PULITZER

April 10, 1847–October 29, 1911

CHARLESTON, S.C.—Joseph Pulitzer, proprietor of The New York World and St. Louis Post-Dispatch, died aboard his yacht, the Liberty, in Charleston Harbor this afternoon. The immediate cause of death was heart disease.

Mrs. Pulitzer, who had been sent for, reached the yacht shortly before her husband died.

Joseph Pulitzer’s career was a striking example of the opportunities that have been found in the United States for advancement from penury and friendlessness to wealth and power. Few who have come here to find their fortunes have been more handicapped at the start. He was without funds, had no acquaintances in this country, did not know the language, and suffered from defective vision which harassed him all his life. Yet at 31, thirteen years after landing at Castle Garden, he was the owner of a daily newspaper and on the road to riches.

Mr. Pulitzer’s influence on the development of modern American journalism has been large. In the first issue of The St. Louis Post-Dispatch he gave expression to those ideals as follows:

“The Post and Dispatch will serve no party but the people; will be no organ of Republicanism, but the organ of truth; will follow no caucuses but its own convictions; will not support the Administration, but criticise it; will oppose all frauds and shams wherever and whatever they are; will advocate principles and ideas rather than prejudices and partisanship.”

In assuming proprietorship of The New York World, Mr. Pulitzer said:

“There is room in this great and growing city for a journal that is not only cheap but bright, not only bright but large, not only large but truly democratic—dedicated to the cause of the people rather than that of purse potentates—devoted more to the news of the New than the Old World; that will expose all fraud and sham; fight all public evils and abuses; that will serve and battle for the people with earnest sincerity.”

Joseph Pulitzer was born in Budapest [in what was then Austria-Hungary] in 1847. His father was a businessman, but when he died, while Joseph was still a boy, it was found that the estate was very small. Joseph determined to enter the army, but he was rejected because of the defect in one eye.

The Civil War was in progress in this country, and he decided to come here. He landed at Castle Garden in 1864 practically penniless. He knew nobody in this country and could speak only a dozen words of English.

However, men were badly needed in the Union Army. The young Austrian was enrolled and served to the end of the war.

When he was mustered in New York City, another Austrian suggested that they go West to seek their fortunes. They went to a railroad ticket office, threw down all the money they had between them, and asked for passage as far West as their capital would take them. It was thus by chance that Mr. Pulitzer went to St. Louis.

He eventually began to study law, and in 1868 he was admitted to the bar. He practiced for a short time, but the profession was too slow for him. He looked about for some manner of life in which he could bring all his suppressed energies into immediate play. He found it in journalism.

He became a reporter for the Westliche Post, a German paper edited by Carl Schurz. His first appearance in this capacity was described by one who was at the time a reporter on an English paper:

“I remember his appearance distinctly, because he apparently had dashed out of the office upon receiving the first intimation of whatever was happening, without stopping to put on his coat or collar. In one hand he held a pad of paper and in the other a pencil. He did not wait for inquiries, but announced that he was the reporter for The Westliche Post, and then he began to ask questions of everybody in sight. I remember to have remarked to my companions that for a beginner he was exasperatingly inquisitive. The manner in which he went to work to dig out the facts, however, showed that he was a born reporter.”

Mr. Pulitzer’s chief ambition seemed to be to root out public abuses and expose evildoers. In this he was absolutely fearless.

This was 1868, and before the year was over he had risen to city editor and later to managing editor. Still later he became part owner of the paper. In the meantime he had begun taking an active part in politics. In 1869 he was elected to the Missouri Legislature, though but 22 years old, and only five years after he had landed here penniless and ignorant of the language.

In 1874 he sold his interest in the paper and went abroad to complete his education.

During the bitter contest that followed the Tilden-Hayes campaign, Mr. Pulitzer served The New York Sun at Washington as special correspondent and editorial writer. His articles were of vitriolic brilliancy and appeared over his own name, a departure that was rare in those days.

He continued this work until 1878. In the Fall of that year he went to St. Louis, where The Evening Dispatch was to be sold at auction after a precarious existence of several years. Mr. Pulitzer bought it for $2,500. When he entered the office the next morning he was unable to find as much as a bushel of coal or a roll of white paper.

By impressing into service everybody within reach, he managed to get out an issue of 1,000 copies. He set to work at once with characteristic energy to improve the situation. At that time the journalistic field in the West was occupied almost exclusively by morning papers. There were two other afternoon papers in St. Louis, The Post and The Star. Within 48 hours he had absorbed the Post, and the first number of The Post-Dispatch, which afterward became an enormous success, was issued.

During this period his political activities continued. In 1884 he was elected to Congress from a New York district, though he resigned after a few months.

It was at this time that he bought The New York World from Jay Gould. The World had been started in June 1880 as a penny paper of blameless features, eschewing intelligence of scandals, divorces, and even dramatic news. Its backing was ample, but it failed to make money. Mr. Pulitzer took possession May 10, 1883.

By the adoption of methods similar to those he had employed in St. Louis, Mr. Pulitzer soon had The World on a paying basis. Of these beginnings The World itself recently said:

“He was unable to expend large sums of money in the gathering of news, for the very excellent reason that he did not have it to spend. He did instill life and energy into every department of the paper on the very first day of his proprietorship, and in no part was the change in the character of matter printed more noticeable than in the news columns. But it is a fact, patent to anyone who will turn over the files for that year, that the first impetus given to the new World came from the editorial page. To this Mr. Pulitzer gave his personal and almost undivided attention, and by this agency first impressed upon the public mind the fact that a new, vigorous, and potent moral force had sprung up in the community.”

Mr. Pulitzer had one of the most expensive households in America. He had a home on East 73rd Street, an estate at Bar Harbor, and another country place on Jekyll Island, off the Georgia coast. He also had a 1,500-ton steam yacht.

His blindness made it necessary for him to have a large personal staff. He could not read or distinguish the faces of those about him. He could only listen and think.

Mr. Pulitzer was married to Miss Kate Davis. He leaves five children.

Since attaining affluence, he gave considerable sums to philanthropy, chiefly in the cause of education. He gave to Columbia University an endowment of $1,000,000 for the establishment of a school of journalism, which it has been understood would be utilized after his death.

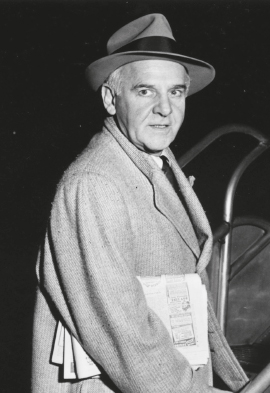

ADOLPH S. OCHS

March 12, 1858–April 8, 1935

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn.—Adolph S. Ochs, publisher of The New York Times, died here at 4:10 o’clock this afternoon amid the scenes of his first venture in publishing and his first professional triumphs. He was 77 years old.

Mr. Ochs suffered a cerebral hemorrhage while at lunch.

The end of the publisher’s long career came after he had visited the staff of The Chattanooga Times, whose success under his direction made that of The New York Times possible.

Mr. Ochs is survived by Mrs. Ochs; a daughter, Mrs. Arthur Hays Sulzberger; a brother, three sisters, and four grandchildren, Marian, Ruth, Judith and Arthur Ochs Sulzberger.

The story of Adolph S. Ochs is one of a career which, in poverty and wealth, obscurity and eminence, was all of one piece. The qualities that his employers noted when he began his newspaper career as a printer’s devil in Knoxville, Tenn., were qualities he manifested throughout his life. The principles he put into practice when at the age of 20 he took charge of a bankrupt small-town newspaper were the principles he put into practice 18 years later when he took charge of the bankrupt New York Times and carried it to influence and prosperity.

He believed in publishing only one kind of paper, and his great achievement was the proof that publishing that kind of paper—“clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial,” as he phrased it in his announcement in The Times on Aug. 18, 1896—could be both economically and ethically successful.

That he did so was due largely to the fact that he learned the newspaper business from the ground up. The poverty of his parents cut short his formal schooling; but the printing office was his high school and university, and something of the impress of the old-time printing shop and the old-school printers stayed with him all his life.

He was born in Cincinnati on March 12, 1858, eldest of the six children of Julius and Bertha Levy Ochs. Julius Ochs taught languages in various Southern schools.

After the war the family moved to Knoxville, but their fortunes did not prosper. Adolph, the oldest boy, went to work at the age of 11 as office boy to Captain William Rule, editor of The Knoxville Chronicle. He later became the paper’s printer’s devil, the old-time printer’s term for the boy who did the odd jobs about the composing room. He learned about the printing trade, and he learned fast.

But his eye was on Chattanooga, which was served by a single struggling newspaper, The Times. Discovering that Chattanooga had no city directory, Mr. Ochs set to work on this, his first publication. The directory not only made Mr. Ochs acquainted with Chattanooga, but made Chattanooga acquainted with Mr. Ochs.

The editor of The Times offered to sell it to Mr. Ochs for $800 if he would assume the paper’s debts. He borrowed $250 and bought a half interest in The Times, with the stipulation that he would have control of the paper. He became publisher on July 2, 1878.

The salutatory of the new publisher announced the theme around which his whole life was to be woven. The Times would get all the news it could, at home and abroad. But, it was added, “we shall conduct our business on business principles, neither seeking nor giving sops and donations.”

The young man had a newspaper plant fit for nothing but the junk heap, publishing a four-page paper with a circulation of 250. There was one reporter and a business office staff of one, and the proprietor and publisher was also business manager and advertising solicitor.

But the paper became successful, and two years after the publisher had bought the control of The Times, he bought the other half interest in the paper.

On Feb. 28, 1883, Mr. Ochs was married to Miss Effie Miriam Wise. To this union was born a daughter, Iphigene Bertha, who was married in 1917 to Arthur Hays Sulzberger.

All sorts of people passed through Chattanooga in the late eighties and early nineties. One was Harry Alloway, a Wall Street reporter for The New York Times, to whom Mr. Ochs remarked casually that he thought The Times offered the greatest opportunity in American journalism.

In 1896 Mr. Ochs received a telegram from Mr. Alloway. Since 1890 The Times had declined and there was talk of a reorganization. Alloway wired Mr. Ochs that if he were interested in The Times it could probably be bought cheap.

Mr. Ochs went to New York to investigate the situation. George Jones, who had joined with Henry J. Raymond in founding The New York Times in 1851 and had conducted it since Raymond’s death, had died in 1891. His heirs were now prepared to sell The Times.

As it turned out, only one purchaser was willing to pay the $1,000,000 they asked, a company under the presidency of Charles R. Miller, editor of The Times. Then the panic of 1893 struck. By the Spring of 1896 the circulation of The Times had dwindled to 9,000 and was losing $1,000 a day. A plan of reorganization was being formulated by Charles R. Flint and Spencer Trask, but the plan needed a man to work it.

In this situation the young publisher from Chattanooga came to town, and through Alloway arranged an interview with Mr. Miller. By the time the two men parted, Mr. Miller was convinced that The Times had found the man.

Mr. Ochs lacked the money to join the syndicate created by Mr. Flint and Mr. Trask. But Mr. Miller felt sure that Mr. Ochs could save the paper if he had a little time. A receiver kept The Times going while Mr. Ochs raised the needed funds, and the paper was transferred to him on Aug. 18, 1896.

Mr. Ochs himself bought $75,000 worth of bonds, carrying with them 1,125 shares of stock. Of the rest of the stock, 3,876 shares, enough to make an absolute majority, were put into escrow, to be delivered to the publisher when the paper had paid its way for three consecutive years. His control, however, was to be absolute from the first.

At the moment it seemed almost incredible that he could win. Dominating New York journalism of the period were The Herald, The World and The (morning) Journal, now The American; the former with a costly foreign service, the latter two wildly sensational, with immense circulations built up at a price of 1 cent, while the other morning papers, The Times included, sold for 3 cents.

To have imitated any of these competitors would have been suicidal; but Mr. Ochs would not have done it anyway. His salutatory announcement promised “to conduct a high-standard newspaper” for “thoughtful, pure-minded people,” emphasized by the adoption on Oct. 25, 1896, of the motto “All the News That’s Fit to Print,” which The Times carries to this day.

This definition of The Times’s purpose was Mr. Ochs’s own, and the phraseology was an emphatic announcement that The Times would not be what the nineties called a yellow newspaper. In place of the comic supplements of the yellows, The Times soon offered a pictorial Sunday magazine, and shortly after Mr. Ochs took charge, the Saturday Review of Books, later shifted to Sunday, became a permanent feature of the paper.

In the first year of Mr. Ochs’s proprietorship the circulation more than doubled, and the deficit, which had been $1,000 a day when he took charge, averaged less than a fifth of that at the end of the year. But there was still a deficit.

The Times steadily gained in circulation and advertising. But the deficit in Mr. Ochs’s second year was $78,000—larger than in the first year; the circulation had been pushed up to 25,000, but the advertising lineage of 1898 showed only a 10 percent gain over 1896. Something had to be done.

Mr. Ochs was advised to raise the price of the paper from 3 cents to 5 cents a copy. To the astonishment of all, Mr. Ochs proposed instead to cut the price to 1 cent.

This was to prove one of his most brilliant inspirations. Mr. Ochs believed that many people bought the “yellow journals” only because they cost a third as much as the other papers, and that they would buy a different sort of paper if they could get it for the same price.

The cut in price marked the beginning of victory. A year after the change the circulation of The Times had trebled, rising to 76,000, and for the most part it has been rising ever since.

Mr. Ochs’s third year as publisher showed a profit of $50,000, and from then on the success of The Times was assured. The original agreement had stipulated that the 3,876 shares held in escrow should be turned over to Mr. Ochs when he had made the paper pay for three successive years. On July 1, 1900, he had fulfilled this condition and became the owner of a majority stock interest in The Times, which he retained ever afterward.

The great fight of Mr. Ochs’s life was won, therefore, by 1900, and he won it by himself. He was the man who, as E. A. Bradford, a veteran of the editorial staff, put it, “found the paper on the rocks and turned them into foundation stones.”

That it kept on going up was due largely, in Mr. Ochs’s opinion, to the fact that most of the profits were plowed back into the business.

As The Times grew, Mr. Ochs seized upon every improvement in technique that would enable his paper to get the news more quickly and more fully and to get it to the reader in the best possible form and with the least possible lapse of time.

In 1896 The Times was still being published on Park Row. When this building became too small. Mr. Ochs resolved to build in what is now known as Times Square, and in January, 1905, the paper was moved uptown. In 1913, needing even more space, the paper migrated to the Times Annex at 229 West 43rd Street, just off the square.

In June, 1918, The Times received the first award of the Pulitzer Gold Medal for “disinterested and meritorious service” for publishing in full so many documents and speeches by European statesmen relating to the war. Advertising, circulation and the size of the paper had expanded greatly.

Mr. Ochs continued to direct The Times all his life. His town house was for many years at 308 West 75th Street, until in the Fall of 1931 he bought an estate in White Plains. He was a firm adherent of the reformed Jewish faith, and for many years he was a trustee of Temple Emanu-El in New York.

A charity close to Mr. Ochs’s heart was the collection of funds, each year at the Christmas season, for “The Hundred Neediest Cases.” This feature was inaugurated by him in 1912, when a fund of $3,630 was collected, to be distributed to persons chosen from lists furnished by the city’s leading charitable organizations. The appeal still is made solely through the publication of brief individual narratives in The Times.

WILLIAM RANDOLPH HEARST

April 29, 1863–August 14, 1951

By Gladwin Hill

BEVERLY HILLS, Calif.—William Randolph Hearst, founder of a vast publishing empire, and one of the most controversial figures in American journalism and politics, died today of a brain hemorrhage at his home here. His age was 88.

Although an invalid for four years, the publisher had kept in intimate touch with the operation of his 18 newspapers and other enterprises virtually up to the time of his death.

Mr. Hearst lapsed into a coma Sunday from which he did not recover. He died at 9:50 A.M., Pacific daylight time, in the house at 1007 North Beverly Drive to which he had retired from his fabulous San Simeon castle and ranch in mid-California when illness overtook him.

At his bedside were his five sons, William Randolph Jr., publisher of The New York Journal-American; David, publisher of The Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express; Randolph, publisher of The San Francisco Call-Bulletin; George and John; also Martin F. Huberth, chairman of the board of the Hearst Corporation; Richard E. Berlin, president of the corporation, and Dr. Myron Prinzmetal, Mr. Hearst’s physician.

They were joined by Marion Davies, former motion-picture star, who had long been a friend and confidante of the publisher.

Mr. Hearst’s wife, Mrs. Millicent Willson Hearst, from whom he had been separated for more than two decades, was at her home in New York.

Mr. Hearst was credited with keeping in day-to-day touch with the content and operations of his transcontinental newspaper chain, rewarding accomplishments handsomely and meting out sharp and acute criticism of blunders. His surveillance was close enough so that within the last week the word had passed among his Los Angeles staffs that “the chief,” as he was known among his employees, had waxed wrathful about something.

His interest in world affairs had remained equally lively. The last of the many campaigns and crusades he conceived, inspired and directed, a number of which have taken their place in American history, was his newspapers’ leadership of the movement in defense of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur after his dismissal from his Pacific command.

It was also generally understood that the publisher had such a strong aversion to the anticipation of death that even the staffs of his downtown papers had hesitated to make detailed plans for the inevitability. Support was lent to this by the fact that The Herald and Express altered the introduction of its story of his death between editions.

The first said “William Randolph Hearst, whose career as a publisher spanned more than half a century and ushered in the modern era of American journalism, died today.” The second version was: “William Randolph Hearst is dead. The greatest figure in American journalism, whose patriotism and wisdom had been a strongly guiding influence on the nation during a career that began more than a half century ago, died today.”

Mr. Hearst’s body was flown to his native San Francisco.

At the height of his career, William Randolph Hearst was one of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful newspaper owners. His newspapers frequently fought the battles of the common man, for whose attention they competed by means of comic strips, scandal, society gossip, pseudo-science, jingoism and political invective.

The term “yellow journalism,” generally believed to have derived from one of the early Hearst comic strips, “The Yellow Kid,” was coined to apply to Mr. Hearst’s newspaper practices.

At the peak of his influence he engendered the heat of controversy more than almost any other American. He bitterly opposed the participation of the United States in the European phases of both World Wars, and his sympathies until this country entered the conflicts seemed to lie with Germany.

Mr. Hearst led his newspapers in fights for many causes usually considered progressive. These included the eight-hour working day, direct election of United States Senators, woman suffrage, postal-savings banks, anti-trust legislation and municipal ownership of certain types of public utilities. He fought communism and government graft violently on all occasions.

Where his newspapers frequently were raucous and rowdy, Mr. Hearst himself was quiet and even shy. For years he lived in remote splendor after the manner of a feudal lord, but he liked to believe that he never lost the common touch.

Despite the great influence of his newspapers, Mr. Hearst never was able to achieve his ambition to hold high elective office. He had to be content with two uneventful terms in the House of Representatives.

Mr. Hearst’s newspaper campaigns were spectacular and exercised a profound effect on measures before Congress. As much as any other single man he was responsible for the defeat of resolutions to make the United States a party to the World Court covenant.

When Mr. Hearst was a child, his father acquired great wealth, and when Mr. Hearst’s mother was told at the beginning of her son’s newspaper-owning career that he was losing a million dollars a year, she is reported to have replied:

“That’s too bad; at that rate Willie can hold out for only 30 years.”

Mr. Hearst was born on the southeast corner of California and Montgomery Streets, San Francisco, on April 29, 1863. It was the year of Gettysburg and Vicksburg in the East, but in the West the raw frontier that was to shape much of Mr. Hearst’s thinking was awaiting the Midas touch of such men as George Hearst, his father, who was to amass a fortune—much of it in gold mine speculations—and become a United States Senator.

As a boy and young man, William Randolph Hearst was a bit of a handful. His doting father called him Buster Billy. After leaving the local schools, the youth made a brief appearance at St. Paul’s School, Concord, N.H., and private tutors completed his preparation for Harvard.

He already was interested in journalism, and he took the moribund college comic magazine, The Lampoon, and put it on its financial feet. When the university authorities failed to appreciate one of young Mr. Hearst’s practical jokes, he left Harvard in 1885 without taking a degree.

On March 4, 1887, Mr. Hearst’s name appeared on the editorial page of a newspaper for the first time, he, then 23, having persuaded his father to let him try his hand at running The San Francisco Examiner, which the elder Hearst had acquired for a bad debt.

The noisy battle later on in New York between Mr. Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of The World, for circulation began when Mr. Hearst bought the failing Morning Journal on Oct. 7, 1896, with $180,000 of his mother’s money. Mr. Pulitzer soon felt the weight of this 33-year-old Californian with the college clothes who had a habit of executing a few dance steps when he felt good.

In three months the circulation of The Journal jumped from 20,000 to 150,000. Mr. Hearst dropped The Journal’s price to one cent, and Mr. Pulitzer was compelled to do the same. Not only did Mr. Hearst threaten The World’s circulation, but he raided Mr. Pulitzer’s high-class staff for some of his ablest craftsmen.

William McKinley became President on March 4, 1897, and war with Spain became a distinct possibility. Mr. Hearst saw in the insurrection then occurring in Cuba the makings of spectacular newspaper copy. In August, Karl Decker, a Hearst agent, engineered the escape of Evangelina Cisneros, a Cuban woman of 18, from a Cuban prison, and she was brought to New York as proof of Spanish brutality.

Mr. Hearst played the loudest horn in the war clamor that heated public frenzy to a cherry red. When the United States declared war on Spain on April 24, 1898, Mr. Hearst became a national figure.

In 1903 Mr. Hearst was elected to the House of Representatives, where he stayed for two terms. He was frequently absent from roll call.

Mr. Hearst was 41 years old in 1904, when his name was presented for the Presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis. His nomination was seconded by Clarence Darrow, famous liberal attorney of Chicago. Mr. Hearst received 200 votes, 20 of them from California delegates. The nomination went to Judge Alton B. Parker, who got 658 votes and was then defeated decisively by Theodore Roosevelt.

Mr. Hearst ran unsuccessfully for Mayor of New York against George B. McClellan on the ticket of the Municipal Ownership League in 1905. Undaunted, Mr. Hearst ran for Governor of New York State in 1906 against Charles Evans Hughes, but lost after a bitter struggle.

In 1909 Mr. Hearst made his last attempt to win elective office when he ran for Mayor of New York against William J. Gaynor. He was decisively defeated.

Mr. Hearst’s political prestige in New York received a blow from which it never recovered in 1922, when Alfred E. Smith refused to run on a Democratic ticket with him, his anger aroused by stories and cartoons picturing him as a tool of the milk trust.

Mr. Hearst enjoyed a brief moment of power in 1932 when he helped to clinch the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt for his first term as President at the Democratic national convention in Chicago. But scarcely had Mr. Roosevelt been installed in the White House the following March when political warfare broke out between the President and the publisher. The President’s “New Deal” became the “Raw Deal” in all Hearst newspapers and was bitterly denounced.

Mr. Hearst was one of the first newspaper publishers to recognize the possibilities of motion pictures, though he was reported to have lost more than $2,000,000 in his ventures. In 1913 a company that he owned screened “The Perils of Pauline,” an interminable cliff-hanger featuring Pearl White. Mr. Hearst’s attempts to make a leading American movie star out of a striking New York blonde whose screen name was Marion Davies were successful.

In 1922 Mr. Hearst probably was at the height of his fame and power as a newspaper publisher. He owned 20 newspapers in 13 cities of the country and it is likely that at that time he was making more money than any publisher ever had made. His expenditures were fabulous. It is doubtful whether any American citizen ever had lived on so lavish a scale. His 240,000-acre ranch at San Simeon, with its 50 miles of oceanfront, was crowned by a great mansion and three vast guest houses, all of which at one time were filled with works of art and one of the world’s greatest collections of curios.

On April 30, 1903, Mr. Hearst married Miss Millicent Willson in Grace Protestant Episcopal Church, New York. Five sons were born to the marriage—George, William Jr., John, David and Randolph.

Legends clustered about Mr. Hearst, but none was as strange as the truth. His achievements as a collector would have made him unique if he had done nothing else. He acquired Etruscan tombs, California mountain ranges, herds of yak, Elizabethan caudle cups, Crusaders’ armor, paintings, tapestries, a knocked-down and crated Spanish abbey or two, 15th-century choir stalls, dozens of Mexican bridles, several Egyptian mummies and hundreds of other items, many of which he never saw.

H. L. MENCKEN

September 12, 1880–January 29, 1956

BALTIMORE—H. L. Mencken was found dead in bed early today.

The 75-year-old author, editor, critic and newspaper man had lived in retirement since suffering a cerebral hemorrhage in 1948.

Mr. Mencken, one of the leading American satirists, essayists and journalists of any day, exerted a tremendous influence on American letters between about 1910 and the middle Nineteen Thirties. The period of his strongest influence was relatively brief, but it had about it a quality of intensity that later generations found hard to understand.

Mr. Mencken blew a blast of fresh air into the somewhat musty American literary scene, particularly in the Nineteen Twenties. He directed the attention of the American reading public to a group of distinguished writers clamoring for greater recognition that included Sinclair Lewis, Theodore Dreiser, D. H. Lawrence, James Branch Cabell, Joseph Conrad, Ford Maddox Ford, Sherwood Anderson, Edgar Lee Masters and James Joyce.

Although not a formally trained scholar, Mr. Mencken made considerable contributions to philology by his studies in the American language. He used to say that he was not a scholar but a “scout for the scholars.”

Appearing on the literary scene with menacing agility in the pre–World War I period, Mr. Mencken laid about him with a cudgeling style of writing calculated to inflict severe lacerations and contusions on the American middle classes. His admirers cared little if this style was one that practically precluded temperate and objective discussion. He once wrote:

“The plain fact is that I am not a fair man and don’t want to hear both sides. On all subjects, from aviation to xylophone playing, I have fixed and invariable ideas.”

At the height of his influence Mr. Mencken was the bright hero of the young intellectuals. They carried about with them as badges of distinction, first The Smart Set and somewhat later, The American Mercury, publications edited by Mr. Mencken and George Jean Nathan. A whole generation of young newspapermen cocked their feet on desks and roared with laughter as they read the green-covered Mercury, in which Messrs. Mencken and Nathan thwacked the residents of the so-called “Bible Belt.”

Mr. Mencken’s lively comment on American life was delivered in a tone of omniscience that was probably responsible for a decline in his vogue during the Depression of the Thirties. He frequently had used the Sinclair Lewis character of George F. Babbitt as the standard of the American bourgeois mind.

But when the Depression was under way it became apparent even to Mr. Mencken’s stanchest admirers that while Babbitt did not have the answers, neither did Mr. Mencken.

The attention of the young intellectuals began to settle upon new prophets more versed in the idiom of economics. Also, Mr. Mencken was of German ancestry and was strong for the German ideas of discipline and political orderliness. These ideas had become associated in many minds with the activities of Adolf Hitler in the German Reich.

All his life Henry Louis Mencken remained steeped in the cultivated literary, musical, eating and drinking traditions of old Baltimore, where he was born Sept. 12, 1880. His father was August Mencken, a prosperous cigarmaker whose father had migrated from Saxony. His mother, Anna Margaret Abhau Mencken, was a celebrated Baltimore beauty of her day.

Mr. Mencken graduated from Baltimore Polytechnic Institute at the head of his class. Baltimore Poly was only a high school, and he never had a university education. On Jan. 16, 1899, he went to work as a police reporter on The Baltimore Morning Herald.

The young newspaper man spent his spare time discovering for himself such writers as George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen, and in writing supercharged short stories as well as verses in the manner of Rudyard Kipling.

By 1903 he was city editor of The Herald, and in 1906 he went to The Baltimore Sun, with which he was associated on and off during much of his career. He began to free-lance assiduously, and his name began to appear in print with fair regularity.

Theodore Dreiser, whose literary career was to owe much to Mr. Mencken at a later date, has left a keen word picture of the Mencken of this period. He recalled him as a “taut, ruddy, snub-nosed youth… whose brisk gait and ingratiating smile proved to be at once enormously intriguing and amusing. I had, for some reason not connected with his basic mentality, you may be sure, the sense of a small town roisterer or a college sophomore of the crudest yet most disturbing charm and impishness who, for some reason, had strayed into the field of letters.”

Two important things happened to Mr. Mencken on May 8, 1908. He got a part-time job writing about books for The Smart Set, and he met Mr. Nathan, the new Smart Set dramatic critic with whom his literary life was to be linked for many years.

In 1914 Mr. Mencken and Mr. Nathan became co-editors of The Smart Set. During the period of their association with this magazine, many of the most important new writers in America made their first appearances in the publication. The two men-about-town conducted their collaboration in an atmosphere of highly literate horseplay.

It was not always easy sledding in the business department, however. When Joseph Conrad’s literary agent in London cabled asking $600 for one of Conrad’s stories, Mr. Mencken replied, “For $600 you can have Smart Set.”

The entrance of the United States into World War I forced prices for newsprint and labor out of sight and dealt the coup de grâce to The Smart Set. Alfred A. Knopf backed Mr. Mencken and Mr. Nathan in The American Mercury, which appeared for the first time with the January, 1924, issue.

Nearly all the writing in The American Mercury was vivid and distinctive, and some of it was regarded by critics as distinguished. Mr. Mencken and his associates lavished loving care on “Americana,” one of the departments brought over from The Smart Set.

This was a miscellany of notes and clippings from provincial newspapers. It was used to demonstrate Mr. Mencken’s theory that the American middle-class mind was a dreadful affair.

A typical item might deal with the hearty and extroverted doings at a businessmen’s luncheon in Kansas. Or perhaps a group of clergymen being presented with black cravats by a silk manufacturer while a choir sings “Blest Be the Tie that Binds.”

Mr. Mencken’s literary style was vivid and violent. He urged the intelligentsia to “have at” the “booboisie” of the “hinterland,” and he delighted in the use of such words as “swinish” and “hoggish.”

The Mercury printed articles by such non-professional writers as Ernest Booth, a convicted bank robber. The frequency with which unlikely persons had their writings printed in The Mercury inspired a magazine of humor to publish a picture of two tramps sitting on a park bench. One of them is saying to the other:

“I enjoyed your little piece in The Mercury.”

Mr. Mencken, an implacable enemy of the New Deal, was a conservative Baltimorean all his life in spite of the lusty warfare that he waged on prudery and sham. His savage attacks on Prohibition caused those favoring these legal enactments to picture Mr. Mencken as a beer-guzzling rake. Actually, Mr. Mencken was a moderate drinker; most of his tippling was done in print rather than at the bar.

The quintessence of all that Mr. Mencken belabored in American life manifested itself in 1925 in Dayton, Tenn., when John Thomas Scopes went on trial for teaching high school students “certain theories that deny divine creation of man, as taught in the Bible; and did teach instead thereof that man was descended from the lower order of animals.”

At the trial Mr. Mencken was in the press seats to report with savage joy the verbal mauling of William Jennings Bryan, special prosecutor, by Clarence Darrow, defense attorney. Mr. Scopes was convicted and fined $100.

Mr. Nathan dropped out of The American Mercury in 1930 and three years later Mr. Mencken severed his connections with the magazine. The magazine had less than 30,000 circulation when Mr. Mencken left. Its peak circulation under Messrs. Mencken and Nathan had been 90,000.

After reporting the 1948 election campaign for The Baltimore Sun papers, Mr. Mencken suffered a stroke from which he never fully recovered.

Mr. Mencken, a great lover of words, kept records during his career of many Americanisms that he later listed in what he called, “The American Language.” It is generally agreed that these philological researches have formed an important basis for more exhaustive studies along the same lines.

Mr. Mencken long ago wrote this epitaph for himself:

“If after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.”

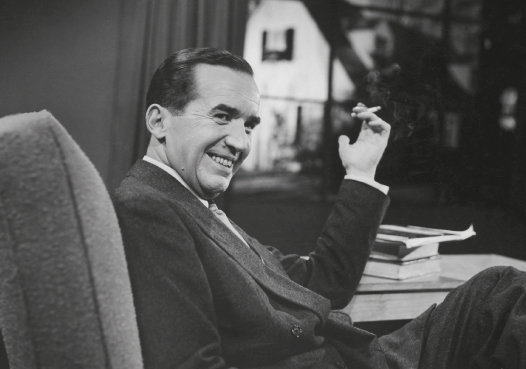

EDWARD R. MURROW

April 25, 1908–April 27, 1965

Edward R. Murrow, whose independence and incisive reporting brought heightened journalistic stature to radio and television, died yesterday at his home in Pawling, N.Y., at the age of 57.

The former head of the United States Information Agency had been battling cancer since October, 1963.

The ever-present cigarette (he smoked 60 to 70 a day), the baritone voice and the high-domed, worried face were the trademarks of the radio reporter who became internationally famous during World War II with broadcasts that started, “This… is London.” Later, on television, his series of news documentaries, “See It Now,” on the Columbia Broadcasting System from 1951 to 1958, set the standard for all television documentaries on all networks.

Mr. Murrow, who lived on a 280-acre farm, is survived by his widow, Janet, a son, and two brothers.

Mr. Murrow’s career with C.B.S., which spanned 25 years, ended in January, 1961, when President Kennedy named him head of the United States Information Agency. In October, 1963, a malignant tumor made the removal of his left lung necessary, and three months later he resigned.

Mr. Murrow achieved distinction first as a radio correspondent, reporting from London in World War II, and then as a pioneer television journalist opening the home screen to the stimulus of controversy. No other figure in broadcast news left such a strong stamp on both media.

His independence was reflected in doing what he thought had to be done on the air and worrying later about the repercussions among sponsors, viewers and stations.

In the last war, Mr. Murrow conveyed the facts with a compelling precision. But he went beyond the reporting of the facts. By describing what he saw in detail, he sought to convey the moods and feelings of war. In one memorable broadcast he said that as he “walked home at 7 in the morning, the windows in the West End were red with reflected fire, and the raindrops were like blood on the panes.”

Had a London street just been bombed out? The young correspondent was soon there in helmet, gray flannel trousers and sports coat, quietly describing everything he saw against the urgent sound patterns of rescue operations. Or he would be in a plane on a combat mission, broadcasting live on the return leg and describing the bombing he had watched as “orchestrated hell.”

He flew 25 missions in the war, despite the opposition of top C.B.S. executives in New York, who regarded him as too valuable to be so regularly risked. In the endless German air raids on London, his office was bombed out three times, but he escaped injury.

For a dozen years, as radio’s highest paid newscaster, he was known to millions of his countrymen by voice alone, a baritone tinged with an echo of doom. Then television added an equally distinctive face, with high-domed forehead and deep-set, serious eyes.

As the armchair interviewer on “Person to Person,” Mr. Murrow carried out a gentlemanly electronic invasion of the homes of scores of celebrities in the nineteen-fifties, from Sophie Tucker through Billy Graham.

From 1951 to 1958 Mr. Murrow also did a series of news documentaries under the title “See It Now.” In the 1953–54 season the telecast studied the impact of the emotional and political phenomenon known as “McCarthyism.” Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, Republican of Wisconsin, was then conducting his crusade against alleged Communist influence, but television had given the matter gingerly treatment.

Mr. Murrow and his long-time co-editor, Fred W. Friendly, broke this pattern decisively on Tuesday evening, March 9, 1954. Using film clips that showed the Senator to no good advantage, the two men offered a provocative examination of the man and his methods. The program, many thought, had a devastating effect. “McCarthyism” lost public force in succeeding months.

Egbert Roscoe Murrow was born on April 25, 1908, at Pole Cat Creek, N.C. He changed his first name to Edward in college. His father, a tenant farmer, moved to Blanchard, Wash., where his son grew up.

In 1930 Mr. Murrow graduated from Washington State College, and in 1935, he was employed by C.B.S. as director of talks and education. Then in 1937, he received an unexpected call from headquarters asking if he would go to Europe.

His answer—“yes”—was the decisive turn of his career.

Mr. Murrow, then 29, became the network’s one-man staff in Europe. He arranged cultural programs and interviewed leaders, and though his office was in London, he traveled extensively.

As war began to seem inevitable, he hired William L. Shirer, a newspaperman, to cover the Continent. He and Mr. Shirer were arranging musical broadcasts when Hitler marched into Austria.

Mr. Murrow flew to Berlin and chartered a Lufthansa transport to Vienna, arriving in time to watch the arrival of goose-stepping German troops. For 10 days he was allowed to broadcast, and he described the nation’s swift transition to a subject state. At home, millions hung on his and Shirer’s words.

As news chief for C.B.S. in Europe he hired the men who were to become the network’s famous roster of war correspondents—among them Eric Sevareid, Charles Collingwood, Howard K. Smith and Richard Hottelet.

Mr. Murrow’s wartime broadcasts from Britain, North Africa and finally the Continent gripped listeners by their firm, spare authority. He was the first Allied correspondent inside the Nazi concentration camp at Buchenwald. Near 300 bodies, he saw a mound of men’s, women’s and children’s shoes.

“I regarded that broadcast as a failure,” he said. “I could have described three pairs of those shoes—but hundreds of them! I couldn’t. The tragedy of it simply overwhelmed me.”

Returning to the United States in 1946, he became a vice president of C.B.S. in news operations. He was away from the microphone for 18 months. Then on Sept. 29, the former war correspondent went on the air with his evening radio report, “Edward R. Murrow with the News.” It was carried by 125 network stations to an audience of several million people weeknights for 13 years.

His sign-off on both radio and television was a crisp “Good night, and good luck.”

WALTER WINCHELL

April 7, 1897–February 20, 1972

LOS ANGELES—Walter Winchell, the fast-talking song-and-dance man who became a newspaper columnist and popular newscaster on radio, died today of prostate cancer at the U.C.L.A. Medical Center. He was 74.

—The Associated Press

By Alden Whitman

In the 20 years of his heyday, from 1930 to 1950, Walter Winchell was the country’s best-known and most widely read journalist as well as among its most influential.

Millions read “On Broadway,” his daily syndicated column that appeared locally in the old Daily Mirror. More millions listened to his weekly radio broadcasts. “WW,” as he often styled himself, purveyed a mélange of intimate news about personalities, mostly in show business and politics; “inside” items about business and finance; bits and pieces about the underworld; denunciations of Italian and German Fascism; diatribes against Communism; puffs for people, stocks and events that pleased him.

Although Mr. Winchell was often demonstrably inaccurate or hyperbolic, he was implicitly believed by many of his readers and auditors. In clumsier hands, his “news” might not have had much impact, but he imparted a certain urgency and importance to what he wrote and said by the frenetic and almost breathless style of his presentation.

In Winchellese, a person could start life as “a bundle from Heaven,” attend “moom pitchers” in his youth, then be “on the merge” or “on fire” and “middle-aisle it” or be “welded” to a “squaw.” Later on, the couple might “infanticipate” and be “storked.”

Although Mr. Winchell was often thought lacking in taste, he had friends in high and low places. Among those in exalted places were President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Mr. Winchell kept the President supplied with the latest Broadway jokes, and Mr. Roosevelt countered with news tidbits and encouragement for the columnist’s vitriolic attacks on the “Ratskis,” his name for the German Nazis and their American followers. These attacks infuriated the Nazis, who publicly excoriated their author as “a new hater of the New Germany.” They also disquieted William Randolph Hearst, a Hitler admirer and Mr. Winchell’s boss.

Mr. Hoover and Mr. Winchell were frequent companions at Sherman Billingsley’s Stork Club, a restaurant the columnist single-handedly made famous.

In 1939, in one of the most spectacular episodes of his career, Mr. Winchell was able to arrange the surrender of Louis (Lepke) Buchalter, a New York gangster, to Mr. Hoover. The hoodlum was wanted in New York on capital charges and by the Federal Government for narcotics smuggling. He telephoned Mr. Winchell, offering to give himself up to Mr. Hoover if the columnist were present.

Mr. Winchell picked up the gangster on a Manhattan street corner and delivered him to Mr. Hoover a few blocks away.

“Mr. Hoover,” said the columnist, “this is Lepke.”

“How do you do,” said Mr. Hoover.

“Glad to meet you,” said the hoodlum.

In his prime, Mr. Winchell loved to respond to police and fire calls, often arriving at the scene first. His car, courtesy of the police, was outfitted with a siren and a red light.

At a crime scene, according to Bob Thomas’s authoritative “Winchell,” he “interviewed victims and interrogated suspects, some of whom spilled out confessions because of awe over meeting” the columnist.

Mr. Winchell lived and worked in a free-spending atmosphere to which he himself was immune. Save for a Westchester house he bought to please his wife, “he lavished money on nothing,” Mr. Thomas reported, adding:

“He hadn’t the slightest inclination to art and other possessions. He owned eight suits, no more. He lived with utmost simplicity in an apartment which was useful only for sleeping. Every restaurant and nightclub owner in New York was eager to entertain him.”

He kept his money in cash in bank vaults. On becoming a millionaire in 1937, he had the Colony Club cater him an elegant meal, which he ate alone.

The plates and napery of that lunch were far removed from the poverty in which the columnist was reared. Born in Manhattan on April 7, 1897, Walter was the elder son of Jacob and Janette Bakst Winchel—the son later added a second “L” to the name. Jacob left the family when Walter was young.

Walter picked up his first money as a newsboy. When he was 12 he made his debut in the entertainment world after getting a tryout as a singer. For two years, he toured with the Edwards revues in company with young George Jessel, Eddie Cantor, Lila Lee and Georgie Price. Walter had quit school in the sixth grade.

In 1915, Walter teamed in a vaudeville act with Rita Green. In World War I, Mr. Winchell served as an admiral’s receptionist in New York. Returning to second-rate vaudeville after the war, he began posting bulletins with gossip of the other entertainers.

Mr. Winchell and Miss Green were married in 1920—the union lasted two years—and he began to submit show business gossip columns to Billboard, an entertainment weekly, and later to The Vaudeville News, for which he went to work in 1922 as a reporter and advertising salesman. His column, “Stage Whispers,” attracted attention, and he became known around Broadway as a bright and eager and very brash hustler.

In his rounds, he met June Magee, a red-haired dancer, whom he married in 1923. She died in 1970, reunited with her husband after a long estrangement.

After about two years on The Vaudeville News, Mr. Winchell was hired by The Evening Graphic, a bizarre tabloid that had been founded in 1924 by Bernarr Macfadden, an eccentric millionaire, food faddist and physical culture advocate. He was paid $100 a week.

One day in 1925, Mr. Winchell sat down and typed out a clutch of gossip notes he had acquired. The first few items read:

“Helen Eby Brooks, widow of William Rock, has been plunging in Miami real estate.… It’s a girl at the Carter de Havens.… Lenore Ulric paid $7 income tax… Fanny Brice is betting on the horses at Belmont… S. Jay Kaufman sails on the 16th via the Berengaria to be hitched to a Hungarian… Report has it that Lillian Lorraine has taken a husband again…”

It was the prototype of Winchell columns for almost 40 years. Shortly “Your Broadway and Mine,” the column’s title then, was the backbone of The Graphic’s circulation.

Leaving The Graphic in 1929 after repeatedly clashing with editors, Mr. Winchell moved to The Mirror. His first column appeared there June 10, 1929, and he was paid $500 a week.

In later years, the columnist moved to the far right politically. He became a champion of Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and wrote screeching anti-Communist columns.

Mr. Winchell’s power started to wane in the late forties. Executives became more wary of him because he devoted so much time to feuds and vendettas. His column slipped from 800 papers to 175, and it virtually disappeared with the demise in 1963 of The Mirror.

Mr. Winchell, who had few friends, moved west in 1965 and for the last several years stayed at the Ambassador in Los Angeles. His son, Walter Jr., committed suicide in 1967.

KATHARINE GRAHAM

June 16, 1917–July 17, 2001

By Marilyn Berger

Katharine Graham, who transformed The Washington Post from a mediocre newspaper into an American institution and, in the process, transformed herself from a lonely widow into a publishing legend, died today in Boise, Idaho, where she had been hospitalized since being injured in a fall over the weekend. She was 84.

Mrs. Graham was one of the most powerful figures in American journalism and, for the last decades of her life, at the pinnacle of Washington’s political and social establishments—a position that this shy, diffident wife and mother never imagined she would, or could, occupy.

It was only after she succeeded her father and her husband as publisher that The Washington Post, a newspaper with a modest circulation and more modest reputation, moved into the front rank of American newspapers, reaching new heights when its unrelenting reporting of the Watergate scandal contributed to the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon in 1974. Mrs. Graham’s courage in supporting her reporters and editors through the long investigation was critical to its success.

A year before Watergate, she gave solid backing to The New York Times in a historic confrontation with the federal government when she permitted her editors to join in publishing the secret revelations about the war in Vietnam known as the Pentagon Papers.

Mrs. Graham capped her career when she was 80 years old in 1998 by winning a Pulitzer Prize for biography for her often-painful reminiscence, “Personal History.” Nora Ephron, in her review of this best-selling memoir in The New York Times Book Review, wrote of Mrs. Graham, “The story of her journey from daughter to wife to widow to woman parallels to a surprising degree the history of women in this century.”

She was born in New York City on June 16, 1917. Her father, Eugene Meyer, made his fortune on Wall Street and became the first president of the World Bank. Her mother, the former Agnes Ernst, was a tall, self-absorbed woman of intellectual and artistic ambition. She was scathingly critical and often harsh with her daughter, the fourth of five children.

Mrs. Graham remembered a solitary and lonely childhood in palatial houses in Mount Kisco, N.Y., and in Washington. Neither parent attended her graduation from the University of Chicago in 1938.

When Katharine was 16, no one thought to tell her that her father had bid $825,000 at public auction to buy the bankrupt Washington Post, a paper with a circulation of 50,000 that was losing a million dollars a year.

Washington, in 1939, was full of young people converging on the capital to work for the New Deal. Among them was Philip L. Graham of Florida, a brilliant lawyer and a clerk at the Supreme Court. Shy and insecure, Katharine Meyer could not believe her luck when he asked her to marry him. Mr. Graham soon accepted his father-in-law’s invitation to join The Post. He became associate publisher at 30 and publisher at 31. Mr. Meyer also arranged for him to hold more stock in the company than his daughter because, he explained to her, “no man should be in the position of working for his wife.”

Mrs. Graham was belittled and silenced by a husband she adored, the man she called “the fizz” in her life. When he drank too much, gave vent to his rage or frequently became ill, she attributed it to the pressure of his work and not to a serious emotional affliction that had not yet been identified.

Mr. Graham had his first breakdown in 1957. His recovery was slow, but he re-emerged into Washington life. In 1961, he negotiated the purchase of Newsweek magazine. He also added television stations to the company’s holdings.

Mrs. Graham was shattered when she discovered that her husband was having an affair with a Newsweek employee. But there was an added blow: she discovered he had developed a scheme to pay her off and take ownership of The Post, in which he already had controlling interest because her father had given him the majority of the Post’s class A shares.

But she resolved not to give her husband a divorce unless he gave up enough controlling stock to give her majority interest.

Mr. Graham became increasingly ill. Finally, his illness had a name, manic depression. In August 1963 he shot himself to death at their farm in Virginia.

As Mrs. Graham mourned, she sought ways to hold on to The Post. She wrote that she was startled when her friend Luvie Pearson, the wife of the columnist Drew Pearson, told her to run the paper herself. “Don’t be silly, dear. You can do it,” Mrs. Pearson told her. “You’ve got all those genes.… You’ve just been pushed down so far you don’t recognize what you can do.”

Mrs. Graham met with the paper’s directors and told them that The Post would not be sold and that it would remain in the family. She was elected president of the company, but she felt “abysmally ignorant” about how to proceed. She said she was embarrassed to talk to her own reporters, timid in dealing with the paper’s executives and uncomfortable with balance sheets. Both at The Post and in the wider journalistic community, Mrs. Graham was usually the only woman at meetings and dinners. The men hardly knew what to make of her.

Two years after taking over The Post, she appointed Benjamin C. Bradlee, Newsweek’s Washington bureau chief, as executive editor. They made a formidable team, propelling The Post into one of its most dynamic periods. It became a breezy, gutsy paper that investigated government with gusto. A saucy, impertinent Style section appeared. In 1969, still with trepidation, Mrs. Graham added the title of publisher to that of president of the Washington Post Company.

In June 1971, The New York Times started publishing the secret history of decision-making during the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers. After a few days, a federal judge put The Times under a temporary restraining order, the first time in American history that an order of prior restraint was imposed.

The Post scrambled and got its own copy. There was a crisis atmosphere, for the Washington Post Company was preparing an initial public offering of its stock, raising concerns that it could face retribution from federal regulators if it published the Papers while The Times was enjoined. Lawyers suggested waiting, fearing that the whole company was at stake. Mrs. Graham later wrote: “Frightened and tense, I took a big gulp and said, ‘Go ahead, go ahead, go ahead. Let’s go. Let’s publish.’”

When the issue got to the Supreme Court, the cases for The Times and The Post were heard together, and the justices voted, 6 to 3, against restraining publication on the ground of endangering national security. The vote is considered a major triumph for freedom of the press.

On June 17, 1972, five months before Nixon’s re-election, five men were caught breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex in Washington. The Post began an intense investigation by two little-known reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, that eventually connected the break-in to the White House.

In the course of the investigation, the licenses of two of the company’s television stations were challenged. Mrs. Graham was also threatened with unspecified retaliation if The Post published an article that said John Mitchell, when he was attorney general, had controlled a secret fund that was used to spy on the Democrats. Mr. Mitchell crudely warned Mr. Bernstein that “Katie Graham” would have a breast “caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.”

Mrs. Graham did not back down, and The Post’s reporting on Watergate was vindicated.

In time, Mrs. Graham became comfortable with her power. She started to entertain the political elite at her home in Georgetown. By her 70th birthday party her power was such that the humor columnist Art Buchwald said in his toast: “There is one word that brings us all together here tonight. And that word is ‘fear.’”

With the help of the women’s movement, Mrs. Graham said, she became more cognizant of the causes of her own insecurities and more aware of the problems of working women. She played a signal role in changing Washington mores when it became widely known that on one evening after dinner she had refused to join the ladies upstairs while the men discussed world affairs over brandy and cigars.

Besides her son, Donald, Mrs. Graham is survived by her daughter, Elizabeth Weymouth, known as Lally; her sons William and Stephen; a sister, Ruth Epstein; 10 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Mrs. Graham’s resolve on editorial questions often contrasted with indecisiveness on business matters. In the 1970’s, she remembered, she hired and dismissed top executives too often. But, to cut costs, she dealt firmly with The Post’s mechanical unions, and in October 1975 the pressmen went on strike. All 72 of the newspaper’s presses were vandalized to make it impossible to publish.

But Mrs. Graham won the battle, and by the end of 1981, The Post’s daily circulation had soared to 984,000 from 771,000.

Donald Graham succeeded his mother as publisher in 1979 and chief executive of the company in 1991. By then it was valued at nearly $2 billion.

Mrs. Graham stepped down as chairwoman in 1993, again to be succeeded by her son, but remained on the board as chairwoman of the executive committee.

She was on her way to a bridge game this weekend when she collapsed and never recovered. Her life ended the way she said she had wanted it to. “The only thing I think any of us want,” she once said, “is to last as long as we’re any good. And then not.”

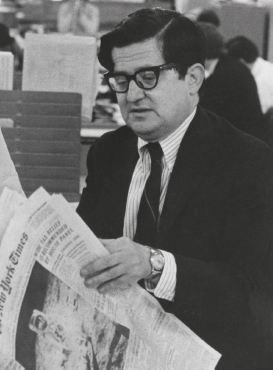

A. M. ROSENTHAL

May 2, 1922–May 10, 2006

By Robert D. McFadden

A. M. Rosenthal, a Pulitzer Prize–winning foreign correspondent who became the executive editor of The New York Times and led the paper’s global news operations through 17 years of record growth, modernization and major journalistic change, died yesterday in Manhattan. He was 84.

His death, at Mount Sinai Medical Center, came two weeks after he suffered a stroke, his son Andrew, who is the deputy editorial page editor of The Times, said. Mr. Rosenthal lived in Manhattan.

From ink-stained days as a campus correspondent at City College through exotic years as a reporter in Europe, Asia and Africa, Mr. Rosenthal climbed on rungs of talent, drive and ambition to the highest echelons of The Times and American journalism.

Brilliant, passionate, abrasive, a man of dark moods and mercurial temperament, he could coolly evaluate world developments one minute and humble a subordinate in the next. He spent almost all of his 60-year career with The Times.

As a reporter and correspondent for 19 years, he covered New York City, the United Nations, India, Poland and Japan, winning acclaim for his writing. The Pulitzer was for international reporting in 1960, for what the Communist regime in Poland, which had expelled him, called probing too deeply.

Returning to New York in 1963, he became an editor. Over the next 23 years, he served as metropolitan editor, assistant managing editor, managing editor and executive editor, enlarging his realms of authority by driving his staffs relentlessly, pursuing the news aggressively and outmaneuvering rivals for the executive suite.

Mr. Rosenthal directed coverage of the major news stories of the era—the war in Vietnam, the Pentagon Papers, the Watergate scandal and crises in the Middle East.

Publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 was a historic achievement for The Times. The papers, a 7,000-page secret government history of the Vietnam War, showed that every administration since World War II had enlarged America’s involvement while hiding the true dimensions of the conflict. But publishing the classified documents was risky: Would there be fines or jail terms? Would it lead to financial ruin for the paper?

The Nixon administration tried to suppress publication, and the case led to a landmark Supreme Court decision upholding the primacy of the press over government attempts to impose “prior restraint” on what may be printed. Major roles were played by Times staff members, among them Neil Sheehan, who had uncovered the papers. But it was Mr. Rosenthal as editor, arguing strenuously for publication, and Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, the publisher, who made the crucial decisions.

After 17 years as a principal architect of the modern New York Times, Mr. Rosenthal stepped down as the top editor in 1986 as he neared his job’s mandatory retirement age of 65. He then began nearly 13 years as the author of a column, “On My Mind,” for the Op-Ed page, in which he addressed topics with a generally conservative point of view. He surrendered it reluctantly.

Mr. Rosenthal’s life and career were chronicled closely, and his personal traits and private and professional conduct were analyzed with fascination in gossip and press columns, in magazines and books, and in the newsrooms and bars where those who had worked for or against him told their tales of admiration and woe.

The extraordinary interest was rooted only partly in the methods, achievements and faults of a powerful figure in journalism; it came, too, from the man himself: a table-pounding adventurer who shattered the stereotype of the genteel Times editor with his gut fighter’s instincts and legendary bouts of anger.

A gravel-voiced man with a tight smile, a shock of black hair and judgmental gray-green eyes behind horn-rimmed glasses, he was regarded by colleagues as complex, often contradictory. He saw himself as the guardian of tradition at The Times; but he presided over more changes than any editor in the paper’s history.

As managing editor from 1969 to 1977 and as executive editor until 1986, he guided The Times through a transformation that brightened its sober pages, expanded news coverage, launched a national edition, won new advertisers and new readers, and raised the paper’s sagging fortunes to unparalleled profitability.

By the end of the 1960’s, The Times, despite a distinguished journalistic history, had a clouded future. Its reporting and writing were regarded as thorough but ponderous. Revenues were declining, profits were marginal, and circulation was stagnant. Mr. Rosenthal’s objective was to erase a stodgy image and to improve readability and profitability while maintaining the paper’s character.

He expanded the weekday paper from two to four parts and inaugurated new weekday feature sections, innovations that were highly popular with readers and advertisers. He also began a series of Sunday magazine supplements and a national edition of The Times.

While many newspapers were struggling to stay alive, The Times prospered under Mr. Sulzberger and Mr. Rosenthal. Between 1969 and 1986, revenues of The New York Times Company soared, and net income rose to $132 million from $14 million. The Times and its staff members won 24 Pulitzers during Mr. Rosenthal’s years as editor.

Mr. Rosenthal, assisted by top lieutenants, including the deputy managing editor Arthur Gelb, who was his closest friend, decided which articles would appear here, thus helping to shape the perceptions of millions of readers, government and corporate policy makers and news editors across the country. He came to be regarded as the most influential newspaper editor in the nation, perhaps the world, with only Benjamin C. Bradlee of The Washington Post as a possible rival.

Press critics chronicled his rising fortune and the growing success of The Times. But they also described Mr. Rosenthal personally and as an administrator in generally unflattering terms and characterized his staff as rife with low morale.

Abraham Michael Rosenthal was born on May 2, 1922, in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, the son of Harry and Sarah Dickstein Rosenthal of Byelorussia. His father migrated to Canada in the 1890’s and became a fur trapper and trader.

The Rosenthals had six children, five of them girls. Abraham was the youngest. When he was a boy, the family moved to the Bronx.

In the 1930’s, a series of tragedies enveloped the family. Abraham’s father died of injuries suffered in a fall, and four of his sisters died. As a teenager, Abraham developed osteomyelitis, a bone-marrow disease, in his legs. It left him in acute pain, able to walk only with a cane or crutches. Because of the family’s poverty, he received inadequate medical treatment, and while encased in a cast from neck to feet he was told he might never walk again.

He was forced to drop out of DeWitt Clinton High School for a year. Accepted as a charity patient by the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, he underwent operations and eventually recovered almost completely.

He later enrolled at City College, joined the school newspaper and discovered that he liked, and was good at, reporting. In 1943, he became the campus correspondent for The Times. Editors eyed him as a promising young reporter, and in February 1944 he was hired as a staff reporter at 21. He quit City College to devote himself to his new job. After two years of local reporting, he was assigned to cover the United Nations, and his byline began to appear on the front page.

In 1954, Mr. Rosenthal was assigned to New Delhi and for the next four years covered the Indian subcontinent. He quickly established himself as an outstanding foreign correspondent. He was perceptive, aggressive, and could write on deadline with grace. In 1958, he was transferred to Warsaw and covered Poland and other nations of Eastern Europe for two years.

Mr. Rosenthal’s writing style was disarmingly personal: it was as if he had written a letter home to a friend. An article for The New York Times Magazine based on a visit to the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz, was typical.

“And so,” he wrote, “there is no news to report from Auschwitz. There is merely the compulsion to write something about it, a compulsion that grows out of a restless feeling that to have visited Auschwitz and then turned away without having said or written anything would be a most grievous act of discourtesy to those who died there.”

The 1959 dispatch that led to Mr. Rosenthal’s expulsion called the Polish leader, Wladyslaw Gomulka, “moody and irascible,” adding: “He is said to have a feeling of having been let down—by intellectuals and economists he never had any sympathy for anyway, by workers he accuses of squeezing overtime out of a normal day’s work, by suspicious peasants who turn their backs on the government’s plans, orders and pleas.”

His expulsion order charged: “You have written very deeply and in detail about the internal situation, party and leadership matters. The Polish government cannot tolerate such probing reporting.” Those phrases were cited by the Pulitzer committee when Mr. Rosenthal was awarded the prize for international reporting.

In 1963, after a two-year stint covering Japan, Mr. Rosenthal became an editor. His first assignment was command of a large, tradition-bound city news staff, not with the usual title of “city editor” but as “metropolitan editor,” reflecting new authority that he had demanded over a previously independent cultural news staff and a mandate for change throughout the newsroom.

He transformed the staff. Ignoring seniority, he began favoring the best writers, regardless of age; he began emphasizing investigative journalism and sent reporters out to capture the flavor and complexity of neighborhoods.

He encouraged his staff to abandon the stiff prose that had long characterized local news in The Times, and invited articles written with imagination, humor and literary flair. He assigned pieces on interracial marriage and other topics atypical for The Times.

One article assigned by Mr. Rosenthal, on New Yorkers’ fear of involvement in crime, recounted the murder of Kitty Genovese, a Queens woman whose screams were reportedly ignored by 38 neighbors while her killer attacked her on a street for 35 minutes.

Mr. Rosenthal was named assistant managing editor in 1966 and associate managing editor in 1968. Later, as managing editor and executive editor, he often traveled abroad and spoke publicly on freedom of the press.

He is survived by his first wife, Ann Marie Burke, from whom he was divorced, and their three sons. He is also survived by his second wife, Shirley Lord, and by a sister and four grandchildren.

Mr. Rosenthal’s final column for The Times was a summation of his life and career. He closed by saying that he could not promise to right all wrongs.

“But,” he wrote, “I can say that I will keep trying and that I thank God for (a) making me an American citizen, (b) giving me that college-boy job on The Times, and (c) handing me the opportunity to make other columnists kick themselves when they see what I am writing, in this fresh start of my life.”

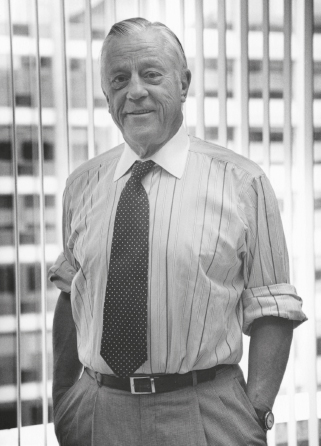

WALTER CRONKITE

November 4, 1916–July 17, 2009

By Douglas Martin

Walter Cronkite, who pioneered and then mastered the role of television news anchorman with such plain-spoken grace that he was called the most trusted man in America, died Friday at his home in New York. He was 92.

The cause was complications of dementia, said Chip Cronkite, his son.

From 1962 to 1981, Mr. Cronkite was a nightly presence in American homes and always a reassuring one, guiding viewers through national triumphs and tragedies alike, from moonwalks to war, in an era when network news was central to many people’s lives.

He became something of a national institution, with an unflappable delivery, a distinctively avuncular voice and a daily benediction: “And that’s the way it is.” He was Uncle Walter to many: respected, liked and listened to.

Along with Chet Huntley and David Brinkley on NBC, Mr. Cronkite was among the first celebrity anchormen.

Yet he was a reluctant star. He was genuinely perplexed when people rushed to see him rather than the politicians he was covering. He saw himself as an old-fashioned newsman—his title was managing editor of the “CBS Evening News”—and so did his audience.

As anchorman and reporter, Mr. Cronkite described wars, natural disasters, nuclear explosions, social upheavals and space flights, from Alan Shepard’s 15-minute ride to lunar landings. On July 20, 1969, when the Eagle touched down on the moon, Mr. Cronkite exclaimed, “Oh, boy!”

On the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Mr. Cronkite briefly lost his composure in announcing that the president had been pronounced dead at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. Taking off his black-framed glasses and blinking back tears, he registered the emotions of millions. It was an uncharacteristically personal note from a newsman who was uncomfortable expressing opinion.

“I am a news presenter, a news broadcaster, an anchorman, a managing editor—not a commentator or analyst,” he said in an interview in 1973.

But when he did pronounce judgment, the impact was large.

In 1968, he visited Vietnam and returned to do a rare special program on the war. He called the conflict a stalemate and advocated a negotiated peace. President Lyndon B. Johnson watched the broadcast, Mr. Cronkite wrote in his 1996 memoir, “A Reporter’s Life,” quoting a description of the scene by Bill Moyers, then a Johnson aide.

“The president flipped off the set,” Mr. Moyers recalled, “and said, ‘If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.’”

Mr. Cronkite sometimes pushed beyond the usual two-minute limit to news items. On Oct. 27, 1972, his 14-minute report on Watergate, followed by an eight-minute segment four days later, “put the Watergate story clearly and substantially before millions of Americans” for the first time, the broadcast historian Marvin Barrett wrote in “Moments of Truth.”

“From his earliest days,” David Halberstam wrote in “The Powers That Be,” his 1979 book about the news media, “he was one of the hungriest reporters around, wildly competitive, no one was going to beat Walter Cronkite on a story, and as he grew older and more successful, the marvel of it was that he never changed, the wild fires still burned.”

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. was born on Nov. 4, 1916, in St. Joseph, Mo., the son of Walter Sr., a dentist, and the former Helen Lena Fritsche.

As a boy, Walter peddled magazines door to door and hawked newspapers. As a teenager, after the family had moved to Houston, he got a job with The Houston Post as a copy boy and cub reporter.

Mr. Cronkite attended the University of Texas for two years, working on the school newspaper and picking up journalism jobs with The Houston Press. He left college in 1935 without graduating to take a job as a reporter with The Press.

While visiting Kansas City, Mo., he was hired by the radio station KCMO to read news and broadcast football games under the name Walter Wilcox. He was not at the games but received summaries of each play by telegraph, which provided fodder for vivid descriptions of the action.

At KCMO, Mr. Cronkite met an advertising writer named Mary Elizabeth Maxwell. The two read a commercial together. One of Mr. Cronkite’s lines was, “You look like an angel.” They were married for 64 years until her death in 2005.

In addition to his son, Walter Leland III, known as Chip, Mr. Cronkite is survived by his daughters, Nancy Elizabeth and Mary Kathleen, and four grandsons.

After being fired from KCMO in a dispute over journalism practices he considered shabby, Mr. Cronkite, in 1939, landed a job at the United Press news agency, now United Press International. He reported from Houston, Dallas, El Paso and Kansas City, and eventually became one of the first reporters accredited to American forces in World War II. He gained fame as a war correspondent, accompanying the first Allied troops into North Africa, reporting on the Normandy invasion and covering the Battle of the Bulge.

In 1943, Edward R. Murrow asked Mr. Cronkite to join his wartime broadcast team in CBS’s Moscow bureau. In “The Murrow Boys: Pioneers on the Front Lines of Broadcast Journalism,” Stanley Cloud and Lynne Olson wrote that Murrow was astounded when Mr. Cronkite rejected his $125-a-week job offer and decided to stay with United Press for $92 a week.

That year Mr. Cronkite was one of eight journalists selected for an Army Air Forces program that took them on a bombing mission to Germany aboard B-17 Flying Fortresses. Mr. Cronkite manned a machine gun until he was “up to my hips in spent .50-caliber shells,” he wrote.

After covering the Nuremberg war-crimes trials and then reporting from Moscow from 1946 to 1948, he again left print journalism to become the Washington correspondent for a dozen Midwestern radio stations. In 1950, Murrow successfully recruited him for CBS.