EUGENE O’NEILL

October 16, 1888–November 27, 1953

BOSTON—Eugene O’Neill, the noted American playwright whose prolific talents had brought to him both Nobel and Pulitzer Prizes, died today of bronchial pneumonia.

Mr. O’Neill, who was 65, had been ill for several years with Parkinson’s disease.

Mr. O’Neill, who died in a Boston apartment where he had been living recently, is survived by his third wife, Carlotta Monterey; a son, Shane, and a daughter, Oona O’Neill, the wife of the actor Charlie Chaplin.

Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was generally regarded as the foremost American playwright, his achievements in the theater overwhelming those of his ablest contemporaries. He came upon the scene at an opportune moment and remained active long after the American theater had come of age.

In the words of Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times, Mr. O’Neill shook up the drama as well as audiences and helped transform the theater into an art seriously related to life. The genius of Mr. O’Neill lay in raw boldness, in the elemental strength of his attack upon outworn concepts of destiny.

The playwright received the Pulitzer Prize on three occasions and was the second American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The author of 38 plays, most of them grim dramas in which murder, disease, suicide and insanity are recurring themes, Mr. O’Neill was in recent years too wracked by illness to write. He lived in a house by the sea with his third wife, a former actress.

But his plays continued to be produced to acclaim here and abroad, and the fall of 1951 saw a O’Neill “revival” on Broadway. The American National Theatre and Academy scheduled his “Desire Under the Elms” to launch its new season. The New York City Theatre Company played “Anna Christie” as the second offering of its winter season.

A revival of “Ah, Wilderness!,” the playwright’s nostalgic comedy of first love, found its way to the television screen.

No modern playwright except the late George Bernard Shaw had been more widely produced than Mr. O’Neill. He was as well known in Stockholm, Buenos Aires, Mexico City and Calcutta as in New York.

There was as much color and excitement in his early life as there was in his plays. Indeed, much of his success was attributable to the fact that he had lived in and seen the very world from which he drew his dramatic material.

As a young man he spent his days as a sailor and his nights in dives that lined the water’s edge. Out of these experiences came such plays as “The Hairy Ape,” “Anna Christie” and “Beyond the Horizon,” all of which have had a lasting life in the theater.

Mr. O’Neill was born on Oct. 16, 1888, in the Barrett House, a family hotel at 43rd Street and Broadway. His father was James O’Neill, who starred for so many years in “The Count of Monte Cristo.” His mother was the former Ellen Quinlan. The first seven years of Eugene’s life were spent trouping around the country with his parents.

On his eighth birthday he was enrolled in a Roman Catholic boarding school on the Hudson. In 1902, when he was 13, he entered Betts Academy in Stamford, Conn., then considered one of the leading boys’ schools in New England.

He was graduated in 1906 and went to Princeton. After 10 months at the university, he was expelled for heaving a brick through a window of the local stationmaster’s house. It marked the end of his formal education.

Shortly thereafter he went to Honduras with a young mining engineer, and the two spent several months exploring the country’s jungles and tried their hand at prospecting for gold. The venture ended after Mr. O’Neill became ill with fever and was shipped home.

For a time the young man worked as an assistant stage manager for his father, who was touring in a play called “The White Sister.” But he soon succumbed to the lure of far-off places and shipped as an ordinary seaman on a Norwegian freighter bound for Buenos Aires. This began his acquaintance with the forecastle that would stand him in good dramatic stead later on.

After Buenos Aires, he shipped again, this time for Portuguese East Africa. From there he sailed back to Buenos Aires, then worked his way to New York on an American ship.

In New York he lived at a waterfront dive known as Jimmy the Priest’s, and acquired the locale for “Anna Christie.” In August, 1912, he went to work as a reporter on The New London Telegraph in Connecticut. His newspaper career lasted for four months because, as he admitted, he was more interested in writing verse and swimming than in gathering news.

Just before Christmas in 1912 he developed tuberculosis and was sent to the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium at Wallingford, Conn., where he spent five months.

At Gaylord he began to read [August] Strindberg. “It was reading his plays,” Mr. O’Neill later recalled, “that, above all else, first gave me the vision of what modern drama could be, and first inspired me with the urge to write for the theater myself.”

After his discharge from the sanitarium he boarded with a family in New London for 15 months. During this period he wrote 11 one-act plays and two long ones. He tore up all but six of the one-acters. His father paid to have five of the six short plays printed in a volume called “Thirst,” published in 1914.

The elder O’Neill also paid a year’s tuition for his son at Prof. George Baker’s famous playwriting course at Harvard. Afterwards, Mr. O’Neill returned to New York and settled in a Greenwich Village rooming house, where he proceeded to soak up more “local color” at various Village dives, among them a saloon known as The Working Girls’ Home.

Mr. O’Neill lived in the Village until 1916, when he moved to Provincetown, Mass., and fell in with a group conducting a summer theatrical stock company known as the Wharf Theatre. He hauled out a sizable collection of unproduced and unpublished plays, one of which, a one-acter called “Bound East for Cardiff,” was put into rehearsal. It marked Mr. O’Neill’s debut as a dramatist.

At summer’s end the Wharf Theatre set up shop in New York and called itself the Provincetown Players, a name that was to become famous. The company produced more of Mr. O’Neill’s plays, and the budding playwright began to be talked about in theatrical circles farther afield. About the same time, three of his one-act plays, “The Long Voyage Home,” “Ile” and “The Moon of the Carribbees,” were published in the magazine Smart Set.

In 1918 Mr. O’Neill went to Cape Cod to live, occupying a former Coast Guard station on a lonely spit of land three miles from Provincetown. He started working on longer plays and, in 1920, had his first big year when he won the first of his three Pulitzer Prizes for “Beyond the Horizon.” The play marked Mr. O’Neill’s first appearance on Broadway. The other prize winners were “Anna Christie” in 1922 and “Strange Interlude” in 1928.

“Beyond the Horizon” established Mr. O’Neill as both a ranking playwright and a moneymaker. The play ran for 111 performances and grossed $117,071.

The Theatre Guild began producing his plays with “Marco Millions” in 1927 and staged all his plays thereafter. At least three of the plays, “Mourning Becomes Electra,” “Strange Interlude” and “The Iceman Cometh,” marked a new departure—they ran from four to five hours in length.

Mr. O’Neill’s dramas ranged from simple realism to the most abstruse symbolism, but one play—”Ah, Wilderness!”—was more in the tradition of straight entertainment and interspersed with sentiment. The play ran for 289 performances.

Mr. O’Neill did not always meet with approval. At times he was the object of bitter denunciation, especially from persons who believed his works smacked of immorality. By his choice of themes he several times stirred up storms that swept his plays into the courts.

“All God’s Chillun Got Wings” was fought by New York authorities on the ground that it might lead to race riots. “Desire Under the Elms” was almost closed in the face of mounting protests. It never did open in Boston. The play was permitted to go on in Los Angeles, but after a few performances the police arrested everybody in the cast.

“The Hairy Ape,” which starred Louis Wolheim in the role of Yank, a powerful, primitive stoker, was one of the dramatist’s most popular works. The play ran for 10 weeks, went on the road for a long tour and later was popular abroad.

Many critics felt that “Mourning Becomes Electra,” which opened on Oct. 26, 1931, and had 14 acts, was Mr. O’Neill’s masterpiece. Mr. Atkinson called it “heroically thought out and magnificently wrought in style and structure.” Joseph Wood Krutch observed that “it may turn out to be the only permanent contribution yet made by the 20th century to dramatic literature.”

After “Days Without End” was produced in 1934, a play that lasted only 57 performances, Mr. O’Neill was not represented on Broadway until 1946, when “The Iceman Cometh” was staged.

In 1936, he won the Nobel Prize but could not go to Stockholm to receive it because of an appendicitis operation.

In a letter to the prize committee, Mr. O’Neill said: “This highest of distinctions is all the more grateful to me because I feel so deeply that it is not only my work which is being honored but the work of all my colleagues in America—that the Nobel Prize is a symbol of the coming of age of the American theatre.”

After “The Iceman Cometh,” Mr. O’Neill wrote a play called “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” which will not be produced until 25 years after his death. He had shown the manuscript to a few friends, and it was reported that the play deals with his own family life.

Mr. O’Neill was stricken with Parkinson’s disease about 1947. The disease caused his hands to jerk convulsively, making it impossible for him to write in longhand.

In 1909 the dramatist married the former Kathleen Jenkins, who bore him a son, Eugene O’Neill Jr. The son committed suicide on Sept. 25, 1950. The marriage ended in divorce in 1912, and six years later, Mr. O’Neill married the former Agnes Boulton. They were divorced in 1929. Shane and Oona were born to this marriage. Mr. O’Neill married Miss Monterey on July 22, 1929.

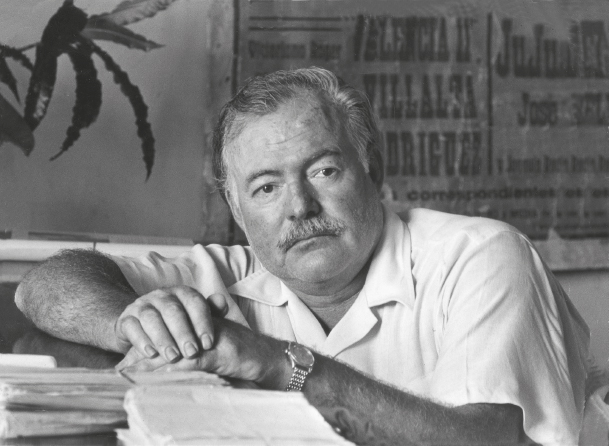

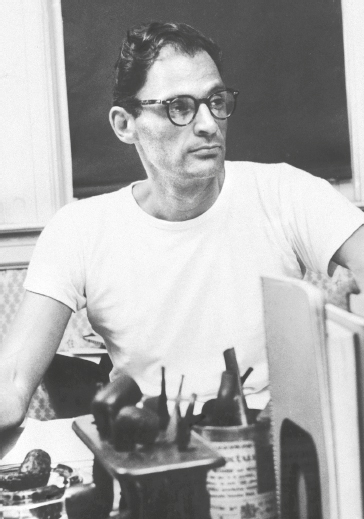

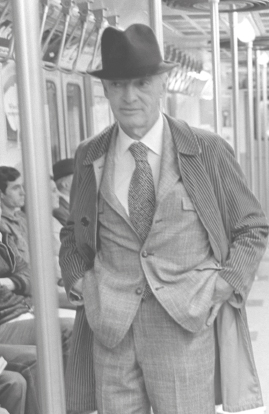

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

July 21, 1899–July 2, 1961

KETCHUM, Idaho—Ernest Hemingway was found dead of a shotgun wound in the head at his home here today. His wife, Mary, said that he had killed himself accidentally while cleaning the weapon.

Mr. Hemingway, whose writings won him a Nobel Prize and a Pulitzer Prize, would have been 62 years old July 21.

Frank Hewitt, the Blaine County Sheriff, said after a preliminary investigation that the death “looks like an accident,” adding, “There is no evidence of foul play.”

The body of the bearded, barrel-chested writer, clad in a robe and pajamas, was found by his wife in their modern concrete house in this village on the outskirts of Sun Valley. A double-barreled, 12-gauge shotgun lay beside him with one chamber discharged.

Mrs. Hemingway, the author’s fourth wife, was at the time of the shooting the only other person in the house and was asleep in a bedroom upstairs. The shot woke her and she went downstairs to find her husband’s body near a gun rack in the foyer. Mrs. Hemingway told friends that she had been unable to find any note.

Mr. Hemingway was an ardent hunter and an expert on firearms. His father, Dr. Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, who was also devoted to hunting, shot himself to death in 1928 at the age of 57, despondent over a diabetic condition. The theme of a father’s suicide cropped up frequently in Mr. Hemingway’s short stories and at least one novel, “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

As an adult, he sought out danger. He was wounded by mortar shells in Italy in World War I and narrowly escaped death in the Spanish Civil War when three shells plunged into his hotel room. In World War II, he was injured in a taxi accident. He nearly died of blood poisoning on one African safari, and he and his wife walked away from an airplane crash in 1954 on another big-game hunt.

The author, who owned two estates in Cuba and a home in Key West, Fla., started coming to Ketchum 20 years ago. His house sits on a hillside near the banks of the Wood River.

Mr. Hemingway achieved worldwide fame and influence as a writer by a combination of great emotional power and a highly individual style that could be parodied but never successfully imitated. His lean and sinewy prose; his mastery of a laconic, understated dialogue; his insistent use of repetition, often of a single word, built up and transmitted an inner excitement to countless of his readers. In his best work, the effect was accumulative; it was as if the creative voltage increased as the pages turned.

Not all readers agreed on Mr. Hemingway, and his “best” single work will be the subject of literary debate for generations. But possibly “The Old Man and the Sea,” published in 1952, had the essence of the uncluttered force that drove his other stories. In it, man is a victim of, and yet rises above, the elemental harshness of nature.

The short novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 1953, and it unquestionably moved the judges who awarded Mr. Hemingway the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year. A great deal of Mr. Hemingway’s work showed a preoccupation, frequently called an obsession, with violence and death. He loved guns, he was one of the great aficionados of the deadly bullfight, and he identified with the adventures of partisan warfare.

He wrote a great deal of hunting, fishing, and prizefighting, with directness, vigor, and the accuracy of a man who has handled the artifacts of a sport. He was at times a hard liver and a hard drinker, but he was also a hard and constant worker.

Mr. Hemingway’s fascination with the calibers of cartridges and physical conflict in general brought a barb from the writer Max Eastman in 1937. “Come out from behind that false hair on your chest, Ernest,” Mr. Eastman wrote. “We all know you.”

Mainly by trial and error, Mr. Hemingway had taught himself to write limpid English prose. Of his apprentice days as a writer in Paris, he wrote:

“I was trying to write then and I found the greatest difficulty, aside from knowing truly what you really felt, rather than what you were supposed to feel, and had been taught to feel, was to put down what really happened in action; what the actual things were which produced the emotion that you experienced.”

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born in Oak Park, Ill., a suburb of Chicago, on July 21, 1899, the second of six children. His father was a physician who was more devoted to hunting and fishing than to his practice and gave the boy a fishing rod when he was 3 and a shotgun when he was 10. His mother, Grace Hall Hemingway, was a religious-minded woman who sang in the choir of the First Congregational Church.

With his graduation from Oak Park High, Mr. Hemingway completed his formal education. He read widely, however, and had a natural facility for languages.

World War I was underway, and Mr. Hemingway managed to get to Italy, where he wangled his way into the fighting as a Red Cross ambulance driver with the Italian Army. He learned all about the great Italian rout at Caporetto, which he described brilliantly in “A Farewell to Arms,” published in 1929.

On July 8, 1918, while he was passing out candy to frontline troops at Fossalta di Piave, Mr. Hemingway was wounded in the leg by an Austrian mortar shell and hospitalized for many weeks. He eventually drifted to the expatriate Left Bank world of Paris and was soon one of the writers who frequented Shakespeare & Co., the bookstore of Sylvia Beach. Here he met, among many others, André Gide and James Joyce.

It was in Paris that Mr. Hemingway began to write seriously. He wrote with discernment about the persons around him, his expatriate countrymen, together with the “Lost Generation” British and European post-war strays, and he limned them with deadly precision.

Before he was established as a writer, Mr. Hemingway underwent the privations that were almost standard for young men of letters in Paris. He lived in a tiny room and often subsisted on a few cents’ worth of fried potatoes a day. With the publication in 1926 of “The Sun Also Rises” after three years of indifferent response to his work, he achieved sudden fame.

In 1928, Mr. Hemingway returned to the United States, where he lived for the next 10 years, mostly in Florida. He was still only 30 when he published his highly successful “A Farewell to Arms.”

“Death in the Afternoon” was published in 1932, and the book’s great success established its author as one of the great popularizers of bullfighting.

For several years Mr. Hemingway hunted big game in Africa and did much shooting and fishing in different parts of the world. “Winner Take Nothing” was published in 1933 and “The Green Hills of Africa” in 1935. The latter was one of the best contemporary accounts of the complex relationships between the hunter, the hunted and the African natives who are essential to the ritual of their confrontation.

Like many American intellectuals, Mr. Hemingway offered some degree of support to left-wing movements during the Nineteen Thirties. In “To Have and Have Not” (1937), one critic thought he had sounded “vaguely Socialist,” although more readers will remember the work as a tale of action and tragedy in the Florida Keys, the love affair between the doomed boatman and his slatternly wife.

In 1936, Mr. Hemingway went to Spain and covered the war for the North American Newspaper Alliance. In 1940 his novel of the Spanish Civil War, “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” showed that his own deepest sympathies were with the Loyalists.

The year World War II broke out, Mr. Hemingway took up residence in Cuba. But soon he was back in action in Europe, resuming the combat correspondence he had begun in Spain. He was with the first of the Allied armed forces to enter Paris, where, as he put it, he “liberated the Ritz” Hotel. Later he was with the Fourth United States Infantry Division in an assault in the Hurtgen Forest, winning the Bronze Star for his semi-military services in this action.

In 1950, critics were disappointed by “Across the River and into the Trees,” the story of a frustrated United States infantry colonel who goes to Venice to philosophize, make love and die. But two years later “The Old Man and the Sea” pleased virtually everyone. It relied on the elemental drama of a fisherman who catches the greatest marlin of his life, only to have it eaten to the skeleton by sharks before he can get it to port.

On Jan. 23, 1954, the writer and the fourth Mrs. Hemingway, the former Mary Welsh, figured in a double crash in Uganda, British East Africa. First reports said both had been killed. In fact, after one light plane crashed, a second had picked up the couple unhurt. Both Mr. Hemingway and his wife suffered injuries in the crack-up of the rescue plane.

Mr. Hemingway’s other published writings include “Three Stories and Ten Poems,” “In Our Time,” “The Torrents of Spring,” “Men Without Women,” and “The Fifth Column and First Forty-nine Stories.”

Mr. Hemingway earned millions of dollars from his work, partly because many of his stories and novels were adapted to the screen and television. These included “The Killers,” an early gangster story; “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” both set in East Africa; “The Sun Also Rises,” “A Farewell to Arms,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and “The Old Man and the Sea.”

Mr. Hemingway’s first wife was the former Hadley Richardson, whom he married in 1919. They were divorced in 1926. The next year Mr. Hemingway married Pauline Pfeiffer. This marriage ended with divorce in 1940, and that year Mr. Hemingway married a novelist, Martha Gellhorn. In 1946, after their divorce, Mr. Hemingway married Miss Welsh. Along with his wife, Mr. Hemingway is survived by a sister and three sons.

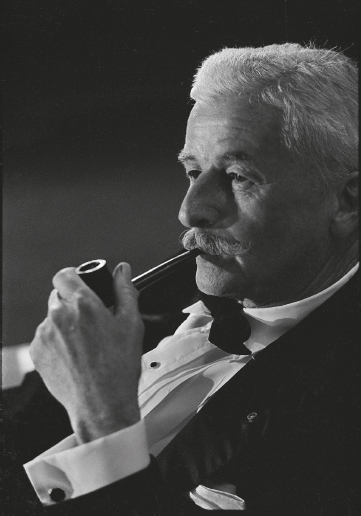

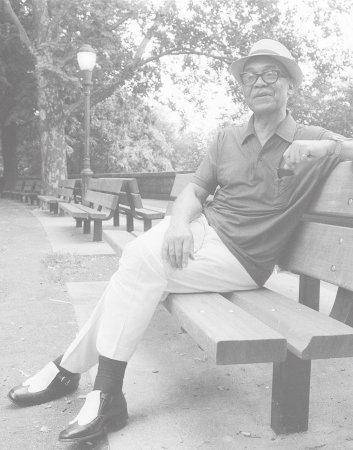

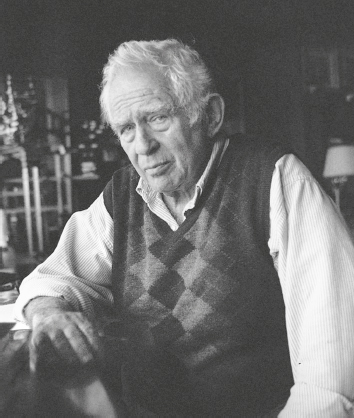

WILLIAM FAULKNER

September 25, 1897–July 6, 1962

OXFORD, Miss.—William Faulkner died of a heart attack today in this Mississippi town that he made famous in literature.

The author was 64 years old. His wife, Estelle, was at his bedside.

In recent years Mr. Faulkner had spent much of his time at the University of Virginia, where he was a lecturer on American literature. He and his wife returned last May to Oxford, a community of about 8,000 that Mr. Faulkner used as home base throughout his career.

President [John F.] Kennedy, leading the nation in tributes to the author, said: “Since Henry James, no writer has left behind such a vast and enduring monument to the strength of American literature.”

Mr. Faulkner won the Nobel Prize for 1949 for a series of novels in which he created his own Yoknapatawpha County in northern Mississippi. There he set his Gothic saga of decadent sophisticates, greedy landlords, and shrewd and brutal tenant farmers.

Mr. Faulkner won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1954 novel, “The Fable.”

His most famous novels were “Absalom, Absalom!” “Sartoris,” “The Sound and the Fury,” “As I Lay Dying,” “Sanctuary” and “Light in August,” and the trilogy “The Hamlet,” “The Town” and “The Mansion.” His most recent novel, “The Reivers,” was published June 4 to critical acclaim.

In addition to his widow, survivors include his daughter and two brothers.

A key to Mr. Faulkner’s genius was the faculty he possessed of thinking and writing in the vernacular of poor whites and Negroes of his section.

The tales of Yoknapatawpha, interwoven with rape, violence and sadism, repelled some readers to the extent that recognition in his homeland had to await acclaim from abroad.

—United Press International

The storm of literary controversy that beat about William Faulkner is not likely to diminish with his death. Many of the most firmly established critics of literature were deeply impressed by the stark and somber power of his writing. Yet many commentators were repelled by his themes and his prose style.

To the sympathetic critics, Mr. Falkner dealt with the dark journey and the final doom of man in terms that recalled the Greek tragedians. They found symbolism in the frequently unrelieved brutality of the yokels of Yoknapatawpha County, the imaginary Deep South region from which Mr. Faulkner drew the persons and scenes of his most characteristic works.

Actually, Yoknapatawpha was Lafayette County and Jefferson town was the Oxford on the red-hill section of northern Mississippi where William Faulkner was reared and where his family had been deeply rooted for generations.

While admitting that Mr. Faulkner’s prose sometimes lurched and sprawled, his admirers could point out an undeniable golden sharpness of characterization and description.

Of Mr. Faulkner’s power to create living and deeply moving characters, Malcolm Cowley wrote:

“And Faulkner loved these people created in the image of the land. After a second reading of his novels, you continue to be impressed by his villains, Popeye and Jason and Joe Christmas and Flem Snopes: but this time you find more place in your memory for other figures standing a little in the background yet presented by the author with quiet affection: old ladies like Miss Jenny DuPré, with their sharp-tongued benevolence; shrewd but kindly bargainers like Ratliff, the sewing machine agent, and Will Varner, with his cotton gin and general store.”

Mr. Faulkner was an acknowledged master of the vivid descriptive phrase. Popeye had eyes that “looked like rubber knobs.” He had a face that “just went away, like the face of a wax doll set too near the fire and forgotten.”

The apt phrases that Mr. Faulkner found for the weather and the seasons were cited by his admirers. There was the “hot pine-winey silence of the August afternoon,” “the moonless September dust, the trees not rising soaring as trees should but squatting like huge fowl,” “those windless Mississippi December days which are a sort of Indian summer’s Indian summer.”

Many critics contended that Mr. Faulkner served up raw slabs of pseudorealism that had little merit as serious writing. They said that his writings showed an obsession with murder, rape, incest, suicide, greed and depravity that existed largely in the author’s mind.

William Faulkner was born in New Albany, Miss., on Sept. 25, 1897.

The first Faulkners—the “u” is a recent restoration by William Faulkner—came to Mississippi in the Eighteen Forties. William Faulkner was the oldest child of Murray Falkner and Maude Butler Falkner. Murray Falkner ran a livery stable in Oxford and later became business manager of the University of Mississippi at Oxford.

In William Faulkner’s fiction the Sartoris clan is the Falkner family. The Sartorises are forced to make humiliating compromises with the members of the grasping and upstart Snopes family.

William Faulkner played quarterback on the Oxford High School football team but failed to graduate. Later he wrote: “Quit school to work in grandfather’s bank. Learned medicinal value of his liquor. Grandfather thought it was the janitor. Hard on the janitor.”

Oxford, where Mr. Faulkner grew up, is a typical Deep-South town. It has the traditional courthouse square flanked with statues of Confederate soldiers, and a quiet main street lined by one-story buildings and stores.

The 1949 motion picture “Intruder in the Dust,” based on Mr. Faulkner’s novel of that name, was filmed in Oxford.

The film depicted racial intolerance and bigotry in a small Southern community but had a “happy ending” in which an elderly, proud Negro accused of murder is saved from lynching by a white Southern lawyer with the help of a white boy and an elderly white woman. The movie was called “great” by Bosley Crowther, The New York Times critic.

Mr. Faulkner also said he had written a dozen movie scripts, most of them for his friend Howard Hawks, adding:

“He sent for me later to help adapt what Ernest Hemingway said was the worst book he ever wrote, ‘To Have and Have Not.’ Then I did another one, from that book by Raymond Chandler, ‘The Big Sleep.’ I also did a war picture, one I liked doing, ‘The Road to Glory,’ with Fredric March and Lionel Barrymore. I made me some money and I had me some fun.”

Back home, he was briefly a student at the University of Mississippi.

One who knew Mr. Faulkner as a student at the University of Mississippi is George W. Healy Jr., editor of The New Orleans Times-Picayune.

“I first knew Bill when he was postmaster at the University of Mississippi post office in 1922,” Mr. Healy said. “But Bill got fired as postmaster because he used the post office as a kind of men’s club. One day a post office inspector came in while a bridge game was in progress and a little while later Bill told us he was leaving.”

With the publication of “The Sound and the Fury” in 1929, Mr. Faulkner gave strong indications of being a major writer. The critics found in it something of the word-intoxication of James Joyce and the long, lasso-like sentences of Henry James.

“Sanctuary,” published in 1931, was Mr. Faulkner’s most popular and best-selling novel. It is about the harrowing experiences of a sensitive Southern girl, Temple Drake, who, like many Faulkner characters, reappears in another book, in this case “Requiem for a Nun.” One of Mr. Faulkner’s most memorable characters, Popeye, was created for “Sanctuary.”

Among Mr. Faulkner’s other notable books were “The Sound and the Fury” and “As I Lay Dying.” The former, described by one critic as “one of the few original efforts at experimental writing in America,” is told partly through the mind of an idiot named Benjy.

Mr. Faulkner lived and did most of his writing in Oxford in an old colonial house that he bought in 1930. He was a slightly built man who carried himself tensely, and when bothered or bored he could exhibit quick anger. He had thick iron-gray hair and a dark mustache. When he felt like it he could be charming and his manners were impeccable.

On one occasion, Bennett Cerf, head of Random House, Mr. Faulkner’s publisher, had taken the bourbon-sipping author to task for not answering his mail. Mr. Faulkner was said to have replied:

“Mr. Cerf, when I get a letter from you, I open it and shake it and if a check doesn’t fall out I tend to forget it.”

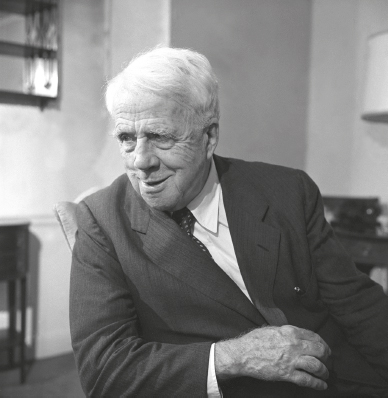

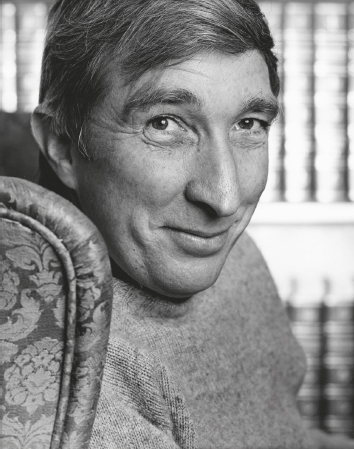

ROBERT FROST

March 26, 1874–January 29, 1963

BOSTON—Robert Frost, dean of American poets, died today at the age of 88.

He was pronounced dead at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital at 1:50 A.M. The cause was listed as “probably a pulmonary embolism,” or blood clot in the lungs.

Not long before his death, Mr. Frost had been dictating an article on Ezra Pound from his hospital bed when he fell asleep, according to his daughter, Leslie Frost.

—The Associated Press

Robert Frost was beyond doubt the only American poet to play a touching personal role at a Presidential inauguration; to report a casual remark of a Soviet dictator that stung officials in Washington, and to twit the Russians about the barrier to Berlin by reading to them, on their own ground, his celebrated poem about another kind of wall.

But it would be much more to the point to say he was also without question the only poet to win four Pulitzer Prizes and, in his ninth decade, to symbolize the rough-hewn individuality of the American creative spirit more than any other man.

Finally, it might have been even more appropriate to link his uniqueness to his breathtaking sense of exactitude in the use of metaphors based on direct observations (“I don’t like to write anything I don’t see,” he told an interviewer in Cambridge, Mass., two days before his 88th birthday.)

Thus he recorded timelessly how the swimming buck pushed the “crumpled” water; how the wagon’s wheels “freshly sliced” the April mire; how the ice crystals from the frozen birch snapped off and went “avalanching” on the snowy crust.

The incident of Jan. 20, 1961—when John F. Kennedy took the oath as President—was perhaps the most dramatic of Mr. Frost’s “public” life.

Invited to write a poem for the occasion, he rose to read it. But the blur of the sun and the edge of the wind hampered him; his brief plight was so moving that a photograph of former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mrs. Kennedy and Mrs. Lyndon Johnson watching him won a prize because of the deep apprehension in their faces.

But Mr. Frost was not daunted. Aware of the problem, he simply put aside the new poem and recited from memory an old favorite, “The Gift Outright,” dating to the nineteen-thirties. It fit the circumstances as snugly as a glove.

In 1962, Mr. Frost accompanied Stewart L. Udall, Secretary of the Interior, on a visit to Moscow.

A first encounter with Soviet children, studying English, did not encourage the poet. He recognized the problem posed by the language; it was painfully ironic, because he had said years before that poetry was what was “lost in translation.”

But a few days later, he read “Mending Wall” at a Moscow literary evening. “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” the poem begins. The Russians may not have got the subsequent nuances. But the idea quickly spread that the choice of the poem was not unrelated to the wall partitioning Berlin.

On Sept. 7, the poet had a long talk with Premier Khrushchev. He described the Soviet leader as “no fathead”; as smart, big and “not a coward.”

“He’s not afraid of us and we’re not afraid of him,” he added.

Subsequently, Mr. Frost reported that Mr. Khrushchev had said the United States was “too liberal to fight.” It was this remark that caused a considerable stir in Washington.

Explaining why he invited Mr. Frost to speak at his inauguration, President Kennedy said, “I think politicians and poets share at least one thing, and that is their greatness depends upon the courage with which they face the challenges of life.”

The President was echoing a cry that Mr. Frost had long made—the higher role of the poet in a business society. “Everyone comes down to Washington to get equal with someone else,” he told a Senate education subcommittee. “I want our poets to be declared equal to—what shall I say?—the scientists. No, to big business.”

Many years before, he told young writers gathered under Bread Loaf Mountain at Middlebury, Vt.:

“Every artist must have two fears—the fear of God and the fear of man—fear of God that his creation will ultimately be found unworthy, and the fear of man that he will be misunderstood by his fellows.”

These two fears were ever present in Robert Frost, with the result that his published verses were of the highest order and completely understood by thousands of Americans in whom they struck a ready response. To countless persons who had never seen New Hampshire birches in the snow or caressed a perfect ax he exemplified a great American tradition with his superb, almost angular verses written out of the New England scene.

His pictures of an abandoned cord of wood warming “the frozen swamp as best it could with the slow smokeless burning of decay,” or of how “two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference,” with their Yankee economy of words, moved his readers nostalgically and filled the back pastures of their mind with memories of a shrewd and quiet way of life.

Strangely enough, Mr. Frost spent 20 years writing his verses about stone walls and brown earth, blue butterflies and tall, slim trees without winning any recognition in America. It was not until “A Boy’s Will” was published in England and Ezra Pound publicized it that Mr. Frost was recognized as the indigenous American poet that he was.

In the years that followed, besides receiving the four Pulitzers, he was to be honored by institutions of higher learning and find it possible for a poet to earn enough money so that he would not have to teach or farm or make shoes or write for newspapers—all things he had done in his early days.

Like many another Yankee individualist, Mr. Frost was a rebel. He was the son of an ardent Democrat whose belief in the Confederacy led him to name his son Robert Lee. The father, William Frost, had run away from Amherst, Mass., to go West; Robert was born in San Francisco on March 26, 1874. His mother, born in Edinburgh, Scotland, emigrated to Philadelphia when she was a girl.

His father died when Robert was about 11. The boy and his mother, the former Isabelle Moody, went to live at Lawrence, Mass., with William Prescott Frost, Robert’s grandfather, who gave the boy a good schooling. Influenced by the poems of Edgar Allan Poe, Robert wanted to be a poet before he went to Dartmouth College, where he stayed only through 1892.

In the next several years he worked as a bobbin boy in the Lawrence mills, as a shoemaker and as a reporter for The Lawrence Sentinel. He attended Harvard in 1897–98, then became a farmer at Derry, N.H., and taught there. In 1905 he married Elinor White, also a teacher, by whom he had five children. In 1912 Mr. Frost sold the farm and the family went to England.

He came home to find the editor of The Atlantic Monthly asking for poems. He sent along the very ones the magazine had previously rejected, and they were published. The Frosts went to Franconia, N.H., to live in a farm house Mr. Frost had bought for $1,000. His poetry brought him some money, and in 1916 he again became a teacher. He was a professor of English, then “poet in residence” for more than 20 years at Amherst College. He spent two years in a similar capacity at the University of Michigan. Later Frost lectured and taught at The New School in New York.

In 1938 he retired temporarily as a teacher. Mrs. Frost died that year in Florida. Afterward, he taught intermittently at Harvard, Amherst and Dartmouth.

While critics heaped belated praise on his earthy, Yankee poems, there were also finely fashioned lyrics in which the man of the soil flashed fire with intellect. Such a poem was “Reluctance” with its nostalgic ending:

Ah, when to the heart of man was it ever less than treason

To go with the drift of things, to yield with a grace to reason,

And bow and accept the end of a love or a season?

Or:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Asked about his method of writing a poem, Mr. Frost said: “I have worried quite a number of them into existence, but any sneaking preference [I have had] remains for the ones I have carried through like the stroke of a racquet, club or headsman’s ax.”

In another interview he observed: “If poetry isn’t understanding all, the whole world, then it isn’t worth anything. Young poets forget that poetry must include the mind as well as the emotions. Too many poets delude themselves by thinking the mind is dangerous and must be left out. Well, the mind is dangerous and must be left in.”

T. S. ELIOT

September 26, 1888–January 4, 1965

LONDON—T. S. Eliot, the quiet, gray figure who gave new meaning to English-language poetry, died today at his home in London. He was 76 years old.

Eliot was an American who moved to England at the beginning of World War I and became wholly identified with Britain, even becoming naturalized in 1927.

The influence of Eliot began with the publication in 1917 of his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Perhaps his most significant contribution came five years later in the lengthy poem “The Waste Land.”

Eliot, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1948, was a convert to Anglo-Catholicism, and his religious belief showed up strongly in his later works.

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

These four lines by Thomas Stearns Eliot, written as the conclusion to “The Hollow Men” in 1925, are probably the most quoted lines of any 20th-century poet writing in English. They are also the essence of Eliot as he established his reputation as a poet of post–World War I disillusion and despair.

They were written by an expatriate from St. Louis, a graduate of Harvard College, who had chosen to live in London and who was working as a bank clerk.

Together with “The Waste Land,” published three years earlier, these works established Eliot as a major poet. From there he went on to fame and financial independence, but he always remained, in the layman’s view, the poet of gray melancholy.

Eliot’s early poems did not represent the more mature conclusions of his later years about the state of mankind and the world, as stated in “The Four Quartets,” or his delicious sense of humor, whose subjects included himself:

How unpleasant to meet Mr. Eliot!

With his features of clerical cut.

And his brow so grim

And his mouth so prim…

Whereas Eliot began his seminal “The Waste Land” with the line “April is the cruellest month” and ended it 434 lines later with “Shantih shantih shantih,” his more seasoned reflections included these lines from “The Four Quartets”:

And right action is freedom

From past and future also.

For most of us, this is the aim

Never here to be realized;

Who are only undefeated

Because we have gone on trying;

We, content at last

If our temporal reversion nourish

(Not too far from the yew-tree)

The life of significant soil.

Not only did Eliot shift his philosophic outlook, but his poetic accents also became almost conversational.

In appearance he was an unlikely figure for a poet. Eliot was a stooped man of just over 6 feet who had a prim appearance which mingled with a slight air of anxiety.

He lacked flamboyance or oddity in dress or manner, and there was nothing of the romantic about him. His habits of work were equally “unpoetic,” for he eschewed bars and cafes for the bourgeois comforts of an office with padded chairs and a well-lighted desk.

Eliot’s attire was a model of the London man of business. He wore a bowler and often carried a tightly rolled umbrella. His accent, which started out as pure American Middle West, became over the years quite upper-class British.

The poet was born on Sept. 26, 1888, into a family that had a good background in the intellectual, religious and business life of New England.

He entered Harvard in 1906 in the class that included Water Lippmann, Heywood Broun, and John Reed. He completed his undergraduate work in three years and took a Master of Arts degree in his fourth. Although he never took his doctorate, he completed the dissertation in 1916.

His Harvard classmates recall that he dressed with the studied carelessness of a British gentleman, smoked a pipe and liked to be left alone. This aspect of Eliot was hardly altered when he briefly returned to Harvard in the nineteen-thirties as a sort of poet in residence.

In that sojourn he lived in an undergraduate house near the Charles River and entertained students at teas. The tea was always brewed and he poured with great delicacy, his long fingers clasping the handle of the silver teapot. The quality of his tea, the excellence of the petit fours and the rippling flow of his conversation drew overflow crowds of students.

Eliot was an omnivorous reader. He consumed philosophy, languages and letters, and this lent his poetry an erudition and scholarship unmatched in this century. He footnoted “The Waste Land” as though it were a doctoral thesis.

He had a strong dislike for most teaching of poetry, and once recalled that he had been turned against Shakespeare in his youth by didactical instructors.

“I took a dislike to ‘Julius Caesar’ which lasted, I am sorry to say, until I saw the film of Marlon Brando and John Gielgud,” he said, “and a dislike to ‘The Merchant of Venice’ which persists to this day.”

In 1915 Eliot became a teacher in the Highgate School in London, and the next year went to work in Lloyds Bank, Ltd.

In London, Eliot lived in a comfortable apartment in Chelsea overlooking the Thames. In 1915, he married Miss Vivienne Haigh-Wood, who died in 1947. In 1957, Eliot married Miss Valerie Fletcher, his private secretary. He was then 68 and his bride about 30.

Eliot’s association with the “little” magazines—those voices of protest against the Establishment—began when he was assistant editor of Egoist from 1917 to 1919.

He established The Criterion, a literary publication that never had a circulation exceeding 900. Later he was an editor for Faber & Faber.

The first poem that started Eliot’s reputation was “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” in 1917. In it he assumed the pose of a fastidious, world-weary, young-old man, aging into ironic wit. The poem is full of exquisitely precise surrealist images and rhythms, but it also has everyday metaphors. Part of it goes:

I grow old… I grow old…

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind?

Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers and walk upon the beach.

Eliot’s strictures on applying concentrated efforts to the understanding of poetry could well apply to his next major poem, “The Waste Land.” Heavily influenced by Ezra Pound, “The Waste Land” was an expression of gigantic frustration and despair.

The poem, a series of somewhat blurred visions, centers on an imaginary waste region, the home of the Fisher King, a little-known figure in mythology, who is sexually impotent. The work made his reputation.

Eliot was regarded as an important literary critic as well as a poet. His first book, “The Sacred Wood,” was published in 1920.

It is possible that Eliot is most widely known through his drama “Murder in the Cathedral,” a sardonic account of the murder of Thomas à Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170.

Two of Eliot’s plays enjoyed critical success in London and New York. “The Cocktail Party,” published in 1954, was a story of deeply religious experience told against a background of highly literate and amusing British people. “The Confidential Clerk” told of bastardy and general unhappiness.

In his lighter moments Eliot was an unabashed ailurophile. He kept cats at home, bestowing upon them such names as Man in White Spats; he also wrote a book of poems called “Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats.”

These lines from “The Naming of Cats” illustrate Eliot’s profound insight into the narcissistic world of the feline:

But I tell you, a cat needs a name that’s particular.

A name that is peculiar, and more dignified,

Else how can he keep up his tail perpendicular.

Or spread out his whiskers, or cherish his pride?

. . . When you notice a cat in profound meditation,

The reason, I tell you, is always the same:

His mind is engaged in rapt contemplation

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name;

His ineffable effable

Effeineffable

Deep and inscrutable singular Name.

Those critical of Eliot’s writing accused him of obscurity for its own sake. They found his verses full of coy and precious mannerisms. They accused him of loading down his writing with obscure references that could be known only by a few intimate friends.

Yet no man between the two World Wars so dominated his time as critic and creator. This expatriate American caught and expressed in his verse the sense of a doomed world, of fragmentation, of a wasteland of the spirit that moved the generation after the war.

It was a generation that felt tricked by the politicians, felt that the enormous bloodletting of World War I had been a fraud and saw in the disintegrating Europe of their time the symbol of their own lives. Their mood of spiritual despair was exquisitely rendered in Eliot’s poetry.

The dry tone, the arid physical and spiritual landscape of his early poetry, and the bleakness that stared out of his verse summed up for a generation their own sense of defeat and barrenness. They echoed his words, “I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker.”

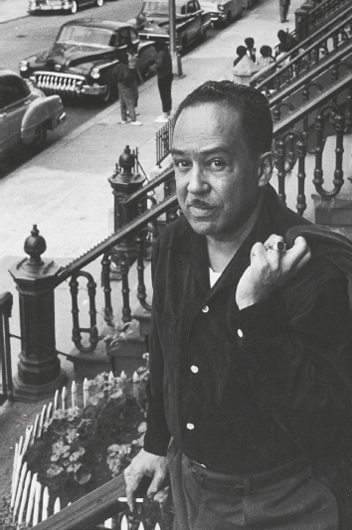

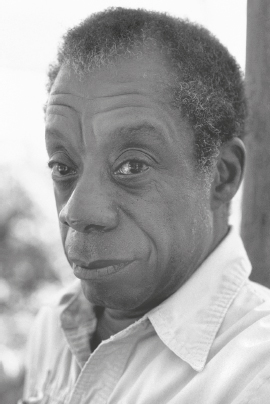

LANGSTON HUGHES

February 1, 1902–May 22, 1967

By Thomas Lask

Langston Hughes, the noted writer of novels, stories, poems and plays about Negro life, died last night in Polyclinic Hospital [in Manhattan] at the age of 65.

Mr. Hughes, who died of congestive heart failure, was sometimes characterized as the “O. Henry of Harlem.” He was an extremely versatile and productive author who was well known for his folksy humor.

In a description of himself written for “Twentieth Century Authors,” Mr. Hughes wrote:

“My chief literary influences have been Paul Laurence Dunbar, Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman. My favorite public figures include Jimmy Durante, Marlene Dietrich, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Marian Anderson and Henry Armstrong.”

“I live in Harlem, New York City,” he continued. “I am unmarried. I like ‘Tristan,’ goat’s milk, short novels, lyric poems, heat, simple folk, boats and bullfights; I dislike ‘Aida,’ parsnips, long novels, narrative poems, cold, pretentious folk, buses and bridges.”

It was said that whenever Mr. Hughes had a pencil and paper in his hands, he would scribble poetry. He recalled an anecdote about how he was “discovered” by the poet Vachel Lindsay.

Lindsay was dining at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington when a busboy summoned his courage and slipped several sheets of paper beside the poet’s plate. Lindsay was annoyed, but he picked up the papers and read a poem titled “The Weary Blues.”

As Lindsay read, his interest grew. He called for the busboy and asked, “Who wrote this!”

“I did,” replied Langston Hughes.

Lindsay introduced the youth to publishers, who brought out such works as “Shakespeare in Harlem,” “The Dream Keeper,” “Not Without Laughter,’ and “The Ways of White Folks” as well as the initial “The Weary Blues.”

“My writing,” Mr. Hughes said, “has been largely concerned with the depicting of Negro life in America.”

In one of his many anecdotes Mr. Hughes explained that he became a poet when he was named “class poet” in grammar school in Lincoln, Ill.

“I was a victim of a stereotype,” he observed wryly. “There were only two of us Negro kids in the whole class and our English teacher was always stressing the importance of rhythm in poetry.

“Well, everybody knows—except us—that all Negroes have rhythm, so they elected me class poet. I felt I couldn’t let my white classmates down, and I’ve been writing poetry ever since.”

James Langston Hughes, who dropped his first name, was born in Joplin, Mo., on Feb. 1, 1902. His mother was a schoolteacher and his father was a storekeeper.

After his graduation from Central High School in Cleveland, he went to Mexico and then attended Columbia University for a year. Mr. Hughes held a variety of jobs, including seaman on trips to Europe and Africa and busboy at the Washington hotel where he presented his poetry to Lindsay.

His first book, “The Weary Blues,” was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1925.

A scholarship enabled him to complete his education at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

His output was prodigious: poems, short stories, novels, librettos, lyrics, juveniles, pageants, anthologies, translations, television scripts. Between “The Weary Blues,” his first book of poems, and “The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers,” his last anthology, published in March, there were three dozen books.

His work lacked the power of the Negro writers who came after him. He felt as strongly as they did, but he was more amiable in expression. He was close to those he wrote about, and he captured their speech and their wry approach to life into his books.

No poetry of our day has caught the syncopated quality of jazz better than Mr. Hughes’s “Dream Boogie,” “Parade,” and “Warning: Augmented.” The plain speech of his verse and the ordinary subject matter often received as much criticism from Negroes as from those white people who couldn’t see his writing as poetry. The Negroes felt it lacked the proper dignity that was their due. They were right. What the poetry had instead was life—a quality that has kept it fresh and spirited over the years.

Mr. Hughes will be recognized for what he was: an American writer of charm and vitality.

Despite the variety of form, Mr. Hughes’s subject was nearly always the same: what it is like to be a black man in the United States. More gently than a younger generation of Negro writers would have preferred, Mr. Hughes always found the funny side of that life.

One of his most memorable characters, Jesse B. Semple, nicknamed Simple in the three books that Mr. Hughes wrote about him, spoke his mind with wry understatement.

“White folks,” Simple said, “is the cause of a lot of inconvenience in my life.”

Sometimes Mr. Hughes wrote about the adventures of Simple’s cousin, Minnie, who was in Harlem during the riots of 1964. “My advice to all womens taking in riots is to leave your wig at home,” said Minnie, who had lost hers.

This approach inevitably laid Mr. Hughes open to charges of clouding the bitter realities of racial strife with evasive humor.

He replied that he did not think the race problem was “too deep for comic relief.”

“Colored people are always laughing at some wry Jim Crow incident or absurd nuance of the color line,” he said. “If Negroes took all the white world’s boorishness to heart and wept over it as profoundly as our serious writers do, we would have been dead long ago.”

His defense was given more credence in light of the fact that Mr. Hughes’s humor did not disguise a compassion for his people and their oppressors, best expressed in the title of a collection of his short stories: “Laughing to Keep from Crying.”

Nor was Simple simply a clown. “Where do white folks get off calling everything bad black?” he once asked. “I would like to change all that around and say that the people who Jim Crow me have a white heart.”

Simple, who in 1957 became the hero of a Broadway musical, “Simply Heavenly,” may be Mr. Hughes’s most lasting contribution to literature. But it was as a poet that he first came to public attention.

His best work was stripped, laconic, set to an unheard blues beat. His interest in rhythm made him a follower of the poetry of Carl Sandburg and Vachel Lindsay in the 1920s.

“Weary Blues,” the poem Mr. Hughes showed Mr. Lindsay that fateful night at the Wardman Park Hotel, was full of the songs that Mr. Hughes had been hearing all his life—“gay songs, because you had to be gay or die; sad songs, because you couldn’t help being sad sometimes,” as he later said. “My best poems were all written when I felt the worst.”

Mr. Hughes was born on Feb. 1, 1902, in Joplin, Mo. His mother, Carrie, had been a grammar school teacher in Guthrie, Okla., when she met his father, James, a storekeeper. His parents separated shortly after his birth and he lived with his grandmother in Lawrence, Kan., until he was 12.

Mary Sampson Patterson Leary Langston was a tough, self-reliant woman whose first husband had been killed in John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and whose second husband had been active in the underground railway.

His father financed a year’s education for him at Columbia University. He found it a stale year, and decided to sign on as a freighter-hand and see the world.

The first freighter he could get was bound for Africa. “With that trip,” he said, “I began to live.” Impulsively, he threw all his books overboard and resolved to see things through his own eyes. Eventually he landed in Paris, where he lived for a year, supporting himself by washing dishes.

Mr. Hughes completed his formal education at Lincoln University, graduating in 1929.

The books that followed maintained his first success, particularly “Not Without Laughter,” a novel; “The Ways of White Folks,” short stories; “The Big Sea,” an autobiography; “Shakespeare in Harlem,” poems, and the Simple books: “Simple Speaks His Mind,” “Simple Takes a Wife” and “Simple Stakes a Claim.”

He also continued traveling, covering the Spanish Civil War for The Baltimore Afro-American, and visiting Cuba, Haiti, Africa, and the Soviet Union.

One of Mr. Hughes’s poems provided the title for Lorraine Hansberry’s play, “A Raisin in the Sun.”

What happens to a dream deferred

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

Like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

Like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

The theater tempted him, and he had considerable success in it. He wrote the lyrics for Kurt Weill’s “Street Scene,” a play called “Mulatto,” which had a successful run in New York though it was banned in Philadelphia because it dealt with miscegenation, and “Black Nativity.”

Mr. Hughes, who is survived by a brother, an uncle and an aunt, was charged during the McCarthy era with having belonged to several so-called Communist front organizations in the nineteen-thirties, a charge he did not deny, although he said he had never been a Communist.

Far from expressing dismay that some of his earlier books had been removed from United States Information Agency libraries around the world, Mr. Hughes told investigators that he was surprised they had been on the shelves in the first place.

NOËL COWARD

December 16, 1899–March 26, 1973

By Albin Krebs

Sir Noël Coward, whose light sharp wit enlivened the English stage for half a century as actor, playwright, songwriter, composer and director, died of a heart attack as he was preparing to have morning coffee yesterday in his villa, Blue Harbor, on the coast of Jamaica in the West Indies. He was 73 years old.

Hailed here and in London in the nineteen-twenties as a master of sophisticated, then-daring comedy, Sir Noël also sounded patriotic themes in “Cavalcade” between the wars and in “In Which We Serve,” a film about the Royal Navy in World War II. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1970.

“The world has treated me very well,” Sir Noël once said, adding, “but then I haven’t treated it so badly, either.”

The remark, typically free of self-effacement, constituted fair comment. In his 63 years as a theatrical jack-of-all-trades (and master of most), the urbane Sir Noël gave the world unstintingly of what he called “a talent to amuse.”

He wrote 27 comedies, dramas and musicals for the stage, the best-known of which were “Private Lives,” “Blithe Spirit,” “Cavalcade” and “Bitter-Sweet.”

Among the 281 songs for which he provided words and music—that he could not read notes did not deter him—were several that have become standards, including “Someday I’ll Find You,” “I’ll See You Again,” “Mad About the Boy” and “Mad Dogs and Englishmen.”

Of his films, the most memorable were the World War II epic of courage, “In Which We Serve,” and “Brief Encounter,” still considered one of the finest movies about romantic love.

In the last few years there has been an enormous revival of interest in the works of Sir Noël. Maggie Smith and Robert Stephens starred on the London stage in productions of “Design for Living” and “Private Lives.” Two revues culled from Sir Noël’s shows, songs and autobiographies are playing to capacity audiences.

The multitalented Sir Noël often acted in, directed and produced his own plays and films, and in the nineteen-fifties he turned to the new career of cabaret performer. By then, however, he had established himself as a major spokesman, in the dramatic arts, of an era—those two dazzling decades between two World Wars during which a generation of chic, smart-talking young people delighted in shocking their Victorian elders.

Because he often dealt with amoral characters who used mildly profane language and talked about sex, Sir Noël’s plays ran into censorship troubles. There were also objections to the fact that most of his stage characters were rich, spoiled, neurotic, vain, snobbish and selfish, but he made them bearable and even attractive by putting into their mouths an endless string of witticisms.

Some critics said there was too much humor, too much glittering, effervescent polish in his writing. “Private Lives” contained such lines as “Certain women should be struck regularly, like gongs,” which helped create the impression, for some, that the play was all sparkle and no fire.

On a deeper level, however, “Private Lives” and other Coward plays dealt with characters who almost continually said one thing while thinking another. The surface badinage was a cover. The relationships he repeatedly examined were those of people who couldn’t live together yet couldn’t live apart. In many ways, Sir Noël’s personal life and his personality resembled those of his characters. He was witty, generous, jaded, mercurial, sophisticated, lonely, snobbish.

In conversations, he sprinkled quips like salt. When asked whether he had ever tried to enlighten his audiences as well as amuse them, he replied: “I have a slight reforming urge, but I have rather cunningly kept it down.”

Sir Noël gave the appearance of being a great bon vivant, inhabiting a world of celebrity in which he enjoyed the friendship of such persons as Sir Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lynn Fontanne, George Bernard Shaw, Cary Grant and Marlene Dietrich.

Born Noël Pierce Coward on Dec. 16, 1899, in Teddington, near London, the future actor, singer, dancer, playwright, author, composer, librettist, lyricist and director was the son of Arthur Sabin Coward, an organist who was forced to work as a piano and organ salesman to support his family.

Sir Noël’s mother, the former Violet Agnes Veitch, was one of those doting stage mothers who relentlessly pushed their children forward in the theater. She remained the strongest influence in her son’s life until she died in 1954 at the age of 91.

Young Coward learned to play the piano by ear, but his formal education, which ended when he was 14, was haphazard. At 10 he made his professional debut on the London stage as Prince Mussel in an all-child production of “The Goldfish.” Soon he was bedeviling every producer in London for work.

“I was a brazen, odious little prodigy,” he said, “overpleased with myself and precocious to a degree. I was a talented boy, God knows, and when washed and smarmed down a bit, passably attractive.”

By 1914 he was touring as Slightly in “Peter Pan.” In 1918, when he was 19, he wrote his first play, “The Rat Trap,” which was not produced until 1926. Sir Noël developed a lifelong fondness for Americans during a stay of several months in New York in 1921. From then on he shuttled between London and New York, and came to regard the latter city as his second home.

His first stage success was “The Vortex,” which he wrote in 1923 and starred in the following year in London. The play was a melodrama and its central characters, a drug addict and his nymphomaniacal mother, shocked and titillated audiences.

At one point in 1925, three of London’s biggest stage successes were Coward hits. While he was still appearing in “The Vortex,” his revue “On with the Dance,” for which he wrote the book and songs, opened to raves, and his comedy of bad manners, “Hay Fever,” which he directed, was also successful. The same year marked the opening of his comedy “Fallen Angels.”

Success piled on top of success as Sir Noël’s plays were produced in New York, Paris and Berlin. In 1928 he turned out “This Year of Grace!,” a revue, and the next year the sentimental operetta “Bitter-Sweet,” which became an international hit. At the time he completed “Bitter-Sweet” he was appearing in “This Year of Grace!” in New York, and, he said, he composed the operetta’s best-known song, “I’ll See You Again,” while his taxi was caught in a traffic jam.

The pace at which he worked and lived took its toll. In 1930 he suffered a breakdown and took a long voyage to the Orient to recuperate. He could not resist the urge to work, however, and in four days, propped up in bed in his Shanghai hotel, he wrote “Private Lives,” the comedy that he had promised his friend, Gertrude Lawrence, to write for them to act in.

“‘Private Lives’ was described variously as ‘tenuous, thin, brittle, gossamer, iridescent and delightfully daring,’” Sir Noël said, “all of which connotated to the public mind cocktails, evening dress, repartee and irreverent allusions to copulation, thereby causing a gratifying number of respectable people to queue up at the box office.”

They did. “Private Lives” became the most popular and profitable Coward work. For himself and his friends the Lunts, Sir Noël wrote “Design for Living,” in which they appeared in New York in 1933. Meanwhile, “Cavalcade” had been staged in London and filmed in Hollywood. His 1933 musical, “Conversation Piece,” featured the songs “I’ll Follow My Secret Heart” and “Don’t Put Your Daughter on the Stage, Mrs. Worthington.” Later in the thirties he wrote and appeared with Miss Lawrence in “Tonight at 8:30,” a brace of short plays; “Present Laughter” and “This Happy Breed.” His biggest hit in World War II was “Blithe Spirit.”

“I behaved through most of the war with gallantry tinged, I suspect, by a strong urge to show off,” Sir Noël said. Actually, in addition to writing, producing, acting in and codirecting “In Which We Serve,” an important contribution to British morale, he drove himself to a physical breakdown by entertaining troops in Asia and Africa.

After the war, there was a pronounced shift in Sir Noël’s fortunes. The critics began to conclude that he and his work were outdated. In 1955 his bank overdraft was more than $60,000.

He fell back on two solutions to his problems: One was to take his cabaret act to the Desert Inn in Las Vegas, which paid him $40,000 a week to entertain what Sir Noël called “Nescafé Society.” The other was to escape high taxes in England by taking up residence in Jamaica and Switzerland.

The climate of the theater and the temper of the times had changed sufficiently by 1966 that Sir Noël was able to write and act in his most intensely autobiographical play, “A Song at Twilight.” The play concerns an aging homosexual writer who has not been able to write truthfully about himself in his work. Confronted by a blackmailer who upbraids him for having masked his homosexuality in his art and his life, the writer replies:

“Was that so unpardonable? I was young, ambitious and already almost a public figure. Was it so base of me to try to show to the world that I was capable of playing the game according to the rules?”

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

March 26, 1911–February 25, 1983

By Mel Gussow

Tennessee Williams, whose innovative drama and sense of lyricism were a major force in the postwar American theater, died yesterday at the age of 71. He was found dead in his suite in the Hotel Elysee on East 54th Street.

Officials said that death was due to natural causes.

The author of more than 24 full-length plays, including “The Glass Menagerie,” “A Streetcar Named Desire” and “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” the last two works winners of Pulitzer Prizes, Tennessee Williams was the most important American playwright after Eugene O’Neill.

He had a profound effect on the American theater and on American playwrights and actors, and he wrote with deep sympathy and expansive humor about society’s outcasts. Though his images were often violent, he was a poet of the human heart. His works, which are among the most popular plays of our time, continue to provide a rich reservoir of acting challenges. Among the actors celebrated in Williams roles were Laurette Taylor in “The Glass Menagerie,” Marlon Brando and Jessica Tandy in “A Streetcar Named Desire” (and Vivien Leigh in the movie version), and Burl Ives in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.”

“The Glass Menagerie,” his first success, was his “memory play.” Many of his other plays were his nightmares. His plays were almost all intensely personal, torn from his own private anguishes and anxieties.

He once described his sister’s room in the family home in St. Louis, with her collection of glass figures, as representing “all the softest emotions that belong to recollection of things past.” But, he remembered, outside the room was an alley in which, nightly, dogs destroyed cats.

Mr. Williams’s work, which was unequaled in passion and imagination by any of his contemporaries’ works, was a barrage of conflicts, of the blackest horrors offset by purity. Perhaps his greatest character, Blanche Du Bois, the heroine of “Streetcar,” has been described as a tigress and a moth. As Mr. Williams created her, there was no contradiction. His basic premise, he said, was “the need for understanding and tenderness and fortitude among individuals trapped by circumstance.”

Just as his work reflected his life, his life reflected his work. A monumental hypochondriac, he became obsessed with sickness, failure and death. Several times he thought he was losing his sight, and he had four operations for cataracts. Constantly he thought his heart would stop beating. In desperation, he drank and took pills immoderately.

He was a man of great shyness, but with friends he showed great openness, which often worked to his disadvantage. He was extremely vulnerable to demands—from directors, actresses, the public, his critics, admirers and detractors. Unfavorable reviews devastated him.

Success arrived suddenly in 1945, with the Broadway premiere of “The Glass Menagerie,” and it frightened him much more than failure.

He was born as Thomas Lanier Williams in Columbus, Miss., on March 26, 1911. His mother, the former Edwina Dakin, was the daughter of an Episcopal rector. His father, Cornelius Coffin Williams, was a traveling salesman who later settled down in St. Louis. There was an older daughter, Rose (memorialized as Laura in “the Glass Menagerie”), and in 1919 another son was born, Walter Dakin.

“It was just a wrong marriage,” the playwright wrote of his parents. His mother was the model for the foolish but indomitable Amanda Wingfield in “The Glass Menagerie,” his father for the brutish Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.”

While his father traveled, Tom was mostly brought up, and overprotected, by his mother, particularly after he contracted diphtheria at the age of five. By the time the family moved to St. Louis, the pattern was clear. Young Tom retreated into himself. He made up and told stories, many of them scary.

In the fall of 1929 he went off to the University of Missouri to study journalism, but soon dropped out and took a job as a clerk in a shoe company. It was, he recalled, “living death.”

To survive, every day after work he retreated to his room and wrote—stories, poems, plays—through the night. The strain led to a nervous breakdown. Sent to Memphis to recuperate, he joined a local theater group.

In 1937, Mr. Williams re-enrolled as a student, this time at the University of Iowa. There and in St. Louis he wrote an enormous number of plays, some of which were produced on campus. He graduated in 1938.

Success seemed paired with tragedy. His sister lost her mind. The family allowed a prefrontal lobotomy to be performed, and she spent much of her life in a sanitarium.

At 28, Thomas Williams left home for New Orleans. There he changed his style of living as well as his name, to become Tennessee Williams, and there he discovered new netherworlds, soaking up the milieu that would appear in “A Streetcar Named Desire.” He wrote stories, some of which later became plays, and entered a Group Theater playwriting contest. He won $100 and was solicited by the agent Audrey Wood, who became his friend and adviser.

“Battle of Angels,” a play he wrote during a visit to St. Louis, opened in Boston in 1940, closed in two weeks and did not come to New York. Mr. Williams, however, brought it back in a revised version in 1957 as “Orpheus Descending” and as the Marlon Brando–Anna Magnani movie, “The Fugitive Kind.”

To his amazement, Audrey Wood got him a job in Hollywood writing scripts for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer at $250 a week. Disdainfully, he began writing an original screenplay, which was rejected. Still under contract, he began turning the screenplay into a play titled “The Gentleman Caller,” which evolved into “The Glass Menagerie.” On March 31, 1945, five days after its author became 34, it opened on Broadway and changed Mr. Williams’s life and the American theater. He was inundated with success—the play won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle award—and he fought to keep afloat.

“Once you fully apprehend the vacuity of a life without struggle,” he wrote, “you are equipped with the basic means of salvation.” Realizing that his art was his salvation, he wrote his second masterpiece, “A Streetcar Named Desire.” Opening in 1947, “Streetcar” was an even bigger hit than “The Glass Menagerie.” It won Mr. Williams his second Drama Critics’ award and his first Pulitzer Prize.

For many years after “Streetcar,” almost every other season there was another Williams play on Broadway. Soon there was a continual flow from the stage to the screen. For more than 35 years, the stream was unabated. He produced an enormous body of work, including more than two dozen full-length plays, all of them produced, a record unequaled by any of his contemporaries. There were successes and failures, and often great disagreement over which was which. In 1948 there was “Summer and Smoke,” which failed on Broadway, was a huge success in a revival Off Broadway and made a star of Geraldine Page, one of many magnificent leading ladies in Mr. Williams’s works (others were Laurette Taylor, Jessica Tandy, Vivien Leigh, Maureen Stapleton, Anna Magnani). There followed “The Rose Tattoo,” “Camino Real,” “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (his second Pulitzer), “Orpheus Descending,” “Garden District” and “Sweet Bird of Youth.”

He also wrote two novels, the film “Baby Doll,” and his “Memoirs,” in which for the first time he wrote in detail about his homosexuality.

As he became increasingly successful, Mr. Williams became somewhat portly and seedy. Gradually he found it harder and harder to write. The turning point, as he saw it, was 1955, and after “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” there was a noticeable decline in his work. To keep going, he began relying on a combination of coffee, cigarettes, drugs and alcohol.

“The Night of the Iguana,” in 1961, was his last major success. After “Iguana,” Mr. Williams seemed to fall apart. But at the same time he discovered religion. In 1968 he was converted to Roman Catholicism, and his last plays, though still dealing with grotesques, also dealt with salvation.

“The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore,” which failed on Broadway and as an Elizabeth Taylor–Richard Burton movie entitled “Boom!,” was an allegory about a Christlike young man and a dying dowager.

In recent years, Mr. Williams, who is survived by his brother and his sister, divided his time between his apartment in New York and his house in Key West.

“I always felt like Tennessee and I were compatriots,” said Marlon Brando. “He told the truth as best he perceived it, and never turned away from things that beset or frightened him. We are all diminished by his death.”

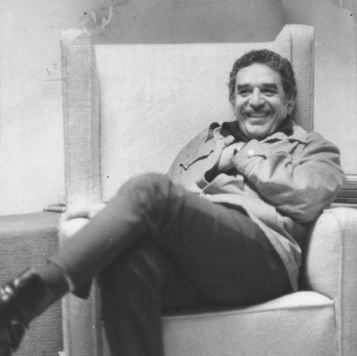

JORGE LUIS BORGES

August 24, 1899–June 14, 1986

By Edward A. Gargan

Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine short-story writer, poet and essayist who was considered one of Latin America’s greatest writers, died yesterday in Geneva, where he had been living for three months. He was 86 years old.

Mr. Borges died of liver cancer, said the executor of his estate, Osvaldo Luis Vidaurre.

While almost unknown outside Argentina before 1961, his stories, punctilious in their language and mysterious in their opaque paradoxes, attained a following that grew to international proportions. His writings explored the crannies of the human psyche, the fantastic within the apparently mundane, imaginary bestiaries and fables of obscure libraries and arcane scholarship. Many hailed him as the century’s most important Latin American writer.

Among his works of fiction that have appeared in the United States are “Ficciones,” “The Aleph and Other Stories” and “Labyrinths,” all published in 1962, and “A Universal History of Infamy,” in 1971. Among his collections of essays available in English are “The Book of Imaginary Beings” and “An Introduction to American Literature.” “Selected Poems, 1923–1967” was published in 1972 and “In Praise of Darkness,” consisting of poetry and short pieces, in 1974.

In 1975 John Updike wrote that Mr. Borges’s “driest paragraph is somehow compelling.”

“His fables are written from a height of intelligence less rare in philosophy and physics than in fiction,” he said. “Furthermore, he is, at least for anyone whose taste runs to puzzles or pure speculation, delightfully entertaining.”

For Mr. Borges, the short story was the most compelling form. “In the course of a lifetime devoted chiefly to books,” he wrote, “I have read but few novels and, in most cases, only a sense of duty has enabled me to find my way to their last page. I have always been a reader and rereader of short stories.”

Beginning in 1927, when he had a series of operations on his eyes, Mr. Borges was increasingly afflicted by blindness. While he called the condition a “slow, summer twilight,” it did not impede his work.

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires on Aug. 24, 1899. His father “was a philosophical anarchist,” Mr. Borges wrote, and a teacher of psychology. His mother translated American classics into Spanish.

At the age of six or seven, the young Borges began to write. “I was expected to be a writer,” he recalled later in life. He confessed that his first writing was modeled on classic Spanish writers, mostly [Miguel de] Cervantes.

In 1914 the family moved to Europe so that Jorge could attend school in Geneva. In the College of Geneva he was immersed in Latin, and outside it he tackled German, eventually finding his way to [Arthur] Schopenhauer.

“Were I to choose a single philosopher, I would choose him,” Mr. Borges wrote. “If the riddle of the universe can be stated in words, I think these words would be in his writings.”

After Mr. Borges received his degree, his family moved to Spain, where his first poem, “Hymn to the Sea,” was published. In 1921, he returned with his family to Buenos Aires, where he continued to write.

The “real beginning” of his career, Mr. Borges wrote, came in the early 1930’s with a series of sketches called “A Universal History of Infamy.” In these, which “were in the nature of hoaxes and pseudo-essays,” Mr. Borges chronicled the lives of Lazarus Morell, who both freed and imprisoned slaves; of Tom Castro, an implausible prodigal son; of the widow Ching, a pirate who terrorized the seas of Asia; of Monk Eastman, a New York gunman and “purveyor of iniquities”; of Kotsuke no Suke, who refused to commit hara-kiri, “which as a nobleman was his duty.”

With Mr. Borges’s next story, “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim,” written in 1935, the shape of many of his later stories was established. The story is a fictive review of a book purportedly published in Bombay. Mr. Borges invests the mythical volume with a genuine publisher and reviewer but, as he wrote later, “the author and the book are entirely my own invention.”

In this story, many of the basic literary elements that came to characterize Mr. Borges’s style were apparent: a concern for history and identity; the central role of an obscure scholarly work; a maze of discourse laden with elaborate and Byzantine detail; footnotes; meticulous references to remote academic journals, and deliberately translucent paradox.

Mr. Borges took his first full-time job in 1937 as an assistant in a branch of the Buenos Aires Municipal Library; he remained there for nine years, completing his work each day in an hour and devoting the rest of his time to reading and writing. In this period, he wrote the short story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” which he described as a “halfway house between the essay and true tale.”