P. T. BARNUM

July 4, 1810–April 7, 1891

BRIDGEPORT, Conn.—At 6:22 o’clock tonight the long sickness of P. T. Barnum came to an end by his quietly passing away at Marina, his residence in this city.

Shortly after midnight there came an alarming change for the worse. Drs. Hubbard and Godfrey, who were in attendance, saw at once that the change was such as to indicate that the patient could not long survive.

Among the sorrowing group in the sick room were Mrs. Barnum, the Rev. L. B. Fisher, pastor of the Universalist church of this city, of which Mr. Barnum was a member; Mrs. D. W. Thompson, Mr. Barnum’s daughter; Mrs. W. H. Buchtelle of New York, another daughter; C. Barnum Seeley, his grandson; Drs. Hubbard and Godfrey, his physicians; and W. D. Roberts, his faithful colored valet. The scene at the deathbed was deeply pathetic. All were in tears.

Throughout the city tonight there is the deepest sorrow. Day before yesterday Mr. Barnum was 80 years and nine months of age.

For more than 40 years, the great American showman toiled to amuse the public, and his life was filled with many remarkable adventures.

Phineas Taylor Barnum was born in Bethel, Connecticut, on July 5, 1810. His father, Philo Barnum, was a tailor, a farmer, and a tavern keeper.

The boy was early taught that if he would succeed in the world he must work hard. When he was only six years of age he drove cows to and from pasture, weeded the kitchen garden at the back of the humble house in which he was born, and as he grew older rode the plow horse, and whenever he had an opportunity attended school.

In arithmetic he was particularly apt, and he was also at a remarkably early age aware of the value of money. When he was six he had saved coppers enough to exchange for a silver dollar. This he “turned” as rapidly as he could, and by peddling homemade molasses candy, gingerbread, and a liquor made by himself called cherry rum, he had accumulated when he was not quite 12 a sum sufficient to buy a sheep and a calf.

For years the life of young Barnum was one of constant struggle. His father died when he was 15, and he was left almost penniless. He was by turns a peddler and trader, a clerk in Brooklyn and New York, the keeper of a small porter house, the proprietor of a village store, and editor of a country newspaper. After this he kept a boarding house, made a trip to Philadelphia and was married to a young tailoress, whom he years after described as “the best woman in the world.”

Then in 1835, he found the calling for which he seems to have been born. In short, he went into “the show business.”

Regarding this period in his life he later wrote: “By this time it was clear to my mind that my proper position in this busy world was not yet reached. I had not found that I was to cater for that insatiate want of human nature—the love of amusement; that I was to make a sensation in two continents, and that fame and fortune awaited me so soon as I should appear in the character of a showman. The show business has all phases and grades of dignity, from the exhibition of a monkey to the exposition of that highest art in music or the drama which secures for the gifted artists a worldwide fame Princes well might envy. Men, women, and children who cannot live on gravity alone need something to satisfy their gayer, lighter moods and hours, and he who ministers to this want is, in my opinion, in a business established by the Creator of our nature.”

The first venture to which Mr. Barnum thus refers was a remarkable negro woman, who was said to have been 161 years old and a nurse of Gen. George Washington. The wonders of this person are set forth in this notice, from the Pennsylvania Inquirer of July 15, 1835:

“CURIOSITY.—The citizens of Philadelphia and its vicinity have an opportunity of witnessing at Masonic Hall one of the greatest natural curiosities ever witnessed, viz., Joice Heth, a negress, aged 161 years, who formerly belonged to the father of Gen. Washington. She has been a member of the Baptist Church 116 years, and can rehearse many hymns and sing them according to former custom. She was born near the old Potomac River, in Virginia, and has for 90 or 100 years lived in Paris, Ky., with the Bowling family.”

For $1,000, Mr. Barnum bought the “wonderful negress,” and, making money by the venture, he continued to follow the business of a showman. During the years which followed he traveled all over this country and in many other parts of the world.

Of all his enterprises, however, he regarded his connection with the American Museum and his management of Jenny Lind and Tom Thumb as the most important. On the 27th of December, 1841, he obtained control of the American Museum, on the corner of Ann Street and Broadway in New York, and for years afterward he continued to conduct that establishment.

It became one of the most famous places of amusement in the world. In it were exhibited “the Feejee Mermaid,” “the original bearded woman,” and giants and dwarfs almost without end.

It was in November, 1842, that Mr. Barnum engaged Charles S. Stratton, whom he christened Tom Thumb. With him he traveled and made large sums of money in different parts of the world.

Regarding a visit which he made with Tom Thumb to the Queen of England, Mr. Barnum wrote: “We were conducted through a long corridor to a broad flight of marble steps, which led to the Queen’s magnificent picture gallery… The General familiarly informed the Queen that her pictures were ‘first-rate.’”

Mr. Barnum regarded his engagement of Jenny Lind as one of the great events in his career. That engagement was entered into in 1850. It resulted in a fortune for Mr. Barnum, and in the payment to Jenny Lind for 95 concerts of the sum of $176,675.09.

After his engagement with Jenny Lind, Mr. Barnum was everywhere regarded as being “a made man.” But, as the years went on, trouble fell upon him, and by unwise speculation he lost every penny he had in the world.

Still he did not give up the fight, but by the help of friends, the increase in value of certain real estate owned by him, and the great energy which was one of his chief traits, he again commenced in a small way, subsequently took Tom Thumb to Europe for a second visit, and repaired his broken fortunes. Later on he again undertook the management of the museum in New York, and upon its destruction by fire established “the new museum” further up Broadway. It was also burned, and he lost much money. But fortune again smiled upon him, and as a manager of monster circuses and traveling shows he met with much success in all parts of the country.

During all his life Mr. Barnum was a great believer in the power of advertising. No man knew better than he the value of printer’s ink, and nothing was too ambitious for him to undertake.

One of the greatest chances of his life came with Jumbo. He had often gazed on that monster in the Zoological Gardens at London, but it had never occurred to him as possible to possess the English pet. One of his agents induced the manager of the garden to offer the animal for $2,000. Mr. Barnum snapped up the offer at once. There was a cry of protest from all England. Pictures of Jumbo, Jumbo stories and poetry, Jumbo collars, neckties, cigars, fans, polkas, and hats were put on the market and worn, sung, smoked, and danced by the entire English nation.

Mr. Barnum was importuned to name the price at which he would relinquish his contract and permit Jumbo to remain in London. He said he had promised to show the animal in America and had advertised him extensively. Therefore, $100,000 would not induce him to cancel the purchase.

When Jumbo and his movements became a matter of deep public interest, the newspapers printed all they could get about him. His untimely death was mourned by two nations.

Mr. Barnum published his will in 1883. He valued his share in the show at $3,500,000, and the Children’s Aid Society was named as a beneficiary of a certain percentage of each season’s profits. “To me there is no picture so beautiful as smiling, bright-eyed, happy children; no music so sweet as their clear and ringing laughter,” the great showman explained. “That I have had power to provide innocent amusement for the little ones, to create such pictures, to evoke such music, is my proudest reflection.”

EDWIN BOOTH

November 13, 1833–June 7, 1893

Edwin Booth, the well-known actor, died at the Players’ this morning at 1:17 o’clock. For several days he had been growing weaker, and all hope of his recovery had been abandoned.

It was in a heavy, painless sleep that Mr. Booth’s spirit passed away.

Mrs. Grossman, Mr. Booth’s daughter, had maintained a silent vigil, and it was in her arms that her father died.

Within half an hour every club in New York knew of the great tragedian’s death.

His father, Junius Brutus Booth, came to America in 1821, discouraged with the treatment he received in the English theater. There is no doubt that this Booth was a great actor, greater in many parts than his rival, Edmund Kean. But no place in the public heart could be found for another Kean while Kean lived.

Junius Brutus Booth’s second wife, had been Mary Ann Holmes of Reading, England. They had 10 children. Of these John Wilkes took to the stage, but, because of his profligacy, such gifts as he had were wasted.

The elder Booth bought a farm near the town of Belair, near Baltimore, Md., and there Edwin was born, Nov. 13, 1833.

He was, almost from his infancy, his father’s favorite. But the father did not want his favorite son to be an actor. He never dreamed that little Edwin, in whom he saw no traces of talent, would be for years the foremost actor of a Nation of 60 million, and in his time the wisest and most eloquent interpreter of Shakespeare on the English-speaking stage.

Edwin Booth made his first appearance on the stage Sept. 10, 1849, at the Boston Museum, in the insignificant part of Tressel in “Richard III.” He made his first appearance in New York Sept. 27, 1850, at the old National Theatre, in “The Iron Chest,” acting Wilford to his father’s Mortimer.

Edwin Booth and his father went to California in June, 1852, and appeared in several plays at the American Theatre in Sacramento. The father died later that year.

Edwin Booth became a member of the stock company of the Sacramento Theatre in 1855. He played Richard III on Aug. 11, and was hailed as “a promising young actor.” The next week, he appeared as Hamlet for the first time.

He was hailed as the rising star, upon whose shoulders the mantle of the elder Booth had fallen. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who was then a Lieutenant, told in an after-dinner speech nearly 35 years later at Delmonico’s, as he stood beside the chair of Mr. Booth, how, when he could not afford to go to the theater, he used to sit at night on the veranda of his hotel across the way and listen to the thunders of applause that greeted the young tragedian.

Mr. Booth’s first New York engagement was at Burton’s New Theatre. It began May 4, 1857. The young tragedian appeared as Richard III, King Lear, Hamlet, and Romeo. These engagements were not profitable, but the tide had turned in his favor Nov. 26, 1860, when he began another engagement at the same house, which had been renamed Winter Garden Theatre.

His Hamlet began to be spoken of seriously. The popular applause indicated that his Hamlet was already preferred to all other Hamlets.

Mr. Booth went to England for the first time in 1861 and acted in London. He was married that year to Mary Devlin, who had been an actress. She died on Feb. 21, 1863, when she was not yet 23, leaving an infant daughter, Edwina.

At Winter Garden Theatre Sept. 29, 1862, Mr. Booth reappeared and was cordially received. “Hamlet” and “The Merchant of Venice” drew large audiences. Mr. Booth’s next engagement at Winter Garden Theatre began with “Hamlet” May 3, 1864. This theater was then leased by him and his brother-in-law, John Sleeper Clarke.

The manager, William Stuart, an energetic Irish adventurer, was a skillful advertiser, and spared no pains in trumpeting the merits of Edwin Booth. The posters on the fences bearing his name were big enough for a circus.

Public excitement about the actor was at fever heat. Critics who doubted “if the modern stage had anything to equal his Hamlet” were plentiful. The handsome face of the actor, shaded by dark flowing locks and bearing an expression of poetic melancholy, was impressed on the eye of the multitude. His beautiful voice was raved about. His hour of triumph was at hand.

The celebrated long run of “Hamlet”—100 nights—began at Winter Garden, Oct. 31, 1864. His “Hamlet” was transferred to the Boston Theatre on March 24, 1865.

Three weeks later the country received the dreadful shock caused by the assassination of President Lincoln by Edwin Booth’s younger brother. Edwin suffered no indignity, but the shame of the family disgrace burdened his mind. He never afterward appeared in Washington.

He returned to the New York stage at Winter Garden Theatre, Jan. 3, 1866, as Hamlet. He was received with cheers which expressed the sympathy of the public and the confidence in his patriotism, but perhaps also indicated the delight of the crowd at the sight of the man who had inevitably become more conspicuous since his brother’s dastardly crime.

Booth had now reached his zenith. He had never before acted with the firmness, repose, strength, and exquisite delicacy that then marked his work, and he never surpassed the portrayals of Shakespeare’s heroes which he gave during that last year at Winter Garden Theatre. In December, 1866, he played Iago to the Othello of Bogumil Dawison, the renowned German actor. Each used his own native language, and this was the first of many similar performances on the New York stage.

The Hamlet Medal, testifying to public approbation of Booth’s impersonation of the Prince of Denmark, was presented to him at Winter Garden, Jan. 22, 1867, after a performance of Shakespeare’s most esteemed tragedy. The medal, now preserved among the treasures of The Players in their clubhouse in Gramercy Park, is of gold, oval in shape, surrounded by a golden serpent. In the center is the head of Booth as Hamlet.

Mr. Booth was now, in his 34th year, the most popular actor in the United States. An enormous fortune seemed to be within his grasp. He had long desired to own a theater in which Shakespeare should be fittingly represented.

The cornerstone of Booth’s Theatre, at Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street, was laid April 8, 1868, and the house was opened to the public Feb. 3, 1869. The exterior was of stone, massive and imposing in appearance. The auditorium was spacious and handsome. The acoustics were perfect. There was a great crowd in the theater on opening night for “Romeo and Juliet.”

“Romeo and Juliet” ran until April 12, when “Othello” was produced with equal magnificence, Mr. Booth playing the Moor to the Iago of Adams, and the young actress Mary McVicker playing Desdemona. She and Mr. Booth were married on June 2, 1869.

Mr. Booth came forward again on Jan. 5, 1870, in “Hamlet.” Booth’s Hamlet, as graceful, touching, and picturesque as ever, was then supported, none too well, by the Claudius of Theodore Hamilton, the Laertes of William E. Sheridan, and the Polonius of D. C. Anderson.

But the money went out faster than it came in. Booth had mortgaged the property heavily, and borrowed large sums to meet his expenses. His advisers and assistants were neither wise nor competent. The stage was neglected, and the plays badly mounted. After the performance June 21, 1873, Booth formally retired from the management.

In February, 1874, Mr. Booth filed a petition in voluntary bankruptcy. His assets were announced as $9,000; the liabilities were enormous. Jarrett & Palmer, the firm of theatrical speculators who had inflicted Boucicault’s “Formosa, or the Railroad to Ruin,” on New York at Niblo’s, secured the lease of the theater at an annual rental of $40,000. Mr. Booth protested against their use of his name as a trademark, but they found another Booth, the owner of a printing house, who cheerfully lent his name to the theater, which was called Booth’s to the end. The property was sold, in foreclosure, Dec. 3, 1874.

The theater passed through many vicissitudes. Clara Morris tried to act Lady Macbeth there and failed. Sarah Bernhardt there made her American début.

The ill-fated theater, the noblest home the drama ever had in New York, was sold in 1883 to the notorious James D. Fish and Ferdinand Ward, who rebuilt it for mercantile purposes.

In March, 1891, at the Broadway Theatre, Booth played Shylock to the Bassanio of Mr. Barrett. Although his acting had been listless in his later years, he had never before offered a performance so feeble. His speech was halting; he could not always he heard; he walked with difficulty. He had been ill, and he lacked the strength to continue his labors. The sudden death of Lawrence Barrett, March 20, 1891, caused an early close of the season.

Booth then appeared in Brooklyn, at the Academy of Music. The representation of “Hamlet” there Saturday afternoon, April 4, 1891, was generally regarded as his “farewell,” and such, indeed, it proved to be.

The club known as The Players, designed to provide a social meeting place for actors, dramatists, managers, and persons interested in the welfare of the stage, and to get together a great theatrical library and preserve valuable dramatic mementos and works of art, was founded in 1888 by Edwin Booth and others. Mr. Booth bought the house at 16 Gramercy Park and paid for its redecoration under the direction of Stanford White. This he presented to The Players. He retained the use of rooms in the house, which he made his home. The clubhouse was opened to the members and their friends on Dec. 31, 1888.

In recognition of this splendid gift a supper was given at Delmonico’s in Mr. Booth’s honor, March 30, 1889. The following Wednesday Mr. Booth was seized with an alarming fainting fit on stage in Rochester, N.Y., during a performance of “Othello.” His physicians said at the time of his last engagement in New York that he was afflicted with malaria, caused by the bad ventilation and imperfect plumbing of some of the theaters in which he had been acting.

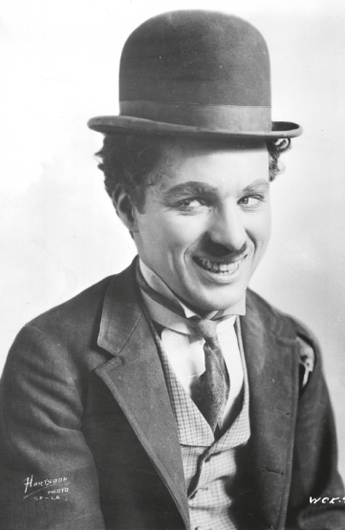

SARAH BERNHARDT

October 22 or 23, 1844–March 26, 1923

PARIS—Sarah Bernhardt is dead. The “greatest actress” passed away at 7:59 P.M. in the arms of her son, Maurice. Death came in her home with windows open on the Boulevard Pereire. It was the sudden closing of these windows that gave the signal to those waiting and watching without that Bernhardt was dead.

Bernhardt’s grandson, M. Grosse, brought the first flowers into the death chamber—mauve and white lilacs. Flowers came from many friends, and soon the room was heaped with them, those from the family and dearest friends being placed on the bed.

The actress’s son, her granddaughter, Lysiane, and Mlle. Louise Abbema, who was Bernhardt’s best friend, had remained close to the chamber where the patient lay.

Bernhardt suffered greatly in her last illness. From time to time she became delirious and declaimed passages from the tragedy “Phèdre” and “L’Aiglon,” her two greatest triumphs.

Word of Bernhardt’s death spread through Paris rapidly. At the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, where “L’Aiglon” was playing, the announcement was made in the middle of the first act. The play was stopped and the audience filed out sorrowfully.

Crowds collected outside the residence on the Boulevard Pereire, gazing at the shuttered windows and watching the carriages and automobiles bringing celebrities of the literary and dramatic world.

Mme. Bernhardt was 78 years old. An acute uremic condition was the cause of death.

“I dream of dying, like the great Irving, in the harness,” said Mme. Bernhardt in September, 1910. That sentence sums up her whole life. Work was her fountain of youth. She was never idle; she never rested.

Sarah Bernhardt was the natural child of Julie Bernhardt and a merchant of Amsterdam, who died shortly after her birth, on Oct. 22, 1844. At the age of eight she was placed in Mme. Fressard’s school at Auteuil, and two years later, in 1855, was a scholar at the Grandchamps Convent at Versailles. The religious atmosphere of the convent made a strong appeal to her emotional nature, and after being converted to the Catholic faith she decided to become a nun.

Here also she appeared in her first play, called “Toby Recovering His Eyesight.” This was a miracle play, and Mme. Bernhardt appeared, as she wrote in her “Memoirs,” in “heavenly blue tarletan, with a blue sash around my waist to help confine the filmy drapery, and two paper wings fastened upon each shoulder for celestial atmosphere.”

Her mother was much alarmed when her daughter announced that she would become a nun, and a family council was called. She was taken to the theater every night, but she persisted in her wish to enter the nunnery. When 14 years old, she was taken to a performance of “Britannicus” at the Théâtre Français, and was so moved and impressed that her family decided to make her an actress.

Two years later she competed for the National Conservatoire, and at the public trials recited a simple fable of La Fontaine’s, “The Two Pigeons.” Her performance so astonished that she was immediately and unanimously entered.

In 1862 Edmond Thierry called her to the Comédie Francaise, and she made her professional début in a minor part on “Iphigenie.” Then came four years of hard work done in obscurity.

She entered the Gymnase de Montigny in 1866. Duquesnel of the Odéon recognized her latent genius and engaged her, paying her first year’s salary out of his own pocket.

In 1867 Mme. Bernhardt made her debut as Armande in “Les Femmes Savantes.” This appearance is considered the real starting point of her career, and she began to be famous by the end of 1869.

Then came the Franco-Prussian war, and she became a nurse. She turned a Parisian theater into a hospital and for more than a year gave herself up to the care of the wounded and dying.

In 1872 Mme. Bernhardt signed a contract to become a life member of the Comédie Francaise and scored great successes in “Phèdre,” as Berthe in “La Fille de Roland,” and as Posthumia in “Rome Vaincue.” Three years later she was elected a sharing life member of the Comédie Française.

Then came a period of clashes with M. Perrin, the managing director of the Comédie Française. Mme. Bernhardt received roles that were uncongenial. One day, after remonstrating with M. Perrin for assigning her the part of Clorinda in “L’Aventurière,” she burst out of his office like a tempest and gave up the stage.

She returned to the Comédie Française, only to break with M. Perrin permanently shortly after. This last break was brought about by an incident typical of the Bernhardt temperament.

She insisted on going up in a balloon—this was during the Exposition of 1878—and M. Perrin was sure she would break her engagement to play at the matinée that day. She landed just in time to keep the appointment, but Perrin was furious and announced that she was fined 1,000 francs.

Mme. Bernhardt immediately resigned. She then played for the first time outside France, appearing in London in “Phèdre” and as Mrs. Clarkson in “L’Etrangère.”

“The English people,” she said after this invasion, “first among all foreign nations welcomed me with such kindness that they made me believe in myself.”

On Nov. 8, 1880, she made her first appearance in New York at Booth’s Theatre. Mme. Bernhardt’s first American tour comprised 27 performances in this city and 136 in 39 other cities during a period of seven months. She played eight dramas, including “La Dame aux Camelias” and “Frou Frou.”

Then came a tour of Russia and Denmark, and in 1882 she earned fresh triumphs at the Vaudeville in Paris. One year later she became the owner of the Porte Sainte-Martin Theatre and played in repertoire until 1886, when she made her second American tour. Her third American tour followed in 1888–1889.

Then in 1891–1893 Mme. Bernhardt made an extended tour covering the United States, South America and many capitals of Europe. On her return to Paris she undertook the management of the Theatre de la Renaissance.

Mme. Bernhardt made her fifth American tour in 1896, and that December was present at a festival given in her honor in Paris. She was crowned queen of the drama before 500 artists, actors and authors.

Her sixth American tour was made in 1901–1902, during which she gave 180 performances in the principal cities. Mme. Bernhardt returned to her playhouse in Paris and presented a number of new plays with brilliant success, and in 1905 made her seventh visit to this country under the management of the Shuberts.

She played in both North and South America, and in Quebec, Canada, she went through, an unpleasant experience. She was credited by the newspapers with making certain criticisms of French Canadians, and she and her company were attacked by a mob on their way to the station after the engagement. Eggs, stones, sticks and snowballs were thrown.

She played in halls, armories, skating rinks, and churches, and in Texas, owing to the fact that no theaters could he obtained, she played in a Barnum & Bailey tent.

In 1910 she returned to this country for the first of her “farewell tours.” In 35 weeks she gave 285 performances.

Mme. Bernhardt returned to this country again in December, 1912. Her repertoire consisted of famous scenes from her great successes, and the tour was an unqualified success. When the war came, she converted her theater into a hospital, just as she had nearly a half-century before.

Then in the midst of her ministrations she was stricken with inflammation of the right knee and had to undergo an operation which cost her her right leg. The operation was performed in February, 1915. That she was acting again at the end of six months was typical of her indomitable will.

In November she returned to the Paris stage and acted in a dramatic sketch called “Les Cathedrales,” in which the players represented the voices of the devastated cathedrals of France. Mme. Bernhardt was the voice of the Cathedral of Strasbourg, and when she recited the closing words, “Weep, Germans, weep: thy Prussian Eagles have fallen bleeding into the Rhine,” the audience became wild with emotion.

Mme. Bernhardt arrived on her last visit here in October, 1916. She then set off on one of the most arduous tours of her career, playing first in legitimate theaters and then on the Keith vaudeville circuit. At the Palace in this city she invariably received an ovation, particularly for her performance as the young French officer in “Du Theatre au Champ d’Honneur.” She closed her season in Cleveland in October, 1918.

In October, 1921, she presented at her own theater “La Gloire,” a play written for her by Maurice Rostand. Admitted to be the greatest actress of all time, Mme. Bernhardt also won distinction as a sculptor, writer, and artist. Her group “After the Storm” received honorable mention at the Salon in 1878. Her book “Dans les Nuages,” written in 1878, describing her balloon ascension, was widely read, as were her “Memoirs.”

She was married in 1882 to Jacques Damala, a handsome Greek actor of her own company, but they parted after one year. Later, when he was dying of consumption, she removed him to her home and nursed him until the end.

For 40 years Mme. Bernhardt’s residence in Paris was the old house on the Boulevard Pereire. Her natural son lived with her there.

Her best work was done where she was able to display her powerful emotions. She was never surpassed and never will be, her critics say, in the emotional school. She played more than 200 parts and created most of them.

She received honors without number. Public fêtes for her were given in London and Paris and other capitals, and in Vienna one night after playing “Hamlet” the audience tore the horses from her carriage and dragged her through the street shouting “Vive Bernhardt!”—Associated Press

HARRY HOUDINI

March 24, 1874–October 31, 1926

DETROIT—Harry Houdini, world famous as a magician, a defier of locks and sealed chests and an exposer of spiritualist frauds, died here this afternoon after a week’s struggle for life.

Death was due to peritonitis, which followed an operation for appendicitis. A second operation was performed last Friday. Like a newly discovered serum, used for the first time in Houdini’s case, it was of no avail. He was 52 years old.

The chapter of accidents that ended fatally for the man who so often had seemed to be cheating the jaws of death began early in October at Albany, N.Y. On the opening night of his engagement a piece of apparatus used in his “water torture cell” trick struck him on the foot.

A bone was found to be fractured and Houdini was advised to discontinue his tour. He declined.

On Tuesday, Oct. 19, while in Montreal he addressed a class of students on spiritualistic tricks. After the address he commented on the ability of his stomach muscles to withstand hard blows without injury.

One of the students without warning struck him twice over his appendix. After he had boarded a train for Detroit he complained of pain.

Upon his arrival, Dr. Leo Kretzka, a physician, told the patient there were symptoms of appendicitis. At his hotel after the performance the pain increased. The following afternoon he underwent an operation for appendicitis.

According to the physicians, one of the blows he received in Montreal caused the appendix to burst.

Whatever the methods by which Harry Houdini deceived a large part of the world for nearly four decades, his career stamped him as one of the greatest showmen of modern times. With few exceptions, he invented all his tricks and illusions. In one or two cases Houdini alone knew the whole secret.

Houdini was born on March 24, 1874. His name originally was Eric Weiss and he was the son of a rabbi. He did not take the name Harry Houdini until he had been a performer for many years.

Legend has it that he opened his first lock when he wanted a piece of pie in the kitchen closet. When scarcely more than a baby he showed skill as an acrobat and contortionist, and both these talents helped his start in the show business and his development as an “escape king.”

At the age of nine Houdini joined a traveling circus, touring Wisconsin as a contortionist and trapeze performer. Standing in the middle of the ring, he would invite anyone to tie him with ropes and then free himself inside the cabinet.

In the ring at Coffeyville, Kan., a sheriff tied him and then produced a pair of handcuffs with the taunt, “If I put these on you, you’ll never get loose.”

Houdini, still only a boy, told him to go ahead. After a much longer stay in the cabinet than usual, the performer emerged, carrying the handcuffs in his hands.

That was the beginning of his long series of escapes from every known sort of manacle. For years he called himself the Handcuff King.

From 1885 to 1900 he played all over the United States, in museums, music halls, circuses, and medicine shows.

During a six-year tour of the Continent he escaped from dozens of famous prisons. He returned to America to find his fame greatly increased and a newly organized vaudeville ready to pay him many times his old salary.

In 1908 Houdini dropped the handcuff tricks for more dangerous and dramatic escapes, including one from an airtight vessel, filled with water and locked in an iron-bound chest. He would free himself from the so-called torture cell, his own invention. In this he was suspended, head down, in a tank of water. He would hang from the roof of a skyscraper, bound in a straitjacket, from which he would wriggle free to the applause of the crowd in the street below. Thrown from a boat or bridge into a river, bound hand and foot and locked and nailed in a box, doomed to certain death by drowning or suffocation, he would emerge in a minute or so, swimming vigorously to safety.

An evidence of the deep impression his work made on the public mind is the fact that the Standard Dictionary now contains a verb, “houdinize,” meaning “to release or extricate oneself (from confinement, bonds, or the like), as by wriggling out.”

Houdini, who lived at 278 West 113th Street and in 1894 married Wilhelmina Rahner of Brooklyn, for 33 years tried to solve the mysteries of spiritism. He told friends he was ready to believe because he would find joy in proof that he could communicate with his parents and friends who had passed on. He had agreed with friends and acquaintances that the first to die was to try to communicate from the spirit world to the world of reality. Fourteen of those friends had died, but none had ever given a sign, he said.

“Such an agreement I made with both my parents,” Houdini said. “They died and I have not heard from them. I thought once I saw my mother in a vision, but I now believe it was imagination.”

Houdini counted that he had had “four close-ups with death” in his career of more than 30 years as a mystifier. The closest was in California, where he risked his life on a bet. Seven years ago in Los Angeles he made a wager that he could free himself from a six-foot grave into which he was to be buried after being manacled.

“The knowledge that I was six feet under the sod gave me the first thrill of horror I had ever experienced,” Houdini was wont to say. “The momentary scare, the irretrievable mistake of all daredevils, nearly cost me my life, for it caused me to waste a fraction of breath when every fraction was needed to pull through. I had kept the sand loose about my body so that I could work dexterously. I did. But as I clawed and kneed the earth my strength began to fail. Then I made another mistake. I yelled. Or, at least, I attempted to, and the last remnants of my self-possession left me. Then instinct stepped in to the rescue. With my last reserve strength I fought through, more sand than air entering my nostrils. The sunlight came like a blinding blessing, and my friends about the grave said that, chalky pale and wild-eyed as I was, I presented a perfect imitation of a dead man rising.

“The next time I am buried it will not be alive if I can help it.”

D. W. GRIFFITH

January 22, 1875–July 23, 1948

By Seymour Stern

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—David Wark Griffith, one of the first and greatest contributors to the motion picture art, died this morning in Temple Hospital after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. His age was 73.

The producer of “The Birth of a Nation,” and pioneer in such techniques as closeups, fade-outs and flashbacks, was stricken at the Hollywood Knickerbocker Hotel, where he lived. Mr. Griffith, who is survived by a brother, was divorced from his second wife, the former Evelyn Marjorie Baldwin.

Mr. Griffith had been inactive in recent years. But the name of D. W. Griffith, the master producer and director of silent motion pictures, is synonymous with “father of the film art” and “king of directors.”

He produced and directed almost 500 pictures costing $23,000,000 and grossing $80,000,000. His most famous film, “The Birth of a Nation,” has grossed more than $48,000,000.

Although Mr. Griffith did not originate all the technical devices credited to him, he originated many of them, and vastly improved others. Chief among his improvements was his development of the closeup, first used in 1895, into a dramatic psychological contribution that shaped the entire art of the cinema.

Among the multitude of advanced methods which he started were the long shot, the vista, the vignette, the iris or eye-opener effect, the cameo-profile, the fade-in and fade-out, soft focus, back lighting, tinting, rapid-cutting, parallel action, mist photography, high and low angle shots, night photography, and the moving camera.

He was the first director to depart from the standard 1,000-foot film. This caused a break between him and the old Biograph Company. He then made the first four-reeler. “Judith of Bethulia,” which had instantaneous success. When Mr. Griffith ordered a close-up shot of a human face, his cameraman, Billy Bitzer, quit in disgust. At the first close-up there were hisses and cries of “Where are their feet?”

It was as a creator of significant content in the films themselves, however, that Mr. Griffith was a mighty force in the cinema. Even before “The Birth of a Nation,” that epic of the Civil War and the Reconstruction Period, which, directed by a man whose family had been ruined by the fall of the Confederacy, was deeply biased but was filled with great sweep and movement, he had exercised his bold conception of the exalted purpose which the medium might serve.

Long before the names of Sergei Eisenstein, Fritz Lang, Alfred Hitchcock, and Frank Capra were heard of, Mr. Griffith brought to the screen important historical and philosophical themes, challenging social questions, visionary prophecies. His films were emotional, dramatic, intellectual and esthetic.

In 1916 his “Intolerance” appeared, with four parallel stories, a stupendous re-creation of the Ancient World and an apocalyptic image-prophecy of the Second Coming of Christ. In this film, Griffith used 16,000 “extras” in a single scene.

Mr. Griffith brought lyric poetry and high tragedy to the screen in 1919 in “Broken Blossoms,” a passionate plea for a renewal of the Christian ideal in interracial relations. His “Way Down East,” a folk-melodrama of New England in the Nineties, produced in 1920, used landscapes and natural backgrounds as vital psychological and dramatic elements of a story.

In “Orphans of the Storm,” in 1922, Mr. Griffith combined magnificent spectacle with a social theme, using the French Revolution as a platform from which to attack communism and Soviet Russia.

In 1924, Mr. Griffith produced the mammoth “America,” another great historical pageant, this time of the American Revolution.

His last important film, in 1925, was “Isn’t Life Wonderful,” a grim tale of Polish refugees in post–World War I Germany.

In the days of his greatest glory Mr. Griffith never used a shooting script. “Intolerance,” although it was 22 months in production and consumed 125 miles of film, was photographed entirely from his “mental notes.”

Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish were outstanding examples of his genius in choosing and training performers for the new art. He induced Douglas Fairbanks to leave the stage for the screen. Dorothy Gish, Mabel Normand, Lionel Barrymore, and the Talmadge sisters owed their film careers to him.

Born at La Grange, Ky., on Jan. 22, 1875, the son of Colonel Jacob Wark Griffith and Margaret Oglesby Griffith, David Wark Griffith started work at 16 on a local newspaper.

After seeing Julia Marlowe in “Romola,” he decided to become an actor. After working in various stock companies, he won entry to moving pictures as an actor, working at the Edison studio and then at Biograph.

In July, 1908, he made his first film, “The Adventures of Dollie.”

In 1919, with Pickford, Fairbanks and Charles Chaplin, he formed United Artists Corporation, under whose seal some of the screen’s outstanding productions were released.

Is Griffith merely the remarkable director who in 23 years of filmmaking employed upwards of 75,000 persons; who discovered, trained and launched so many directors and “stars” that to list them is to compile a “Who’s Who in Hollywood, Today and Yesterday”? Is he merely an inventor of cinematic devices and technical devices?

The central fact in the director’s story is the monumental, single-handed fight Griffith waged for freedom of expression in a medium cursed with censorship and control. He was the one creative figure who fought alone against financial monopoly and cultural dictatorship.

His most important masterpieces, “The Birth of a Nation” and “Intolerance,” were financed, produced and exhibited in entire independence of the Hollywood film industry, which refused backing for both films. Three other major works—“Way Down East,” “Orphans of the Storm” and “America”—were financed and produced independently of the industry.

The last three films were produced not in Hollywood but at Mamaroneck, N.Y. Griffith stuck his flag at Mamaroneck in 1924, after he had made the small but powerful film “Isn’t Life Wonderful.”

Although he made films for eight more years, practically none of his later output reflects the greatness and originality of mind that conceived Belshazzar’s feast in “Intolerance,” the imagination that fashioned the ride of the Clansmen in “The Birth of a Nation,” or the cinematic wizardry that flashcut Paul Revere’s ride in “America.”

JAMES DEAN

February 8, 1931–September 30, 1955

PASO ROBLES, Calif.—James Dean, 24-year-old motion picture actor, was killed tonight in an automobile accident near here.

A spokesman for Warner Brothers, for whom Mr. Dean had just completed “The Giant,” said he had no details of the accident except that the actor was en route to a sports car meeting at Salinas. He was driving a small German speedster.

Mr. Dean was the star of Elia Kazan’s film “East of Eden,” released last April and taken from John Steinbeck’s novel. It was his first starring role in films.

He also appeared in “Rebel Without a Cause,” still unreleased.

In 1954 he attracted [the] attention of critics as the young Arab servant in the Broadway production of “The Immoralist.” His portrayal won for him the Donaldson and Perry awards.

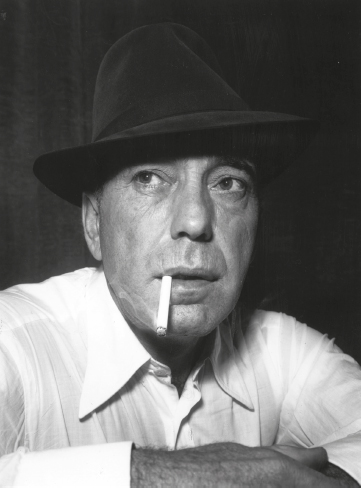

HUMPHREY BOGART

December 25, 1899–January 14, 1957

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—Humphrey Bogart died in his sleep this morning in his Holmby Hills home. The 57-year-old movie actor, an Academy Award winner, had been suffering for more than two years from cancer of the esophagus.

Mr. Bogart leaves his wife, Lauren Bacall, the actress, whom he married in 1945, and who was his fourth wife. Mr. Bogart is also survived by a son, a daughter, and a sister.

Mr. Bogart was one of the most paradoxical screen personalities in the recent annals of Hollywood. He often deflated the publicity balloons that keep many a screen star aloft, but he remained one of Hollywood’s top box-office attractions for more than two decades.

On screen he was most often the snarling, laconic gangster who let his gun do his talking. In private life, however, he could speak wittily on a wide range of subjects and make better copy off the cuff than the publicists could devise for him.

Mr. Bogart received an Academy Award in 1952 for his performance in “The African Queen.” Still, he made it clear that he set little store by such fanfare. Earlier he had established a mock award for the best performance in a film by an animal, making sure that the bit of satire received full notice in the press.

But despite this show of frivolity, he was fiercely proud of his profession. “I am a professional,” he said. “I have a respect for my profession. I worked hard at it.”

Attesting to this are a number of highly interesting characterizations in such films as “The Petrified Forest” (1936), “High Sierra” (1941), “Casablanca” (1942), “To Have and Have Not” (1944), “Key Largo” (1948), “The Treasure of Sierra Madre” (1948), “The African Queen” (1951), “Sabrina,” (1954), “The Caine Mutiny” (1954) and “The Desperate Hours” (1955). The actor’s last film, “The Harder They Fall,” was released last year.

Mr. Bogart’s sense of responsibility toward his profession may have stemmed from the fact that both his parents were successful professionals. His mother was Maud Humphrey, a noted illustrator and artist. His father was Belmont DeForest Bogart, a surgeon. Their son, born on Christmas Day in 1899, was reared in fashionable New York society.

Mr. Bogart worked for a time with World Films and then as a stage manager for an acting group. It was an easy step to his first roles in the early 1920’s. His rise to fame over the next 15 years, however, was a hard road, often lined with critical brickbats.

He appeared in “Swifty” and plugged on in drawing-room comedies, appearing in “Hell’s Bells, “The Cradle Snatchers,” “It’s a Wise Child” and many others in which he usually played a callow juvenile or a romantic second lead.

He accepted a contract with Fox in 1931, but roles in a few Westerns failed to improve matters, and soon he was back on Broadway, convinced that his hard-bitten face disqualified him for close-ups as a matinee idol.

But toward the end of 1934 he used his granite-like face to rebuild, with enormous success, a new dramatic career. Having heard that Robert E. Sherwood’s “The Petrified Forest” had a gangster role, he approached Mr. Sherwood for the part.

Mr. Bogart was asked to return in three days for a reading. When he reappeared he had a three-day growth of beard and was wearing shabby clothes. His reading and appearance brought him the supporting role of Duke Mantee, his most memorable Broadway role. Mr. Bogart later performed the same role for the movie to considerable critical acclaim.

This was the first of more than 50 pictures that Mr. Bogart made. A spate of crime dramas followed, including “Angels with Dirty Faces.” “The Roaring Twenties,” Bullets or Ballots,” “Dead End,” “San Quentin” and, finally, “High Sierra” in 1941.

Mr. Bogart then insisted on roles with more scope. They were forthcoming in such films as “Casablanca,” “To Have and Have Not” and “Key Largo,” wherein Mr. Bogart’s notorious screen hardness was offset by a latent idealism that showed itself in the end.

In “The Treasure of Sierra Madre,” as a prospector driven to evil by a lust for gold, the range of his characterization won him new followers.

A further range of his talents was displayed in “The African Queen,” wherein his portrayal of a tramp with a yen for gin and Katharine Hepburn won him an “Oscar.” Another distinguished portrait was that of the neurotic Captain Queeg in the movie version of “The Caine Mutiny.” His aptitude for romantic comedy became clear when he played the bitter businessman who softens under the charms of Audrey Hepburn in “Sabrina.” Mr. Bogart also appeared in “The Barefoot Contessa,” made in 1954.

The movie actor made no secret of his nightclubbing. He was also a yachting enthusiast. At one point in his career he reportedly made $200,000 a film, and he was for years among the top 10 box-office attractions.

CECIL B. DE MILLE

August 12, 1881–January 21, 1959

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—Cecil B. De Mille died of a heart ailment today in his home on De Mille Drive here. He was 77 years old.

At his bedside when he died were a daughter, Cecilia, and her husband, Joseph Harper. Mrs. De Mille, who is 85 and has been ailing for several years, was not informed until later in the morning. They had been married for 56 years.

Although confined to his home since last Saturday, Mr. De Mille was preparing to start filming “On My Honor,” a history of the Boy Scout movement and its founder, the late Lord Baden-Powell.

Cecil Blount De Mille was the Phineas T. Barnum of the movies—a showman extraordinary.

A pioneer in the industry, he used the broad medium of the screen to interpret in “colossal” and “stupendous” spectacles the story of the Bible, the splendor that was Egypt, the glory that was Rome. He dreamed in terms of millions, marble pillars, golden bathtubs and mass drama; spent enormous sums to produce the rich effects for which he became famous.

He produced more than 70 major films, noted for their weight and mass rather than for subtlety or finely shaded artistry.

In 1953 he won his first Academy Award, for “The Greatest Show on Earth.” Since then he had been showered with honors. France named him a Knight of the Legion of Honor, the Netherlands inducted him into the Order of Orange Nassau, and Thailand conferred on him the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant.

The fact that his first Oscar did not come until 40 years after he had produced one of the earliest four-reel feature films, “The Squaw Man,” was brushed off with a characteristic De Millean gesture:

“I win my awards at the box office.”

This was true. His pageants and colossals awed the urban, suburban and backwoods audiences. By 1946 his personal fortune, despite his regal spending habits, was estimated at $8,000,000.

The producer basked in publicity’s intense glare in 1944–45 when he made a heroic issue of a demand by the union of which he was a member that he pay a $1 contribution to its political action fund. He had been in radio about a decade by that time, staging shows for a soap company at a reported salary of $5,000 a week.

Mr. De Mille carried the fight to the courts, was defeated, and then went on a one-man campaign against political assessments by unions. He later sought reinstatement in the union but failed to get it.

Mr. De Mille was born at De Mille Corners, a backwoods crossroads in Ashfield, Mass., on Aug. 12, 1881, while his parents were touring New England with a stock company. His father, Henry Churchill De Mille, was of French-Dutch ancestry; his mother, the former Matilda Beatrice Samuel, of English stock.

At 17 he went on the stage. In the cast of one play, “Hearts Are Trumps,” was Constance Adams, daughter of a New Jersey judge. They were married in 1902.

In 1908 Mr. De Mille threw in his lot with the ambitious Jesse Lasky and with a newcomer in the theater, Sam Goldwyn. All three reached the top rung in the movie world, though along separate paths.

The first product of their movie company was “The Squaw Man.” It was turned out in an abandoned stable in Los Angeles with crude equipment, but it bore Mr. De Mille’s mark.

He was credited with many motion picture innovations. Indoor lighting was first tried out on an actor in “The Squaw Man.” This picture, besides being the screen’s first epic, was also the first to publicize the names of its stars.

On his first day as head of the Lasky-Goldwyn-De Mille combine, Mr. De Mille signed three unknowns—a $5 cowpoke named Hal Roach, an oil-field hand named Bill (Hopalong Cassidy) Boyd and a thin-nosed teenager who called herself Gloria Swanson. This was the nucleus around which he built his galaxy of screen stars.

To Mr. De Mille was attributed the inspiration for doing different versions of a popular picture. The so-called “sneak preview”—showing a film to a test audience—was another contribution.

The first “Ten Commandments,” produced in 1923 at a cost of $1,400,000, made money. From that time on Mr. De Mille wallowed in extravagant props and super-gorgeous sets.

A second version, issued in 1956 and differing greatly from the first, grossed a reported $60,000,000 here and abroad.

Mr. De Mille, who gave the University of Southern California a theater in memory of his parents, was lavish with gifts to other institutions.

In June, 1958, he learned that plans to place translations of the hieroglyphics on the Egyptian obelisk in Central Park were being put aside for lack of funds. He offered to pay the cost of erecting four bronze plaques at the base of “Cleopatra’s Needle,” saying:

“As a boy, I used to look upon the hieroglyphics as so many wonderful pictures.”

Two weeks ago, the Department of Parks announced that Mr. De Mille had donated $3,760 for the project.

CLARK GABLE

February 1, 1901–November 16, 1960

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—Clark Gable, for 30 years “King” of Hollywood actors, died tonight of a heart ailment. He was 59 years old.

—The Associated Press

Mr. Gable was one of the world’s most popular actors. For many years he was among the 10 top box-office attractions. Theater marquees would announce simply, “This week: Clark Gable.”

To millions the tall, handsome man with the mustache, broad shoulders, brown hair and gray eyes was the symbol of masculinity, “naughty but nice.”

He did not think he was a great actor. “I can’t emote worth a damn,” he said. And when he was earning $7,500 a week, he hung in his dressing room reminders of the days when he was a struggling actor or piling lumber in Oregon for $3.20 a day. Across the mementos he wrote: “Just to remind you, Gable.”

There were many Gable legends. One was that in “It Happened One Night” (1934) he had sabotaged the undershirt industry overnight by peeling off his shirt in the picture and revealing nothing underneath.

“I didn’t know what I was doing to the undershirt people,” he recalled, adding, “I hadn’t worn an undershirt since I started to school.”

Early in his career he was turned down by one top studio. He quoted an executive as saying: “Gable won’t do. Look at his big ears.” The executive later hired him.

William Clark Gable (he dropped his first name after he entered the theater) was born in Cadiz, Ohio, on Feb. 1, 1901. His father was an oil contractor. His mother died before he was one year old.

At 15, after his father had remarried, the family moved to Ravenna, Ohio. His father quit oil drilling for farming. Young Gable forked hay, fed hogs and wanted to be a physician. But when he saw his first play, he decided to be an actor, and he got a job with a troupe that played everything from “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to “Her False Step.”

When the company closed in Montana, he took a freight train to Oregon, where he worked in a lumber company, sold neckties, and was a telephone company linesman.

In 1924 Mr. Gable joined a theater company in Portland. He made his first appearance on the screen in a silent film starring Pola Negri. He appeared in two Los Angeles stage productions and then headed for Broadway.

In three years, he portrayed mostly villains. Then he returned to Los Angeles, where he was a hit in the role of Killer Mears in “The Last Mile.”

This led to a movie role in “The Painted Desert” in 1930. The story is that Mr. Gable was interviewed and asked if he could ride a horse. He said he could, got the job, then went out and learned how to ride.

His effort won him a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. He first became a leading man in “Dance, Fools, Dance,” with Joan Crawford. His first big hit was “A Free Soul,” in which he slapped Norma Shearer.

Women by the thousands wrote in that they, too, would like to be slapped by Mr. Gable. “For two years I pulled guns on people or hit women in the face,” he later recalled.

His pictures included “Hell Divers,” “Susan Lennox,” “Polly of the Circus” “Strange Interlude,” “Red Dust,” “No Man of Her Own,” “The White Sister,” “Hold Your Man,” “Night Flight,” and “Dancing Lady.” His roster of leading ladies included Greta Garbo, Jean Harlow, Carole Lombard and Helen Hayes.

In 1934, he was loaned to Columbia Pictures, which starred him in a comedy, “It Happened One Night.” Claudette Colbert played a runaway heiress and Mr. Gable a newspaperman, traveling by bus from Miami to New York. Both won Academy Awards for the best performances of the year.

The next year he played Fletcher Christian in “Mutiny on the Bounty,” which won an Academy Award as the best film of the year.

In the next seven years Mr. Gable appeared in more than 25 films, including “China Seas,” “San Francisco,” “Saratoga,” “Test Pilot,” “Idiot’s Delight,” “Gone with the Wind,” “Boom Town,” “They Met in Bombay” and “Somewhere I’ll Find You.”

From 1932 through 1943, he was listed among the first 10 money-making stars in the yearly surveys by The Motion Picture Herald. After time out for military duty, he regained that ranking in 1947, 1948, 1949 and 1955.

Observers believe that his films have grossed more than $100,000,000, including $50,000,000 for “Gone with the Wind.” He had roles in at least 60 pictures.

After his third wife, Miss Lombard, was killed in a plane crash during a bond tour in World War II in 1942, Mr. Gable enlisted in the Army Air Forces as a private. He was then 41. He rose to major, took part in bomber missions over Europe, filmed a combat movie and won the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After the war, he returned to Hollywood, and a Metro slogan, “Gable is back and Garson’s got him” spread across the country. He starred with Greer Garson in “Adventure.” Then followed such films as “The Hucksters,” “Mogambo,” “The King and Four Queens,” “The Tall Men,” “Soldier of Fortune,” “Teacher’s Pet,” “Run Silent, Run Deep,” and “But Not for Me.”

“It Started in Naples,” a comedy with Mr. Gable and Sophia Loren, opened in New York in September, 1960. In July, 1960, Mr. Gable had begun work with Marilyn Monroe on “The Misfits.”

Mr. Gable married five times. His fifth wife was Mrs. Kay Williams Spreckels, a former model and actress, whom he married in 1955. Last Sept. 30, Mr. Gable announced that she was to have a child in the spring, making Mr. Gable a father for the first time.

GARY COOPER

May 7, 1901–May 13, 1961

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—Gary Cooper died today of cancer at his home in the Holmby Hills section of Los Angeles. He was 60 years old last Sunday.

The tall, lean actor, whose cowboy roles had made him a world symbol of the courageous, laconic pioneer of the American West, had been critically ill for several weeks.

The seriousness of his illness was revealed on April 17 when the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences was bestowing its Oscars on artists and technicians. A special statuette was ready for Mr. Cooper for his contributions during his long career. He had previously won two Oscars for acting—in the title role of “Sergeant York” in 1941 and as the courageous sheriff in “High Noon” in 1953.

However, James Stewart, the actor, accepted the honor for his close friend and gave a short, emotional tribute. Reporters, who had accepted the explanation that Mr. Cooper was unable to attend the ceremony because of a pinched nerve in his back, later learned that he was critically ill with cancer.

To millions of Americans, Gary Cooper represented the All-American Man.

He was an American frontier hero in “The Plainsman,” an O.S.S. hero in “Cloak and Dagger,” a Naval hero in “Task Force,” a homespun millionaire hero in “Mr. Deeds Goes to Town,” a common-man political hero in “Meet John Doe,” a baseball hero in “The Pride of the Yankees,” a medical hero in “The Story of Dr. Wassell” and a national hero in “Sergeant York.”

He was the strong, silent man not only of the great outdoors, where he was one of its slowest-talking and fastest-drawing citizens, but also of powerful dramas and sophisticated comedies.

“Ungainly, ungrammatical, head-scratching, ineloquent men draw comfort and renewed assurance from Gary Cooper,” a writer once said.

Long, lean and broad of shoulder, Mr. Cooper walked gingerly, off screen as well as on. His eyes were of chilly blue. He was handy with a shotgun or rifle.

One writer said that in only two major respects did Mr. Cooper differ markedly from his screen self: he didn’t go around wearing a horse and he didn’t say “They went that-a-way.” Mr. Cooper reportedly would say, “Thet way.”

The men who directed his pictures said he had an instinctive sense of timing, a quick intelligence, the wit to think a role through and get to the heart of a character.

“I recognize my limitations,” he once said. “For instance, I never tried Shakespeare.” He paused and grinned slowly. “That’s because I’d look funny in tights.”

Mr. Cooper was once asked to give the reasons for his success. He replied: “I don’t really know but maybe it’s because once in a while I find a good picture, the happy combination of director and actors, which gives me a fresh start. Mostly I think it’s because I look like the guy down the street.”

Mr. Cooper was born May 7, 1901, in Helena, Mont., and christened Frank James Cooper. His father, Charles Henry Cooper, was a British lawyer who had gone to Helena, married a Montana girl, managed a ranch while practicing law and became a justice of the Montana Supreme Court.

The family went to England when young Cooper was nine and returned to Montana four years later. He worked on the family ranch.

“Getting up at 5 o’clock in the dead of winter to feed 450 head of cattle and shoveling manure at 40 below ain’t romantic,” he once recalled.

After two years at Grinnell College in Iowa, he headed for Los Angeles in 1924. His first job there was door-to-door solicitation for a photography studio. One day he met two friends from Helena who told him the Fox Western Studios were looking for riders. He got a job—at $10 a day.

Then he heard that Tom Mix, the cowboy star, was making $15,000 a week. Mr. Cooper decided to devote a year to make good in the movies.

A friend from Indiana suggested that he change his name because there already were several Frank Coopers in pictures, and Gary was a city whose name always sounded poetic to her.

Mr. Cooper got several bit parts, and just before the year ran out, got his first big role, opposite Vilma Banky in the 1926 film “The Winning of Barbara Worth.” Eventually he equaled, if not surpassed, Tom Mix’s $15,000 a week, although he was generally paid by the picture—reportedly around $300,000 in recent years.

In April, 1960, he underwent prostate-gland surgery in Boston. A major intestinal operation was performed five weeks later in Hollywood.

After his recovery, the actor went to England to make his last film, “The Naked Edge,” in which he portrayed a murderer opposite Deborah Kerr.

In 1933, Mr. Cooper married the socially prominent Veronica Balfe, who had a brief screen career as Sandra Shaw. The couple had one daughter, Maria.

In 1959, Mr. Cooper became a member of the Roman Catholic Church, of which his wife and daughter already were members.

Also surviving Mr. Cooper is his 85-year-old mother, Mrs. Alice Bracia Cooper of Los Angeles.

MARILYN MONROE

June 1, 1926–August 5, 1962

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—Marilyn Monroe, one of the most famous stars in Hollywood’s history, was found dead early today in the bedroom of her home in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles. She was 36 years old.

Beside the bed was an empty bottle that had contained sleeping pills. Fourteen other bottles of medicines and tablets were on the nightstand.

The impact of Miss Monroe’s death was international. Her fame was greater than her contributions as an actress. Her marriages to and divorces from Joe DiMaggio, the former Yankee baseball star, and Arthur Miller, the Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, were accepted by millions as the prerogatives of this contemporary Venus.

The events leading to her death were in tragic contrast to the comic talent and zest for life that had helped to make “The Seven Year Itch” and “Some Like It Hot” smash hits. Other of her notable films included “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” “Bus Stop” and “How to Marry a Millionaire.”

During the last few years Miss Monroe had suffered severe setbacks. Her last two films, “Let’s Make Love” and “The Misfits,” were box-office disappointments. After completion of “The Misfits,” written by Mr. Miller, she was divorced from him.

The last person to see her alive was her housekeeper, Mrs. Eunice Murray, who had lived with her. Mrs. Murray told the police that Miss Monroe retired to her bedroom about 8 P.M. yesterday.

About 3:25 A.M. today, the housekeeper noticed a light under Miss Monroe’s door. She called to the actress but received no answer. She tried the bedroom door, but it was locked.

The housekeeper telephoned Miss Monroe’s psychoanalyst, Dr. Ralph R. Greenson. When he arrived at her two-bedroom bungalow, he broke a pane of the French window and opened it. Determining that the star was dead, he phoned Miss Monroe’s physician. After his arrival, the police were called.

In the last two years Miss Monroe had become the subject of considerable controversy in Hollywood. Some persons gibed at her aspirations as a serious actress and considered it ridiculous that she should have gone to New York to study under Lee Strasberg. Miss Monroe’s defenders, however, asserted that her talents had been underestimated by those who thought her appeal to audiences was solely sexual.

The life of Marilyn Monroe, the golden girl of the movies, ended as it began, in misery and tragedy. Her death closed an incredibly glamorous career and capped a series of somber events that began with her birth as an unwanted, illegitimate baby and was illuminated during the last dozen years by the lightning of fame.

The first man to see her on the screen, the man who made her screen test, felt the almost universal reaction as he ran the wordless scene, in which she walked, sat down and lit a cigarette.

“I got a cold chill,” he said. “This girl had something I hadn’t seen since silent pictures. This is the first girl who looked like one of those lush stars of the silent era. Every frame of the test radiated sex.”

Billy Wilder, the director, called it “flesh impact,” adding, “Flesh impact is rare. Three I remember who had it were Clara Bow, Jean Harlow and Rita Hayworth. Such girls have flesh which photographs like flesh. You feel you can reach out and touch it.”

Fans paid $200,000,000 to see her project this quality. No sex symbol of the era other than Brigitte Bardot could match her popularity. Toward the end, she also convinced critics and the public that she could act.

During the years of her greatest success, she saw two of her marriages end in divorce. She suffered at least two miscarriages. Her emotional insecurity deepened, and her many illnesses came upon her more frequently.

In 1961, she was twice admitted to hospitals in New York for psychiatric observation and rest. On June 8 she was dismissed by Twentieth Century Fox after being absent all but five days during seven weeks of shooting “Something’s Got to Give,” in which she starred.

“It’s something that Marilyn no longer can control,” one of her studio chiefs confided. “Sure she’s sick. She believes she’s sick. She may even have a fever, but it’s a sickness of the mind.”

In her last interview, published in the Aug. 3 issue of Life magazine, she said: “I was never used to being happy, so that wasn’t something I ever took for granted.”

Miss Monroe was born in Los Angeles on June 1, 1926. The name on the birth record is Norma Jean Mortenson, the surname of the man who fathered her, then abandoned her mother. She later took her mother’s last name, Baker.

Both her maternal grandparents and her mother were committed to mental institutions. Her uncle killed himself. Her father died in a motorcycle accident three years after her birth.

During her mother’s stays in asylums, she was farmed out to 12 sets of foster parents. One family gave her empty whisky bottles to play with instead of dolls. She also spent two years in a Los Angeles orphanage.

Her dream since childhood had been to be a movie star, and the conviction of her mother’s best friend was borne out; day after day she had told the child: “You’re going to be a beautiful girl when you get big. You’re going to be a movie star. Oh, I feel it in my bones.”

Miss Monroe’s dimensions—37-23-37—were voluptuous but not extraordinary. She had soft blonde hair and wide, dreamy gray-blue eyes. She spoke in a baby voice that was little more than a breathless whisper.

Fans wrote her 5,000 letters a week, at least a dozen of them proposing marriage. Her second husband, Mr. DiMaggio, and her third, Mr. Miller, were American male idols.

She was 16 when she married for the first time. The bridegroom was James Dougherty, an aircraft worker. They were divorced four years later, in 1946. Her two subsequent divorces came in 1954, when she split with Mr. DiMaggio after only nine months, and in 1960, after a four-year marriage to Mr. Miller.

Miss Monroe became famous with her first featured role of any prominence, in “The Asphalt Jungle,” in 1950. Her appearance was brief but unforgettable. From the instant she moved onto the screen with that extraordinary walk of hers, people asked themselves, “Who’s that blonde?”

In 1952 it was revealed that Miss Monroe had been the subject of a nude calendar photograph that was shot while she was an unsuccessful starlet. The news created a scandal, but it was her reaction to the scandal that was remembered. She told interviewers that she had needed the money to pay her rent.

She also revealed her sense of humor. When asked by a woman journalist, “You mean you didn’t have anything on?” she replied breathlessly: “Oh, yes, I had the radio on.”

One of Miss Monroe’s most exasperating quirks was her tardiness. During the years of her fame, she was up to 24 hours late for appointments.

“True, she’s not punctual,” said Jerry Wald, head of her studio, “but I’m not sad about it. I can get a dozen beautiful blondes who will show up promptly in makeup at 4 A.M. each morning, but they are not Marilyn Monroe.”

Speaking of her career and her fame, Miss Monroe once said wistfully: “It might be kind of a relief to be finished. It’s sort of like I don’t know what kind of a yard dash you’re running, but then you’re at the finish line and you sort of sigh—you’ve made it! But you never have—you have to start all over again.”

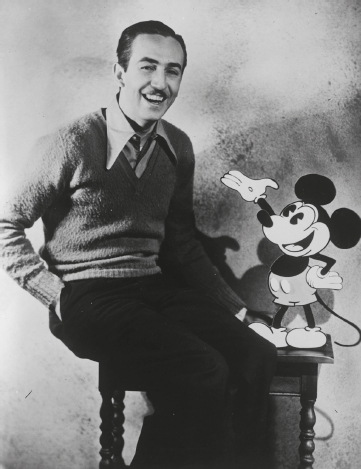

WALT DISNEY

December 5, 1901–December 15, 1966

LOS ANGELES—Walt Disney, who built his whimsical cartoon world of Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs into a $100-million-a-year entertainment empire, died in St. Joseph’s Hospital here this morning. He was 65 years old.

He had undergone surgery for the removal of a lung tumor that was discovered after he entered the hospital for treatment of an old neck injury received in a polo match.

Just before his last illness, Mr. Disney was supervising the construction of a new Disneyland in Florida, a ski resort in Sequoia National Forest and the renovation of the 10-year-old Disneyland at Anaheim. His motion-picture studio was turning out six new productions and several television shows.

Although Mr. Disney held no formal title at Walt Disney Productions, he was in direct charge. Indeed, with the recent decision of Jack L. Warner to sell his interest in the Warner Brothers studio, Mr. Disney was the last of Hollywood’s veteran moviemakers who remained in personal control of a major studio.

He is survived by his wife, Lillian, two daughters and his brother Roy, who is president and chairman of Walt Disney Productions.

From his fertile imagination and industrious factory of drawing boards, Walt Elias Disney fashioned the most popular movie stars ever to come from Hollywood and created one of the most fantastic entertainment empires in history.

In return for the happiness he supplied, the world lavished wealth and tributes upon him. He was probably the only man in Hollywood to have been praised by both the American Legion and the Soviet Union.

Where any other Hollywood producer would have been happy to get one Academy Award, Mr. Disney smashed all records by accumulating 29 Oscars.

“We’re selling corn,” Mr. Disney once told a reporter, “and I like corn.”

Mr. Disney went from seven-minute animated cartoons to become the first man to mix animation with live action, and he pioneered in making feature-length cartoons. His nature films were almost as popular as his cartoons, and eventually he expanded into feature-length movies using only live actors.

From a small garage-studio, the Disney enterprise grew into one of the most modern movie studios in the world, with four sound stages on 51 acres. Mr. Disney acquired a 420-acre ranch that was used for shooting exterior shots for his movies and television productions. Among the lucrative by-products of his output were many comic scripts and enormous royalties paid to him by toy-makers.

Mr. Disney’s restless mind created one of the nation’s greatest tourist attractions, Disneyland, a 300-acre tract of amusement rides, fantasy spectacles and re-created Americana that cost $50.1 million.

By last year, when Disneyland observed its 10th birthday, it had been visited by some 50 million people. Its international fame was emphasized in 1959 by the then Soviet Premier, Nikita S. Khrushchev, who protested that he had been unable to see Disneyland. Security arrangements could not be made in time.

Even after Disneyland had proven itself, Mr. Disney declined to consider suggestions to leave well enough alone: “Disneyland will never be completed as long as there is imagination left in the world.”

Repeatedly, as Mr. Disney came up with new ideas, he encountered skepticism. For Mickey Mouse, the foundation of his realm, Mr. Disney had to pawn and sell almost everything because most exhibitors looked upon it as just another cartoon. But when the public had a chance to speak, the noble-hearted mouse with the high-pitched voice, red pants, yellow shoes and white gloves became the most beloved of Hollywood stars.

When Mr. Disney decided to make the first feature-length cartoon, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” Hollywood experts scoffed that no audience would sit through such a long animation. It became one of the biggest money-makers in movie history.

Mr. Disney was thought a fool when he became the first important movie producer to make films for television. His detractors, once again, were proven wrong.

He was, however, the only major movie producer who refused to release his movies to television. He contended, with a good deal of profitable evidence, that each seven years there would be another generation that would flock to the movie theaters to see his old films.

Mickey Mouse would have been fame enough for most men, but not for Walt Disney. He created Donald Duck, Pluto and Goofy. He dug into books for Dumbo, Bambi, Peter Pan, The Three Little Pigs, Ferdinand the Bull, Cinderella, the Sleeping Beauty, Brer Rabbit, Pinocchio. In “Fantasia,” he blended cartoon stories with classical music.

Though Mr. Disney’s cartoon characters differed markedly, they were all alike in two respects: they were lovable and unsophisticated. Most popular were big-eared Mickey of the piping voice; choleric Donald Duck of the unintelligible quacking; Pluto, that most amiable of clumsy dogs, and the seven dwarfs, who stole the show from Snow White: Dopey, Grumpy, Bashful, Sneezy, Happy, Sleepy and Doc.

Mr. Disney seemed to have had an almost superstitious fear of considering his movies as art, though an exhibition of some of his leading cartoon characters was once held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “I’ve never called this art,” he said. “It’s show business.”

From Harvard and Yale, this stocky, industrious man who had never graduated from high school received honorary degrees. By the end of his career, the list of 700 awards and honors that Mr. Disney received from many nations filled 29 typewritten pages, and included 29 Oscars, four Emmys and the Presidential Freedom Medal.

Toys in the shape of Disney characters sold by the many millions. One of the most astounding exhibitions of popular devotion came in the wake of Mr. Disney’s films about Davy Crockett. In a matter of months, youngsters all over the country who would balk at wearing a hat in winter were adorned in ’coonskin caps in midsummer.

In some ways Mr. Disney resembled the movie pioneers of a generation before him. Like them, he insisted on absolute authority and was savage in rebuking a subordinate. An associate of many years said the boss “could make you feel one-inch tall, but he wouldn’t let anybody else do it. That was his privilege.”

He was not afraid of risk. One day, when all the world thought of him as a fabulous success, he told an acquaintance, “I’m in great shape; I now owe the bank only eight million.”

Mr. Disney had no trouble borrowing money in his later years. Bankers, in fact, sought him out. Last year Walt Disney Productions grossed $110 million. His family owns 38 percent of this publicly held corporation, and all of Retlaw, a company that controls the use of Mr. Disney’s name.

Mr. Disney’s contract with Walt Disney Productions gave him a basic salary of $182,000 a year and a deferred salary of $2,500 a week, with options to buy up to 25 percent interest in each of his live-action features. It is understood that he began exercising these options in 1961, but only up to 10 percent. These interests alone would have made him a multimillionaire.

Once in a bargaining dispute with a union of artists, a strike at the Disney studios went on for two months and was settled only after Government mediation.

This attitude by Mr. Disney was one reason some artists disparaged him. Another was that he did none of the drawings of his most famous cartoons. Mickey Mouse, for instance, was drawn by Ubbe Iwerks, who was with Mr. Disney almost from the beginning.

Mr. Iwerks insisted that Mr. Disney could have done the drawings but was too busy. Mr. Disney did, however, furnish Mickey’s voice for all cartoons. He also sat in on all story conferences.

Although Mr. Disney’s power and wealth multiplied with his achievements, his manner remained that of some prosperous, Midwestern storekeeper. Except when imbued with some new Disneyland project or movie idea, he was inclined to be phlegmatic. His nasal speech, delivered slowly, was rarely accompanied by gestures.

Walt Disney was born in Chicago on Dec. 5, 1901. His family moved to Marceline, Mo., when he was a child and he spent most of his boyhood on a farm, where he enjoyed sketching animals. Later, when his family moved back to Chicago, he went to high school and studied cartoon drawing at night at the Academy of Fine Arts. He did illustrations for the school paper.

When the United States entered World War I he was turned down by the Army and Navy because he was too young. So he went to France as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross. He decorated the sides of his ambulance with cartoons and had his work published in Stars and Stripes.

After the war, he worked as a cartoonist for advertising agencies. When he got a job doing cartoons for advertisements that were shown in theaters between movies, he was determined that that was to be his future. In 1920 he organized his own company to make cartoons about fairy tales. At times he had no money for food and lived with Mr. Iwerks.