The summer of 1932 brought romance to the Giacometti household in Maloja. Not to Alberto, but to several of those close to him. Too close for comfort in one case.

Bianca had long since reached marriageable age. Attractive, vivacious, she liked a good time, laughter, parties. Young men paid attention to her, and she enjoyed it, but she still felt an intense attachment to her brilliant cousin. However, it was clear that nothing more positive than conversations or an occasional caress would ever exist between them. Alberto may have been resolved to remain unmarried; Bianca was not. She became engaged to a warmhearted Neapolitan, an enthusiastic supporter of Mussolini, named Mario Galante. They were married the following year.

Bruno Giacometti had begun the practice of architecture in Zurich, where he met and became engaged to an attractive young woman from Lausanne named Odette Duperret. The marriage turned out to be a particularly long and happy one. Odette was a good-natured, affectionate wife, attentive to the needs of her energetic and sensitive husband. Bruno possessed neither the creative genius of Alberto nor the bohemian temperament of Diego. His life was orderly and relatively uneventful, his career distinguished. In time he would design a number of buildings of ingenious beauty. He and Odette, like all members of the family, recognized the uniqueness of Alberto among them and were usually prepared to make allowances for it. Sometimes he put their patience to severe tests, but he never failed to repay it with gratitude and love.

The reputation of Giovanni Giacometti in Switzerland had by 1932 become so widespread that uninvited admirers often presented themselves at his home to pay their respects. One of

these was Francis Berthoud, a young doctor from Geneva. Not only a lover of art but also a passionate mountain climber, he had come to scale some of the more difficult neighboring peaks. He urged the young Giacomettis to accompany him. As Diego always enjoyed a risk, he and Francis went for quite a few climbs, while Alberto stayed home and fretted for fear that his impetuous brother might have a fall. So it was that Dr. Berthoud became familiar with the Giacometti household. Ottilia was then twenty-eight, pretty, sociable, and unmarried. The two took to each other quickly. Their intentions proved serious. The Giacometti family was pleased. An engagement was soon announced.

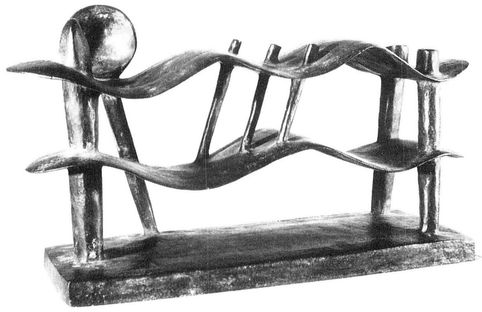

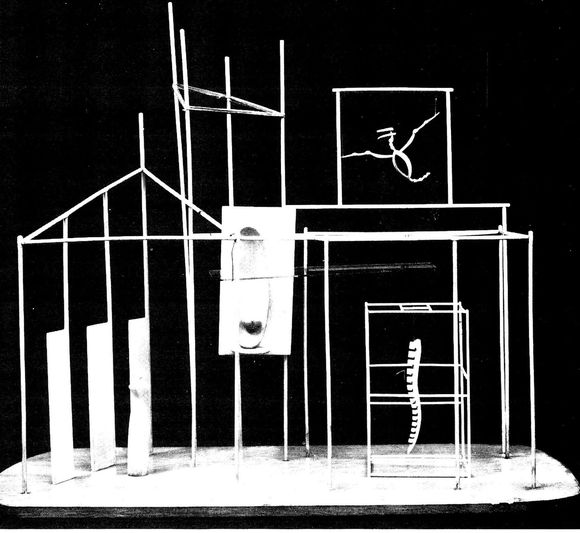

While the lives of persons close to him were being adapted to the comfort of social norms, Alberto continued to feel that he was not living fully and that he must make a life for himself more and more through his work. The Palace at 4 a.m. is one of the most eerie and enigmatic of all his sculptures. Made of wood, wire, and string, with a small rectangle of glass dangling in midair, it looks like the maquette for a stage setting in which some dramatic action may have occurred, may be occurring, or may be about to occur. At the rear rises a tower, unfinished, it would seem, or in ruins, brooding above the scene below. To the right, framed in a window, hangs the skeleton of a flying creature, and below it, inside a cage, a spinal column. Mounted on a slab in the center is an erect phallic shape, while to the left a stylized female figure stands before three upright panels. The whole structure has an air of being suspended in space, and if it is actually a palace, and the hour 4 a.m., then the concept is a dream. It conveys a sense of mystery, of strange foreboding, and Giacometti meant it to, because he published a text purporting to describe its genesis and hint at the significance of its cryptic iconography.

We are told that The e Palace at 4 a.m. is related to a period of the artist’s life which had come to an end one year earlier, when he passed six entire months hour by hour with a woman who made each instant a marvel for him and with whom he spent every night constructing a fantastic palace of matchsticks, beginning it over and over again as it repeatedly collapsed. During all this time, he writes, he never once saw the sun. The woman in question

was Denise, but his relationship with her had in fact not ended at all, and he saw the sun regularly. He had not yet begun to work till dawn, as he was to do later. Why a spinal column in a cage should appear in this palace, he declared, he could not say, yet he goes on to associate it with Denise. The skeletal flying creature is no more explicable, though it is “one of those she saw the very night before the morning when our life together collapsed.” It is in respect only to the stylized female figure that Alberto was able to be explicit. This was intended to represent his mother as he remembered her from earliest childhood, wearing the long black dress which had upset him because it seemed to be part of her body. The three panels behind her are supposed to depict a brown curtain which the artist claims to recall from infancy. The object in the center, erect and phallic, is also one concerning which it proves impossible to speak plainly. Alberto identified it with himself. In short, we have learned only that he and Denise are symbolically united in this fantasy structure where his mother, being the only specifically represented human figure, presides with serenity over the present and the past. Time and life seem to be suspended like the little pane of glass, fragments of emotion and experience trapped and caged forever. Ambiguity, if not ambivalence, prevails, and that, perhaps, is the troubling point.

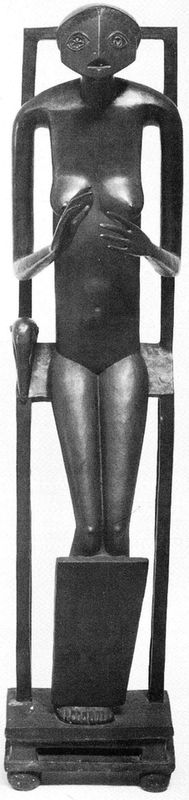

Between 1933 and 1934 Giacometti executed two almost-life-size figures strikingly anomalous in comparison to the other sculptures of his Surrealist period. Headless, armless, slenderly stylized, these figures are straightforward representations of a young woman’s body. One of them has a shallow, heart-shaped declivity just below the breasts, a singularity which emphasizes the delicate naturalism of the rest. Both figures have the left leg and foot placed slightly in front of the right and stand poised as in barely arrested forward motion. It is the precise, subtle placement of the feet, though they are of normal size, which determines the uncanny animation of these works. Each, indeed, is entitled Walking Woman. By their posture as well as by the power of their presence, they recall the sculptures of ancient Egypt.

The Giacometti family in 1909; Alberto, Bruno, Giovanni, Annetta, Ottilia, Diego (clockwise from left)

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1927

The Giacometti studio and residence in Stampa

Alberto in Rome

(clockwise from upper left): Torso, 1925; The Spoon Woman, 1926; The Couple, 1926; Personages, 1926

Alberto in 1922

Woman Dreaming, 1929

Alberto and Flora in 1927, with her bust of him

The studio complex in the rue Hippolyte-Maindron

Man and Woman, 1929

Isabel

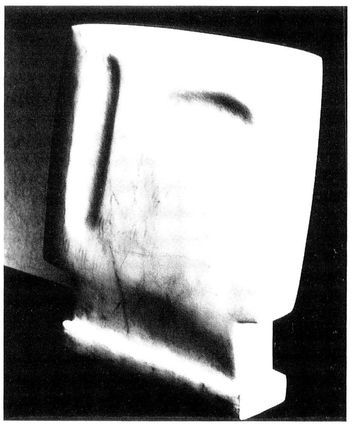

Gazing Head, 1927

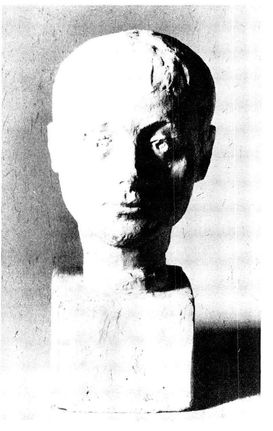

Giacometti’s first sculpture, a bust of Diego, 1914

Diego in 1934

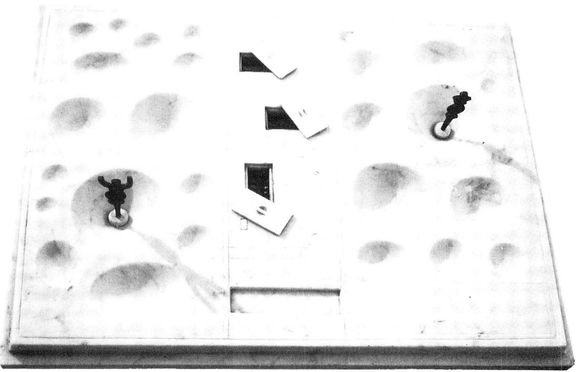

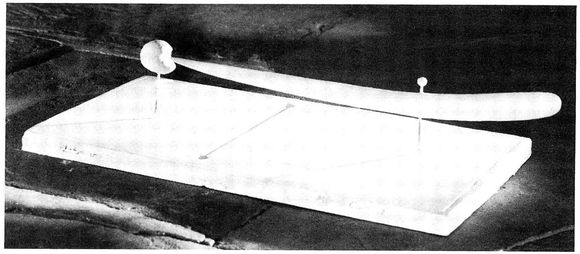

No More Play, 1932

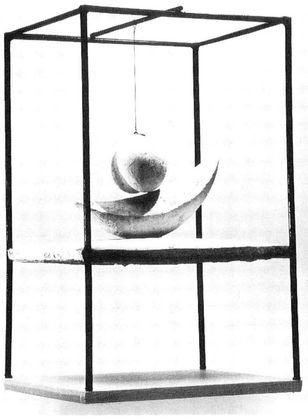

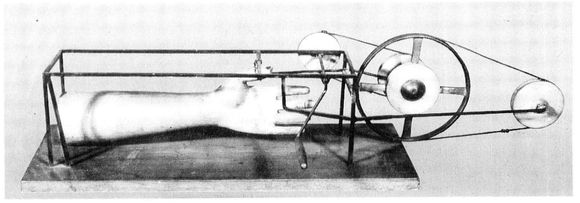

The Suspended Ball, 1930

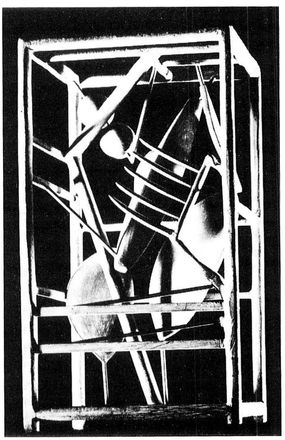

The Cage, 1931

Point to the Eye, 1932

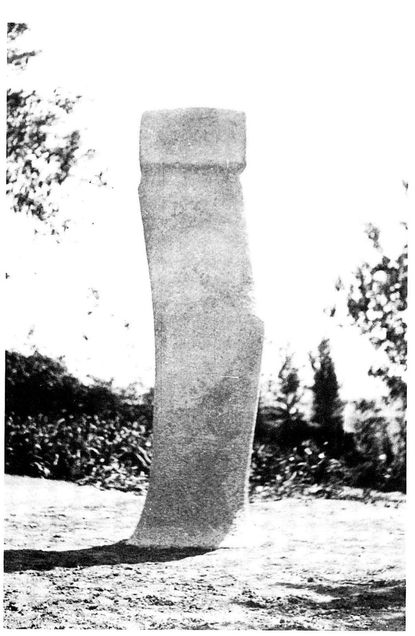

Figure, for the Noailles garden, 1932

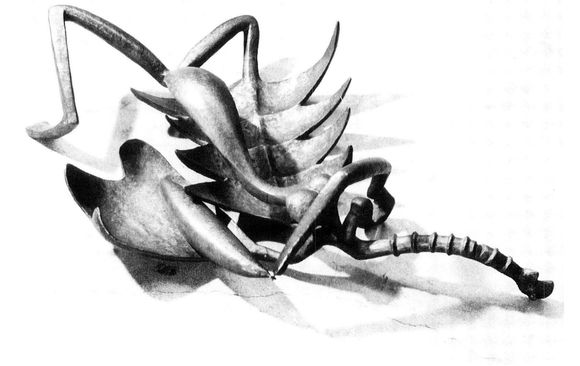

Hand Caught by the Fingers, 1932

woman with Her Throat Cut, 1932

The Palace at 4 a.m., 1932—33

Walking Woman, 1933-34

The Invisible Object, or Hands Holding the Void, 1934

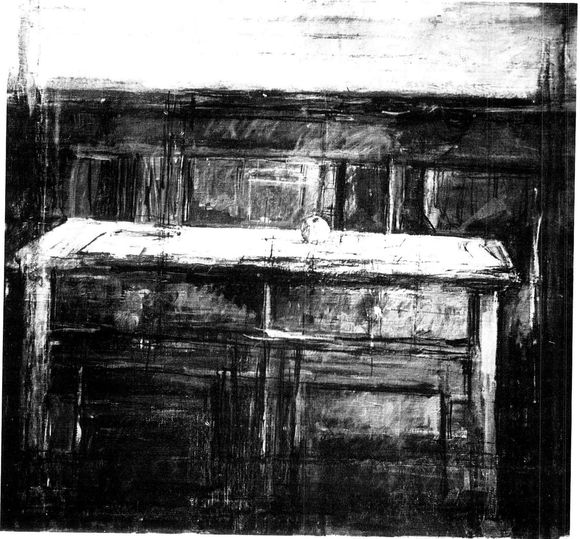

Apple on a Sideboard, 1937

The two Walking Women are openly alien to the spirit and purposes of Surrealism. Straightforward representationalism was heresy, and many had been excommunicated for less flagrant lapses. But Breton continued to be indulgent. Though he occasionally complained that Alberto was “undependable,” Giacometti continued to participate in the activities of the Surrealist group. An illustration of his readiness to do so may be found in one of his replies to the question asked by Breton in the course of a published dialogue. “What is your studio?” Breton asked. Alberto replied: “It is two feet that walk.”

In the month of May 1933 appeared the final issue of Surrealism at the Service of the Revolution. The demise of the movement’s evangelical publication may have been a symptom of impending decline. Alberto, who had contributed only a single text to previous issues, at the end contributed four. That fact may also have some terminal significance. Three of these are poems in the orthodox Surrealist mode, which is to say that it would be difficult, if not tendentious, to assign specific meanings. The first two, entitled “Poem in Seven Spaces” and “The Brown Curtain,” are short and virtually opaque. The third, “Ember of Grass,” is longer and more intelligible. One or two passages will illustrate with what evocative grace and refinement Alberto could write.

“I seek, groping in the void, to catch the invisible white thread of a throbbing marvel from which facts and dreams break out with the sound of a scream upon precious and living pebbles.

“It gives life to life and the gleaming play of needles and turning dice alternately fall and follow each other, and the drop of blood on the milk-white skin, but a strident cry suddenly rises, making the air throb and the white earth tremble.” In “Poem in Seven Spaces,” one space is given entirely to the phrase “a drop of blood.” The image apparently held special significance.

The last text by Giacometti which appeared in the concluding pages of that final issue of the Surrealist review was the invaluable document relating to his earliest memories, entitled “Yesterday, Quicksand.” The precision and vividness with which as an adult he describes the events, sensations, and fantasies of childhood might

lead one to wonder about their accuracy. The prevailing Freudian atmosphere of the Surrealist movement, moreover, might also prompt some question, because the revelations of the text fairly beg for Freudian interpretation. But the experiences described, and all of their implications, are so demonstrably and evocatively relevant to the nature of the mature Alberto that the issue of their fastidious fidelity to fact is beside the point, since the man, after all, is not the father of the child, and therefore could not counterfeit a credible likeness of himself.

What is apposite and strikingly significant about “Yesterday, Quicksand” is that the author cannot have failed to grasp the underlying meaning of what he had written. Thus, the text represents an important step forward in his career. To have written and—even more!—to have published it is further evidence that he was increasingly able to live with himself in full view of self-knowledge. But the fruits of self-knowledge, however vital to the growth of an individual, are not necessarily palatable to others. One cannot but wonder how they may have tasted in Stampa, for it is unlikely that such a public affirmation of their son’s prominence would have failed to receive his parents’ notice. Alberto’s memories of the cave, of the black rock, of the burrow in the snow, of the cozy hut in Siberia—all these could have seemed the innocent effusions of a poetic temperament. But what of the detailed fantasy of murder and rape with which the young boy found it necessary to regale himself before falling asleep? Devoted as she may have been to the advancement of her son’s career, Annetta Giacometti was not a woman who could have learned with equanimity that her young son had enjoyed such lurid imaginings. As for Giovanni, already convinced that Alberto’s Surrealist work was a mistake, this public declaration of a taste for violence and murder, however literary, can hardly have been pleasing.

Giovanni Giacometti was sixty-five years old. Recognized and admired as one of the leading painters of Switzerland, he had come a long way from the hardship and despair of his youth. Maturity had not been accompanied by creative fulfillment of the highest order, but perhaps he was unaware of this. His paintings

were widely exhibited and purchased. Maybe that brought satisfaction enough. Besides, he found himself growing tired. He looked older than his age. Prolonged physical effort had become increasingly difficult. A doctor of his acquaintance named Widmer, who had bought a number of his paintings and who owned a sanatorium at Glion in the mountains above Montreux, suggested that the weary artist come there for a rest. Giovanni agreed. A rest, however, was all that seemed necessary. The doctor assured the family that there was no reason to worry. Annetta accompanied her husband to the sanatorium. After a short time, feeling improved, he asked her to go to Maloja and open the house there for the summer.

On the 23rd of June 1933, Giovanni suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and lapsed into a coma. Annetta hurried back at once from Maloja, Bruno from Zurich, Ottilia from Geneva. They arrived at Glion the following day. Though the patient remained unconscious, there appeared to be no immediate danger. Hoping for improvement, the three decided not yet to alert Alberto and Diego.

The next day was a Sunday. Rain was falling on the mountainsides, on the forests, and on the fields around the sanatorium. At the bedside of the sick man, Annetta, her daughter and youngest son waited. As the hours passed, it became clear that Giovanni, who had never regained consciousness, was dying. Bruno notified his brothers in Paris. No such convenience as a telephone existed in their studio, but the message got through. They took the night train from the Gare de Lyon.

Alberto felt unwell as the train rolled eastward toward Switzerland. His malaise was an indefinite feeling of infirmity and fatigue, rather than a specific symptom of illness. He cannot have been in doubt concerning what awaited him in the rainy mountains above Montreux.

Bruno was at the station in the morning. He told his brothers at once that their father had died. Then the three of them drove together up into the mountains. It was still raining. When they arrived at the clinic, they were greeted by Annetta and Ottilia.

All five together, the mother, her three sons, and her daughter, went to the room where Giovanni Giacometti, their husband and father, lay dead.

Alberto soon announced that he felt sick, feverish, and would have to go to bed. A nearby room was available and Dr. Widmer made an examination. It disclosed that the patient did, indeed, have a fever, though this was due to no discernible infection or assignable malady. Rest seemed to be the only sensible prescription. Alberto remained in bed.

More practical and less emotional than his brothers, Bruno was the one to make arrangements for the removal of their father’s body to Stampa, the funeral and burial in the churchyard of San Giorgio at Borgonovo, where Giovanni’s own father and many relatives already lay. These arrangements had to take account of considerations beyond the feelings of the family, for the death of Giovanni Giacometti was an event of national importance. Newspapers were prompt to print eulogistic accounts of the artist’s career, and his passing was noted as a loss to the cultural life of the country. It was proper to expect that his funeral would be an occasion to express national pride as well as to pay homage to the dead man. The family was notified that a government representative would be present at the ceremony.

While Alberto remained in bed, Bruno went several times to his room to consult him about the arrangements. The older brother would have no part in them. Lying rigidly outstretched under the bedclothes, he did not respond. This apparent refusal to be concerned in an event of major importance to the family was surprising, especially as the eldest son by tradition took the place of the father upon the latter’s death. However, Alberto’s illness could be assumed to explain his strange behavior.

The following day, the family prepared to leave Glion with Giovanni’s remains for the journey back to Bregaglia. Alberto said that he was as yet too ill to travel. The others had no choice but to go on as planned. He would join them as soon as he was physically able. This, it turned out, was not until after Giovanni’s funeral. So Alberto was not present to honor the artist or make the final gesture of piety as a son. One cannot but wonder about

the nature of the illness which confined him to bed during those critical days, and speculate concerning his thoughts while he lay there alone, separated from the central figures of his life, who were busy performing the rites appropriate to one of its crucial events.