“In a burning building,” Alberto once declared, “I would save a cat before a Rembrandt.” That order of priority expressed a reverence for life. It also spoke for an awareness that art amounts to little in the balance of living and dying. However, the artistic work demanded submission to its needs even as their fulfillment seemed to entail a kind of disregard of himself, in the first place, and, in the second, of those whose proximity, and feelings, made them most vulnerable to disregard. He had no choice but to live as best he could with this contradiction, but he did not expect anyone else —except Diego—to do so. “What I am looking for,” he said, “is not happiness. I work solely because it is impossible for me to do anything else.” That was all very well, and all to the good, for him. But one who has little care for his own happiness is ill suited to provide for the happiness of anyone else, and if he is a man of conscience, he will take pains to avoid becoming responsible for it.

Annette had longed to be set free from the lacerating anonymity of a bourgeois background. To that end, and to just the extent necessary for seeming entitled to it, she was ready to suffer. In fact, it may be that that is what she was best, and most, prepared to do. Putting one’s background effectively behind one takes intellectual resolve and a character of solid rock. Annette had only her longing, which perversely but constantly put the background into the foreground. Five years with Alberto had only intensified her desire for a domestic setup that would satisfy the standards of Grand Saconnex. The case was complicated rather than eased by their devotion to each other. Love, however, cannot save lovers from their faults.

Annette wanted to get married. That should have been unthinkable.

But she didn’t think. Having become important to her lover in his work as well as in his life, she must have assumed that she could risk putting her importance to the test. It was too bad, because that test in the long run could have only one result, and the risk for her was final. She appreciated his importance greatly, since she loved him, and her appreciation seemed to be the logic of her claim, but she understood very little about his significance, since it had nothing to do with love. The grounds for union were, consequently, shaky. And yet she was tenacious in pursuit of matrimony. Her lover turned evasive. The thing was difficult for both.

Alberto knew that the maker of decisions must accept responsibility for them. And he knew that nobody has ever been entirely free to make choices, to measure prospects for satisfaction, or to judge accurately the wisdom of decisions affecting not only himself but others. In addition, the institution of marriage as a symbol of right human relationships put an intimidating weight on the mind of someone who knew that he could never wholly fulfill the natural expectations of a wife. Moreover, being a husband would be a damn bother, because he had work to do which admitted no other right to his time or energy, and it did not ask for anybody’s approval or affection. He hesitated. He said, “The easiest thing in the world is to take a wife, and the most difficult is to get rid of her.” But there was his mother to be considered, and Alberto never needed urging to do that. Annetta had come to favor her son’s marriage because she deemed that state fitting. He knew that he could never bring his mistress to his mother’s home as long as they remained unwed. And now that she had become his model he would have liked to take her along to Bregaglia, where she could continue to pose. He would also have liked to please his mother. And, as a matter of fact, he would have liked to please Annette. But how was he to reckon the needful balance between doing as others wished and being as he must? No wonder he hesitated.

Hesitation led to crisis. Alberto resolved it, with the sanction of creativity and genius, by saying yes. He had always said yes to life. “Yes” was the answer of the artist, the response of a man dedicated to doing, proof of his devotion to the positive. By agreeing to marry, he agreed to give a fuller measure of his humanity, and his

decision reflects an appreciation of the contribution Annette had already made to that measure. The forty-seven-year-old artist had experienced a rebirth, had generated new life in his work, and it should not be astonishing that in his personal life he found himself prepared to accept the adoration and companionship of a woman twenty-two years younger. However, he wanted it clearly understood that nothing would be changed. He insisted on it: Annette was not to assume that the formality of marriage would in any way alter their relationship or make a difference in their behavior. He had insisted that her coming to Paris should make no difference. Here, nonetheless, was prima facie evidence to show how different everything had become. But she could easily agree that nothing would change, in the knowledge that her own metamorphosis was to be so radical. One day the issue of their sincerity would weigh heavily in the balance.

Alberto’s betrothal came as a stunning surprise to his entourage. For those who had been treated to his tirades against everything marital, to his scorn for conjugal sentiment as wishy-washy compromise and his paeans in praise of prostitution, the news was a rude shock. Even Diego was taken aback; years later, in enduring bemusement, he occasionally said, “She really must have worked him over to get him to marry her.” And indeed the business presents a puzzle. “Yes” may have been the artist’s answer to life, but Alberto’s life was wed to art; it asked questions to which workaday experience held no reply; its commitments needed no formal vow to be binding. Contradiction, however, is at the core of an artist’s being, because he thrives on the infinite multiplicity of possible choices. But only his being is at stake in this ceaseless confrontation of alternatives. Allowing someone else to come into it can be perilous. But that is just what Alberto agreed to do. People wondered why. An explanation of sorts was given a decade or so later by the artist himself to the woman who replaced Annette in the center of his life and became for him the climactic incarnation of feminine allure, mystery, and divinity. When she asked how he had come to marry, he said that his agreement had finally been given when Annette declared that otherwise she would kill herself. If so, how serious she was we can never know. The

chances are she didn’t either. As she saw her hopes continually deferred, there arose, perhaps, a sense of despair all too familiar from the past, proving yet again its inescapable dominance. By declaring that she would do away with herself if Alberto refused to marry her, she may merely have affirmed her conviction that the self with which she could do as she would was so completely dependent on him that his refusal must bring an act of total negation.

No matter what Annette said, thought, or felt, the positive commitment to marriage was made by Alberto alone. He knew that, and knew he had the resources to stand by it. Whatever the cost, he could, and would, meet it. But he had no way of knowing whether he could count on the resources of the one who had solicited his commitment. In fact—and this is just where he went wrong—by asserting with such insistence that the marital state must never be construed to have altered anything between himself and his wife, when he cannot have failed to expect that it would alter everything, Alberto seems to have needed to emphasize that he was taking a step directed toward destiny more than matrimony. And so he set foot on terrain where neither wisdom nor caution could guide him. He had been at fault in permitting Annette to join him in Paris. He compounded the fault by consenting three years later to marry her. But the fault—like the knowledge of his commitment —was entirely his, and he never tried to shift or shirk it. He met the cost, which turned out to be almost as great as the value added to his art.

There was a legal nicety. Marriage in France means that both parties, citizens of another country or not, are subject to French marital law. It stipulates that all property is held jointly by the couple unless at the time of marriage they sign a contract specifying that each is the sole owner of his, or her, property. In other words, without such a contract, Annette as Alberto’s wife would take legal title to half his work. Displeased by that prospect, he insisted that the contract be part of the marriage act. He obtained the necessary document. But then, as so often when a prudent decision called for practical application, he didn’t bother to pursue it.

Needless to say, anything remotely resembling a ceremony was out of the question. The event itself would be more than ceremonial enough. Alberto did make one concession. He got out of bed early. It was Tuesday, July 19, 1949. In midmorning, the bride and groom walked to the nearby town hall of the 14th arrondissement, accompanied by their witnesses, Diego and Renee Alexis (who had stayed on as concierge after the death of Pototsching). So Annette Arm and Giovanni Alberto Giacometti were married. When it was done, they went with Diego to lunch in a restaurant. Then Alberto returned to the rue Hippolyte-Maindron and got back into bed.

A honeymoon would have been laughable, but later in the summer the artist took his bride to Maloja, where she was presented to his mother. The two Madame Giacomettis were predisposed to like each other. Annetta thought Annette “a nice girl,” though she observed that her son treated his wife like a daughter.

The years 1949 and 1950 were anni mirabiles for Giacometti, wonderful in the wealth, diversity, and mastery of works produced. One after another, the most extraordinary productions emerged from his studio. They include at least a dozen of those by which he remains most vitally present among us. To try to say how this came about would be, perhaps, to do away with an essential part of it. The artist himself, though, deserves to be heard. In this context, as in so many others, Giacometti found penetrating observations to be made. “In every work of art,” he said, “the subject matter is primordial, whether the artist is conscious of it or not. A greater or lesser degree of plastic quality is no more than evidence of the degree to which the artist is obsessed by his subject matter; form is always the measure of this obsession. But it is the origin of the subject and of the obsession which should be sought …”

Thus, the artist would have us seek in the rationale of creativity a meaning to which he can accede only through the medium of our perception. It stands to reason. By that same token, we are bidden to look into his life and work as deeply as we can, and by

whatever means, in order to see the truth he forged. If we are perceptive enough, we may also catch a glimpse of ourselves.

There are too many extraordinary sculptures of 1949 and 1950 to allow for discussion of each. Among them all, however, there is one, perhaps, more extraordinary than the others by reason of having required him to be extraordinary. It asks the beholder to be extraordinary, too.

The town hall of the 19th arrondissement stands in an out-of-the-way corner of northern Paris. Thrown up during the reign of Napoleon III, it is distinguished mainly by an air of bogus majesty, and only the portico is reminiscent of architecture favored by the first and more forceful Bonaparte. The building faces a square, opening on its southern side toward a public garden, the Parc des Buttes Chaumont. The center of this square had been occupied before the Second World War by a pedestal bearing the bronze statue of an obscure French pedagogue named Jean Mace. During the Occupation, the Germans collected many statues throughout France to melt them down, and that of Jean Mace was one of these. The post-war plethora of empty pedestals was seen as a symbol of national shame. Sculptors were solicited to supply replacements. The memorial to Jean Mace cannot have had a high priority, but the authorities got around to it in time. Partly at the behest of the ever more influential Aragon, and with the support of a minor Surrealist named Thirion, the sculptor selected to submit a project for that particular pedestal was Alberto Giacometti. It was a preposterous choice, and that should have been evident to all concerned. But no. Everybody seems to have found the project perfectly natural.

Alberto set to work. The memorial to the forgotten pedagogue must have been on his mind, but his creative faculties were clearly not disposed to entertain such a trivial prospect. What seized upon his imagination and held it without a qualm was the unique opportunity of executing a public monument for a square in the city of Paris. That opportunity produced the work of art, and its supernatural likeness to the conditions reigning over its creation. That likeness drove the sculptor to make a work incapable of seeming acceptable to anybody but himself. He began with a female figure, which showed from the start how little he cared about Jean Mace. This figure is much like others executed at the time, large-footed, tall, and slender. But there is an important difference. Her long, spidery arms are held well away from the body, giving her a surprising air of movement, enhanced by another dramatic innovation: she stands poised upon a chariot. It is a real one this time, a true chariot, not the small-wheeled contraption added to the sculpture of 1943. This Chariot is not an idea but a fact. Its two high wheels are as important to the figure as the figure is to them. The wheels are joined by an axle from which two struts rise to support a platform where the passenger stands surprisingly still and straight. Being two-wheeled, The Chariot also bears the associative significance of antique counterparts and mythological intimations. Each wheel has four spokes: an apt aesthetic choice, it seems, until we remember the similar vehicle from ancient Egypt that the young artist had run into thirty years before in an Italian museum. The adaptability of his memory can be assumed to have had more effective uses than our own.

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1937

The Chariot (first version), 1943

Sculptures in the artist’s studio, 1946

Man Pointing, 1947

Night, 1946

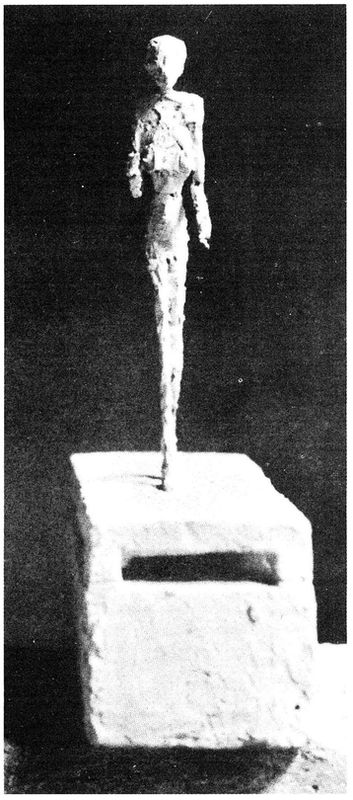

Tall Figure, 1949

The Nose, 1947

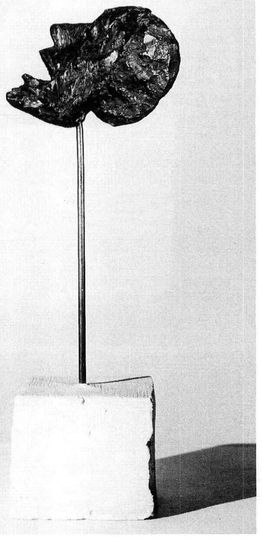

Head on a Rod, 1947

The Chariot, 1950

Alberto, Annette, and Diego in the studio, c. 1952

The City Square, 1949

Women of Venice, 1956

Yanaihara, 1958

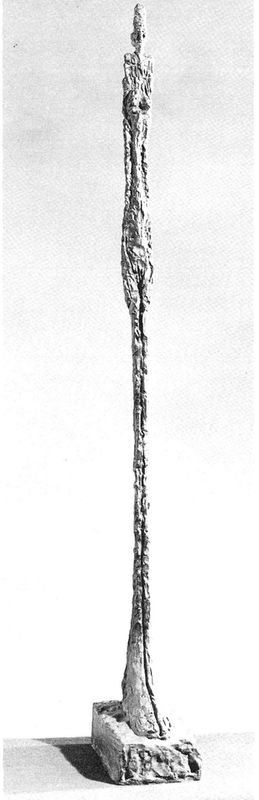

Tall Figure IV, 1960

The Leg, 1958

Walking Man 1, 1960

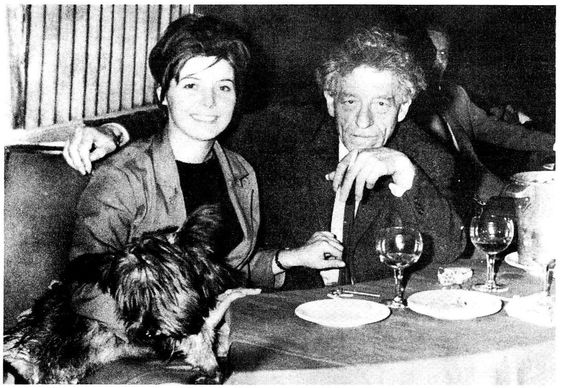

Alberto and Annette in the café on the corner of the rue Didot, c. 1960

Annette IV, 1962

Caroline, 1965

Annette, 1962

Alberto and his mother at Stampa, 1961

Alberto and Caroline with her dog Merlin, c. 1963

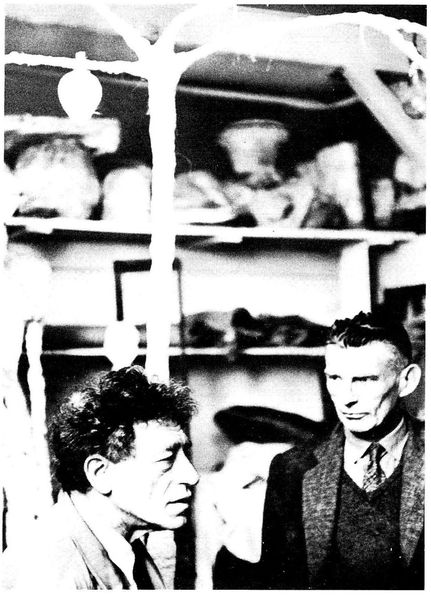

Alberto and Beckett with the tree for Waiting for Godot, 1961

Alberto in 1961

Alberto’s tomb in the graveyard at Borgonovo, with the final bust of Lotar

Of all the works executed by Giacometti, The Chariot may be the most hieratic and mysterious. Poised in midair, the delicate but dynamic figure appears to command our attention as much by her unapproachable majesty as by the serene equilibrium with which she remains motionless and upright, while at the same time suggesting to an uncanny degree headlong motion. How different she is from the earlier sculpture of the same name, of which the wheels were negligible in size. This later, greater mounted woman is infinitely more ambiguous and arcane. The first could conceivably be grasped in her suggestive purpose, while in approaching the second, every step must be measured with prudence. She seems to beckon just as she bids one to stay safely at a distance. It is the wheels, their size and their form, together with the position of her arms, which make and maintain the mystery. Because, in fact, she cannot move, though it is by the evocation, the threat, the menace of movement that she is so powerfully present. Immobile, she is motive. Inert, she nevertheless acts. Her identity is concealed even

as it is revealed. Naked, she is clothed in an aura of taboo. She wears her femininity like armor. Mounted on a warlike vehicle, she is above the encounters and accidents of everyday life, to which, though they are in her path, her indifference is absolute.

This was the sculpture Giacometti intended to place in a public square in Paris to serve a commemorative purpose. Only he could have taken the idea seriously. The men from the 19th arrondissement were shocked. The artist and his work were sent packing. Unabashed, Alberto returned to his studio. The opportunity had been all. The outcome could take care of itself. The plaster sculpture was soon carted off to the foundry to be cast in bronze. Six casts were eventually made, and it is worth noting that most of them have a gold patina, though he ordinarily favored dark bronze. The Chariot called for association with the metal most prized by man, the first to be worked in the pre-dawn of history, the one most often used to make or to enrich the effigies of heroes, saints, and deities.

But this was not all. The artist felt constrained to make an explanatory statement. The Chariot was exhibited for the first time at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York in November of 1950, along with a score of other sculptures, plus paintings and drawings. In an effort to make more clear the titles given to various works, Giacometti sent illustrated notes, some of which were reproduced in the catalogue. “The Chariot could also be called The Pharmacy Cart,” he wrote, “because this sculpture comes from the tinkling cart I marveled at when wheeled through the rooms of the Bichat Hospital in 1938.” Maybe. The cart, however, of which he had made drawings was the one in the Remy de Gourmont Clinic. But the little lapse of memory could be only a coincidence, and he went on to say: “In 1947 I saw the sculpture as if it existed before me and in 1950 it was impossible for me not to make it, though situated for me already in the past. That is not the only reason which drove me to make this sculpture. The Chariot was executed from the necessity once more of having a figure in empty space in order to see it better and to situate it at a precise distance from the floor.”

If the explanatory statement was really provided for our perception,

and if we are really meant to take the measure of form through the intensity of the artist’s obsession, then the pharmacy cart by itself would not go far. Farther, and faster, would proceed an inkling that emerges from the roots of language, for we find that in French a two-wheeled metallic vehicle without a body, carrying one person, is called a spider. Like a dream, The Chariot moves inward upon itself even as it seems to rush ominously forward, and in our perspective this motion signifies that the sculpture was not created by accident. Art uses life, and the extent of the use gives the moral of the work. The Chariot leads us to look more closely than usual at this interaction. It is fascinating but frightening. Where first there was nothing, suddenly there is everything. Giacometti was right in bidding us to seek in his work meanings recognizable only insofar as we can discern them to be evidence of our discernment. That was why, and how, he could say, “Art interests me very much, but truth interests me infinitely more.” His interest was to be richly repaid, especially on the second score. So will be ours, albeit fortunately not in the same currency.

“The motor that makes one work,” Alberto once observed, “is surely to give a certain permanence to what is fleeting.” He then went on to remark that the impulse was effective for everyone, even for those who do no more than relate the events of a commonplace day to friends or family, since in the narration the events are re-created, perpetuated, and given a new reality. So, he said, everyone makes art in a way, every story being created anew each time it is told. The outcome for most of us is nothing but a lifetime, of which the significant events are in a state of ceaseless flux as we relate them to others and to ourselves. Even men who once ruled the world, whose acts are the fabric of history, even Caesar, even Napoleon, have felt bound to give accounts of themselves, knowing better than most men that yesterday’s fact is not necessarily tomorrow’s truth. Alberto knew that, too, and in his way he gave definitive accounts. An ability to recognize as such the significant events of his life helped. It helped the accounts, that is, not him. For him a great deal of the significance dwelt in the difficulty of making the account definitive. What helped him, perhaps, was that the greatly significant events were few, so few we can practically

say that they were just two, allowing for the supposition that the smallness of their number also makes for the immensity of their significance.

About the death of the Dutchman, Alberto published an account, about the accident never, although toward the end of his life, when others had taken it upon themselves to do so, he is reported to have written a twenty-eight-page narrative to set the record straight. Just how straight the record could possibly have been set by Alberto is a tantalizing question. The document, if it exists, is not at our disposal. What we may lose by way of evidence is unlikely to be more than corroboratory, however, because Alberto had the record constantly in mind and often at the tip of his tongue. As if for fear that his lameness might escape notice—his own, perhaps—he went out of his way to talk about the night in the Place des Pyramides, repeatedly telling the story of painful months spent in hospital, all the while threatened with amputation of his maimed foot. Though he talked about the accident almost as if he had brought it upon himself, he was clear about his satisfaction with the outcome.

The Chariot was not the only masterwork of these years. By virtue of its extraordinary connotations, it seems the most extraordinary. But it may not be, and some of the others need mention. There were several sculptures of men walking, either singly or in groups. One of these, called The City Square, shows four men walking separately in various directions and one woman standing immobile, her arms pressed tightly to her sides. Several groups of standing female figures are set upon platforms, some with heads of men placed behind or to one side of them. The artist named one The Glade, another The Forest. The concept of trees as sensible beings is age-old, and vestiges of worship of tree spirits have persisted to the present day in various localities, including the English village where Isabel Lambert later went to reside. Other sculptures of these years show women standing alone or in groups on massive pedestals, the latter identified by the artist as prostitutes he had seen either at the Sphinx or in a small hotel room, where in the

first case he perceived them to be unapproachably remote, though desirable, and in the second very close, hence threatening. So, too, they appear to us. Distance was not the loan of enchantment but the gift of passion. None of these works was conceived as an effort to depict the artist’s immediate visual experience. Rather, they were made to be outward embodiments of inner states, whether conscious or unconscious, and as such they serve further notice that, while the expressive means and formal powers at Giacometti’s command had been greatly developed and deepened, yet certain essential themes of the creative discourse remained constant after twenty years.

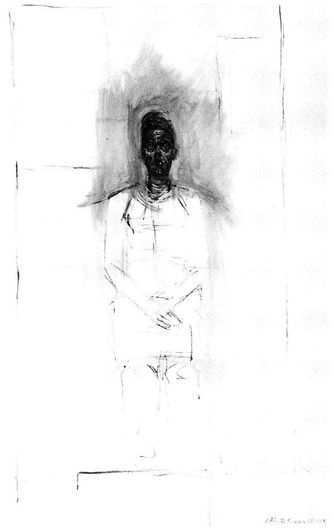

Simultaneous with this prolific production, and obviously impelled by newly evolving aesthetic intentions, Alberto pursued his efforts to make convincing representations while working from life. His wife, mother, brother, or an occasional friend posed for him. This pursuit was pressed principally in the direction of painting and appears to have proceeded without great difficulty. Numerous paintings of these years show increased boldness of vision and growing mastery of execution. The artist’s progress was divided almost equally between visionary introspection and objective visual concentration. The dichotomy may have arisen from the nature of what was to be expressed or from the expressive resources available. A single creative culmination would be the outcome of two techniques made to fuse in the representational unity of insight and intent.

The paintings of this period show the artist’s models integrated with their surroundings, neither isolated physically nor impaired spiritually. They cannot be taken for models of existential alienation or anxiety, as critics increasingly believed Giacometti’s sculptures to be. Alberto often found his efforts being described in terms of ideas and attitudes taken from his friends Beckett and Sartre. He protested occasionally. “While working I have never thought of the theme of solitude,” he said. “I have absolutely no intention of being an artist of solitude. Moreover, I must add that as a citizen and a thinking being I believe that all life is the opposite of solitude, for life consists of a fabric of relations with others.

The society in which we live in the West has made it necessary in a sense for me to pursue my activities in solitude. For many years it was hard for me to work isolated from society (but not, I hope, isolated from humanity). There is so much talk about the malaise throughout the world and about existential anguish, as if it were something new. All people have felt that, and at all periods. One has only to read the Greek and Latin writers!”