Born and raised in Iowa, I spent many summers working for my dad. He was a high school science teacher and a house and barn painter over the summer. He painted, he would jokingly tell people, so he could afford to teach. He still paints, even after retiring from teaching. (He would probably tell you he now paints to afford retirement.) There was one guy—Marvin—who had us paint his farm buildings every six or seven years. He was one of those farmers: kept his field rows neat and tidy, mowed ditches between the road and his crops, string trimmed fence lines, and took pride in having well maintained buildings.

I had the opportunity to visit Marvin during a recent trip back to the Hawkeye State. From the road, everything on his farm looked as I remembered. The buildings were still immaculate. “That’s one thing I can still control, when and what color they get painted,” he told me. Judging by that quote, you might be able to guess that something was amiss with Marvin’s operation.

“I didn’t sign up for this,” were the first words out of his mouth when I asked him how things were going. My earliest memories of Marvin date back to the early 1980s, when the farmhouse was new, furnished with the first VHS machine that I had ever seen. My sense at the time was that Marvin was rich. He wasn’t, though he admitted during our recent visit that “times then were a lot better, a lot better.”

Like many farmers, Marvin has seen his income steadily drop over the past decades. While average U.S. farm incomes have been eroding for generations, the rate of decline has picked up in recent years, falling 36 percent in 2015 and another 14.6 percent in 2016.1 Why Marvin has seen revenues drop is a complicated story.

When describing what he “didn’t sign up for,” Marvin talked about what it felt like to be on the losing side of both selling and buying power. His takeaway point: there is nothing free, or fair, about the markets that shuttle commodities through conventional foodscapes. Here’s a guy who has realized the Jeffersonian dream. He owns most of the land that he cultivates; let’s also not forget about those good looking farm buildings. And yet—well, let’s just say be careful what you wish for.

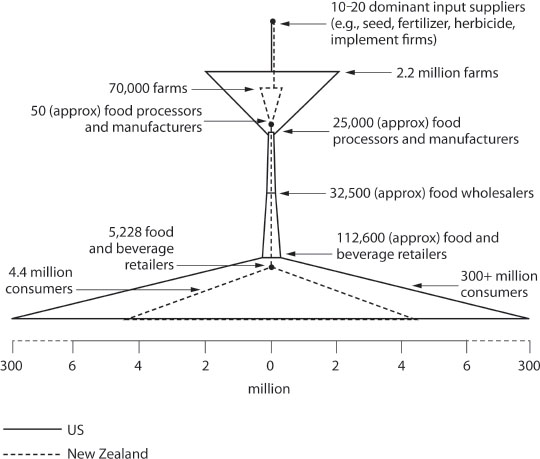

Marvin is stuck between a rock and a hard place: the rock being the very small number of firms that supply seed, fertilizer, and pesticides to farmers and the hard place being the highly concentrated market of food processors, manufacturers, and retailers to whom farmers sell. (This phenomenon is not unique to America; figure 1.1 superimposes the conventional foodscapes of the United States and New Zealand.)2

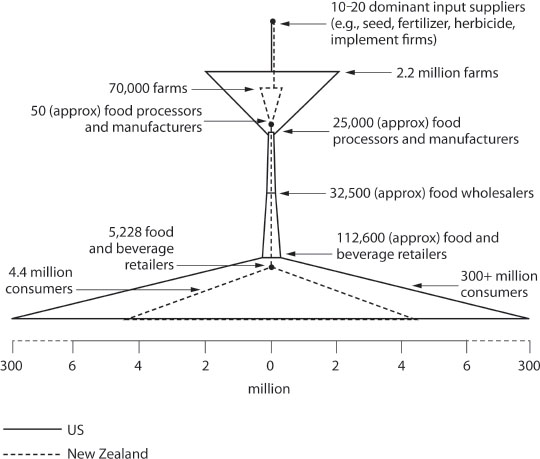

To see just how concentrated agricultural markets have become, take a look at a common measure: the four firm concentration ratio—or simply CR4. The CR4 is the sum of market share held by the top four firms in a given sector. A standard rule of thumb is that when the CR4 reaches 20 percent, a market is considered concentrated. Forty percent is highly concentrated. Anything past 60 percent indicates a significantly distorted market. As seen in figure 1.2, there’s some serious distortion in the U.S. food market, with rice milling at 85 percent and sugar refining at 95 percent. The level of concentration varies by commodity—the genetically engineered seed market is about as free as markets in North Korea.

FIGURE 1.1

Farmers today are dealing with both horizontal and vertical concentration. The CR4 statistic is a measure of horizontal concentration, which refers to concentration at one “link” in the food commodity chain. Horizontal integration occurs when firms in the same industry and at the same stage of production merge and dominate a market. Vertical concentration, meanwhile, describes the situation in which a single company owns an entire supply chain, as when a meat processor owns the slaughter facilities, hog farms, cornfields, and veterinary services and the transportation to move commodities from one link to the next. This is the situation Marvin finds himself in.

Figure 1.2 Concentration of U.S. agricultural markets (unless otherwise stated)

After giving me a tour of his buildings, Marvin plopped down on an old teeter-totter picnic table. (You know the type: one side lifts off the ground unless the weight is evenly distributed across both sides.) We were situated between a new farrowing house and an old but well maintained Quonset hut. With sows squealing in the background, Marvin took a long, deep breath and exhaled. The air rushed between his teeth and made a protracted whistling sound, giving him time to think, either about the actual answer or about the one he wanted to give me. I had inquired about how the business was holding out. Marvin is a proud person. The pause was likely born of reluctance, of his not wanting to risk coming across as complaining about the hand life has dealt him, even to a friend.

It did not come out immediately, but he eventually admitted to feeling “powerless,” adding, “The farm is mine, but at the same time it isn’t, if that makes sense.”

Some of Marvin’s angst lay in having made the transition, about ten years back, to contract farming. Before that, he was “a freelance producer of food.” Back then, he raised hogs and delivered them to whichever regional market was offering the best spot price on that day—doing what you might think all farmers do in order to sell their wares, if you didn’t know better. Things generally don’t work like that anymore.

Farming is all about timing, especially in livestock agriculture. Animals need to be sold the moment they reach optimum weight. To wait—to hold out, say, for a better price—is to waste resources (i.e., feed, space) that could be used for fatting up the next herd, litter, flock, brood, or clutch. Dairy producers need to have their bulk tank emptied daily, sometimes every couple of hours. When faced with these realities, farmers cannot hold out for a better price without severely undermining the economics of their operation, to say nothing of their animals’ welfare.

Because the market is so concentrated, meat processors have the power to lowball farmers. They know that the Marvins of the world cannot go looking to distant markets for a better price, not when the commodity in question might spoil or even die in the process. Shipping live animals over long distances increases rates of animal mortality. Even if the trip does not kill them, they will almost certainly suffer from what’s rather coolly known, given that we’re talking about live animals, as “carcass shrinkage.”

It was not long before Marvin told me about the terms of his contract. But before we could get far into the subject, one of his hired hands pulled alongside with a tractor to hook up to the Gehl Mix Mill that rested behind me. There is a lot to be said about tractors. But if I had to choose between the smell of hog manure and the smell of diesel exhaust, I would take manure every time. Between the noise and odor, Marvin and I agreed with a look and a nod to get up and walk toward the house.

With the racket receding and the sweet, nutty smell of manure once again filling our noses, Marvin returned to the subject of his contracts. With a dry laugh, he called them “the bane of my existence.”

Remember, this is someone who appears to be living the Jeffersonian dream. Marvin again: “I own 1,090 acres and rent another 400, which is more than I owned back when times were good. All the buildings, mine too.” At $7,633 per acre, the average price of Iowa farmland in 2016 (though Marvin’s land is definitely above average), his landholdings total more than $8.3 million. He has also invested more than $1.5 million in various facilities to raise his hogs.

Wait. Calling them his hogs isn’t quite right because, technically, they’re not.

“From the outside, I could see someone thinking that it’s a pretty equitable arrangement. Hell, I thought that way at first.” Marvin’s contract was structured a lot like the hundreds of others that I have been shown. The farmer supplies all the labor, land, and buildings, “Though,” Marvin was quick to add, “the facilities need to be built to very specific specifications, which means they can’t be easily repurposed for something else.” Meanwhile, the buyer supplies everything else: vet services, feed, transportation, and animals.

Marvin proceeded to tell me about the tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of new gestation crates that he was recently required to buy. Gestation crates, also known as sow stalls, are metal enclosures—Marvin’s were roughly six and half feet long by two feet wide—for female breeding pigs. They are usually found only in more intensive hog operations. The expense was made even more difficult to swallow in Marvin’s case, as the old crates “worked perfectly fine; they were just too large.” He explained that the change was made to “cram more sows into the farrowing barn.”

We could debate the welfare implications of this switch, not that I think there is much to debate. Cramming sows into even smaller spaces is a step backward, on multiple levels. This investment also made it exponentially harder for him to rethink his business model, especially if the alternative involved producing something else. You cannot really do much with gestation crates outside of hog production.

As we discussed his contract, an old saying kept coming to mind: the devil lies in the details. And those details in Marvin’s case were devilish. In negotiating his contract, Marvin never really had a chance. Processors have their pick of farmers. Meanwhile, farmers are lucky to have more than one buyer to select from. Farmers in these situations lack exit power, the power to walk away from the negotiating table, which means they lack leverage, making them price takers rather than negotiators. In Marvin’s case, his contract is structured in such a way that he is “getting less” than what he “used to receive back when there were a couple buyers to choose from,” like back when he was envied by an eight-year-old for his VHS player and twenty-inch-plus television.

I asked Marvin why he accepted such an arrangement. Having known him for more than thirty-five years, I felt comfortable taking the direct approach. His eyes immediately fixed upon his hands, almost as if he did not want to look me in the eye. Then, sheepishly, he answered, “I know; stupid, right? Yeah, I knew I wasn’t going to be making as much. But at least I knew I had a long-term contract. Beggars can’t be choosers.”

There you have it: market concentration makes beggars out of farmers.

I am not suggesting that processors are bad people. They are taking full advantage of the fact that farmers in these situations need their business. That dependence also increases over time, which was Marvin’s point when telling me about how his buildings were “built to very specific specifications, which means they can’t be easily repurposed for something else.”

Think back to those gestation crates—cages that have trapped Marvin every bit as much as his sows. When you invest $1 million into a facility with a thirty-year life and no practical alternative use, you suddenly have a million new reasons to renew your contract and a million reasons for overlooking how unfairly structured it is.

As if things couldn’t get worse …

On October 17, 2017, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced that it was withdrawing the Farmer Fair Practices Rules—or the Grain Inspection, Packers, and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) rules, as they’re more commonly known. The move was essentially the government giving the middle finger to farmers such as Marvin.

Marvin’s life would not have changed all that much had the rules been allowed to go into effect. But these Obama-era rules would have made it a little easier for livestock farmers to sue processors or meat-packers over unfair treatment by updating language in the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921. Farmers currently have little legal recourse to all the unfair treatment described here. Marvin’s buyers could tell him to build any sort of structure they want, no matter how outrageous. Noncompliance could be grounds for breach of contract and would certainly jeopardize contract extension.

Right now, and for the foreseeable future—thanks, USDA—Marvin would need to prove “competitive injury” if he wanted to take his buyers to court: a legal bar that would have been lowered considerably had the rule gone into effect. In practical terms, this means he would need to prove that a company’s actions against him harmed competition throughout the entire industry. This burden of proof is as irrational as it is insurmountable. It is like saying that if punched, you would have to prove that the assault harmed all of society in order to claim punitive damages from your assailant.

Farmers deserve better.

I met Jack during a thunderstorm, which seemed to portend the discussion that followed. Over coffee and cinnamon rolls, and between cracks of thunder, Jack told me a harrowing story.

A few years back, on a night not unlike the one unfolding beyond the dry confines of his house, Jack had heard a knock on his door. Answering it, he discovered two gentlemen. Claiming to be surveying area farmers on behalf of the state’s land grant university, they asked him a few questions. (They didn’t show credentials, and Jack didn’t ask to see them, midwestern hospitality norms being what they are.) The men were interested in the seed he had planted in recent seasons, the herbicides he had used, and where he had taken his crops after harvest. Then, as quickly as they had appeared, the men thanked him for his time and turned back into the rain, never to be seen by Jack again.

It took six days, and some sleuthing on his part, to discover their true identities. Turns out they’d been asking questions around town about him. These visitors were investigators for Monsanto, an agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology company.

Parts of Jack’s story sounded like something right out of the Jack Reacher series by Lee Child: clandestine agents lurking in his fields trying to obtain unauthorized seed samples, and Jack, never far from his shotgun while doing chores—purely for intimidation, he assured me. I could not verify that anyone actually trespassed, though I did see two large RedHead gun safes in Jack’s machine shed, right next to a reloading bench with a shotgun shell press.

Monsanto does not inspect all the farms using its products. The company’s pockets are deep, but not that deep. Typically, it works from information gleaned from its tip line. The company strongly encourages farmers to report neighbors they suspect of using its seed unlawfully—generally anytime Monsanto’s seed is saved and replanted.

We are talking about seed the farmers bought. Seed that will produce new seed, which farmers will then harvest, with their own sweat and equipment. Seed they will then take to a grain elevator to sell, presumably because it’s theirs. Right?

Farmers effectively sign away their ownership rights the moment they buy most commercial seed. Remember what I said earlier about the devil being in the details of contracts. Seed use agreements are devilishly detailed. All farmers using Monsanto’s products must sign a Monsanto Technology/Stewardship Agreement, wherein they agree to a list of stipulations. To quote directly from one such agreement dated a few years back, users agree to things such as these:

Note the openness of this language: records and receipts that could be relevant to the agreement. This essentially gives Monsanto access to any and all paperwork linked to a farmer’s business.

There is one additional stipulation in the agreement worth highlighting. Located in the section titled “Grower Receives from Monsanto Company,” farmers are said to receive “a limited use license to purchase and plant seed containing Monsanto Technologies (‘Seed’) and apply Roundup agricultural herbicides and other authorized non-selective herbicides over the top of Roundup Ready crops.”

Jack swore that he did not violate any of the agreement’s terms. And yet, he settled out of court. When asked why, all he could initially muster, a whole octave higher than his normal speaking voice, was, “Me take on Monsanto—are you nuts?” What the actual terms of his settlement were, he would not say. Settling sealed his secrecy on the specifics, thanks to a nondisclosure agreement written by Monsanto attorneys.

You might think such an experience would have given Jack pause, enough even to change management practices, maybe even occupations. You might think that, if you didn’t understand farmers. It is easy to confuse stubbornness with pride, inflexibility, and independence. It is not being stubborn to protect one’s own house, family, and lifestyle. Wars have been based on less than that.

Jack also admitted to farming pretty much as he always has, minus the Monsanto products. Whether it is his choice to stay the course is a matter for debate.

I asked him directly how he might change his operation if he could. Just then, a loud clap of thunder sent our backs upright. Our muscles loosened as the sound waned, rolling off into the distance.

Jack resumed looking into his coffee as though there weren’t a question left unanswered. I knew he was thinking, so I amused myself by surveying the collection of U.S. President plates displayed in a nearby hutch.

Still staring into his mug, Jack continued: “There are days when I think about changing how I farm. But let’s get real. I’ve got loans to pay off, landlords too. I can’t grow anything I want, not without a market. And I’m just one guy, so I don’t exactly have leverage to shape markets. My hands are tied.”

Our interview concluded in typical fashion, with me asking if he would like to add anything. He blew out air through his mouth, scrubbed a hand across his face, and then took a deep breath, through his nose this time.

“You would think I’m in control of my destiny. I have land and buildings, good ground, lots of good equipment. My debt is a fraction of what some of the guys around me are grappling with.”

I wasn’t quite sure what Jack was building toward, but at this point he looked up and ran both hands through his hair, from front to back. Only then did I notice how bloodshot his eyes were. They hadn’t been like that earlier. The man before me was clearly frustrated.

“There are times I regret having it all. Having all this can feel more like a burden when it should be freeing. How f*cked up is that?”

Jeb is a corn, soybean, and wheat farmer living in central Nebraska. Now in his mid-forties, he has lived his whole life in the same house, save for the four years when he was getting his degree in agricultural economics at the University of Nebraska. I was visiting the state to learn more about its proposed Fair Repair Act, which was introduced into the Nebraska legislature in January 2016. Some farmers are trying to reclaim the right to fix their own equipment. Not a wild proposition, as this population includes the original do-it-yourselfers. As for folks like Jeb—farmer by day, right-to-repair activist by night—they are leading the charge to reclaim that right.

It’s funny—sad funny, not ha-ha funny—how agriculture went from being an inoculant from dependence to a path into it. We have already seen how structural changes to markets have made farmers dependent on processors. The Fair Repair Act looks to tackle a different type of dependence, specifically farmers’ reliance on dealers and other approved technicians to keep their equipment running.

The federal Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA), passed to prevent digital piracy, is a key piece of legislation in this story. It effectively made it illegal for equipment owners to access the software that runs their equipment. In practical terms, it meant that after 1998, farmers must have implement dealers perform work in which the equipment’s engine control unit is accessed. As there are few repairs that can be done on farm equipment that do not also require cracking into its computer, the resulting dependence has created yet another reliable revenue stream for farm implement firms.

There are practical reasons for wanting to be able to fix your own equipment or to have the option of having someone other than an “approved” technician do it. As Jeb explained, “Sometimes there’s nothing mechanically wrong with the equipment. Something gets tripped and the entire system shuts down and needs to be reset. So I lose two days of work and a couple hundred bucks to have some guy come out and hit a few buttons.”

He proceeded to tell me about when the transmission went out in one of his tractors. His neighbor, Nick, is a diesel and transmission mechanic and “a hell of a guy,” Jeb assured me. As he had done dozens of times before, he looked to Nick to be his repairman. No harm, no foul, according to federal copyright legislation. While John Deere would have undoubtedly preferred that he have his equipment repaired at one of its dealerships, there was not much it could do. The tractor was no longer under warranty. And we’re talking about a transmission repair, not a software upgrade.

“But then,” Jeb said, “we got the transmission installed.” I looked up at him, expecting him to say more. His eyes met mine and he winked. Or perhaps it was a tic, as it was almost indiscernible and he was clearly agitated. His cool blue eyes looking more through me than at me, he explained how he “still needed those SOBs after all to get it back to my yard.”

Turns out the part still had to be authorized by an approved service provider, which would allow the computer to recognize the part. No recognize, no go. Jeb shelled out $230 plus $130 per hour to get someone from the nearest implement dealership, fifty miles away, to, as he put it, “plug in a computer and hit the ‘authorize’ button.”

That’s not the worst of it. The most important input of all in agriculture is time. More than money, these repairs cost farmers their least renewable resource—the one thing they can’t grow, any more than they can borrow it from a bank. Jeb again: “Even if I have a legitimate repair, you’ve got to understand farming is all about timing. If rain is coming and I need to get a crop in or out, that means I need to get out there ASAP, to say nothing of the fact that we’re always chasing daylight, especially in the fall, when darkness comes far too early.” Farmers generally are not comfortable placing the success or failure of their enterprise in the hands of someone else, which is what it feels like when they have field work to do but are waiting for the next available technician.

Earlier in this chapter, I mentioned the devilish details of contract farming and Monsanto’s user agreements. Here’s another, this time concerning the contracts John Deere has crafted for farmers who “buy” its equipment. The contracts stipulate that the company cannot be sued in the event that farmers lose money because repair delays prevent them from tending to their crops.

Concerning the legal question of ownership, John Deere made the argument in 2015 to the U.S. Copyright Office that farmers receive “an implied license for the life of the vehicle to operate the vehicle.”3 In some respects, the company was taking a cue from Monsanto’s gene and seed owning playbook, saying farmers were buying a license and not an actual thing. The reason for the memo was that an exemption to the DMCA was being considered and John Deere wished for a continuation of the status quo. Later that year, in October, a decision was made that surprised many. The Librarian of Congress ruled in favor of the exemption, allowing anyone who owned a tractor—or car, truck, or other vehicle—to tinker with its code. (The Librarian of Congress holds a curious position. He or she oversees the operation of the world’s largest library, with a staff that numbers in the thousands and a collection in the millions, in addition to the U.S. Copyright Office, the government office that manages the registration of all copyrighted materials.)

Shortly after the ruling, Forbes published an article titled “DMCA Ruling Ensures You Can’t Be Sued for Hacking Your Car, Your Games, or Your iPhone.”4 Chalk one up for the little guy. Right? No so fast. The matter, I’m afraid, is more complex than that.

Around the time that the exemption was granted, John Deere started requiring farmers to sign a licensing agreement. The agreement sought to undo the actions of the United States’ top librarian by expressly forbidding nearly all personal repairs and modifications to farming equipment, directing owners to dealerships and authorized repair shops. The document is the same one that also prevents farmers from suing for “crop loss, damage to land, damage to machines, lost profits, loss of business or loss of goodwill, loss of use of equipment … arising from the performance or non-performance of any aspect of the software.”5

Not that they really needed to do that.

For one thing, the exemption extends only to the individual who purchased the equipment. Only the owner has the authority to access and fiddle with the tractor’s software. The moment she brings her nonapproved technician to look at it, she crosses a legal line in the sand, and they both become liable for copyright infringement. A grayer area involves the question of what level of tinkering by an owner is allowed under the exemption. According to attorneys knowledgeable on the subject, the exemption allows for only certain repairs, which is why I have been using the term “tinkering.” For example, software platforms connected to operator safety and vehicle emissions, because of the fact that agencies with nothing to do with copyright law oversee their regulation and compliance, cannot be touched. Just ask Volkswagen, which got caught with its hand in that cookie jar. Tampering with software to circumvent emissions regulations got the company slapped with $4.3 billion in fines in 2015.

Through interviews with right-to-repair activists—or hacktivists, as some liked to be called—I also learned about a burgeoning online market for pirated John Deere software from Poland and Ukraine. Examples include John Deere Service Advisor, which allows farmers to recalibrate tractors and diagnose broken parts; John Deere PayLoad files, which allow farmers to customize and fine-tune elements of their equipment from the chassis, engine, and cab; and John Deere Electronic Data Link drivers, which are needed for one’s computer to communicate with the tractor’s hardware.

Jeb admitted to knowing some people who had tried this black market equipment, quickly assuring me that he never did anything that could get him in trouble with John Deere. When he said this, he gave me a wink—and this time it was definitely a wink.

Back to Nebraska’s proposed Fair Repair Act. The exemption also requires renewal every year. The Fair Repair Act would make the exemption permanent. The bill also “requests”—not the strongest legal language—that operating manuals and diagnostic equipment be made available to farmers. It is hard to fix anything if you do not have access to the necessary materials to troubleshoot and eventually pinpoint what is in need of repair.

Near the end of our interview, Jeb took me into his machine shed. We had been talking about the value of diagnostic equipment, and he had mentioned that he wanted to show me something. Walking in, I noticed immediately layered odors drifting in the air: the low smell of cats and hay, coupled with the higher, acrid sting that could only have been fertilizer, and, sandwiched between, the cool scent of fall air blowing in through the oversized door. Standing there, taking in the enormity of the space, I watched Jeb walk over to a workbench. He grabbed a small device that looked like a stud finder. “Today’s tractors”—he tipped his head in the direction of the John Deere 6210R resting ten yards to my right—“aren’t really any more difficult to fix than the ones I grew up fixing when I was a kid in the 1970s.” Holding the code reader at chest level, he told me, “Until software and diagnostic equipment are available, and until people can put that equipment to work on their smart tractors, farmers will continue to be under the thumb of large implement firms.”

Jeb and others presented me with a scenario that usually came up in discussions of how corporations aggressively assert their property rights over those of farmers. As Jeb put the question, “What would happen if John Deere suddenly decided to stop servicing its equipment?” I doubt strongly that this will ever happen. But it raises an important point, namely, that until farmers have true ownership of their farm equipment, they cannot even learn how to make those repairs. Which makes that scenario a scary one, no matter how unlikely.

Jeb used this memorable analogy when describing the risk: “It’s like relying on someone else to breathe for you; if I couldn’t get my equipment serviced, my business would suffocate to death.”

Here’s to making sure that the status quo does not choke off our nation’s farmers.

As I stepped through the restaurant’s door, the sounds and smells hit me all at once. The espresso machine was whizzing and whining, cutting through the steady murmur of about a dozen conversations, which inexplicably seemed to crescendo whenever I spoke with the waitress. The scent of bacon and eggs wafted through the air, as did cologne from the businessman seated in the booth behind me and stale musk from the air vent above my head that grew heavier whenever the air conditioner kicked in. Just your typical morning at Faye’s Place.

My meeting with Faye—the Faye—almost never happened. She was twenty minutes late for the interview. With my coffee and breakfast finished, I began feeling guilty about holding the table. When she came out from her office, she immediately apologized. “I was stuck on the phone with a lender. Trying to get another merchant cash advance. You familiar with those? Argh, I hate making those phone calls!”

In hindsight, I consider myself lucky that she was delayed. My plan had not been to talk with her about merchant cash advances. I did not even know what they were at the time.

Merchant cash advances are advertised, aggressively in some cases, to small businesses as fast cash. Since the recession a decade ago, credit has dried up for all but the largest businesses. Many upstart entrepreneurs would be happy to have access to any cash. That it is fast is an added bonus.

But fast isn’t all it’s cut out to be. The phrase “pulling a fast one” comes to mind when talking to someone on the receiving end of these loans.

The process works something like this. A loan is made to a business owner, taken out as an advance on future sales. The lender then makes automatic deductions from daily credit or debit card sales or by regularly deducting money from the business’s bank account. The loan also comes with a hefty interest rate.

In Faye’s case, she was given an advance of roughly $20,000. Just to get the loan, she was assessed close to $1,000 in processing fees. The lender then deducted more than $400 per day from her business’s sales for seventy days. With fees, Faye paid back slightly less than $30,000, on a loan for $20,000 that lasted a little over two months. That is an effective interest rate in the triple digits.

Faye is also African American. I mention that because credit is even harder to come by for black and Latino business owners. One recent study looked at nine businessmen—three white, three black, and three Hispanic.6 Similar in size, age, and gender, wearing the same outfits and claiming identical education levels and financial profiles, they visited different banks seeking a $60,000 loan to grow identical businesses. And yet, their experiences once inside were very different. Compared with their white counterparts, the minority small-business owners were given less information about loan terms, were asked more questions about their personal finances, and were offered less assistance by loan officers.

Faye again, describing past conversations with neighbors and fellow business owners: “I can tell you that people owning businesses in this neighborhood are targeted—phone calls, mailings, whatever it takes—by these lenders.” Faye’s café is in a minority-majority community—more nonwhites than whites. She continued by comparing these experiences with those described by friends who own businesses “out by the mall,” in an affluent and largely white community. “Most don’t even know what a merchant advance loan is. That’s no coincidence.”

We ended the interview in her office. The pretense was that she wanted to show me a photo of when President Obama had visited her café. But I also got the sense that our conversation had taken a nerve touching turn and that she wanted some privacy, away from our somewhat nosy waitress—she liked to hover. Once we were inside, Faye’s demeanor changed. It soon became clear she was managing her emotions more in the prior public space than I had realized.

“I got into all this because I wanted to be my own boss. Turns out I’m the one being bossed around. I want to do so much—pay my workers a decent wage; make fresh, healthy, inexpensive food for a community that doesn’t have it; donate food to community projects.” Her restaurant is located in a USDA recognized food desert. Faye then reached for a tissue from a box sitting on her desk, folded it, and dabbed the corner of her left eye. Tears.

Looking down at the tissue, now balled up in her hand, she said, “I just wish there were another way, where I could be a small-business owner without all the headache and heartburn, where I’d be able to take actual ownership of my business.”

For all the Fayes in the world: this book recognizes the burdens of ownership, which include the burdens brought on by financing the Jeffersonian ideal.