—Meri Lao, Seduction and the Secret Power of Women: The Lure of Sirens and Mermaids

—Meri Lao, Seduction and the Secret Power of Women: The Lure of Sirens and Mermaids

IN ADDITION TO THEIR FISHY TAILS and human torsos, the traits and behaviors of mermaids are similar in the various mythologies of the world. These attributes became more homogenized during the middle of the second millennium C.E., as trade routes expanded and seamen journeyed far and wide, sharing their “fish stories” with peoples of various lands. Later, immigrants and slaves brought their mermaid legends with them when they relocated, and those tales merged with the folklore that already existed in their new homes.

However, certain common mermaid characteristics figured prominently in the mythology of diverse cultures, long before the periods of travel and exploration in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Chief among these are mermaids’ enchanting voices, their sensuality, and their destructive potential—all of which lie at the core of the mermaid mystique.

The Mermaid’s Song

“[T]he secret of the power in their song: it is the sound of the subversive, luring us from the orderly conscious world down to the depth of the world of dreams, and the harder we try to ignore that singing, the more we desperately want to hear it.”

—Meri Lao, Seduction and the Secret Power of Women: The Lure of Sirens and Mermaids

—Meri Lao, Seduction and the Secret Power of Women: The Lure of Sirens and Mermaids

According to nearly all legends and stories, a mermaid’s voice isn’t merely melodious enough to rival the greatest of operatic divas. It’s so mesmerizing that men who hear it go wild with delight and jump from their boats or rush into the sea—and subsequently drown. Some sailors, captivated and disoriented by the mermaids’ hauntingly beautiful singing, run their ships aground on rocky shores and, in a state of delicious delirium, they go to their watery graves.

Interestingly, among the numerous reports given throughout the ages by people who claim to have seen mermaids, few mention hearing the infamous singing. Perhaps if they had heard the mermaids’ songs, they might not have lived to tell the tales!

“In stories, poems and myths, hearing a mermaid’s song was considered a haunting and hazardous experience. Typically, it lured the listener to toss aside safety and sometimes his or her whole, known world, and plunge into the waves. Such a leap could bring doom or it could bring salvation. Sometimes it brought both. The mermaid’s song inevitably calls us to the unknown, to the impassioned world of change and possibility. Ultimately mermaids persist in the imagination because they represent a primal human need: to dive deep into the mystery of our un-lived life.”

—Sue Monk Kidd, bestselling author of The Mermaid Chair and The Secret Life of Bees

MAPPING MERMAIDS

As early sailors ventured farther out to sea, mapmakers began picturing mermaids and other marine oddities on maps. Mermaids may have been intended as symbols of the sea itself, or as alerts to seafarers of the mysteries they might encounter on their voyages. Mermaids frequently appear on medieval mappa mundi, such as the thirteenth-century rendering signed by Richard de Haldingham e de Lafford and now housed in Britain’s Hereford Cathedral.

Literary Accounts of Mermaids’ Songs

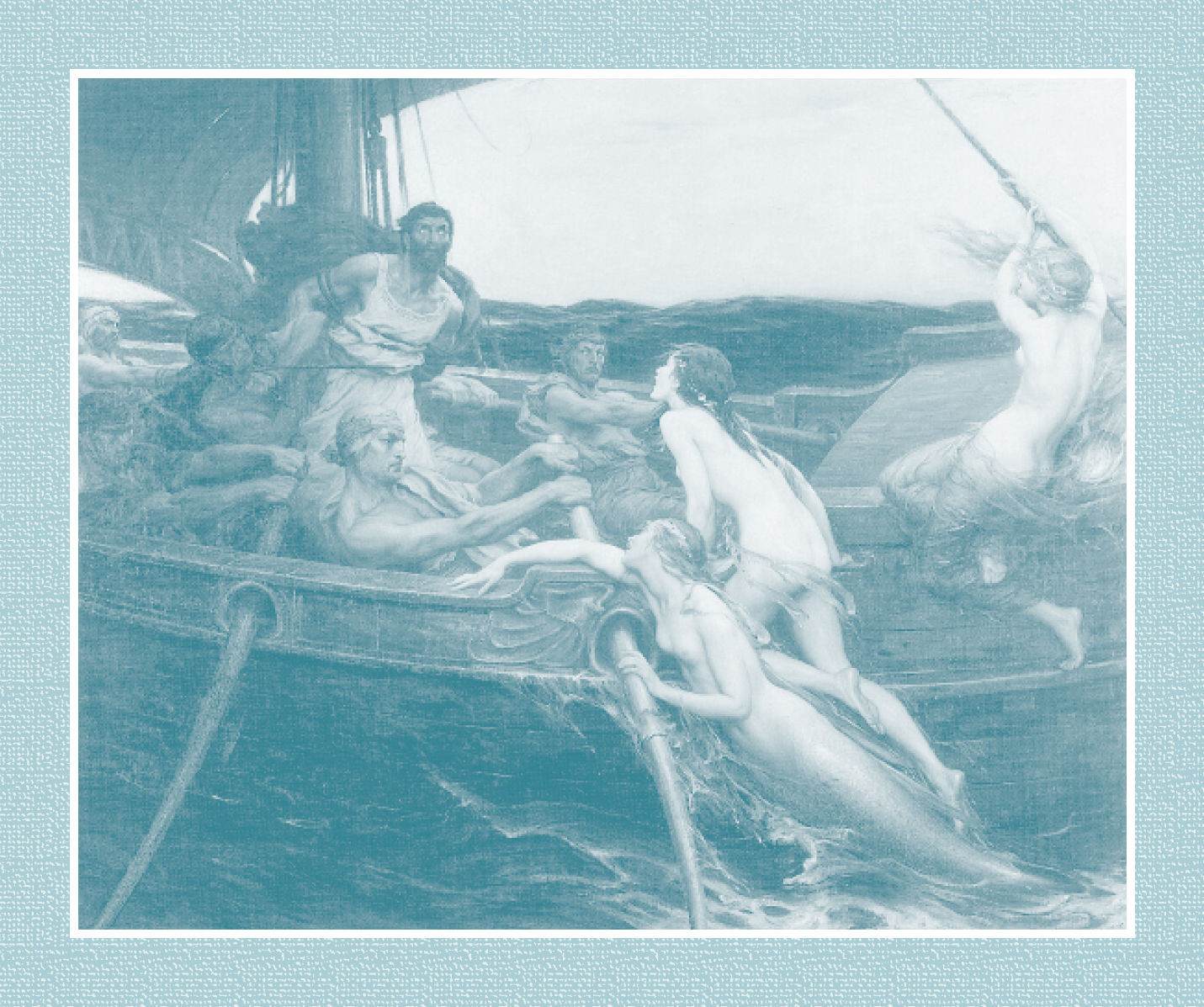

The ancient One Thousand and One Nights says that mermaids’ songs rendered sailors helpless and lured them to their doom. The infamous Sirens of ancient Greek myth are presented as melodious but malevolent temptresses—no man could resist their tantalizing singing. In the 3,000-year-old Odyssey, Odysseus (or Ulysses in Latin) is warned about the Sirens’ powers; he therefore ties himself to his ship’s mast and his sailors put wax in their ears so they won’t be driven mad by the enchantresses’ songs. Our modern-day word “siren,” rooted in the Greek myths of the Sirens of old, has the connotation of a seductive and potentially dangerous human femme fatale.

Folklore remains pretty quiet on the subject of mermen’s singing ability. Some sources report the males as having “silvery” or “fluted” voices, though nothing as exquisite as those of the females. One Cornish legend tells of a handsome young man from the town of Zennor who goes to live with the mermaids—yet people in the town still say they hear his beautiful tenor voice wafting on the waves. But just because mermen don’t possess the bewitchingly beautiful voices of the females of the species doesn’t mean that they lack musical talent. The Scandinavian Havman is said to be an accomplished violinist who enchants women with his skillful playing, and the Greek’s Triton blew a conch shell like a trumpet.

HERBERT JAMES DRAPER, ULYSSES AND THE SIRENS

Deadly Beauties

“[B]ehind this seductive image of the Siren lurks the a metaphor of death, for enticed by her promise and allure, generations have been lured to their certain doom in a thousand different stories that form the basis of powerful and enduring myths and legends that continue today.”

—Beatrice Phillpotts, Mermaids

—Beatrice Phillpotts, Mermaids

Do mermaids intend to sing mariners into “the big sleep”? Or do their victims simply overreact when they hear the otherworldly beauty of the music? It’s a subject for debate. It’s been speculated that sailors, upon observing mermaids floating in the waves, think they see drowning women and jump overboard to rescue them—but in the process the well-meaning seamen drown instead.

Some stories say that mermaids drag men they fancy down into the depths and accidentally drown them, not realizing that humans can’t breathe underwater. Other tales say humans who’ve been drawn into the mermaids’ underwater realms remain there, transformed into merfolk themselves.

Hans Christian Andersen’s popular fairy tale “The Little Mermaid” offers yet another perspective. In it the author explains that the mermaid’s song is a compassionate attempt to calm the fears of sailors who are about to drown in a storm at sea. “They had more beautiful voices than any human being could have; and before the approach of a storm, and when they expected a ship would be lost, they swam before the vessel, and sang sweetly of the delights to be found in the depths of the sea, and begging the sailors not to fear if they sank to the bottom.”

“A mermaid found a swimming lad,

Picked him for her own,

Pressed her body to his body,

Laughed; and plunging down

Forgot in cruel happiness

That even lovers drown.”

—William Butler Yeats, “A Man Young and Old”

MILITARY MERFOLK

Mermaids may be dangerous, but they don’t normally attack people—they use their feminine wiles to lure men to their deaths. Mermen, however, can be more warlike. They’re said to fashion weapons from the body parts of other sea creatures—coral, shells, bones, and the teeth of large aquatic predators.

The Tempest

Many legends link mermaids with storms and even blame them for whipping up tempests at sea in order to sink ships. Some old English stories portrayed mermaids as evil omens and portents of bad luck. It’s said that if a sailor spotted a mermaid, it meant bad weather was coming and he’d never return home again.

Another belief, explained in the twelfth-century text known as the Speculum Regale or The King’s Mirror, states that when seafarers saw a mermaid at the onset of a storm, she served as an oracle and her actions let them know if they’d survive or perish. According to this theory, the mermaid dives underwater and brings up a fish. If she plays with the fish or throws it at the boat, death is imminent. If she eats the fish or tosses it back into the water, away from the ship, the sailors will make it through the tempest alive.

Ominous depictions of mermaids were encouraged by the Catholic Church during the Middle Ages. Medieval church fathers linked mermaids with the deadly sins of vanity and lust, as well as the alluring powers of women in general. Some churches displayed images of mermaids swimming with fish or starfish (which symbolized Christians) as warnings against sexual temptations. If a mermaid held a fish in her hands, it signified that a Christian had succumbed to the sin of lust.

“Thou rememberest

Since once I sat upon a promontory,

And heard a mermaid on a Dolphin’s back

Uttering such dulcet and harmonious breath,

That the rude sea grew civil at her song;

And certain stars shot madly from their spheres,

To hear the sea-maid’s music.”

—William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

“Slow sail’d the weary mariners and saw,

Betwixt the green brink and the running foam,

Sweet faces, rounded arms, and bosoms prest

To little harps of gold; and while they mused

Whispering to each other half in fear,

Shrill music reach’d them on the middle sea.”

—Lord Alfred Tennyson, “The Sea-Fairies”

Bearers of Good Fortune

Not all legends portray mermaids as dangerous. The African water deities known as Mami Wata, who often appear as mermaids, are said to heal the sick and bring good fortune. In Caribbean tradition, the water spirit/mermaid Lasirèn guides people (usually women) underwater where she confers special powers on them. Some European folklore acknowledges their potential dangers, but reminds us that mermaids, like the sea itself, can bring good things to humanity as well as bad.

Mermaids, it seems, are as changeable as the sea—serene one moment and tumultuous the next. The Physiologus or Bestiary (originally written in Greek, probably in the third or fourth century C.E.), was one of the most popular books during the Middle Ages. It characterized a mermaid as “a beast of the sea wonderfully shapen as a maid from the navel upward and a fish from the navel downward, and this beast is glad and merry in tempest, and sad and heavy in fair weather.”

Psychologically, mermaids have been said to represent the complexity of women’s emotions, ranging from playful to stormy, as well as the light and dark sides of the human psyche. Like the fairy, whom movies and children’s stories have also trivialized, mermaids can be both alluring and dangerous—certainly not something to trifle with!

MERMAID FIGUREHEADS

Throughout the centuries, sailors affixed figureheads of mermaids to the bows of their ships to ensure safe and prosperous voyages. Between about 1790 and 1825, the golden era of the clipper ships, beautifully crafted figureheads adorned British and American merchant vessels and warships alike.

Luxurious Locks

You’ll never see a picture of a mermaid with a pixie or brush cut. One of her defining attributes is her long, flowing hair. Seafarers often report seeing a mermaid’s sinuous tresses floating on the waves or twining around her body like seaweed. In some cases, artists (such as those who “cleaned up” the Starbucks logo) depict her modestly covering her breasts with her luxurious locks—something unabashed mermaids wouldn’t even think of doing.

As far as the color of merfolk hair is concerned, green seems to be popular. The ancient Greek Tritons supposedly sported green hair, and legends of merfolk from Ireland and the British Isles also mention their green hair. And tales from Down Under say that the local water spirits known as yawkyawks have long hair that looks like seaweed or green algae.

In Scandinavia, however, where human blondes predominate, so do stories of golden-haired mermaids. Other folktales and sightings report that mermaids’ hair can vary from palest blonde to black—and everything in between, especially the colors that remind us of the sea: green, blue, turquoise, purple, white, and silver.

Siren Sightings

In 1614, American explorer John Smith (best known for his association with Pocahontas) stated he’d seen a mermaid off the coast of Massachusetts. He described her as having long green hair and said she was “by no means unattractive.”

Combs and Mirrors

If you believe what you read in mermaid myths, these lovely ladies devote a lot of time to personal grooming—specifically, combing their hair. Although they may appear devoid of other possessions—even clothing—mermaids throughout the world carry their combs and mirrors with them when they set out to entice human seafarers into their watery worlds. Countless stories speak of mermaids sitting on rocks near the ocean with their glistening tails curled about them, while they comb their long, flowing tresses and examine themselves in hand-held mirrors.

Mythology and art present numerous links between mermaids and Venus/Aphrodite, the Roman/Greek (respectively) goddess of love and beauty. Botticelli’s famous painting The Birth of Venus depicts the goddess with abundant auburn hair, long enough to discreetly conceal her “lady parts.” So perhaps it’s no surprise that we see mermaids gazing into their mirrors and combing their lustrous, flowing locks—just as human women are known to do.

If you’re familiar with astrology or astronomy you may notice the similarity between the mermaid’s hand-held mirror and the glyph for the planet Venus (named for the Roman goddess). It’s probably no accident. Take a look at that symbol—it’s a circle above a plus sign—which suggests that mermaids descended from this ancient goddess of beauty and love.

THE SIN OF INDULGENCE

During the Middle Ages, the comb and mirror—two of the mermaid’s most prized possessions—represented pride and vanity. British medieval churches used these symbols to caution parishioners against indulging in these sins.

Seductive Attributes

“Hair, because of its ability to re-grow, relates to re-birth . . . Hair that was put up or covered with a cap could, metaphorically, be seen as lost—along with any power it was believed to possess. Hair, then, is associated with vital female forces.”

—Patricia Radford, “Lusty Ladies: Mermaids in the Medieval Irish Church”

—Patricia Radford, “Lusty Ladies: Mermaids in the Medieval Irish Church”

A woman’s hair has long been counted among her most seductive attributes. Her hair was considered so enticing, in fact, that until the latter part of the twentieth century Catholic women covered their hair when they attended Mass, lest they distract men with their feminine charms. Until recently, Catholic nuns shaved their hair and veiled their heads. Buddhist nuns, too, shave their heads. Traditionally, Orthodox Jewish women wore wigs or otherwise concealed their natural hair in public. In Islamic culture today, women shroud their heads to signify modesty. So do women in Amish, Mennonite, and other conservative communities.

Obviously, there’s more to a mermaid’s hair than meets the eye. Barbara Walker, author of The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects, proposes that when a mermaid combs her hair she’s performing a type of magic. Because hair traditionally represents strength, the mermaid’s act of attending to her long, lustrous hair signifies her efforts to nurture and enhance her personal power.

The image of the mermaid combing her hair can also be linked to a purification ritual practiced in the Irish church, explains Patricia Radford in “Lusty Ladies: Mermaids in the Medieval Irish Church.” Priests groomed their own hair with special liturgical combs in a rite intended to cleanse both body and soul. Thus, the mermaid’s behavior could symbolize not only physical indulgence but transcendence as well.

WHAT’S SEXY ABOUT THE MERMAID’S COMB?

For anyone who knows Greek, a mermaid’s comb is more than an implement with which to groom her long, luscious hair—it has underlying sexual implications as well. In the Greek language, the words for comb—kteis and pectin—also mean “vulva.”