10

The Drifter

The Lincoln County War should have ended in Alexander McSween’s backyard on the night of July 19, 1878. The war was a struggle to decide whether an existing monopoly or an aspiring monopoly would dominate Lincoln County. Neither would achieve that distinction, for both collapsed in the rubble of war. McSween’s death and Dolan’s bankruptcy left nothing to fight about.

Although now lacking a purpose, the Regulators did not disband. The dozen “iron clads” had shared danger and hardship for five months. The momentum of past rivalries and conflicts kept them together even as their cause crumbled. After the Five-Day Battle, they embarked on a period of uncertain drifting.

For rootless Billy Bonney, the Regulators had furnished the first feeling of belonging since the death of his mother. He not only had been accepted by the older men but had risen to a position of respect and, finally, moderate leadership. Although Doc Scurlock remained captain, his interest increasingly turned to his family and farm. Billy, who had never enjoyed satisfactions such as the Regulators provided, had better reason to want to keep the band together, and more and more he determined the direction of the aimless drifting, if not the ultimate purpose of the drifters.

The first need of the Regulators was horses. Theirs had been left in the Ellis corral on July 19 and had been confiscated by Peppin’s men. “Brown met some fellow and took his saddle and horse,” said George Coe, and over the next few days the others mounted themselves in the same way. Efforts focused on the old Casey ranch below Frank Coe’s place. The Casey boys tied their horses at the front door and ran the ropes inside the house. Billy tried to take one of these. “The horse was snuffy and he failed to get him,” recounted George Coe. “I was a better horseman than the Kid,” he claimed. “He was a fighter but did not understand horses like I did.”

Even so, Billy stole a horse before George, who was the last to remain afoot. Finally, the entire group returned to the Casey ranch to get George a mount. While his friends stood at the ready in the darkness, Coe crept up to a tethered horse. “I had a sharp knife, got hold of the rope, and he never made a move. I got six or eight feet of the rope, whacked it off, throwed a loop over the horse’s nose, jumped on him, hit him with my old hat and left there. The boys commenced shooting, whooping, and laughing.”1

For a few days the Regulators hung around Lincoln, menacing people thought to be friends of Dolan’s. The posse had dissolved, and Peppin, mindful of the fate of Brady, had holed up at Fort Stanton. The Regulators terrorized Saturnino Baca, who more than anyone had prompted Colonel Dudley’s decision to come to Lincoln, and he too sought haven at the fort. They even hurled threats of assassination at Dudley himself, whom they held responsible for McSween’s death.2

Among those who felt endangered was Frederick C. Godfroy, agent for the Mescalero Apaches. In February McSween had tried to get his job for Rob Widenmann (who subsequently, in June, had left Lincoln forever) and had also engineered an official investigation that ultimately got the agent fired. Notwithstanding this background of friction, the animosity of the Regulators is hard to understand, for others had given greater cause for malice. But Godfroy himself, asking Dudley for soldiers to escort him between the fort and the Indian agency, declared that he knew positively that the Kid intended to kill him.3

For this or other reasons, about twenty Regulators showed up at the Indian agency at South Fork on August 5. Frank Coe said that they went to visit Dick Brewer’s grave, though other evidence suggests a plundering foray against the Indian horse herds. Among the band were Bonney, Scurlock, Middleton, Bowdre, Brown, French, and other of the “iron clads,” together with about ten Hispanics, including Fernando Herrera, Ygnacio Gonzalez, and Atanacio Martínez.

As the horsemen approached the agency, the Anglo contingent veered off the road to the left and headed for a spring on the valley floor. The Hispanics continued on the road. No sooner had Billy and his friends dismounted to drink than they heard a burst of firing from the road.

The Hispanics had encountered a party of Indians, and firing had at once broken out. Who fired the first shot or why was never discovered.4 At the agency issue house, Godfroy and his clerk, Morris Bernstein, were doling out rations to some Indian women when they heard the gunfire. Hastily mounting, they galloped out to investigate. Bernstein, in advance, rode into the midst of the battle and was shot down by Atanacio Martínez. With bullets zipping around him, Godfroy turned and raced back to the agency. A few soldiers happened to be there, and they joined Godfroy in a counterattack.

Back at the spring, Billy had dropped the reins of his horse and was drinking. Startled by the firing, the horse reared and bolted. Then both the Indians and the soldiers spotted the men at the spring and opened fire on them. George Coe swung into his saddle and pulled the Kid up behind him, then with the others spurred across the open glade to the timber-screened road. “I’ll bet they shot fifty times at us,” remembered Coe. “We were having to ride on the sides of our horses but they never touched a hair of us.”5

Working their way across the wooded hillside north of the road, the Regulators crept up on the agency corral, which was full of horses and mules. Not only Billy but also three of his comrades had been dismounted, and they doubtless looked on the tempting prize as a fair trade. Opening the gate, they made off with all the agency’s stock. The Kid roped an Indian pony and rode him bareback all the way to Frank Coe’s ranch.6

The killing of Bernstein stirred great excitement and brought public censure on the Regulators. He had been shot four times, his pockets turned out and emptied, and his rifle, pistol, and cartridge belt taken—presumably by his slayers, though Indians could as well have been guilty. Although more accidental than deliberate, the shooting had all the marks of a brutal murder. “This wanton and cowardly affair,” declared Dudley, “excels the killing of Sheriff Brady, inasmuch as the attacking party was ten to one.” Even though he had been drinking at a spring several hundred yards distant, the Kid came to be looked on as Bernstein’s murderer.

The theft of government stock gave Colonel Dudley an excuse to put a detail of troopers on the trail of the culprits. But they easily escaped. Indeed, they vanished from the Lincoln area altogether.

With their stolen stock, Billy and a handful of Regulators turned up on the Pecos River at Bosque Grande on August 13. Bosque Grande had been the first Chisum ranch headquarters, and here they met up with some Chisums. John Chisum had been in St. Louis for several weeks, but his brothers Jim and Pitzer were taking themselves and a big herd of cattle northward out of the war zone.

The meeting may not have been coincidental, for present with the caravan was Sallie Chisum. She and Billy had been exchanging letters, and he may have known about her family’s plan to leave South Spring ranch. Indeed, he wrote her a letter from the McSween house during the siege, and she received it on July 20. On August 13 she recorded in her diary: “The Regulators (Bonney and friends) came to Bosque Grande.”

As the Chisum caravan moved up the Pecos, Bonney and friends went along. When the Chisum caravan laid over at Fort Sumner on August 17, so did Bonney and friends. At both Bosque Grande and Fort Sumner, Billy paid court to Sallie: “Indian tobacco sack presented to me on the 13th of August 1878 by William Bonny [sic].” “Two candi hearts given me by Willie Bonney on the 22nd of August.”7

For Billy and his friends, Fort Sumner offered other attractions as well. Some of the “iron clads” who had tarried around Lincoln after the agency raid joined Billy at Sumner. “When we got there,” recalled Frank Coe, “Kid and others had a baile for us. Got George and I to fiddle. . . . House was full, whiskey free, not a white girl in the house, all Mexican, and all good dancers. . . polite, never say much upon the floor, but start off when the tunes started. Danced all night. Boys swinging them high.”

After a week of fun at Fort Sumner, the Regulators rode up the Pecos River. Laying over two nights at the adobe hamlet of Puerto de Luna, according to Frank Coe, “We had another big dance there. Mexicans sociable there and had respect for white people.” Farther up the valley, they stopped at Anton Chico, “the best of the towns this side of Las Vegas.”8

On the first night at Anton Chico, word came that a posse from Las Vegas, under San Miguel County Sheriff Desiderio Romero, had lined up at the bar of Manuel Sanchez’s saloon inquiring about the “Lincoln County War party” reported to be in town.

“Let’s go down and see what they look like,” said the Kid, “and not have them hunting us all over town.”

Trooping down to the saloon, the Regulators entered and confronted the posse. There were “about eight big burly Mexicans,” recounted Frank Coe, and “of all the guns and pistols you ever saw in your life they had them, as they had come down to take us dead or alive.”

“Always in the lead,” according to Coe, Billy identified the sheriff and asked his business.

When told, Billy replied: “This is the Lincoln County War party I guess you are looking after, right here. What do you want to do about it? Now is the time and you’ll never get us in a better place to settle it than right here.”9

Surveying the Regulator firepower, the sheriff backed down.

“Come up here and take another drink on the house,” said the Kid, “and then we want you to leave town right now.”

The posse gulped the drinks and rode out of Anton Chico. The Regulators stayed about two days longer and had a dance each night.

But a time for decision had come. Several nights after facing down the posse, the group rode about three miles below town, kindled a big bonfire, and had a “war pow-wow.” Frank Coe announced that it was all over, that he and George were pulling out for Colorado.

“It’s not all over with me,” declared Billy. “I’m going to get revenged.” Striding to one side, he said, “Who wants to go with me?”

All but the Coes gathered around him. “We are going the other way,” said George Coe.

At the “war pow-wow” at Anton Chico the Kid emerged as chief of the Regulators. Although signifying the measure of his growth and the esteem of his comrades, it was an empty honor. The war was over and the “iron clads” were verging on dissolution.

Parting with the Coes, Billy and his followers rode toward Lincoln. He intended to steal some horses and drive them over to the Texas Panhandle for sale, he explained.

Billy’s “revenge” fell on Charles Fritz, whose ranch nine miles below Lincoln had provided the setting for the killing of Frank McNab on April 29. Less from sympathy than fear, Fritz followed the lead of Jimmy Dolan. If revenge were the true motive, more fitting targets could have been found. In fact, revenge was more a rationalization than a purpose. On September 7 Regulators fell on Fritz’s horse remuda, grazing on a mesa above his ranch house, and made off with fifteen head.10

Even before Fritz rode into Fort Stanton to complain of his loss, the blustering Colonel Dudley had recorded the return of the “McSween ring.” The Kid, Jim French, Fred Waite, and others, he wrote, had taken over Lincoln. “Stock stealing is a daily matter, the animals being taken toward the Pecos and Seven Rivers.”11

In returning to Lincoln, the Regulators had another purpose besides revenge. Doc Scurlock and Charley Bowdre had remained at home when the others had gone to Fort Sumner after the killing of Bernstein. In war’s aftermath, however, they felt insecure and had decided to leave. Driving the stolen horses, Billy and his friends now helped the Scurlocks and Bowdres move their possessions to Fort Sumner, where Charley and Doc obtained employment with Pete Maxwell. Thus, like the Coes, these two pulled out of the dwindling band of war veterans.12

Others had defected too, and as Billy set forth from Fort Sumner for the Panhandle in late September 1878, he had with him only Tom O’Folliard, Henry Brown, Fred Waite, and John Middleton. Approaching the Texas line, they once more overhauled the Chisum outfit. “Regulators come up with us at Red River Springs on the 25 Sept 1878,” recorded Sallie Chisum in her diary. It was the last time she would ever see Billy Bonney. Considering the uninhibited and free-spirited nature of both, one may guess that the brief romance had achieved a greater intimacy than condoned by the conventions of the time.

The Texas Panhandle, overlaid with the grassy sweep of the Staked Plains, was the last frontier of the cattlemen’s empire. Less than two years before Billy’s arrival, it had been exclusively the domain of Kiowa and Comanche Indians. In the spring of 1877, Charles Goodnight had established his JA-branded longhorns in Palo Duro Canyon, and other outfits had worked down the Canadian River to found such pioneer enterprises as the LX and LIT. Tiny but booming Tascosa served the entire region.13

Billy Bonney chose his market well. Panhandle stockmen needed horses and did not inquire too closely where they came from. “We knew those horses had been stolen over in New Mexico,” recalled one of Tascosa’s reigning belles, “Frenchie” McCormick, “so we didn’t care.” Of Billy she added: “He was the best natured kid and had the most pleasant smile I most ever saw in a young man.”14

With one Tascosa resident Billy struck up a firm friendship. Henry Hoyt, a young physician adventuring in the West before embarking on a distinguished medical career, socialized regularly with the Kid and his friends. He fell in with Billy because, almost alone of the men who frequented Tascosa, the two did not drink. “Billy was an expert at most Western sports,” he wrote, “with the exception of drinking.” In the other sports—poker and monte, horse racing, target shooting, and the ever popular bailes—they participated vigorously.15

Pedro Romero’s weekly bailes proved especially merry, although Romero required everyone to leave his firearms outside. One evening Hoyt and the Kid stepped outside for a stroll. At the far edge of the plaza Hoyt challenged Billy to a footrace back to the dance hall. Tearing across the plaza, Billy failed to check his pace as he neared the doorway. He tripped on the threshold and sprawled in the middle of the crowded floor. “Quicker than a flash,” said Hoyt, “his prostrate body was surrounded by his four pals, back to back, with a Colt’s forty-five in each hand, cocked and ready for business.” No one knew where the guns had been hidden, but for the Kid and his friends embarrassment turned to disappointment when, having broken the rules, they found themselves barred from Romero bailes.16

Dr. Hoyt portrayed Billy Bonney at this time. He was

a handsome youth with smooth face, wavy brown hair, an athletic and symmetrical figure, and clear blue eyes that could look one through and through. Unless angry, he always seemed to have a pleasant expression with a ready smile. His head was well shaped, his features regular, his nose aquiline, his most noticeable characteristic a slight projection of his two upper front teeth.

“He spoke Spanish like a native,” added Hoyt, “and although only a beardless boy, was nevertheless a natural leader of men.”17

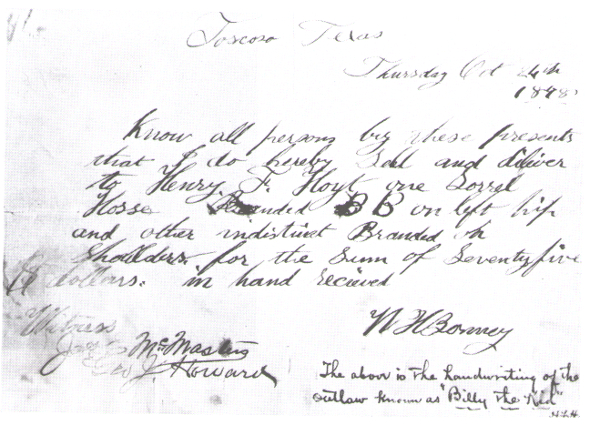

As the time for departure neared, Hoyt presented Billy with a gold watch he had admired, and Billy returned the favor with a sorrel horse that Hoyt had admired. That there be no later question of ownership, Billy stepped to the bar in Howard and McMasters’ store and wrote out a bill of sale. The date, October 24, 1878, marked the approaching end of Billy’s sojourn in the Panhandle.18

Having disposed of their stolen horses, the gang discussed the next move. Middleton, Waite, and Brown wanted to turn their backs on New Mexico, where they felt that constant danger, if not death, awaited them. They urged Billy and Tom to come east with them. But Billy insisted on returning and could not be dissuaded. They ended the argument by going their separate ways, Billy and Tom heading back to Fort Sumner. Thus did the last of the Regulator band disintegrate.19

For the next two months Billy and Tom seem to have been at loose ends. They spent several weeks at Fort Sumner, frequenting the bailes, gambling, and visiting with Doc Scurlock and Charley Bowdre. Then they drifted westward, back to the familiar haunts around Lincoln. Billy had many friends here, and he had once wanted to settle on his own spread nearby. Like thoughts may have drawn him again to Lincoln.

His presence did not long remain unnoticed. By mid-December Colonel Dudley was lamenting the return, “in the last month,” of such “murderers and rustlers” as the Kid and others of the old band of Regulators. On December 20 he issued an order placing Fort Stanton off limits to ten named men and “other parties recognized as the murderers of Roberts, Brady, Tunstall, Bernstein, and Beckwith.”20

Most of the men named in Dudley’s proscription were nowhere near Fort Stanton. French, Scurlock, Bowdre, Brown, and the Coes had fled to safer realms. But “Antrim alias Kid” had come back, with his sidekick Tom O’Folliard, and they promptly got caught up in the old rivalries of the Lincoln County War. As Dudley’s order betrayed, the Lincoln cauldron had started bubbling anew.21

1. Billy the Kid. Of half a dozen or more pictures that may be Billy the Kid, this is the only one that is indisputably Billy the Kid. It is one of two almost identical tintypes taken at the same time at Fort Sumner in 1880. The original of the first disappeared years ago, and most reproductions are indistinct. This is taken from the original of the second, which was preserved for years in the Sam Diedrick family and came to light only in 1986. Since tintypes are reversed images, this picture led to the myth of the left-handed gun. Here the reversed image has been reversed to show the Kid as he actually posed, with a Winchester carbine in his left hand and his holstered Colt single-action on his right hip. (Reproduced by special permission of the Lincoln County Heritage Trust)

2. Main Street in Silver City, New Mexico, in the 1870s. Young Henry Antrim spent two years here, 1873–75, before falling afoul of the law, squirming up the chimney and out of the local jail, and vanishing into Arizona. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

3. Lincoln, New Mexico, scene of Billy’s coming of age in the Lincoln County War. Although taken about 1885, this view portrays the town much as it appeared in 1878. The Dolan store, later the county courthouse, is in the foreground, the Wortley Hotel is hidden in the trees across the street, and the Tunstall store is the building with the pitched roof in the right center. (Museum of New Mexico)

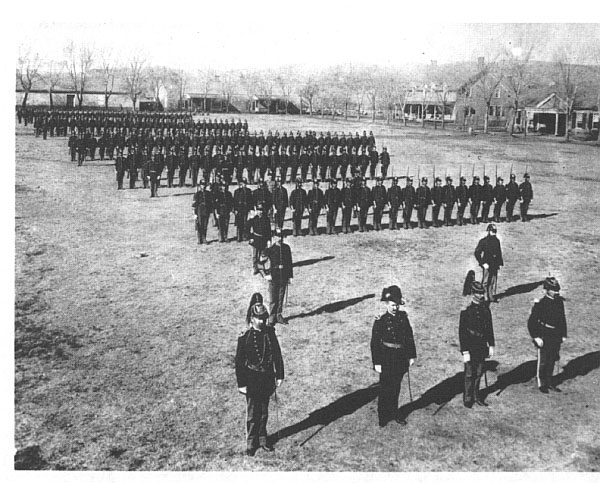

4. The U.S. Army post of Fort Stanton sprawled on the banks of the Rio Bonito nine miles above Lincoln. Although maintained to keep watch on the Mescalero Apache Indians, it played an important role in the Lincoln County War. On July 19, 1878, Colonel Dudley’s Fort Stanton troops intervened decisively in the climactic battle for Lincoln. (National Archives)

5. Frederick T. Waite. A Chickasaw from Indian Territory, Fred Waite was the Kid’s closest friend during the Lincoln County War. The two had planned to take up farming on the Peñasco, but the outbreak of war prevented the partnership. Later, Waite returned to the Indian Territory and led a quiet and useful life. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

6. Charles and Manuela Bowdre. With Doc Scurlock, Charley farmed on the Ruidoso until getting caught up in the Lincoln County War. At Blazer’s Mills he fired the fatal bullet into the groin of Buckshot Roberts. After the war Bowdre rode with the Kid out of Fort Sumner but also tried to break his outlaw ties and lead an honest life. At Stinking Springs, Pat Garrett’s bullet ended Charley’s dilemma. (Museum of New Mexico)

7. Thomas O’Folliard. At sixteen, Tom came up from Texas in time to participate in the final scenes of the Lincoln County War. With the Kid he escaped from the burning McSween house and then became his worshipful sidekick, happy even to hold his horse during nocturnal adventures with eager paramours. Tom died in front of Pat Garrett’s Winchester at Fort Sumner in December 1880. (Museum of New Mexico)

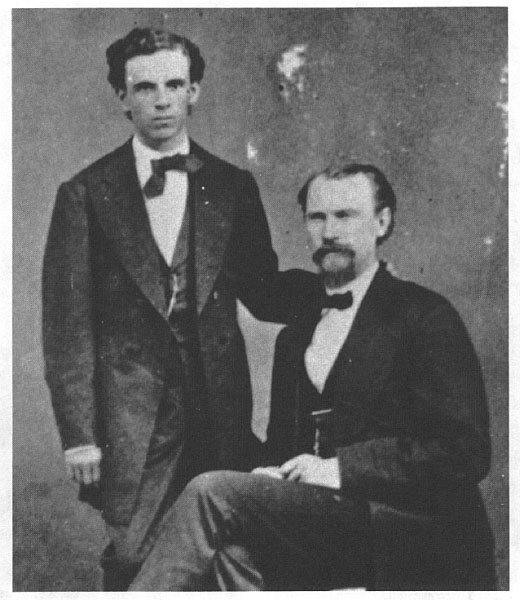

8. John H. Tunstall and Alexander A. McSween. The young Englishman, Tunstall, teamed up with Scotsman McSween, Lincoln’s only lawyer, to challenge the mercantile monopoly imposed on Lincoln County by Lawrence Murphy and his protégés, James J. Dolan and John H. Riley. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

9. Jimmy Dolan stands beside his mentor, Murphy.

Johnny Riley shrank from gunfire but was adept at devious dirty work.

Dolan henchman Jacob B. Mathews led the posse that killed Tunstall. Mathews also shot the Kid in the thigh during the Brady assassination and testified in his murder trial. Understandably, Billy had no love for Mathews. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

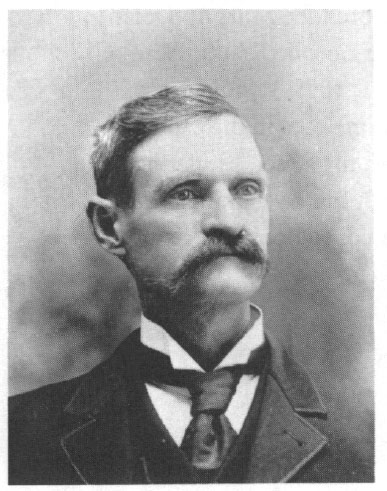

10. A veteran soldier and competent lawman, Sheriff William Brady favored the Murphy-Dolan side in the Lincoln County War. On April 1, 1878, Regulators gunned him down in the center of Lincoln’s only street, escalating the war and ultimately gaining the Kid a murder conviction. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

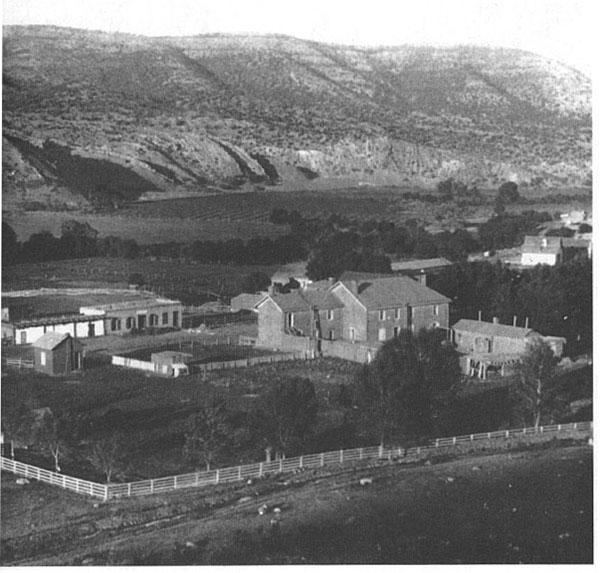

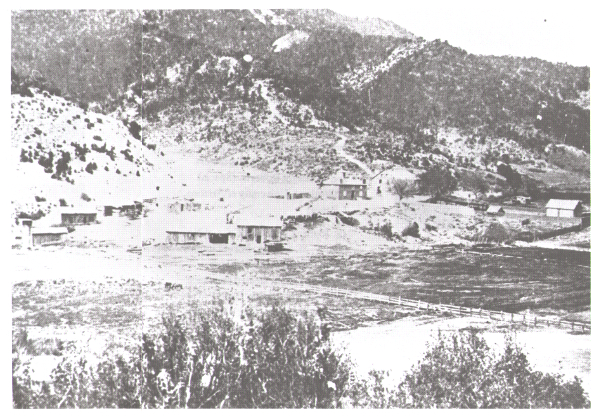

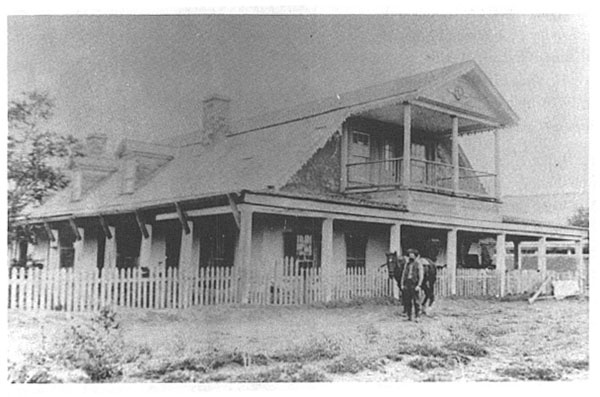

11. Blazer’s Mills, scene of the classic Old West shootout that took the lives of Dick Brewer and Buckshot Roberts. The house in the right center was the focus of the battle. This picture was taken in 1884. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

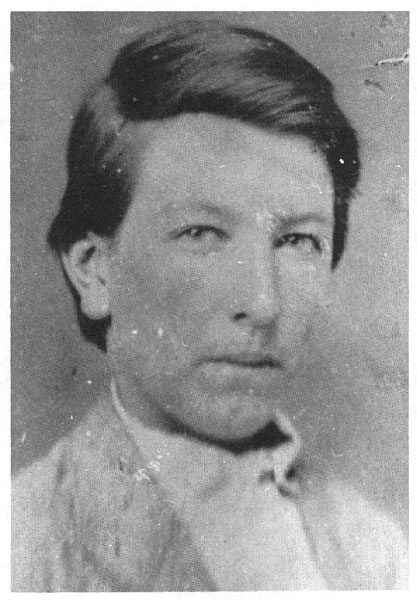

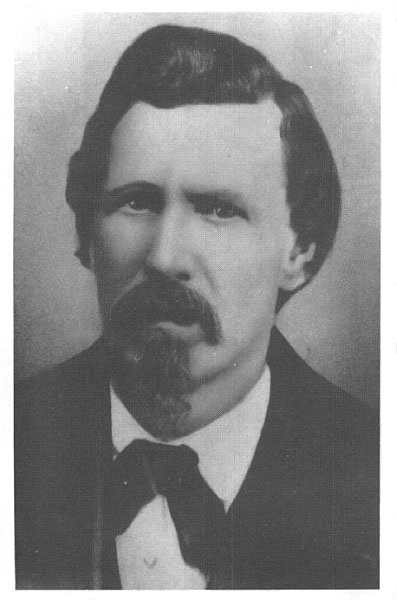

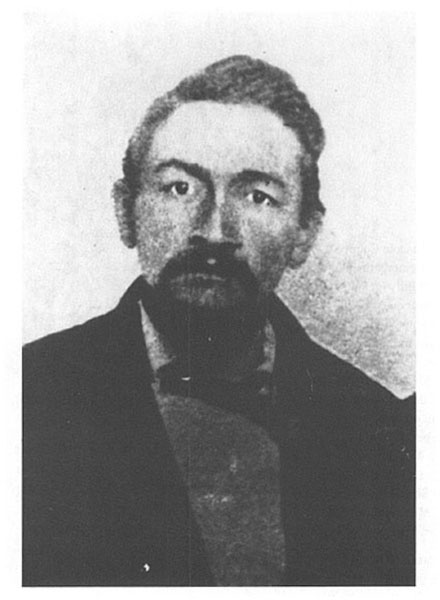

12. Tunstall’s foreman, Richard Brewer, served as first captain of the Regulators, until Buckshot Roberts blew his brains out at Blazer’s Mills. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

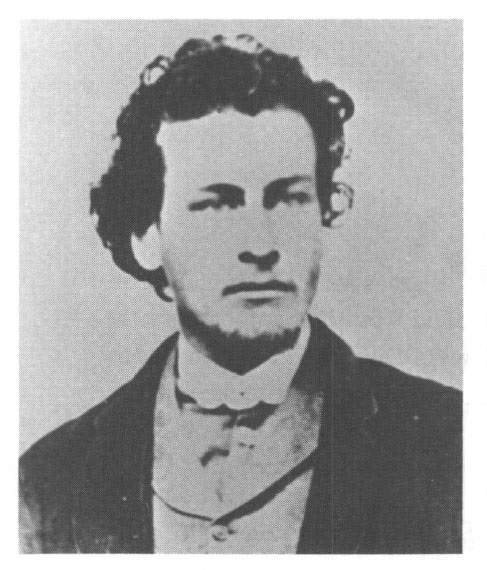

13. Iowa dentist Joseph H. Blazer established a sawmill and gristmill at South Fork at the close of the Civil War. His big house on the Tularosa River provided the battleground for the gunfight between Dick Brewer’s Regulators and Buckshot Roberts. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

14. Lieutenant Colonel Nathan A. M. Dudley, Fort Stanton’s pompous and bombastic commanding officer, steered an erratic course in the Lincoln County War. His appearance in Lincoln on July 19, 1878, led to the defeat of the McSween forces. (Collections of the Massachusetts Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion, U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pa.)

15. Robert Beckwith, son of patriarch Hugh Beckwith of Seven Rivers, led sheriff’s possemen into McSween’s backyard on the night of July 19, 1878, only to fall with a fatal bullet in his left eye. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

16. Governor Lew Wallace, sent to New Mexico to end the Lincoln County War, proved more interested in completing his novel, Ben-Hur. His unfulfilled bargain with the Kid contributed to the boy’s drift toward outlawry. (Museum of New Mexico)

17. Judge Warren Bristol presided over the Third Judicial District Court. Although partial to the Dolan cause in the Lincoln County War, he was easily frightened by the gunmen of both sides. In April 1881 he sentenced the Kid to be hanged for the murder of Sheriff Brady. (Museum of New Mexico)

18. John Simpson Chisum, the “cattle king of New Mexico.” Chisum favored the McSween cause in the Lincoln County War but did not, as the Kid later insisted, promise Billy wages for his service as a McSween gunman. Nonetheless, Billy blamed Chisum for all his troubles. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

19. In the Texas Panhandle in the autumn of 1878 the Kid formed a close friendship with Dr. Henry Hoyt, later to pursue a distinguished medical career. This bill of sale, in the Kid’s handwriting, legalized his gift to Hoyt of a sorrel horse. (Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, Canyon, Texas)

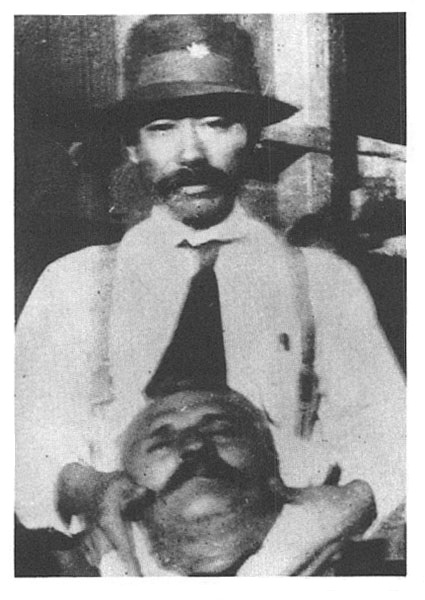

20. One of Billy’s outlaw associates was Dave Rudabaugh, shown here in 1886 after citizens of Parral, Mexico, separated his head from the rest of his body. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

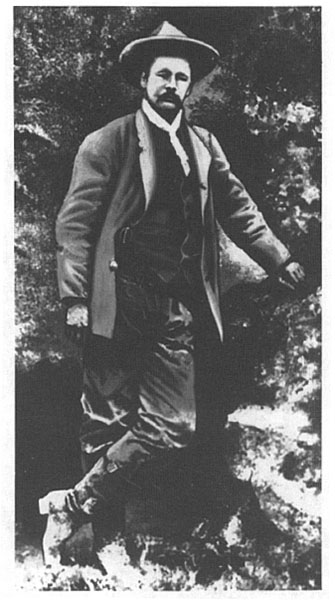

21. A big, muscular bully, Bob Olinger fought against the McSween forces in the Lincoln County War. As a deputy sheriff, he died when Billy the Kid, escaping from confinement, blasted him in the face and chest with his own shotgun. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)

22. The Kid became acquainted with Godfrey Gauss when the fatherly old German was cook at the Tunstall ranch. On April 28, 1881, Gauss was in the courthouse yard in Lincoln and helped Billy make good his escape. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

23. Lincoln County Courthouse, formerly the Dolan store, scene of Billy the Kid’s spectacular breakout on April 28, 1881. Bob Olinger entered the gate to the left of the balcony and was shot by the Kid from the upstairs side window. Later, Billy harangued townspeople from the balcony in front, then rode out of town. In February 1878, at the outbreak of the Lincoln County War, Billy and Fred Waite were held here for almost two days by Sheriff Brady and his possemen. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

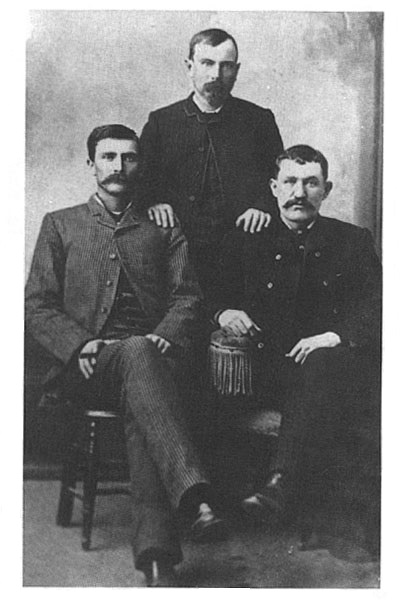

24. Pat Garrett and John William Poe (seated) pose with a later deputy, Jim Brent. On July 14, 1881, Garrett and Poe, with Tip McKinney, ended the outlaw career of Billy the Kid.

The shooting took place in the Maxwell house at old Fort Sumner. Garrett was in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom, the corner room in the foreground, when the Kid entered and was gunned down. (Mullin Collection, Haley History Center)

25. Marshall Ashmun Upson. A wandering journalist who became acquainted with the Kid while serving as Roswell postmaster, Ash Upson ghosted Pat Garrett’s Authentic Life of Billy the Kid and thus contributed enormously to the legend that bloomed after Garrett killed Billy. (Special Collections, University of Arizona Library)