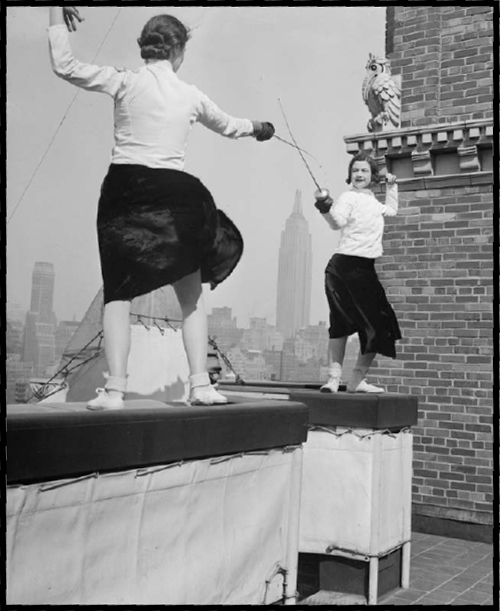

Two members of the New York University Women’s Fencing Team practice for the Intercollegiate Women’s Fencing Championships in 1933.

Two members of the New York University Women’s Fencing Team practice for the Intercollegiate Women’s Fencing Championships in 1933.

And so Miss G——died, not because she had mastered the wasps of Aristophanes . . . not because she made the acquaintance of Kant . . . , and ventured to explore the anatomy of flowers and the secrets of chemistry, but because, while pursuing these studies, while doing all this work, she steadily ignored her woman’s make. Believing that woman can do what man can, for she held that faith, she strove with noble but ignorant bravery to compass man’s intellectual attainment in a man’s way, and died in the effort.

EDWARD H. CLARKE, M.D., SEX IN EDUCATION, OR, A FAIR CHANCE FOR THE GIRLS (1873)

One long-standing argument against the education of women had to do with the supposed “delicacy” of their constitutions. Unlike her brother, the girl child required special treatment, without which she was subject to dire physical consequences. In the mid-nineteenth century, a properly raised daughter was

guarded from over fatigue, subject to restrictions with regard to cold, and heat, and hours of study, seldom trusted away from home, allowed only a small share of responsibility;—not willingly, with any wish to thwart her inclinations—but simply because, if she is not thus guarded, if she is allowed to run the risks, which, to the boy, are a matter of indifference, she will probably develop some disease, which, if not fatal, will, at any rate, be an injury to her for life . . .1

A girl was particularly susceptible to such life-or fertility-threatening injuries because of the nature of her reproductive system in particular and the way in which nineteenth-century medicine viewed the human body in general. According to contemporary wisdom, menstruation was particularly stressful on the female body. Mental stimulation—studying, for example—during the menstrual period drew a woman’s bodily energies away from her uterus with what many medical writers assured readers were dreadful and long-lasting consequences. The danger was especially great during puberty, when a girl’s system hadn’t yet grown accustomed to the monthly flow. The weeks and months prior to menarche, and thereafter until regular menstruation was established, were of particular importance. Unless the development of the female reproductive system was accomplished during puberty, it was “never perfectly accomplished afterwards.”2 Healthful menstruation was important to a girl’s future “happiness in marriage, easy child-beds, and the constitution of children.” Neglecting menstrual health therefore violated “a duty owed to others as well as herself.” Not coincidentally, this crucial developmental phase (roughly from age twelve though twenty, according to nineteenth-century medical men) overlapped the time young women were most likely to enter college.3

Education also caused health problems in younger girls, even those who never went on to college. George Napheys, M.D. (1842–1876), a popular medical writer whose The Physical Life of Woman went into many editions after its 1869 debut, marked boarding-school life as one of the “fertile sources” of menstrual disturbances in adolescent girls. No one rated the education of the mind higher than himself, he told readers, but he did not “hesitate a moment to urge that if perturbations of the [menstrual] functions become at all marked in a girl at school, she should be taken away.” It was better for her to live in idleness for a year than to “become a dead-weight, through constant ill-health, on her husband in after life.”4 “Overwork at school” was also a cause of chlorosis, popularly known as “green sickness,” a generalized anemic condition involving lethargy, lack of appetite, vague pains, bad temper, and “depraved tastes—such as a desire to eat slate-pencil dust, chalk or clay,” as well as its titular symptom, a greenish tinge to the complexion.5

The “Sex in Education” Controversy

The link between education and female ill health was widespread in popular medical literature, but the book that brought the argument to the forefront of American discourse was Dr. Edward H. Clarke’s Sex in Education, or, A Fair Chance for the Girls (1873). Clarke was a retired Harvard medical professor who, he emphasized, was not against the education of girls, merely against educating them in the same manner as boys, whether at coeducational campuses or at woman’s colleges.

A “fair chance” in education for girls meant observing the laws of “periodicity”: every four weeks, between the ages of fourteen and eighteen (perhaps even until the age of twenty-five), girls needed to take a break, in part or in whole, from both study and exercise, thus giving “Nature an opportunity to accomplish her special periodical task.” This monthly diminution or cessation of study was a “physiological necessity for all, however robust” their appearance.6 Girls who ignored their reproductive organs in favor of study “graduated from school or college excellent scholars, but with undeveloped ovaries. Later they married, and were sterile” or suffered from a variety of ailments, including “neuralgia, uterine disease, hysteria and other derangements of the nervous system.”7

Of all the arguments Clarke made in Sex in Education, perhaps the most damaging by virtue of its sheer staying power was that study made women masculine. The “arrested development” of the reproductive system that resulted from study during the menses led to a corresponding change in intellect and psyche, “a dropping out of maternal instincts, and an appearance of Amazonian coarseness.” Clarke’s assessment of these masculinized women was as brutal as it was blunt: they were “analogous to the sexless class of termites” or “the eunuchs of Oriental civilization.”8

Clarke devoted an entire chapter to horror stories of top students whose health collapsed from the combination of overstudy and uterine neglect. Miss D——attended Vassar from the age of fourteen, and “studied, recited, stood at the blackboard, walked, and went through her gymnastic exercises, from the beginning to the end of the term, just as boys do.” One day, she fainted while exercising. This happened again and again, until she was compelled to “renounce” physical education altogether. During her junior year, she began to suffer monthly pain and a lessening “excretion” of menstrual blood. Friends and faculty suspected nothing from her apparently healthy appearance. She graduated “with fair honors and a poor physique,” and began an inexorable slide into “steadily-advancing invalidism.” Clarke diagnosed “an arrest of the development of the reproductive apparatus,” confirmed by his examination of Miss D——’s bosom, “where the milliner had supplied the organs Nature should have grown.”9 (Imagine how this particular slander would have played a century or so later, when America’s bosom fixation was firmly in place. Tying collegiate education to A-cup status would have drained the campuses of all but the most resigned academic martyrs.)

Miss E——was the daughter of a well-known scholar and “one of our most accomplished American women.” She, too, “studied, recited, walked, worked, stood . . . in the steady and sustained way” of male students. She seemed healthy until, “without any apparent cause,” she ceased menstruating. An “inveterate acne” appeared, followed by “vagaries and forebodings and despondent feelings,” insomnia, and loss of appetite. “Appropriate treatment faithfully persevered in was unsuccessful in recovering the lost function,” and Clarke was “finally obliged to consign her to an asylum.”10

Perhaps most disturbing was the example of Miss G——, who graduated at the head of her class at an unnamed coeducational western college. Although she was robust throughout her collegiate career, the damage was nonetheless done. After graduation, her health failed, eventually leading to her death some years later. A postmortem revealed degeneration of the brain. It was “an instance of death from over-work” combined with carelessness where her femininity was concerned.

Tragic though Miss G——’s untimely demise was, it may have been preferable to the ends met by other broken-down scholars, as dutifully reported by Clarke. Miss A——, for example, became hopelessly and violently insane after her marriage, whereas Miss C——was hospitalized with hysteria and depression. Miss F——, long the victim of hypochondria and insomnia, was just returning to health under Clarke’s “careful and systematic regimen” when she was killed by a sudden accident.11

Packed with such sensational tidbits, it’s not surprising that Sex in Education was an immediate best-seller. In a preface to the second edition, the author himself modestly pointed out that the new printing followed “little more than a week after the publication of the first.”12 A bookseller in Ann Arbor, Michigan, reported selling two hundred copies in a single day.13 A flood of journal articles and at least four books replying to Dr. Clarke followed—most impressive when one remembers there were no morning talk shows, no Internet discussion groups, no electronic media whatsoever to whip the waves of controversy. The answering volumes were mostly penned by women, and as a contemporary reviewer wryly observed, “the ladies, it is needless to say are ‘down’ on the Doctor with more or less temper, according to knowledge and position.”14

Eliza Bisbee Duffey’s “temper,” as recorded in her No Sex in Education; or, An Equal Chance for Both Girls and Boys (1874), still echoes tartly down the years:

If there is really a radical mental difference in men and women founded upon sex, you cannot educate them alike, however much you try. If women cannot study unremittingly, why then they will not, and you cannot make them. But because they do, because they choose to do so, because they will do so in spite of you, should be accepted as evidence that they can, and, all other things being equal, can with impunity.15

Instead of Clarke’s stunted, small-bosomed victims of physical collapse, argued Duffey, education created “women with broad chests, large limbs and full veins, perfect muscular and digestive systems and harmonious sexual organs,” who could keep pace with men either in a foot race or intellect to intellect.16

In 1943, a group of Oklahoma State coeds showed health, vitality, and just how wrong Clarke’s Sex in Education turned out to be.

Mrs. Julia Ward Howe scoffed at Clarke’s contention that “you cannot feed a woman’s brain without starving her body.”17 The venerable poet, novelist, women’s rights advocate, and clubwoman gathered essays refuting Clarke in Sex and Education: A Reply to Dr. E. H. Clarke’s “Sex in Education” (1874). Howe and others questioned the quality of Clarke’s research—particularly the statistically small number of supporting cases he presented—while reports from far-flung coed campuses such as Antioch, Oberlin, and the University of Michigan confirmed the health and vitality of both female students and alumnae.

The argument even wound its way into An American Girl and Her Four Years in a Boys’ College (1878). Will Elliott and her sister coeds at Ortonville react to Clarke’s work with “disgust and amusement.”18

Caught up in the hubbub surrounding the book, Will wonders “what the dear old humbug has to say against girls.” After reading Sex in Education, she astutely notes the recent origin of the “precious” doctor’s concern:

Women have washed and baked, scrubbed, cried and prayed themselves into their graves for thousands of years, and no person has written a book advising them not to work too hard; but just as soon as women are beginning to have a show in education, up starts your erudite doctor with his learned nonsense, embellished with scarecrow stories, trying to prove that woman’s complicated physical mechanism can’t stand any mental strain.19

Will was on to something here, not only that lower-class women had worked for centuries without alarm being raised as to their physical health, but also the question of Clarke’s own motives. In Sex in Education, Clarke declared that his alma mater and former employer, Harvard, was a “red flag” target that “the bulls of female reform” were “just now pitching into.” Answering those who would open up his beloved Harvard to coeducation, Clarke argued that, even despite its “supposed” riches, the expense to fit Harvard to meet the “special and appropriate” needs of women students was one the school “could not undertake” without an additional million or two dollars.20 Or so he said.

Clarke’s arguments disturbed faculties as well as students. In an 1877 report to the board of regents, a visiting committee to the University of Wisconsin worried about “the fearful expense of ruined health” and decided that it was “better that the future mothers of the state should be robust, hearty, healthy women, than that, by over study, they entail upon their descendents the germs of disease.” No doubt considering the university’s twenty-odd years of healthy female students, President Bascom replied that study was, in fact, “congenial to the habits of young women” and politely noted that “the visiting committee is certainly mistaken.”21

As women entered college in greater and greater numbers, and their prophesized collapse did not occur, arguments linking women’s health and education eventually disappeared. The decline was gradual, however; the 1894 edition of The Physical Life of Woman still made the link between women’s education and ill health, while magazine articles just before the turn of the twentieth century sought to reassure readers—especially parents of daughters—that college girls were as robust and happy as those who stayed at home. Concerns about higher education and ill health lingered well into the twentieth century. Writing in 1911, Dr. William Lee Howard was mostly concerned with the deleterious effects of basketball and other strenuous forms of exercise on youthful reproductive systems, but he also advocated girls staying home from school during the menstrual period. He took his appeal straight to parents:

Which had you rather YOUR daughter should have, a certificate of perfect health, with the knowledge that when she marries she can become a mother without danger to herself and child, that she can remain happy in the nursery instead of miserable in the hospital, or a diploma stating that she can read French poetry and write an essay upon “Woman’s Career”?22

The nervous strain and “ceaseless activity” of college life itself were other threats to health. One writer blamed the resultant “worn nerves and impaired digestion” on the combination of poor eating (all those hard-to-digest pies and doughnuts at midnight spreads), and colleges that didn’t enforce the “ten o’clock” rule but rather allowed girls to sit up all night studying. She also blamed extracurricular activities, whether they were athletic, literary, or benevolent in nature. Few escaped her inclusive list:

basket ball, hockey tennis; the glee club, the mandolin club, the French and German clubs; the literary societies; the fraternities; the work on literary magazines; the little plays so frequently given by societies; the meetings in connection with social settlements and other benevolent or religious associations; the teas and suppers; and, worst of all because the most taxing, the senior dramatics which cap the climax of fatigue.23

Alas, she didn’t explain just what made the senior dramatics so taxing. She did, however, describe how a girl who for two weeks participated in extracurricular activities every night until midnight and then studied until 2:00 A.M. came down with, not the mononucleosis that nearly every modern college student seems to have a brush with, but appendicitis.

Calisthenics for Ladies

Emma Willard, Catharine Beecher, and Mary Lyon all recognized the healthful benefits physical activity conferred on young women and incorporated various exercises into their successful educational programs. Beecher and Lyon in particular used the exercise system known as calisthenics. In 1834, Amherst professor and physical-education advocate Edward Hitchcock defined the term as “the classical name for female gymnastics”; another practitioner noted it derived from “two Greek words signifying beauty and strength.”24 This did not mean the sort of acrobatic tumbling and gravity-defying apparatus work we associate with today’s Olympic-level female gymnasts. As practiced beginning in the early part of the nineteenth century, calisthenics were a synchronized series of movements usually done while rooted to one spot on the floor, either with or without music. Some practitioners advocated the use of the bowling-pin-shaped Indian clubs (so named after British soldiers stationed in colonial India adapted native exercises employing similar devices), beanbags, or other weights for added benefit.25 Most importantly, calisthenics were always “carefully accommodated to the delicate organization of the female sex,” as noted in an 1856 guide.26 Engravings in the same book showed gymnastic exercises for men which involved rope climbing, pole vaulting, and the parallel bars, while women stood in place and gently waved their arms or small wooden dumbbells. Which isn’t to say that calisthenics weren’t rigorous in their own way. Catharine Beecher outlined her suggested routine of fifty exercises in Physiology and Calisthenics for Schools and Families (1856). Students began by beating their chests (to “enlarge the chest and lungs”), then came arm extensions and stretches, followed by deep knee bends, leg raises, and high stepping, among other movements.27 But Beecher also stressed the “simple gracefulness of movement and person” that resulted in girls who practiced calisthenics. When another popular health reformer, Dio Lewis, updated some of Beecher’s exercises, Beecher found the modifications “objectionable”; Lewis’s adaptations were “so vigorous and ungraceful as to be more suitable for boys than for young ladies.”28

William Hammond was a snarky Amherst undergrad when he visited Mount Holyoke in the 1840s. As he recorded in his diary, the sight of students engaged in calisthenics failed to impress him:

Saw some of the young ladies exercise in calisthenics, a species of orthodox dancing in which they perambulate a smooth floor in various figures, with a sort of sliding stage step. . . . The whole movement is accompanied by singing in which noise rather than tune or harmony seems to be the main object. By a species of delusion peculiar to the seminary they imagine that all this [is] very conducive to health, strength, gracefulness, etc.29

Delusional or not, calisthenics were part of a larger mid-nineteenth-century movement toward health reform which appeared just as the American population began to relocate away from the agricultural countryside with its numerous opportunities for healthy outdoor exercise and the consumption of fresh produce and meat, to the industrial city where adulterated foods were the norm and the majority of workers and students were engaged in what was considered dangerously sedentary “brain work.” Combined with questions about the ability of females to remain reproductively sound while engaged in heavy study, it’s not surprising that Matthew Vassar and his associates included a “Calisthenium” in the plan for his women’s college.30

The author of Ladies Home Calisthenics (1890) described woman’s combined obligations of physical fitness and maternity:

The health of coming generations and the future of a nation depend in great part upon the girls. They are to be the coming mothers; and, as such, obligations for the formation of a new race are incumbent upon them. These obligations they can by no means fulfill unless they are sound in mind and body.31

In this regard, the practice of calisthenics was nothing less than patriotic. The exercises helped women build strength for their most important job—reproducing the race, specifically, the white middle and upper classes in the face of increasing non-western-European immigration at the turn of century. And the exercises themselves were deemed “ladylike”—unlike the strenuous, sweaty game of basketball.

Basketball

The game was invented in 1891 by Dr. James Naismith of the YMCA. A year later, it was adopted into the physical educational program at nearby Smith College and quickly became a popular staple of women’s physical education in both women’s and coed colleges. And why not? Basketball was fun. It was fun when we played it, boys and girls together, in our fifth-grade gym period and I made a completely accidental midcourt hook shot that secured both the notice of and later a valentine from Mark Elbach. Imagine for a moment how much fun it must have been for a group of girls in the 1890s. Raised with restrictions of both clothing and behavior, they got the chance to shed both corsets and decorum in an unfettered physical competition that the more sedate practice of calisthenics didn’t offer. Watching girls play basketball “in bloomers and sweaters” in 1898, an observer marveled a bit wistfully at their freedom in dress and movement. “The alumnae of only ten years’ standing were mourning because the college in their day supplied nothing better than boarding-school calisthenics.”32 No wonder the early college girls loved playing basketball so much—it must have been liberating beyond their wildest dreams to run, jump, yell and actually compete. “We played as hard as we could. And loved every moment of it,” recalled one woman of her days on the court in the years leading up to World War I.33

Title IX

The college girls of the 1890s who played “girls’ rules” basketball with such relish would not recognize the lean, muscled competitors who play the game today.

The college girls of the 1890s who played “girls’ rules” basketball with such relish would not recognize the lean, muscled competitors who play the game today.

The exponential growth and development of women’s college basketball and other sports were due to Title IX of the Educational Amendments Act, passed in 1972. Title IX prohibits sex discrimination at any educational institution that receives federal funds. Under its authority, schools are required to provide equal opportunities and funding to men’s and women’s athletic programs proportionate to the number of men and women in the student body.

At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. Detractors decry Title IX as a government-mandated “quota system” that in practice has forced colleges to cut men’s programs in sports such as gymnastics and wrestling rather than add them for women. In mid-2005, advocates of the law worried about its future, given the retirement of Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who was often the swing vote in cases expanding Title IX, and new Bush administration rules for compliance, requiring that colleges merely conduct an online survey to assess female student interest in sports programs. A lack of response would indicate lack of student interest, and excuse the college from providing any further opportunities for women to play that sport.*

* Karen Blumenthal, “Title IX’s Next Hurdle; Three Decades After Its Passage, Rule That Leveled Field for Girls Faces Test from Administration,” Wall Street Journal (eastern edition), July 6, 2005, B1.

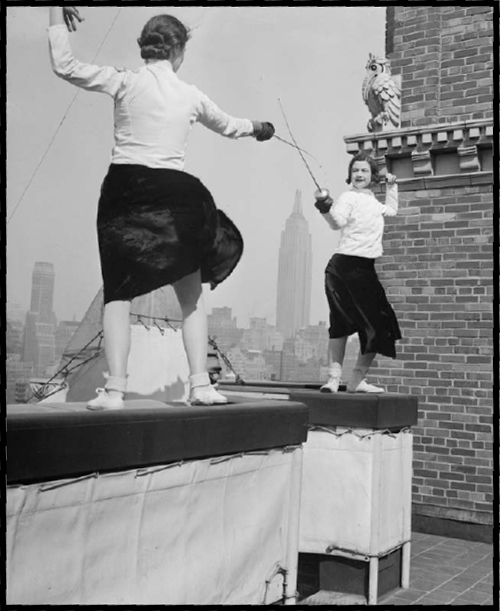

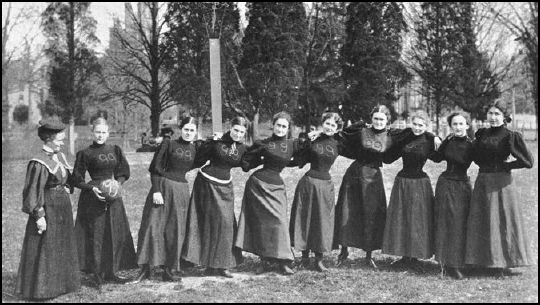

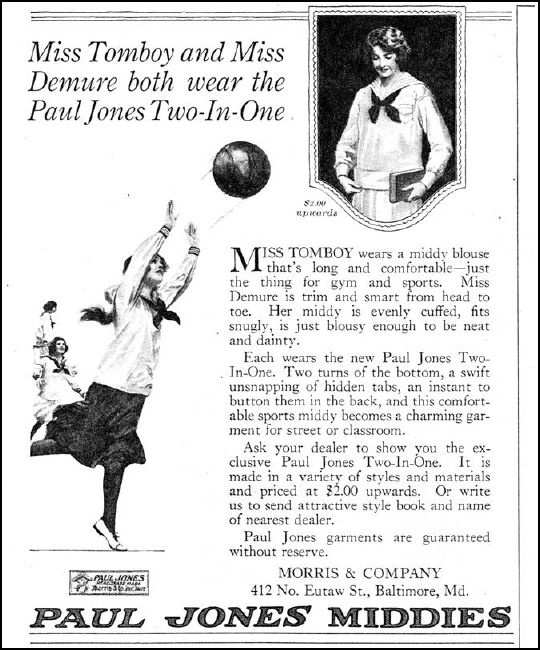

Of course, one couldn’t properly play basketball (or practice calisthenics) if one’s waist was whittled down to a fashionable twenty inches or so by a tightly laced whalebone corset. The rise of women’s athletics contributed to the downfall of the corset and similarly restrictive clothing for daily wear. Catharine Beecher, Dio Lewis, and other advocates of female calisthenics were also devotees of the dress reform movement, and sought to get women out of organ-crushing, health-impairing corsets and into looser, less restrictive inner and outer garments. Just what those new garments should look like was a matter of debate—Amelia Bloomer’s ill-fated reform outfit of shortened skirt and baggy pants is still remembered for the ridicule hurled at both it and its inventor in the early 1850s. Nevertheless, early college girls adopted gym uniforms that were essentially divided skirts gathered at the knee into the traditional “bloomer” shape worn with sailor-style middy blouses. Wearing this modified bloomer costume was acceptable in the gym and even in the classroom on some campuses, but only because its wearer was shielded from public display. For example, in 1895 the playing field at Smith College was noted to be “retired enough for the girls to play without embarrassment in gymnasium suits.” If gym-suited girls might be visible to passersby, they wore long skirts over the bloomers.34 Dressed for their team photograph in the 1898 Oriole yearbook, the members of the junior and sophomore “basket ball” teams at the all-girl Maryland College for Women in Lutherville, Maryland, ignored their gym uniforms altogether and appeared in ankle-length skirts, fashionable leg-o’-mutton sleeves, and dress reform be damned, corsets tight laced within in an inch of their young lives. These outfits were more fashionable than the baggy, natural-waisted middy blouses and shorter skirts (not bloomers) worn on the outside playing field, and which the freshmen class of 1900 wore for their team picture, although one member flaunted convention and shortened her skirt almost to her knees.

The fashionably tight-laced sophomore basketball team at the Maryland College for Women, 1898.

In the nineteenth century, as in our own, the prophets of doom appeared whenever girls had too much fun. There were concerns about girls playing a men’s game according to the men’s rules, questions regarding how vigorous play affected women’s health, or whether competition compromised players’ femininity. In Confidential Chats with Girls (1911), Dr. William Lee Howard warned girls about these and other dangers of athletics. Crashing down court in a jostling group of fellow players, leaping high to toss ball into basket or block another’s shot, few girls worried about their reproductive organs—but Dr. Howard did. He focused his readers’ attention by placing key words and phrases in capital letters:

Many a foolish or uninstructed girl has made herself a girl of muscles, but ruined her WOMANLY POWERS in so doing. Save all your strength for what Nature intended a woman to DO; don’t throw it away in doing gymnasium stunts. . . . Such a girl may have strong arms in which to carry a baby, but the chances are that some other woman will have to give her the baby to carry.35

The freshman basketball team displays its uniforms. Maryland College for Women, 1898.

A girl’s muscular arms, it seemed, wouldn’t help keep her uterus anchored in the proper place. As described by Howard, the female organs were suspended—barely—by delicate cords (“Never mind the names the doctors call these cords or other ligaments,” he snapped at curious readers) which could be jarred loose at almost any second, especially while a girl was still growing. “[I]t takes but little to put [the womb] out of place and have it stay there. The ovaries may be so twisted and put out of order that nothing can be done for them in later life but to cut them out with a knife; then you are ruined as far as womanhood is concerned.”36

It was a frightening vision of the uterus broken loose from its strings like an out-of-control Macy’s Parade balloon tangled in telephone wires on a windy day. Howard later took what promised to be a more sensible tack before he stumbled into a syntactical abyss: “Of course, every girl must exercise, but it must be such exercises as is governed with her sexual organs ever in view.”37 Mental images of naked Twister contests twirl in the modern reader’s head, but all he meant was that girls needed to be ever vigilant of their delicate reproductive systems: walking, dancing, even swimming (of course never during the menstrual period) were all acceptably gentle forms of exercise.

As for the types of sports that had taken the women’s colleges and female departments of coed campuses by storm, the dangers were far beyond mere physical strain:

You can over-exercise, become too much excited over contests in the gymnasium . . . No girl of a nervous temperament should go into any athletic contest, team or personal. Such a girl should not play basketball, attempt any stunts on horizontal bars or flying rings . . . Hundreds of girls who are playing contests of basketball, to see which team is going to be the champion of the state or the town, are going to suffer from this excitement.38

Like the author of Sex in Education a generation or so before him, Howard understood that a young woman’s reproductive system was at its most vulnerable in the first years after menarche. Athletic excitement of the sort engendered by gymnastics or basketball at this crucial time caused “growing womanly functions [to] become weakened and sometimes dried up.” Rather than training for athletic competition, a girl between the ages of fourteen and twenty was better served by preparation “for her future work—motherhood.”39

Even proponents of women’s athletics worried about their masculinizing effects. Dr. Dudley A. Sargent was the director of Harvard’s Hemenway Gymnasium from 1879 until 1919. He oversaw the gymnasium work of Radcliffe students, and developed a system of exercises performed on special machines that was incorporated into Wellesley’s gymnasium in the early 1880s.40 He also wielded a prolific pen. In 1912, he presented an up-to-date summation on women and sports when he tackled the question “Are Athletics Making Girls Masculine?”

Sargent’s response was a decided “it depends.” He believed that women could take part in almost all athletic endeavors without fear of injury and “with great prospects of success,” even though gym work and sports modified the conventional female figure with its “narrow waist, broad and massive hips and large thighs” into something more masculine, with a stronger back and more expansive chest. Women developed beneficial mental qualities in the gym or on the playing field: concentration, will, perseverance, reason, judgment, courage, strength, and endurance were just a few in an exhaustive list. Only a few sports made women “masculine in an objectionable sense,” but among them were campus favorites baseball and basketball. These were men’s games, and when played by men’s rules they were rough, strenuous, and afforded the opportunity for “violent personal encounter,” which most women found “distasteful.” Combined with the “peculiar constitution of [the female] nervous system and the great emotional disturbances” to which girls and women were subject both on and off the playing field, these games held the potential for disaster:41

I am often asked: “Are girls overdoing athletics at school and college?” I have no hesitation in saying that in many of the schools where basketball is being played according to the rules for boys many girls are injuring themselves in playing this game. The numerous reports of these girls breaking down with heart trouble or a nervous collapse are mostly too well founded.42

In addition to physical breakdown, Sargent ominously noted there was “some danger” that women who played these unreconstituted men’s sports might “take on more marked masculine characteristics” than simply stronger backs and broader waists. “Many people,” he reported, believed that athletics made girls “bold,” “overassertive,” and robbed them of “that charm and elusiveness that has so long characterized the female sex.”43

Girls had been playing basketball for almost twenty years on some college campuses and they clearly enjoyed it. How then did they keep from “breaking down” physically and/or otherwise compromising their femininity while at the same time reaping the healthful benefits of playing basketball? In 1899, Senda Berenson, Smith College’s athletic director and the “mother of women’s basketball,” organized a committee comprising women educators to investigate the matter. Their solution was to modify the rules to remove “undue physical exertion” from the game.44 Among other changes, the modified rules restricted players’ movement on the court to one of three assigned zones, prohibited girls from snatching the ball from one another (which was seen to encourage rough play), and forbade any one of them from making more than three dribbles of the ball (a 1928 guide to women’s basketball cryptically stated, without further explanation, that many of the committee felt there was a “possible danger in the dribble”).45 In addition to limiting the physical exertion needed to play the game, the rule modifications made the game more psychologically “feminine” by eliminating what the basketball committee referred to as “star playing” while encouraging “equalization of team-work.”46 This meant that players submerged their individual egos for the good of the team, just as women were reminded to practice self-denial for the good of their families. In the words of historian Barbara A. Schreier, “the result was transformation of a man’s sport into a women’s game.”47

The first women’s basketball rule book was issued in 1901, though it’s apparent from Sargent’s article that almost fifteen years later not all colleges employed it. Even before the “girls’ rules” went into effect, though, boosters described how athletic contests on their campuses emphasized feminine cooperation instead of masculine competition. As the wife of Smith’s president, essayist Harriet C. Seelye was no doubt trying to counter negative images of hoydenish girls who lost self-control on the court and became “rough, loud-voiced and bold.”48 In an 1895 article, she described how the “feminine character of the college [was] clearly revealed in the manner” in which formerly male collegiate sports like basketball and baseball were played by the girls. “No charge of masculinity” could be made against girls playing baseball after dinner in long dresses (on at least one occasion it was observed that “the pitcher wore a ruffled white muslin with a train for good measure”).49

Middy blouses were the height of casual comfort in 1922.

While the strenuous nature of basketball required gym suits instead of formal wear, Seelye wrote, the girls who played the game at Smith developed “grace, self-control, and politeness”: “In a Harvard-Yale football contest one does not hear opponents saying at an exciting crisis, ‘Pardon me, but I think that’s our ball,’ or ‘Excuse me, did I hurt you?’ ”50

Such idealized teamwork and cooperation were the bywords in women’s collegiate athletics for years to come. In 1940, the authors of She’s Off to College described the important life lessons a girl learned when she sublimated her individual will to the greater good of the team:

A girl learns not to make a grandstand play, not to show off her own skill, but to subordinate her playing to the success of her team. She doesn’t cheat. She doesn’t call a ball in that’s out. She doesn’t slouch in the ranks. She plays with all her ability, skill, and good will. These qualities become a part of her and are carried over into other departments of her life, making her a good all-round sport in whatever she undertakes, at college or later.51

In this sense, the girl who became a “good all-round sport” was analogous to the girl who was “smart enough”: both appellations indicated levels of achievement that didn’t threaten male superiority. Good all-round sports learned (or so educators hoped) patience, obedience, self-control, self-denial, and submergence of self—qualities that conformed to traditional views of nonassertive femininity, in the classroom, the home, or the office—and certainly not the “will” Sargent placed near the top of his list of qualities women might obtain on the basketball court. It was a short hop from becoming a good all-round sport on the playing field to “being a good sport” wholly divorced from any athletic connotation in real life. Being a good sport was an attribute that often showed up in midcentury dating manuals’ lists of qualities boys liked in girls. In its most frequently used context, being a good sport meant being a member of the get-along gang, and not bothering one’s date by complaining or being bossy. According to CO-EDiquette, being a good sport at a football game meant wearing clothing that could stand the rough-and-tumble of outdoor stadium seating, because “if you can’t sit down because the step is dirty and if you melt in a drizzle, you will be as welcome as white satin at a picnic.”52

It wasn’t until the 1950s that women physical-education teachers sought to eliminate the distinctions between men and women’s basketball.53

The Unladylike Nature of Competition

Competition itself was a vexing issue for the administrators of women’s athletic programs. On the one hand, they acknowledged competition was increasingly important to the American way of life—”why not prepare for it in the gymnasium,” asked Bryn Mawr’s director of physical culture in 1904.54 At precisely the same time, administrators at Smith felt that intercollegiate athletic contests were not in “good taste” where its students were concerned—hence those oh-so-polite basketball players. “Valuable as such contests may be for men,” deemed President Seelye, “they do not seem suitable for women, and no benefit is likely to come from them which would justify the risks.”55

Competition was at the root of a problem that factionalized the coeducational campus of Morningside College in Sioux City, Iowa, at the turn of the century. The matter at issue was whether a young woman who could sprint “faster than any man in the school” at fifty and one-hundred yards should be allowed to attend the state intercollegiate track meet. Not surprisingly, the coeds demanded to know why their colleague was denied the opportunity to compete—and quite possibly win—against men. The author of The College Girl of America (1905) deemed the imbroglio as evidence of the “unwomanly direction” competition might take.

A quarter of a century later, with woman suffrage secured and a place on the wider stage of public life seemingly assured, Alice Frymir, the author of Basket Ball for Women (1928), acknowledged the individual’s need to “engage with others in some form or other of competition when he enters his life work. Modern woman has taken her place in the world: in business, in profession, in politics. She, too, must meet the situations as they exist.”56 It was the fervent hope of the Women’s Division of the National Amateur Athletic Federation that she would meet those situations in a ladylike fashion. Founded in 1923, the Women’s Division adopted a platform for girls’ and women’s athletics that emphasized the ideals of team play and recreation over personal glory gained in the heat of competition:

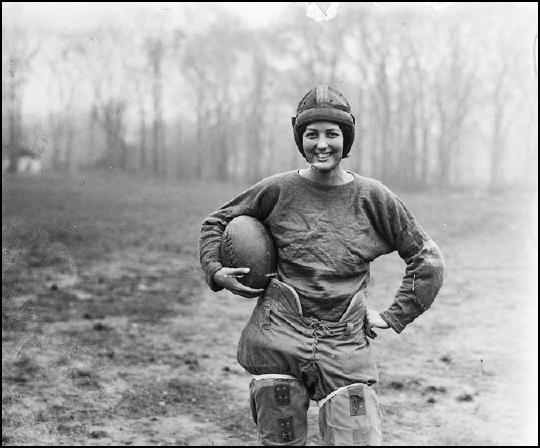

In 1925, Upsala College in East Orange, New Jersey, had a women’s football team led by Gladys Scherer, “the Red Grange of woman football.” News accounts noted that her team “tackled football with the same enthusiasm that they formerly tackled dancing.”

4. Resolved, In order to develop those qualities which shall fit girls and women to perform their function as citizens, . . .

(b) That schools and other organizations shall stress enjoyment of the sport and development of sportsmanship, and minimize the emphasis which is at present laid upon individual accomplishment and the winning of championships.57

Coaches and educators needed to keep “the educational value of the game in mind rather than winning.” Under these conditions, intramural and even interschool play was permissible (unless a girl was in the first three days of her menstrual period, in which case she needed to sideline herself both during practice and on game day).58

To further curb the disruptive effects of overstimulation on delicate female constitutions, most colleges spurned women’s interschool competition in favor of intramurals—games played between classes or other arbitrary divisions. In the event two schools met, teams were sometimes mixed and divided on the spot, thus cutting out the element of rivalry that led to rough and combative play.59 “Play days” and “sports days” in which girls from different colleges took part in noncompetitive games further reinforced the ideals of team play and sportsmanship. Just prior to Hood College’s first play day in February 1931, an editorial in the student newspaper explained that “the spirit which we aim to foster . . . is not one of inter-collegiate rivalry, but one of team co-operation which definitely contributes to the fostering of sport for sports sake.”60

At Hood’s play day, freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior basketball teams met corresponding class teams from two visiting colleges. Winning was so unimportant that neither the editorial nor another descriptive article in the same issue of the student paper bothered to explain how—or even if—an overall victor would be chosen.

Some schools further eroded the possibility for competitive interschool rivalries by conducting their sports or play days via post or wire. On the appointed day, a college’s class teams played one another and mailed the resulting scores to another participating college, where, on the same day, that school’s class teams played one another. The scores were compared, and a winning school determined. Given the inevitable lag time, who cared who won? Certainly some did—but enthusiasm is hard to maintain over days or weeks waiting for the mail. Telegraphing the results sped up the process, but physical isolation during the actual games prevented anything so disgraceful as partisan rooting. As late as 1950, a glossy magazine photo of underclassmen playing field hockey at Smith was accompanied by a caption which noted that competition was “between houses and classes, never with other colleges.”61

The fear of competition trickled down into other gendered arenas of life—specifically dating. Mid-twentieth century dating manuals often recommended sports as ideal date activities: they were fun, you didn’t have to talk all the time, and there was an underlying suggestion that they provided a safe outlet for pent-up teenage sexuality. But they also provided a dilemma for girls who were better athletes than their dates: should they play to the best of their abilities and possibly win, or should they throw the game and lose in order to avoid embarrassing their date? Women were constantly reminded that competition with men was strictly verboten. If anything, a beau wanted a helpless little girl by his side, not a competent, muscular Amazon. Being a good sport could mean being a namby-pamby competitor.

Undergraduates were recommended to choose a sport that a future husband would be likely to play—something along the lines of tennis or golf. “Girls nowadays . . . are mainly looking for a chance to improve their skill in individual sports which they can use the rest of their lives,” stated a New York Times report on the “new freedom” of the college girl. “A girl today who can’t swim and play tennis is considered a dub [i.e., “dud”].”62 This nixed two of the most popular women’s college sports for postgraduation fun, because a hypothetical husband wouldn’t want “to cross field hockey sticks with you or shoot a basket or two when he comes home from work,” as Mademoiselle confidently stated in 1940.63

Advice writers regularly reinforced this idea to their teen girl (and adult woman) readers. If you insisted on winning, even at golf, you had better be prepared to feign incompetence in other ways according to Seventeen in 1959:

Q: I am sixteen and in perfect health. I swim, ride, play tennis and regularly beat my beau at golf. Why then—when I’m out on a date—do I have to pretend to be so helpless I can’t open a car door!

A: It’s a penalty for beating your beau at golf! Actually, it is a pretense—but a nice one. It gives your escort much the same protective feeling you get taking a child’s hand to cross a street. Cater to it.64

Good thing the girl who went out for athletics wasn’t necessarily doing so because she enjoyed sports. She knew that the quickest way to a man’s heart was not necessarily through his stomach. As Mademoiselle pointed out in 1940. “There’s no better way to make and keep friends, and in particular that top man, a husband, than to play his favorite game—and play it well.”65

The Freshman Five: Eating and Dieting

Ideally, a rousing game of basketball or spirited round of calisthenics helped a girl balance the calories she took in, which from the amount and range of food provided at meals, must have been formidable. Sarah Tyson Rorer made an investigative tour of several college campuses in 1905 and reported her findings in a Ladies Home Journal article titled “What College Girls Eat.” Rorer battled against difficult-to-digest foods (including, as we have seen, pies and pastries) and for a “hygienic table” of nutritious viands. She was happy to report that Northwestern employed a trained dietician (a modern innovation at the turn of the century), but overall her impression was a negative one. “To kill the weak and ruin the middling is too great a price to pay for even a college education. The heavy breakfasts with course luncheons and heavy dinners, with teas and ‘fudges’ between and after, will, I am sure ruin the physique of any woman.”66 The sample menus Rorer provided proved no one went hungry, even on those campuses with modern ideas about digestible foods—where one might expect to find lighter fare. Breakfasts consisted of fruit, cereal, cream, eggs, biscuits or toast, and coffee. At noon a girl might sit down to a meal of tomato soup, fried veal, mashed potatoes, peas, and stewed celery, topped off with panned apples and cream. Supper was a smaller meal: pressed chicken with mayonnaise dressing, potato chips, olives, canned fruit, and cake.

For the most part, girls thrived on the board they received at college. “Everything is excellent and well and thoroughly cooked,” reported Wellesley student Charlotte Conant to her parents in 1880.67 “We are both growing fatter,” wrote Smith student Alice Miller, speaking for herself and her sister, to their parents in 1883.68 In her study of college women and body image from 1875 to 1930, historian Margaret Lowe has shown how early college girls accepted modest weight gain as a sign of “a healthy adjustment to college life” instead of the alarming development it would become. “It is my ambition to weigh 150 pounds,” wrote Charlotte Wilkinson in a February 1892 letter home. By April, her weight was 1351/2; two months later she proudly informed her mother that it was up to 137. 69

College girls well knew at any given time how much they weighed because their weight and other vital statistics were carefully monitored. This happened on men’s campuses as well, but it took on a special significance at women’s schools in response to the medical profession’s warnings about the effect of higher education on women’s health. Freshmen were subject to a rigorous inspection at the beginning of the school year. Following the nineteenth-century vogue for anthropometry (a pseudoscience that used body measurements to draw anthropological conclusions), girls were asked to strip down, slip on a hospital-gown-like garment, and a detailed set of measurements were made. In addition to height and weight, the circumference of head, neck, thighs, calves, ankles, upper arms, elbows, and wrists might be taken, along with the length of one’s head, various measurements from hips to heels, and so on. On some campuses, the exam was repeated at the end of the school year and both sets of results were compared with the average. “Suggestions for special exercises, suitable to the individual needs of the student” were based on these examinations.70 Both students and administrators could easily track a girl’s progress toward health.

Anthropometry in Action, or How Do You Measure Up?

Dudley A. Sargent, M.D., was an early booster of physical education for both men and women (as long as they didn’t overdo it). As director of the Harvard gym from 1879 to 1919, he oversaw the anthropometric measuring of several generations of Harvard freshmen. In 1912, he provided the following ideal feminine measurements for what he termed “A Fine Type of Athletic Figure” in the March issue of the Ladies Home Journal. Get out your tape measure and see where you fit in! And while you’re at it, remember those poor college girls at the turn of the century who were subjected to a similar frenzy of measuring—sometimes twice a year.

Dudley A. Sargent, M.D., was an early booster of physical education for both men and women (as long as they didn’t overdo it). As director of the Harvard gym from 1879 to 1919, he oversaw the anthropometric measuring of several generations of Harvard freshmen. In 1912, he provided the following ideal feminine measurements for what he termed “A Fine Type of Athletic Figure” in the March issue of the Ladies Home Journal. Get out your tape measure and see where you fit in! And while you’re at it, remember those poor college girls at the turn of the century who were subjected to a similar frenzy of measuring—sometimes twice a year.

|

INCHES |

INCHES |

||

|

Weight, 118 pounds |

|||

|

Height, standing |

61¾ |

Girth of Thigh |

21 |

|

Height, sitting |

33½ |

Girth of Calf (right) |

13½ |

|

Girth of Neck |

13½ |

Girth of Calf (left) |

13¼ |

|

Girth of Chest |

31½ |

Girth of Ankle |

8 |

|

Girth of Chest Full |

33½ |

Girth of Upper Arm |

10¾ |

|

Girth of Lower Chest |

27½ |

Girth of Forearm |

9½ |

|

Girth of Lower Chest, Full |

29½ |

Girth of Wrist |

6 |

|

Girth of Waist |

23¼ |

Breadth of Waist |

8 |

|

Girth of Hips |

35¼ |

Breadth of Hips |

12½ |

It is certain that college girls ate with relish. Following Princeton’s tradition of eating clubs (a lack of dining facilities in the 1850s led students to take their meals off campus, and the resulting clubs evolved into social groups resembling fraternities), Vassar students had supper clubs. Ten pages of the 1904 Vassarion yearbook were devoted to these alliances, among them the “Nine Nimble Nibblers” and “The Bakers’ Dozen.” Members of the latter increased their dining pleasure by adopting special snacking names such as “G. Inger Snap” and “Grid L. Kakes.” Around the same time, the New York Times described the eating clubs at “one of the Massachusetts colleges”:

one calls itself the “Bow-wows,” meeting at intervals to cook “hot dogs”—as frankfurter sausages are called—and wearing china puppies attached to bits of blue ribbon. Another, “The Eating Six,” takes Sunday morning breakfasts together. The “Stuffers” have for their motto, “Eat, stuff, and be merry, for to-morrow, ye flunk.”71

The Stuffers made it a point to cook and consume meals in a member’s room, and the ingredients could only be purchased using the ten cents gathered from each girl. One thrifty menu consisted of fruit salad, omelets, and ice cream. When penury reared its ugly head and not even a dime was available, the Stuffers shamelessly wrote a story that asked “What is more agonizing than to see an innocent child enduring the pangs of hunger?” After a gullible Sunday school paper purchased the story, the Stuffers rewarded themselves with a high-ticket dinner costing twenty cents a head.72

Today one would be hard-pressed to find a group of college girls who so proudly admitted their lusty gustatory appetites. Clearly, the Stuffers and their cohort had a different relationship with food than we currently do, one seemingly less fraught with anxiety—though concerns about size and appearance were never entirely absent. Lowe mentions an overweight college girl in the 1880s who begged her mother to keep her weight gain a secret from the family physician “or he’d never have any respect for me again.”73 Nevertheless, at the turn of the twentieth century, the standard of physical beauty for women was quite different from the Botox-smoothed, collagen-plumped, extra-attenuated, ultrathin model with implants that rules the media today. In 1912, Miss Elsie Scheel of Brooklyn, New York, was deemed the “most nearly perfect specimen of womanhood” among Cornell’s four hundred coeds. Scheel was twenty-four years old, stood five feet seven inches tall, weighed in at a healthy 171 pounds (her favorite food was beefsteak), and possessed a decidedly pear-shaped figure (it measured 35-30-40). Nevertheless, Cornell’s medical examiner—the woman who measured all those coeds—judged her “the perfect girl,” having “not a single defect” in her physical makeup. (She was also “an ardent suffragette” who “if she were a man . . . would study mechanical engineering” but instead studied horticulture.)74

The Freshman Five (or More)

In 1950, design-heavy FLAIR magazine polled an undisclosed number of male and female college freshmen (only college girls were pictured) on their eating habits and weight. On average, each gained eight pounds. Students blamed the extra poundage not on mass-produced cafeteria grub but snacking. And what were the most popular between-meal yummies on college campuses that year? The top responses were:

In 1950, design-heavy FLAIR magazine polled an undisclosed number of male and female college freshmen (only college girls were pictured) on their eating habits and weight. On average, each gained eight pounds. Students blamed the extra poundage not on mass-produced cafeteria grub but snacking. And what were the most popular between-meal yummies on college campuses that year? The top responses were:

1. Cola drinks;

2. Coffee;

3. Milkshakes and malteds (a recipe from all-male Haverford College read “2 scoops ice cream; 1 pint milk; 1 squirt vanilla; Syrup; and beat like hell on the mixer”);

4. Beer (“or beer, beer, beer as it was written on almost all the answers from men’s colleges . . .”)

Barring the number two choice, all of these packed a caloric punch, especially in combination with the runners-up: all manner of ice-cream sodas, hamburgers, grilled-cheese sandwiches, cheese crackers, popcorn, potato chips, French fries, peanuts, candy bars, sundaes, and “anything a la mode,” as well as a fascinating array of regional goodies, including “spudnuts” (potato-flour doughnuts popular at Southern Methodist University), crème de menthe mixed with beer (a taste treat at Middlebury), and peanut butter/bacon/banana sandwiches (a favorite at the University of Maryland).*

* “Statistics Behind College Figures,” FLAIR, August 1950, 58.

Alas for Elsie Scheel and everyone else built along her solid lines, the flapper popularized the boyish figure after World War I. Mr. J. R. Bolton, a fashion expert consulted by the New York Times in 1923, blamed the “athletic tendencies of the modern girl” for the shift to extreme slenderness. The newly ideal girl was five feet seven inches tall and a “perfect 34, with 22-inch waist and 34-inch hips. The ankle should measure 8 inches and the weight not exceed 110 pounds.” It was a youthful figure; American women reached their “best proportions at the age of 20,” Bolton pronounced. Not surprisingly, “abstinence from candy and pastry” along with “plenty of exercise” were required to maintain this standard of perfection.75

By the mid-1920s, reducing diets were the new “national pastime . . . a craze, a national fanaticism, a frenzy,” according to one journalist, and college girls were not immune. In 1924, the Smith College Weekly published a letter to the editor under the headline “To Diet or Not to Die Yet?” in which a group of girls warned that unless “preventative measures against strenuous dieting” were taken soon, the campus would become “notorious, not for the sylph-like forms but for the haggard faces and dull, listless eyes of her students.” A speaker at the American Dietetic Association convention in 1926 warned that “thousands of young girls in schools, colleges and offices were not dieting as they fondly believed, but starving themselves.” Modern girls, it seemed, were “so afraid of being overweight” that they were “not willing to be even normal in weight.”76 (Sound familiar, Jane Doe?) The fear of fat had disastrous consequences in 1930, when a nineteen-year-old New York University freshman committed suicide after her weight ballooned from 130 to 235 in the course of a year because of a “glandular disorder.” The dean of students believed that embarrassment over her size contributed to her difficulties with studies, though he didn’t go so far as to suggest that it also contributed to her death.77

Mental Health

Sadly, there was nothing new about college girl suicide in 1930. Worries about test results, grades, and living up to parental expectations were as familiar to nineteenth- and twentieth-century college girls as they are to today’s students. The New York Times was filled with stories of college girls who found such pressures too great to bear. In September 1884, nineteen-year-old Flora Meyers failed an examination at the unnamed “female college” she attended. Rather than face her parents, she penned a pathetic note in which she described the last five years as nothing but “worry, worry, worry, until I have envied the girls I have seen with scrubbing brushes.” She, too, was “fit only for servile labor,” she told her parents, whom she could “no longer bear to see . . . slave any longer” for her tuition. And with that, she disappeared. Her distraught father hired a private detective, who searched the morgue and scanned the faces of passing factory and shop girls before Flora was found by a neighbor—working as a servant in a New York City household.78

Flora’s story had a happy ending (though not for the private detective, who had to sue for payment), but many others didn’t. In 1897, Bertha Mellish left her dormitory at Mount Holyoke College. It was presumed that she was headed toward the post office, a three-minute walk away, but Bertha never returned. She was bright, studious, and well liked by both faculty and classmates. Ominously, she was also reported to have written a story “in which she described vividly the sensations and thoughts of a girl who committed suicide by drowning.” Combined with the discovery of “small footprints” leading to a bluff over the Connecticut River and, nine months later, a woman’s foot encased in a “black stocking and low shoe” found in a meadow at the river’s edge, it was assumed that she had in fact taken her own life.79

College Girl Bookshelf: “The Bell Jar” (1971), by Sylvia Plath

The undisputed classic of college-girl alienation, Sylvia Plath’s autobiographical novel of adolescent identity crisis and mental illness was originally published under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas in England, Plath’s adopted home, a month before her suicide in 1963. It received good reviews from the British press, but American publishers rejected it based on the brutal description in the second half of the novel of Esther’s life in a mental institute. It took another eight years for its publication in the United States, where it immediately found a home on the best-seller list and became required reading in many high-school English classes.

The undisputed classic of college-girl alienation, Sylvia Plath’s autobiographical novel of adolescent identity crisis and mental illness was originally published under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas in England, Plath’s adopted home, a month before her suicide in 1963. It received good reviews from the British press, but American publishers rejected it based on the brutal description in the second half of the novel of Esther’s life in a mental institute. It took another eight years for its publication in the United States, where it immediately found a home on the best-seller list and became required reading in many high-school English classes.

That’s probably where I read The Bell Jar for the first time, though I don’t remember exactly when. I do know that it was definitely prior to losing my virginity. I say this because what stuck with me was the protagonist’s description of her disappointing first sexual experience and how boyfriend Buddy’s equipment reminded her of a “turkey neck and turkey gizzards,” a description that left me both terrified and fascinated.

I next read The Bell Jar when I was well into my thirties, happily married (no scary Mr. Turkey Neck here!) and satisfied with life in general. This time I was struck by how well Plath’s description of the onset of Esther’s mental illness fit what I remember of the almost clinically deep depression that descended on my college years: “I was going to cry. I didn’t know why I was going to cry, but I knew that if anybody else spoke to me or looked at me too closely the tears would fly out of my eyes and the sobs would fly out of my throat and I’d cry for a week.”*

I, too, was subject to overwhelming waves of sorrow, tears that gushed out when I least expected and that were impossible to control. Unlike Plath, therapy helped me find a way to adult happiness, if not her enshrinement as a literary lion (and given Plath’s sad end, I’ll gladly take the former).

* Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar (1963; New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 112, 75.

In the decades to come, Bertha’s sad story was repeated over and over again on campuses throughout the United States. Girls waded into college lakes, overdosed on laudanum, took poison, breathed gas, and jumped from dormitory or boardinghouse windows. Indeed, student suicides were a familiar enough spectacle by 1878 that Olive San Louie Anderson included one in An American Girl and Her Four Years in a Boys’ College (the freshman girl who shoots herself thoughtfully leaves a note absolving coeducation for her rash act, blaming instead a “hereditary mental disease”).

Ballyhoo Girl

Suicide was not the only way college girls dealt with the pressures of life. In August 1935, a month after she disappeared from Antioch College, twenty-one-year-old Anne Sibley was discovered working as a “ballyhoo girl” at a sideshow on Coney Island. “Seen Daily with Freaks” read a New York Times headline (an exclamation point was implied). No fancy college degree was required. All she needed to do was “look pleasant and say nothing while the freaks were being paraded on the front platform.” Anne also sold tickets and appeared as The Woman with the Disappearing Head. Perhaps most shockingly for the times (when only sailors and criminals inked their skin), she roomed with the show’s tattooed lady.*

Suicide was not the only way college girls dealt with the pressures of life. In August 1935, a month after she disappeared from Antioch College, twenty-one-year-old Anne Sibley was discovered working as a “ballyhoo girl” at a sideshow on Coney Island. “Seen Daily with Freaks” read a New York Times headline (an exclamation point was implied). No fancy college degree was required. All she needed to do was “look pleasant and say nothing while the freaks were being paraded on the front platform.” Anne also sold tickets and appeared as The Woman with the Disappearing Head. Perhaps most shockingly for the times (when only sailors and criminals inked their skin), she roomed with the show’s tattooed lady.*

The story rated mentions in newspapers from Detroit to New York, Time magazine, and Westbrook Pegler’s controversial column. In the hands of the press, it became a titillating spectacle of a high-toned, upper-class college girl (Anne’s father was a Chicago attorney) forced to come down a notch or two. “I learned more at Coney Island in one month than I did in a year at college,” she told detectives (who told reporters).† When it was revealed that Anne had flunked out of Antioch before her disappearance, the story’s luster dimmed. Who cared that a troubled young woman ran away? An attractive coed turned carnival barker—now that was a story. Only a few local papers bothered to mention that months earlier Anne had been involved in a fatal accident when a motorist swerved to avoid her bicycle, an incident that may well have been behind both her bad grades and flight to Coney Island.

* “Lost College Girl Found Inside Side-Show,” New York Times, August 4, 1935, 1; “Runaway Girl Student ‘Barking’ for Coney Island Show,” New York Times, August 5, 1935, 17.

† “Missing Ohio Coed Found at Coney Island,” Baltimore Sun, August 4, 1935.

Up through the late 1930s, many of these deaths were attributed to a nebulous condition known as “overstudy.” This was different from the loopiness that results from staying up thirty-six hours straight cramming for exams or the performance failure that sometimes results from the same—something with which most current and former students will be well acquainted. It was also different from the breakdowns that college girls were alleged to suffer because of the deadly combination of study and menstruation. According to late-nineteenth-century medical wisdom, the true danger of overstudy was that it led to more severe forms of mental illness. An 1883 textbook on insanity said the condition precipitated “grave delirium,” a “rare form of derangement” that caused stricken individuals to pass from delirious excitement to apathy to death in months, if not weeks. The “unbalancing influences of overstudy” were also said to bring on paranoia (a condition one writer in 1892 called “a modern form of insanity”).80 Both men and women were susceptible: an 1875 pharmaceutical dictionary prescribed phosphide of zinc for “impotence of a cerebral origin, i.e., when caused by overstudy.” No one, however, suggested that higher education for men was a bad idea because it had a damaging effect on the delicate male reproductive system.81

Occasionally, overstudy was posited as the root cause for bad behavior. When a student at New York City’s Normal College stole $1,800 worth of jewelry (a small fortune in 1903, when the robbery occurred) from the home of a “schoolgirl chum,” her father told the authorities that his daughter’s behavior resulted from “nervous prostration brought on through over-study and close application to her scholastic work.” This was damage control. The girl had earlier told police that she took the items because “she couldn’t bear to be without pretty clothing such as her girl friends wore.” Considered alongside the pawn tickets and stolen goods found in her room, her confession suggested full cognizance of her actions. However, a victim of overstudy didn’t quite know what she was doing, and deserved pity and treatment rather than jail time. Her father’s argument worked: the girl was not charged. 82

Similarly, overstudy was a convenient excuse when the circumstances behind a student suicide proved embarrassing to parents or inconvenient to academic institutions. When a male student at Wittenberg College in Springfield, Ohio, died at the Columbus State Hospital for the Insane in 1910, his parents blamed hazing for the “severe nervous shock” that led to his death. The school, however, shifted the question of responsibility (and perhaps liability) from itself to the student, declaring that overstudy caused the boy’s insanity.83 The parents of a male student at Bates College who committed suicide in 1927 probably found it less disturbing to publicly (and perhaps privately) blame overstudy than ascribe any other meaning to the “deep friendship” between their son and the male professor to whom he addressed an unfinished last letter beginning “My dear daddy.”84

Though a benefactor gave Wellesley a dormitory in 1881 to be used specifically as “a home for young ladies who may be fatigued by overstudy” and needed deep rest unobtainable elsewhere on campus, Princeton opened what is officially considered the first student mental health clinic in 1910.85 It wasn’t until the following decade that the idea of student mental health (or in contemporary terms, “mental hygiene”) really took off, nudged along, no doubt, by popular interest in Freud and his work. Student psych services were available at a special clinic at Vassar beginning in 1923. Sadly, the New York Times reported a stunning twenty-six student suicides during the first three months of 1927, thirteen at colleges or universities, thirteen at what the Times called “lower schools.”86

Reading early to mid-twentieth-century advice books for college students, one wouldn’t imagine that the need for student mental health clinics existed. Most books made college sound like a four-year-long party, full of fun and laughter. When depression was mentioned, it was as something over which a student easily had control. The Freshman Girl (1925) briefly warned against “neurasthenia”—a soon to be outmoded term for nervous debility brought on by modern living. “Such an abnormal state of mind renders you a prey to a thousand groundless fears, robs you of the enjoyments of life, and makes you more or less of a nuisance to your friends.” A “normal, healthy girl” could avoid it by not falling prey to “overanxiety” about her bodily functions.87

But what about normal, healthy girls who sometimes worried and felt anxiety about grades, tuition, or relationships? According to the authors of She’s Off to College (1940), occasional depression could be avoided “by the thrills and delights of your body.” It’s not as sexy as it sounds. It merely meant the “plunge [into a swimming pool], the skating rink, dancing, a good thing to eat that’s very hot—all of them bring you back to reality with satisfaction and delight.” Physical activity certainly helps regulate one’s emotions as well as lower stress levels, but She’s Off to College suggested that with a combination of exercise and steady habits of eating, sleeping, and studying a girl could actually “select the dominant moods in which she wants to live.”88 Unpleasant feelings could be simply blinked away without consequence:

I think there is a split second in which anger hangs in the balance, just as I think there is a split second in which tears hang in the balance. They sting behind the eyelids, but one winks them back and they go away somewhere else. They do not go on forming themselves. They stop. So with anger. It freezes, and the moment of indecision passes.89

Passes, that is, until the moment one gets her ulcer diagnosed. Such advice may have made for passive mid-twentieth-century housewives, but it rarely made for happy individuals. Impulse control over sudden flare-ups was one thing, but the authors meant the complete suppression of this powerful, albeit sometimes unsettling, emotion: “the best thing we can do with anger is forget it.”90 Burying one’s emotions also benefited friends and colleagues. “Thou Shalt Not Indulge Thy Moods” was one of the ten commandments of life in the collegiate goldfish bowl offered by You Can Always Tell a Freshman (1949). “On your bad days have the grace to keep to yourself. . . . Or play ostrich and stick your head in the sand.” Bad moods were “as infectious as a nose cold, and just as unpleasant.”91

Even in the enlightened, post–women’s lib 1970s, student guidebooks rarely touched on depression. Ms. Goes to College (1975) unblushingly dealt with subjects earlier advice writers glossed over or simply ignored: human sexual anatomy, venereal disease, contraception, and recreational drug use. It even offered a chapter on adolescent identity crises. But consider how it treated “Jennifer,” who returned home deeply depressed after a fling with drugs her freshman semester, believing she hadn’t lived up to her parents’ standards. When asked what she did to end her depression, Jennifer answered: “I didn’t . . . I just hung in there and . . . just kind of hibernated.” Her mood brightened when she moved to another state, and she eventually returned to school.92 While stories like this made it clear that there was life after depression, they didn’t present much in the way of concrete help to girls currently stuck in its depths.

The “Torches of Freedom”

Prior to World War I, smoking tobacco was a mostly male habit. Smoking by women was “a sad mistake” (though one gaining in popularity), wrote the female author of Etiquette for Americans (1898):

At first—a few years ago—smoking among women was treated as a sort of lark or joke among girls who “didn’t mean anything.” Statistics of an informal collecting then showed that the habit was settling, and on the increase. . . . At the present rate of progress, women and young girls will be smoking in the streets with men. It is a horror and a crying shame; for the debasing character of the custom will inevitably destroy the delicacy of women.93

Despite the writer’s sky-is-falling tone, this shocking behavior was at the time mostly relegated to a few iconoclasts while the vast majority of American women avoided tobacco altogether. Most would have supported the position taken by the Board of Temperance, Prohibition, and Morals of the Methodist Episcopal Church which in 1919 deemed the increased use of tobacco among women “appalling” and made an “earnest appeal to women to refrain from the use of tobacco in the name of the country’s welfare.” Women’s smoking, it was feared, would lead to a decrease in “the vigor which has been characteristic of the American people.” The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union concurred, blamed the war for the increase in smoking among young men and women, and called for further research into the harmful effects of cigarette smoking on the unborn—a stance which at the time was probably seen as further evidence of the WCTU’s wet-blanket nature, but seems absolutely prescient now.94

To moralists like those in the WCTU, smoking challenged an ideal held over from the era of True Womanhood—that women were morally superior to men. In the words of historian Paula Fass, smoking “implied a promiscuous equality between men and women and was an indication that women could enjoy the same vulgar habits and ultimately also the same vices as men.” It didn’t help that smoking’s early adopters were “disreputable or defiant,” hence the habit’s association with immorality.95 The New York City alderman behind a 1922 ordinance barring women from smoking in public (and mandating fines or jail time for scofflaws) colorfully described the moral danger unloosed when a woman lit up:

[Y]oung fellows go into our restaurants to find women folks sucking cigarettes. What happens? The young fellows lose all respect for women and the next thing you know the young fellows, vampired by these smoking women, desert their homes, their wives and children, rob their employers and even commit murder so that they can get money to lavish on these smoking women. It’s all wrong and I say it’s got to stop.96

As the alderman soon found out, it was impossible to stop the wispy gray genie once it left the bottle. Women raised such a ruckus over the smoking ban that the mayor rescinded it the following day.

“Women Cigarette Fiends” were the subject of a 1922 article in the Ladies Home Journal, a publication that also excoriated that other new phenomenon, jazz. The most widely stated reason for the rise in women smokers, the Journal reported, was the “general emancipation and freedom allotted to . . . [women] in recent years.” Popular culture shared the blame: women on stage and screen could be seen “in the midst of luxury puffing away at their cigarettes,” thereby seducing audience members hungry for Hollywood sophistication to pick up a pack upon exiting the theater.97

And then there was advertising. Convinced in the late 1920s that not yet enough American women were smoking, the tobacco industry consulted pioneer public-relations man Edward L. Bernays, who in turn hired a psychoanalyst. The latter reported that since cigarettes were “equated with men” in the public mind they became “torches of freedom” in the hands of the emancipated woman. Seizing on this phrase, Bernays arranged for ten young women (alleged to be debutantes, not college girls) to march down Fifth Avenue on Easter Sunday 1929, cigarettes proudly in hand, in what was termed “The Torches of Freedom Parade.” Although scripted down to the smallest detail (a memo discussed exactly how the women should open their purses, find a cig but no matches, ask another for a light, etc.), the parade was presented as a spontaneous event and the newspapers ate it up. Women were reported to be smoking on the street in numbers greater than ever.98

Whether it was the result of brazen manipulation in the name of advertising, the siren song of popular culture, or women’s growing desire for social freedoms long claimed by men, the number of cigarettes consumed by women doubled between 1923 and 1929.99 Most of the new female smokers were young adults.

“Twelve years ago,” wrote Elizabeth Eldridge in 1936, “a girl’s smoking was regarding as a sin only a degree less scarlet than adding a bar sinister to the family escutcheon.”100 College girls who smoked in the 1920s hid their habit from dormitory matrons by using cracker boxes as ashtrays (when not in use, judiciously sprinkled crumbs concealed their true nature) and burning incense (also a favorite with those who smoked other controlled substances in later eras). Where antismoking regulations existed, getting caught with a cigarette could have serious consequences. Smokers caught with cigarettes in their rooms were among the seventeen coeds asked to leave Michigan State Normal College in 1922. The following year, two coeds at the University of Maryland were suspended for smoking at a dance (and in a very twenty-first-century move, promptly hired an attorney to represent their interests).101 Smokers risked suspension at Smith and Mount Holyoke, and the Nebraska Wesleyan Teachers College refused to issue teaching certificates to women who smoked. Schools that in the early 1920s didn’t have anticigarette rules in place, because smoking had not been a problem on campus before that, now rushed to institute them, among them Northwestern in 1922, Vassar in 1925, and the University of California in 1926.102