Where and when In winter, Red-throated Diver is the most widespread and, generally, the most plentiful diver, particularly along the east coast. Black-throated Diver is the least numerous and most localised (mainly in Scotland but with a large concentration in Gerrans Bay, Cornwall). Both species breed in Scotland, Red-throated being by far the commoner. Great Northern Diver is most numerous in the north and west, particularly in Scotland and Ireland. All three occasionally occur inland, Great Northern being the most frequent, from November onwards. White-billed Diver is a very rare winter visitor, mainly in Scotland, with a regular early spring gathering on the Outer Hebrides, principally off Lewis, and another off the north coast of Aberdeenshire. Pacific Diver was first recorded in 2007 but there have been another four records since (to 2009).

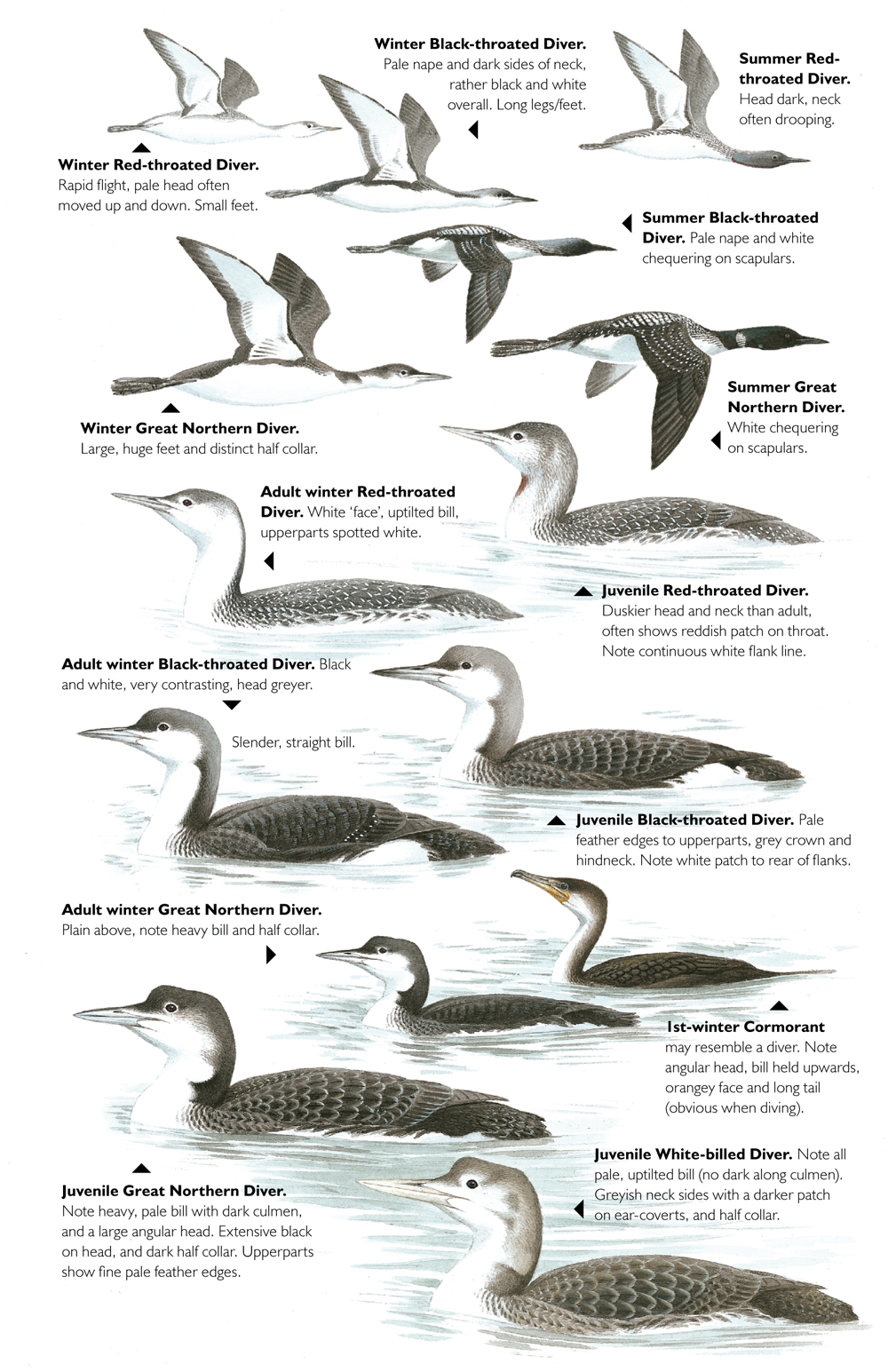

Diving actions A very easy distinction from Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo and Shag P. aristotelis is that divers do not leap out of the water to dive; neither do they have a long tail. Instead, they gently lurch the head forward and submerge gracefully with a smooth action. Diving may follow a period of underwater surveillance (or ‘snorkelling’) with the bill and head partly submerged in the water.

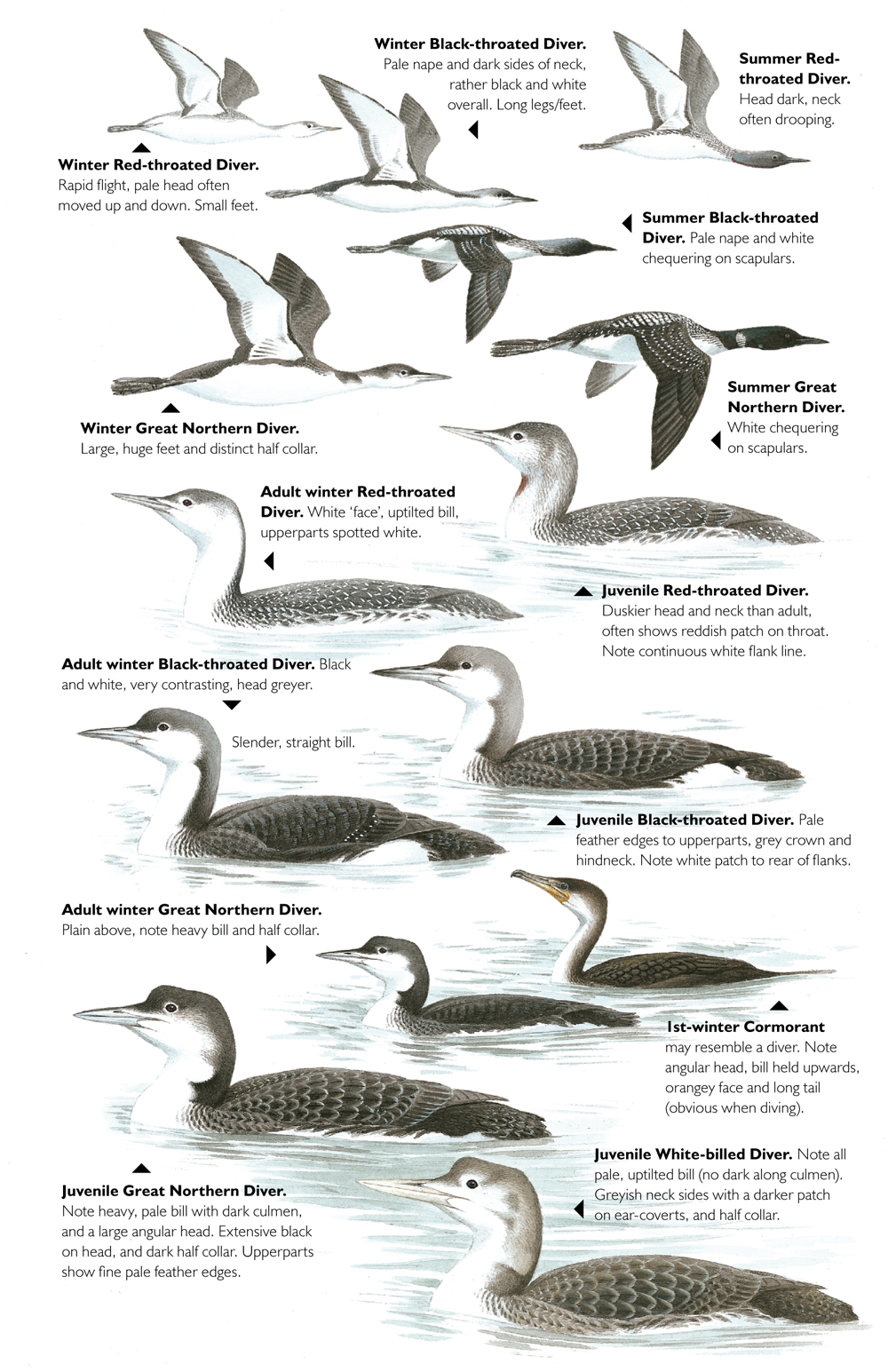

Flight identification All species have a very distinctive shape in flight: a ‘humpbacked’ appearance with the head and neck held slightly below the horizontal and the feet trailing behind. They often fly well above the horizon, sometimes in small groups (although Great Northern tends to be more solitary). Unlike most waterbirds, divers (and grebes) do not push their legs forward when landing; instead they drop belly-first onto the water, often skidding across the surface before settling. All have plain wings, which instantly separates them from grebes. Separating diver species in flight can be difficult and distant or doubtful individuals should be logged as ‘diver sp.’.

Summer plumage Note that newly arriving late autumn/early winter adults and spring adults may show variable amounts of summer plumage, very useful with migrating birds on seawatches. With the exception of Red-throated, first-summer divers do not show significant amounts of summer plumage, often becoming bleached.

Size, structure and bill The smallest diver, although it overlaps in size with Black-throated. In direct comparison, it is not much larger than Great Crested Grebe Podiceps cristatus (although c. 50% heavier). Its shape is usually distinctive, with a rather rounded back, shallow breast, full throat and rounded head. The bill is slender and usually held upwards, forming a continuous line with the throat and accentuating an upcurved lower mandible (although the upcurve can be slight). Bill generally pale in winter, appearing greyish at any distance, but may darken towards spring.

Plumage Much browner than the other species, with the crown and nape often appearing a rather dusky grey-brown; however, the upperparts can look dark at any distance. Has diagnostic white upperpart flecking (also difficult to see at any distance). The extent of white on the face is variable, but it generally extends up and around the eye (usually most obvious before the eye); classic individuals, with the eye isolated in the white face, appear rather white-headed from a distance. Compared with Black-throated, the demarcation between the dark nape and the white neck is further to the rear, producing a narrower nape line when viewed from behind. The amount of white visible on the flanks depends on the bird’s attitude on the water; when at ease, it generally shows a strip of white along the entire length of the flanks. Juvenile Before moult (generally in midwinter) juveniles are fresh and immaculate with variable amounts of fine streaking on the sides of the head and neck, obscuring the line of demarcation. On extreme examples, the whole head can look greyish from a distance, contrasting with the darker body. Juveniles may also show a dark chestnut patch on the upper foreneck, mirroring the adult’s summer plumage. They become difficult to age once juvenile plumage is lost in late winter. However, adults begin a complete post-breeding moult in early winter, so any Red-throated in active primary moult at that time will be an adult.

In flight Appears small, slim and slight with small feet producing a rather tapered rear end (foot projection about half the head and neck length). Compared to Black-throated, winter birds have browner upperparts, usually with obvious and extensive white on the face (but juveniles are often dusky-headed). It has a peculiar yet distinctive habit of intermittently raising its head and neck in flight.

Pitfalls If seen well, typical individuals are readily identifiable, but not all are so straightforward. Specific points to remember are: 1 Red-throated not infrequently holds its bill horizontally; 2 its head shape may, in certain postures, appear more angular; 3 in certain lights the upperparts can look very dark and contrast markedly with the underparts (provoking confusion with Black-throated) and 4 in certain positions, it can show an isolated white patch on the rear flanks, again suggesting Black-throated. Identification of distant individuals demands caution.

Size, structure and bill Intermediate in size between Red-throated and Great Northern (but measurements overlap with both). Very sleek, streamlined and graceful, but fuller-breasted than Red-throated. Unlike Great Northern, the head is gently, smoothly and evenly rounded, although in certain postures it can show a more abrupt forehead. The bill is usually held horizontally (occasionally at an upward angle) and is slender, pointed and straight, with the upper mandible gently downcurved towards the tip; the shape, however, is variable, some being slightly thicker-billed. The bill is grey with a dark culmen and cutting edges (less obvious than on Great Northern) but it blackens towards spring.

Plumage A crisply clean, almost auk-like black-and-white diver. The dark of the head is tinged velvety grey at close range (in late spring they can look quite grey-headed) but they usually look strikingly black and white, with a sharp and even line of demarcation running below the eye and down the middle of the neck-sides, thereby producing a larger dark nape area than Red-throated (note that Great Northern is rather dusky about the head with a dark half-collar on the sides of the lower neck). The eye-ring is thin so that, unlike most Great Northern, the eye does not stand out within the dark head. The flank pattern is a useful feature: the fore-flanks are blackish but the rear flanks are white, depending on posture often standing out as a distinctive isolated white patch, obvious even at a distance; this can be reduced to a small round spot (Red-throated may show a similar pattern in certain postures, so this feature should not be used in isolation). Juvenile Has noticeable pale mantle and scapular fringes until it moults in the New Year (adult much plainer). After moulting, ageing is less easy but adult (unlike Red-throated) has a complete pre-breeding spring moult, so any Black-throated in active primary moult in spring will be an adult.

In flight Compared to Red-throated, winter birds look much more black and white and tend to look ‘long and straight’ in flight. Note that the feet look long and large (Red-throated has small feet that produce a short, tapered rear end). In spring, white patterning on summer-plumaged scapulars may be surprisingly obvious, even at a distance.

Size, structure and bill A large, heavy, cumbersome diver. Inexperienced observers may confuse it with first-winter Cormorant, but note the latter’s large, full tail as it leaps to dive. Small Great Northerns do occur, provoking confusion with Black-throated, so head structure is important for separation. Great Northern has a large head with a steep forehead (often with a distinct ‘bump’ where the forehead meets the crown), a rather flat crown and another angle where the crown merges into the nape. However, when alarmed or in diving, feather-sleeking may produce a much more streamlined appearance. Its heavy-headed effect accentuates a heavy, deep-based bill, which usually shows a stronger gonydeal angle than Black-throated; the colour is pale grey, with a dark culmen and cutting edges.

Plumage Essentially black and white, but messier-looking than Black-throated, lacking the latter’s smart contrasts: demarcation between the crown/nape and the throat/foreneck/breast is duskier and less clear-cut, showing a dark half-collar on the lower neck with a white indentation above. A pale eye-surround produces a more isolated and more obvious eye than Black-throated. Great Northern shows a long, rather uneven flank line, invisible if the bird sits low in the water. Newly arrived late autumn adults usually retain obvious traces of summer plumage (almost complete on some) and this may persist well into winter. Juvenile Shows prominent pale mantle and scapular fringes, producing a scalloped pattern (adult much plainer). After moulting in mid to late winter, ageing is more difficult, but moulting adults in late winter lose their flight feathers.

In flight Although size may be difficult to judge on distant flying birds, Great Northern usually looks distinctly larger, heavier and significantly more substantial than the two smaller species, with its heavy bill and large feet being prominent. The extensive dark on the head and the dark ‘half-collar’ on the sides of the neck may also be apparent. A useful tip is that, on spring migration, Great Northern Divers in the English Channel invariably fly high to the west towards their Canadian breeding grounds, whereas Red and Black-throated usually fly east towards Scandinavia.

Size, structure and bill A large, heavy diver, slightly bigger than Great Northern, with a thicker and heavier head and neck. It usually shows a distinct ‘lump’ where the forehead meets the forecrown. The bill is large, very long and ivory-coloured, with a straight upper mandible but a prominently uptilted lower (appears almost banana-like); it is usually held upwards, suggesting a gigantic Red-throated. Unlike Great Northern, the bill lacks any dark along the culmen and the distal cutting edges, although dark feathering protrudes into the base of the upper mandible to the nostril. Note: pale-billed Great Northerns occur, but they always show a dark culmen ridge and cutting edges.

Plumage Similar to Great Northern, but the head is rather paler, greyer and duskier (contrasting more with the dark upperparts) and it has a noticeable pale surround to the eye. As with Great Northern, winter adult White-billed often shows traces of white spotting on the upperparts. Juvenile Even duskier-headed than adult, often showing a diffuse dark patch on the ear-coverts (but adults may show a similar dark area); prominent pale mantle and scapular fringes, more pronounced than on juvenile Great Northern.

In flight Identification should be attempted with great caution. Like Great Northern, a large, heavy diver (thick neck and huge feet) but with a whitish ‘upturned banana’ bill. However, bill details are difficult to discern in flight. Summer-plumaged birds are much more distinctive as the whitish bill contrasts with the black head, but beware of Great Northerns looking pale-billed in certain light conditions.

Despite its name, this North American species breeds as far east as Baffin Island and it seems likely that it will to prove to be a fairly regular vagrant here. Very much the North American equivalent of Black-throated Diver. The most important difference is that the flanks are entirely black, lacking Black-throated’s large white patch on the rear flanks. However, since the flank pattern varies according to the bird’s posture, prolonged and careful observation is necessary to confirm this. In direct comparison, size and structural differences are also obvious (although remember that male divers are larger than females). A Cornish adult appeared c. 20% smaller than an accompanying Black-throated, with a shorter and much slimmer ‘stuck-on bill’. It also showed a steeper forehead, a more rounded and blacker head and a more rounded back. Juvenile Pacific, however, has a greyer head with dusky ear- coverts (which are cleaner and whiter on juvenile Black-throated). A black ‘strap-line’ at the juncture of the throat and the upper neck is an important confirmatory feature (but often indistinct or even absent on juveniles). A thick black band (or ‘vent strap’) behind the legs, isolating the white undertail-coverts, may be noted, but this can also be shown by some Black-throated (as this is below the surface of the water, the bird will need to be seen rolling onto its side). For further information see Mather (2010).

References Appleby et al. (1986), Burn & Mather (1974), Mather (2010).