Chapter One

There's Nothing New in Trading

Nihil sub sole (there is nothing new under the sun)

Ecclesiastes 1:9

Let me start if I may with a book I have read, many, many times, and was the 'course book' recommended to us by Albert as we sat, innocent and expectant on that first morning, clutching this book in our hands.

The book in question was Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, written by Edwin Lefevre and published in 1923. It is an autobiography of one of the iconic traders of the past, Jesse Livermore, and is as relevant today, as it was then. But one quote in particular stands out for me, and it is this:

“there is nothing new in Wall Street. There can't be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market today has happened before and will happen again”

This in essence sums up volume, and Volume Price Analysis. If you are expecting some new and exciting approach to trading, you will be disappointed. The foundations of Volume Price Analysis are so deeply rooted in the financial markets, it is extraordinary to me how few traders accept the logic of what we see every day.

It is a technique which has been around for over 100 years. It was the foundation stone on which huge personal fortunes were created, and iconic institutions built.

Now at this point you may be asking yourself three questions:

- Is volume still relevant today?

- Is it relevant to the market I trade?

- Can it be applied to all trading and investing strategies?

Let me try to answer the first if I can with an extract from Stocks and Commodities magazine. The following quote was by David Penn, a staff writer at the time for the magazine, who wrote the following about Wyckoff in an article in 2002:

“Many of Wyckoff’s basic tenets have become de facto standards of technical analysis: The concepts of accumulation/distribution and the supremacy of price and volume in determining stock price movement are examples.”

The second question, I can only answer from a personal perspective.

I began my own trading career in the futures market trading indices. From there I moved to the cash markets for investing, commodities for speculating, and finally into the currency markets in both futures and spot. In all of these, I have used volume and price as my primary analytical approach to each of these markets, even spot forex. And yes, there is volume in forex as well. Volume Price Analysis can be applied to each and every market. The approach is universal. Once learnt you will be able to apply this methodology to any time frame and to every instrument.

Finally, the best way to answer the third question of whether Volume Price Analysis can be applied to all trading and investing strategies, is with a quotation from Richard Wyckoff who, as you will discover shortly, is the founding father of Volume Price Analysis. He wrote the following in his book 'Studies in Tape Reading':

“In judging the market by its own actions, it is unimportant whether you are endeavoring to forecast the next small half hourly swing, or the trend for the next two or three weeks. The same indications as to price, volume, activity, support, and pressure are exhibited in the preparation for both. The same elements will be found in a drop of water as in the ocean, and vice versa”

So the simple truth is this. Regardless of whether you are scalping as a speculator in stocks, bonds, currencies and equities, or you are trend, swing, or position trader in these markets or investing for the longer term, the techniques you will discover here are as valid today as they were almost 100 years ago. The only proviso is that we have price and volume on the same chart.

For this powerful technique we have to thank the great traders of the last century, who laid the foundations of what we call technical analysis today. Iconic names such as Charles Dow, founder of the Dow Jones, Dow Theory and the Wall Street Journal, and generally referred to as the grandfather of technical analysis.

One of Dow's principle beliefs was that volume confirmed trends in price. He maintained if a price was moving on low volume, then there could be many different reasons. However, when a price move was associated with high or rising volume, then he believed this was a valid move. If the price continued moving in one direction, and with associated supporting volume, this was the signal of the start of a trend.

From this basic principle, Charles Dow then extended and developed this idea to the three principle stages of a trend. He defined the first stage of a bullish trend as, ‘the accumulation phase’, the starting point for any trend higher. He called the second stage ‘the public participation phase’ which could be considered the technical trend following stage. This was usually the longest of the three phases. Finally, he identified the third stage, which he called ‘the distribution phase’. This would typically see investors rushing into the market, terrified they were missing out on a golden opportunity.

Whilst the public were happily buying, what Charles Dow called ‘the smart money’, were doing the exact opposite, and selling. The smart money was taking its profits and selling to an increasingly eager public. And all of this buying and selling activity could all be seen through the prism of volume.

Charles Dow himself, never published any formal works on his approach to trading and investing, preferring to publish his thoughts and ideas in the embryonic Wall Street Journal. It was only after his death in 1902 that his work was collated and published, first by close friend and colleague Sam Nelson, and later by William Hamilton. The book published in 1903, entitled The ABC of Stock Speculation was the first to use the term 'Dow Theory', a hook on which to hang the great man's ideas.

Whilst volume was one of the central tenets of his approach to the market, and consequent validation of the associated price action, it was the development of the idea of trends, which was one of the driving principle for Charles Dow. The other was the concept of indices to give investors an alternative view of the fundamentals of market behaviour with which to validate price. This was the reason he developed the various indices such as the Dow Jones Transportation Index, to provide a benchmark against which ‘related industrial sectors’ could provide a view of the broader economy.

After all, if the economy were strong, then this would be reflected in the performance of companies in different sectors of the market. An early exponent of cross market analysis if you like.

If Charles Dow was the founding father of technical analysis, it was a contemporary of his, Richard Wyckoff, who could be considered to be the founding father of volume and price analysis, and who created the building blocks of the methodology that we use today.

Wyckoff was a contemporary of Dow, and started work on Wall Street as a stock runner at the age of 15 in 1888, at much the same time as Dow was launching his first edition of the Wall Street Journal. By the time he was 25 he had made enough money from his trading to open his own brokerage office. Unusually, not with the primary goal of making more money for himself (which he did), but as an educator and source of unbiased information for the small investor. This was a tenet throughout this life, and unlike Charles Dow, Wyckoff was a prolific writer and publisher.

His seminal work, The Richard Wyckoff Method of Trading and Investing in Stocks, first published in the early 1930’s, as a correspondence course, remains the blueprint which all Wall Street investment banks still use today. It is essentially a course of instruction, and although hard to find, is still available in a hard copy version from vintage booksellers.

Throughout his life, Wyckoff was always keen to ensure that the self directed investor was given an insight into how the markets actually worked, and in 1907 launched a hugely successful monthly magazine called The Ticker, later merged into The Magazine of Wall Street, which became even more popular. One of the many reasons for this was his view of the market and market behaviour. First, he firmly believed that to be successful you needed to do you own technical analysis, and ignore the views of the ‘so called’ experts and the financial media. Second, he believed this approach was an art, and not a science.

The message Wyckoff relayed to his readers, and to those who attended his courses and seminars was a simple one. Through his years of studying the markets and in working on Wall Street he believed prices moved on the basic economic principle of supply and demand, and that by observing the price volume relationship, it was possible to forecast future market direction.

Like Charles Dow and Jesse Livermore, who Wyckoff interviewed many times and subsequently published in the Magazine of Wall Street, all these greats from the past, had one thing in common. They all used the ticker tape, as the source of their inspiration, revealing as it did, the basic laws of supply and demand with price, volume, time and trend at its heart.

From his work, Wyckoff detailed three basic laws.

1.The Law of Supply and Demand

This was his first and basic law, borne out of his experience as a broker with a detailed inside knowledge of how the markets react to the ongoing battle of price action, minute by minute and bar by bar. When demand is greater than supply, then prices will rise to meet this demand, and conversely when supply is greater than demand then prices will fall, with the over supply being absorbed as a result.

Consider the winter sales as a simple example. Prices fall and the buyers come in to absorb over supply.

2.The Law of Cause and Effect

The second law states that in order to have an effect, you must first have a cause, and furthermore, the effect will be in direct proportion to the cause. In other words, a small amount of volume activity will only result in a small reaction in price. This law is applied to a number of price bars and will dictate the extent of any subsequent trend. If the cause is large, then the effect will be large also. If the cause is small, then the effect will be small.

The simplest analogy here is of a wave at sea. A large wave hitting a vessel will see the ship roll violently, whereas a small wave would have little or no effect.

3.The Law of Effort vs Result

This is Wyckoff's third law which is similar to Newton's third law of physics. Every action must have an equal and opposite reaction. In other words, the price action on the chart must reflect the volume action below. The two should always be in harmony with one another, with the effort (which is the volume) seen as the result (which is the consequent price action). This is where, as Wyckoff taught, we start to analyse each price bar, using a ‘forensic approach’, to discover whether this law has been maintained. If it has, then the market is behaving as it should, and we can continue our analysis on the following bar. If not, and there is an anomaly, then we need to discover why, and just like a crime scene investigator, establish the reasons.

The Ticker described Wyckoff's approach perfectly. Throughout his twenty years of studying the markets, and talking to other great traders such as Jesse Livermore and J P Morgan, he had become one of the leading exponents of tape reading, and which subsequently formed the basis of his methodology and analysis. In 1910, he wrote what is still considered to be the most authoritative book on tape reading entitled, Studies in Tape Reading, not published under his own name, but using the pseudonym Rollo Tape.

Livermore too was an arch exponent of tape reading, and is another of the all time legends of Wall Street. He began his trading career when he was 15, working as a quotation board boy calling out the latest prices from the ticker tape. These were then posted on the boards in the brokerage office of Paine and Webber where he worked. Whilst the job itself was boring, the young Jesse soon began to realise that the constant stream of prices, coupled with buy and sell orders was actually revealing a story. The tape was talking to him, and revealing the inner most secrets of the market.

He began to notice that when a stock price behaved in a certain way with the buying and selling, then a significant price move was on the way. Armed with this knowledge, Livermore left the brokerage office and began to trade full time, using his intimate knowledge of the ticker tape. Within 2 years he had turned $1000 into $20,000, a huge sum in those days, and by the time he was 21, this had become $200,000, earning him the nickname of the 'Boy Plunger'

From stocks he moved into commodities, where even larger sums followed, and despite a roller coaster ride, where he made and lost several million dollars, his fame was cemented in history with his short selling in two major market crashes. The first was in 1907, where he made over $3 million dollars. However, this gain was dwarfed in the Wall Street crash of 1929, where conservative estimates suggest he made around $100 million dollars. Whilst others suffered and lost everything, Jesse Livermore prospered, and at the time was vilified in the press and made a public scapegoat. No surprise given the tragedies that befell many.

Livermore's own wife assumed they had lost everything again, and had removed all the furniture and her jewelery from their 23 bedroom house, fearing the arrival of the bailiffs at any moment. It was only when he arrived home from his office that evening, he calmly announced to her that in fact this had been his most profitable day of trading, ever.

For these iconic traders, the ticker tape was their window on the world of the financial markets. Wyckoff himself referred to the ticker tape as a :-

"method for forecasting from what appears on the tape now

, what is likely to happen in the future

"

He then went on to say later in ‘Studies in Tape Reading’ :-

" Tape Reading is rapid-fire horse sense. Its object is to determine whether stocks are being accumulated or distributed, marked up or down, or whether they are neglected by the large interests. The Tape Reader aims to make deductions from each succeeding transaction – every shift of the market kaleidoscope; to grasp a new situation, force it, lightning-like, through the weighing machine of the brain, and to reach a decision which can be acted upon with coolness and precision. It is gauging the momentary supply and demand in particular stocks and in the whole market, comparing the forces behind each and their relationship, each to the other and to all."

"A Tape Reader is like the manager of a department store; into his office are poured hundreds of reports of sales made by various departments. He notes the general trend of business – whether demand is heavy or light throughout the store – but lends special attention to the lines in which demand is abnormally strong or weak. When he finds difficulty in keeping his shelves full in a certain department, he instructs his buyers, and they increase their buying orders; when certain goods do not move he knows there is little demand ( market ) for then, therefore he lowers his prices as an inducement to possible purchasers."

As traders, surely this is all we need to know.

Originally developed in the mid 1860's as a telegraphic system for communicating using Morse code, the technology was adapted to provide a system for communicating stock prices and order flow.

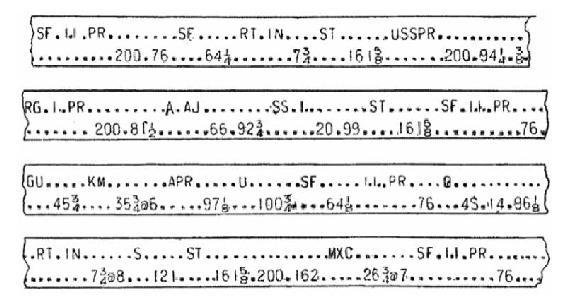

These then appeared on a narrow paper tape which punched out the numbers throughout the trading day. Below is an original example of what these great traders would have used to make their fortunes.

Hard to believe perhaps, but what appears here is virtually all you need to know as a trader to succeed, once you understand the volume, price, trend and time relationship.

Fig 1.10

Example Of Ticker Tape

Fig 1.10 is a Public Domain image from the Work of Wall Street by Sereno S. Pratt ( 1909 ) - courtesy of HathiTrust

www://www.hathitrust.org/

This is precisely what Charles Dow, Jesse Livermore, Richard Wyckoff, J P Morgan, and other iconic traders would have seen, every day in their offices. The ticker tape, constantly clattering out its messages of market prices and reactions to the buying and selling, the supply and demand.

All the information was entered at the exchanges by hand, and then distributed to the ticker tape machines in the various brokerage offices. A short hand code was developed over the years, to try to keep the details as brief as possible, but also communicate all the detailed information required.

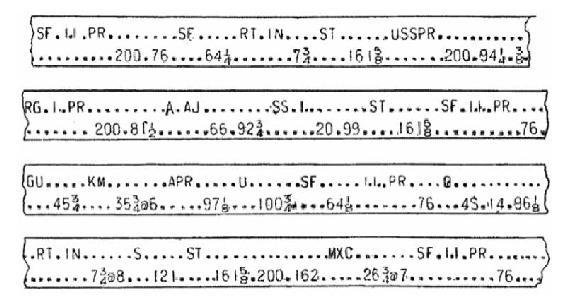

Fig 1.11 is perhaps the most famous, or infamous example of the ticker tape, from the morning of the 29th October 1929, the start of the Wall Street crash.

Fig 1.11

Ticker Tape Of Wall Street Crash

On the top line is the stock ticker, with companies such as Goodyear Tyre (GT), United States Steel (X), Radio Corporation (R) and Westinghouse Electric (WX), with the notation PR alongside to show where the stock being sold was Preferred, rather than Common stock.

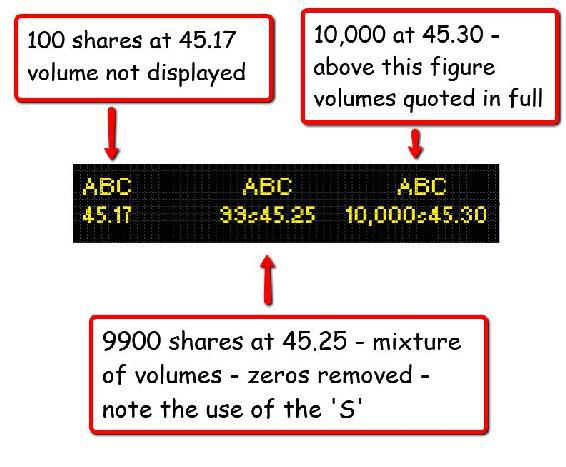

Below on the second line were printed all the prices and trading volumes, all in a short hand form to try to speed up the process. The character ‘S’ was often used in the prices quoted, to show a break between the number of shares being traded and the price quoted, but having the same meaning as a dot on the tape. Where ‘SS’ appeared, then this referred to an odd number of shares, generally less than 100. Finally, zeros were frequently left off quotes, once again for speed. So if we take US Steel (X) as an example from the above we can see on the first line of the ticker tape 10,000 shares at 185 ¾ and by the time we reach the end of the tape, the stock is being quoted as 2.5 ½. So 200 shares, but on such a day, was the price still 185, or had it fallen to 175 or even 165, as many shares did.

This then was the tape all these iconic traders came to know and understand intimately. Once they had learnt the language of the ticker, the tape had a story to tell, and one simply based on price and volume. For their longer term analysis they would then transfer all this information across to a chart.

What has changed since? The honest answer is actually very little.

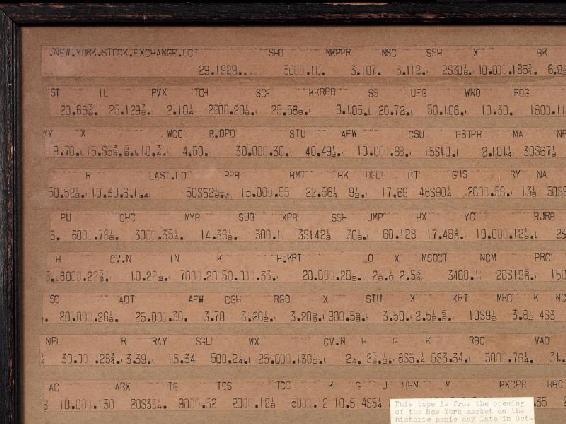

We are fortunate in that our charts are electronic. All the price action and volume is delivered to us second by second, tick by tick, but just to prove that the ticker and its significance still remain, below is a more modern version of the same thing. The only difference is this is electronic, but the information it portrays is the same.

Fig 1.12

An Electronic Ticker

Looks familiar doesn't it? And what do we see here in this very simple example in Fig 1.12?

Here we have a price that has risen from 45.17 to 45.30 supported by what appears to be strong volume. What we don't know at this stage is the time between these price changes, and whether the volumes for this instrument are low, above average or high. All key factors.

Whilst the two look similar, there is one HUGE difference, and that was in the timeliness of the information being displayed. For the iconic traders of the past, it is even more extraordinary to think they managed to succeed despite the delays in the data on the ticker tape, which could be anything from a few minutes to a few hours out of date. Today, all the information we see is live, and whether on an electronic ticker, an electronic chart, or in an on screen ticker with level 1 and level 2 data, we are privileged to have an easy life when trading, compared to them.

Finally, in this introduction to volume and price analysis, let me introduce you to another of the trading ‘greats’ who perhaps will be less familiar to you. His legacy is very different to those of Dow, Livermore and Wyckoff, as he was the first to expose, a group he variously referred to as ‘the specialists’, ‘the insiders’ and what perhaps we would refer to as the market makers.

Richard Ney was born in 1916, and after an initial career in Hollywood, transitioned to become a renowned investor, trader and author, who exposed the inner workings of the stock market, as well as the tacit agreements between the regulatory authorities, the government, the exchanges and the banks, which allowed this to continue. In this respect he was similar to Wyckoff, and as an educator saw his role of trying to help the small investor understand how the game was rigged on the inside.

His first book, The Wall Street Jungle was a New York Times best seller in 1970, and he followed this up with two others, The Wall Street Gang and Making It In The Market. All had the same underlying theme, and to give you a flavour let me quote from the forward by Senator Lee Metcalf to The Wall Street Gang:-

“In his chapter on the SEC Mr Ney demonstrates an understanding of the esoteric operations of the Stock Exchange. Operations are controlled for the benefits of the insiders who have the special information and the clout to profit from all sorts of transactions, regardless of the actual value of the stock traded. The investor is left out or is an extraneous factor. The actual value of the listed stock is irrelevant. The name of the game is manipulation.”

Remember, this is a Senator of the day, writing a forward to this book. No wonder Richard Ney was considered a champion of the people.

His books are still available today and just as relevant. Why? Because everything that Richard Ney exposed in his books, still goes on today, in every market, and let me say here and now, I am not writing from the standpoint of a conspiracy theorist. I am merely stating a fact of trading life. Every market we either trade or invest in is manipulated in one way or another. Whether covertly by the market makers in equities, or in forex by the central banks who intervene regularly and in some cases very publicly.

However, there is one activity the insiders cannot hide and that is volume, which is why you are reading this book. Volume reveals activity. Volume reveals the truth behind the price action. Volume validates price.

Let me give you one final quote from The Wall Street Gang, which I hope will make the point, and also lead us neatly into the next chapter. From the chapter entitled “The Specialist's Use of the Short Sale”, Richard Ney says the following:-

“To understand the specialists' practices, the investor must learn to think of specialists as merchants who want to sell an inventory of stock at retail price levels. When they clear their shelves of their inventory they will seek to employ their profits to buy more merchandise at wholesale price levels. Once we grasp this concept we are ready to posit eight laws:

- As merchants, specialists will expect to sell at retail what they have bought at wholesale.

- The longer the specialists remain in business, the more money they will accumulate to buy stock at wholesale, which they will then want to sell at retail.

- The expansion of communications media will bring more people into the market, tending to increase volatility of stock prices as they increase elements of demand-supply.

- In order to buy and sell huge quantities of stock, Exchange members will seek new ways to enhance their sales techniques through use of the mass media.

- In order to employ ever increasing financial resources, specialists will have to effect price declines of ever increasing dimensions in order to shake out enough stock.

- Advances will have to be more dramatic on the upside to attract public interest in order to distribute the ever increasing accumulated inventories.

- The most active stocks will require longer periods of time for their distribution.

- The economy will be subjected to increasingly dramatic breakdowns causing inflation, unemployment, high interest rates and shortages of raw materials.

So wrote Richard Ney, who correctly called consecutive market tops and bottoms throughout the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s. He was the scourge of the SEC, and the champion of the small speculator and investor.

Therefore, volume reveals the truth behind the numbers. Whether you are trading in manipulated markets such as stocks or forex, or ones such as futures where we are dealing with the major operators, volume reveals the manipulation and order flow in stark detail.

The market makers in stocks cannot hide, the major banks who set exchange rates for the foreign exchange markets, cannot hide. In the futures markets, which is a pure market, volume validates price and gives us a picture of supply and demand coupled with sentiment and the flow of orders as the large operators move in and out of the markets.

In the next chapter we are going to look at volume in more detail, but I am going to start with an article I wrote for Stocks and Commodities magazine, many years ago, and which echoes the eight laws of Richard Ney. It was written long before I came across Richard and his books, but the analogy is much the same and I include it here, to further reinforce the importance of volume in your trading. I hope I am getting the message across, but if not, the following ‘parable’ may convince you. I hope so.