|

“FALLEN INTO THE HANDS OF HARD MEN IN AN EVIL HOUR” The Lynching of Baxter |

5 |

John McCannon of Frying Pan Gulch1 regarded himself as a leader of men. It was an opinion that may well have been justified. When he first appears in the historical record of Colorado Territory he already seems to have carried the title Captain, a rank he may have earned while supporting the antislavery side in the “Bleeding Kansas” troubles before coming west; he had served as quartermaster for the Kansas Free State Militia.2 Or it may be that the men who later wrote about his activities during 1863 conferred on him retroactively a rank he did not actually earn until the following year when, in November 1864, as a captain in the Third Colorado Regiment, he participated with unapologetic relish in what came to be known as the Sand Creek Massacre of a peaceful band of Cheyenne Indians.3

Whether he bore the title before April 1863 may be uncertain; what is sure is that he became a captain, if not a military one, shortly after the news of the murders of Fred Lehman and Sol Seyga made its way over the Snowy Range into California Gulch, where he and others were trying to eke their fortunes in gold out of the heavy red sands and stubborn granite boulders and black rock that—ironically, had anybody known it—actually concealed an unimaginable bonanza of silver that would not be discovered for another fourteen years and finally give birth to the boomtown of Leadville.

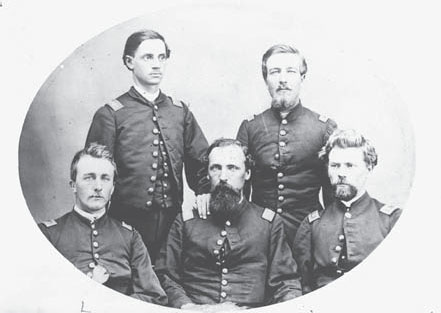

McCannon must have offered a commanding presence. Certainly his letters, preserved in the files of the Kansas Historical Society, are full of a brash, self-assured belligerence.4 His 1864 photograph shows a high-cheekboned, dark-browed countenance with a lofty forehead and pale, penetrating eyes; the mouth and chin are concealed behind a thicket of mustache and chin-whiskers. Three upper buttons of his military tunic are undone, the better to slip a hand into his bosom, Napoleon-like, but on the occasion of having his likeness taken he has restrained himself from actually making the gesture, almost as if he senses it would look absurd and he has no desire to risk making such an obvious impression of vanity.5 It is tempting to call his appearance hard and uncompromising, but that might be a reading not so much of his physical being as of what we know he did, and caused to be done.

On April 28 two men from Mosquito arrived in California Gulch to report that Lehman and Seyga had been cruelly slain in South Park and, according to a Rocky Mountain News Weekly correspondent in Oro City, “to request us to send out a sufficient force to cooperate with parties from Mosquito and Buckskin Joe, in pursuit of the murderers.”6

A meeting was called in Oro City at White’s Hall,7 in McCannon’s words, “for the purpose of raising men and funds to ferret out and bring to speedy justice the murderers of their comrades.”8 Resolutions were passed to raise a company of volunteers and to defray its costs. McCannon himself, in a later reminiscence, names seventeen fellows who volunteered to make up the avenging party, putting his own name at the end of the list. “The last-named,” he modestly wrote, “was selected as Captain of the company.”9

Just then California Gulch was playing out. In the fall of 1860, at the height of the rush into the then-new diggings, 10,000 men were estimated to have swarmed the place.10 However, “after the first year of the gold excitement the population decreased so rapidly that, in 1866, there were but 150 permanent residents.”11 But if the allure of the gulch was fading, the nature of the miners who stubbornly kept picking away at its scant remnants of color had not softened one whit. As an early historian wrote:

[T]here was so little of the ordinary work of a public character to be performed that the officers found little to do and were not particular whether that was done or not, as the inhabitants were of that class of men, who, if they wanted anything done for their own convenience, did it, and saved themselves the trouble of going through the formula of legal authority.12

Such appears to have been the attitude of McCannon’s posse. Not only could they requite the tragic loss of their neighbors, the task offered the agreeable diversion of sport—hunting down murderers looked far more satisfying than continuing to toil in the increasingly unrewarding gulch. One of the stalwarts, Joseph M. Lamb, recalled in later life how, if there were killers abroad in the land, “the camp thought it was time to take up killing also.” To this end, “the party was supplied with a complete outfit by public spirited citizens. It was decided to travel afoot, owing to the rough nature of the country, and to carry bedding and food on pack animals.”13 Lamb himself “shouldered a trusty double barrel gun.”14 The decision to travel by shank’s mare rather than on horseback sounds counterintuitive, but two different sources confirm it,15 and, surprisingly, the strange-seeming choice proved a productive one.

McCannon and his posse crossed Weston Pass into South Park on April 29.16 Before setting out, McCannon had sent a man to Cache Creek17 “to get Alexander Morse18 to join me at Weston’s ranch, and to bring some pack-animals with him, and to cross the range that day or night at all hazards.” Morse complied, and brought with him to Weston’s ranch four more men eager to join in the hunt.19

At Philo Weston’s wayhouse McCannon expected to meet the promised contingents from Buckskin Joe and Mosquito but

when I got there, to my surprise, ten men only presented themselves, and they were sent by one N.J. Bond, of Buckskin Joe … without pack animals, provisions or money, and with the request that we furnish them provisions and animals; this I had no right to do, and should not have done so if I had. The Buckskin Joe delegation then returned home [leaving us] to our own resources.20

The McCannon party “laid over one day at Weston’s ranch, while I [McCannon], with a team, went to Fairplay for a supply of provisions.”21 Here McCannon found some troopers of Colorado Cavalry, queried them, and determined they had little to offer save conjecture regarding the identity or whereabouts of the killers. “Nothing authentic could be ascertained,” he curtly concluded.22

Private Ostrander’s diary notes that Lehman and Seyga (Vinton?) were buried in the Fairplay cemetery on April 29.23 McCannon had crossed the Snowy Range that morning and Fairplay lay only four or five miles distant from Weston’s, so it is possible he may have been present for the interment and gained from that sad event an additional incentive to deal out rough justice to the killers. What is certain is that while in Fairplay he encountered four more men, one of whom was Charles Carter, the bereaved brother of Bill Carter,24 who “were on the same errand—looking up the foulest of the most foul perpetrators of crime.” Carter and his companions joined the California Gulch posse at Weston’s ranch.25

Now Captain McCannon made a consequential decision. “I sent seven mounted men in a northerly direction to clean out a gang of known thieves [emphasis added] and to scour the country to the northeast.”26 Up to this moment his announced intention—indeed, his principal mission as given him by the Oro City committee—had been to find the murderers of Lehman and Seyga, though it is true the chairman of that body, one Captain S. D. Breece, had, in his opening remarks at the public meeting, “drawn particular attention to the numerous murders and robberies … lately committed in the South Park.”27 Clearly common thievery should have taken second place to serial murder, but in view of what was to come, it is possible McCannon and his compatriots may have thought they had reason to treat the two crimes as one.

The names of the seven vigilantes McCannon sent north are worth recording. C. T. Wilson was “Commandant.” The others were Alexander Morse of Cache Creek, William R. McComb, J. A. Hamilton, John Brown, John J. Spaulding, and a Doctor Bell.28 Private Ostrander seems to have encountered them on April 30 and his account tells us something of their temper:

Five or six citizens went on the … trail this morning. They wanted some of our horses for packing. Would not have the ponies, said they wanted good horses or none. Had not sence [sic] enough to know that the ponies were the best. Thought things were at a pretty pass when government horses could not be had for such a purpose.29

In his reminiscence McCannon goes on to relate that “Commandant” Wilson’s impatient party “succeeded in capturing some of the gang.” In his near-contemporary report to the Oro City committee he said this group “did good service in routing a den of thieves.”30 What gang? What thieves? What about the killers of Lehman and Seyga? Without explaining further, he next writes dismissively, “One Baxter was hung by some recruits of the Second [sic] Colorado Regiment near Fairplay.”

Who was Baxter? Why was he lynched? We will not learn that from John McCannon. For something approaching the truth we must turn from him to other sources having less to hide—though it must be borne in mind that whatever we do, we can come no nearer than what some historians have called rhetorical or subjective truth. Multiple narratives exist and no two agree in all respects. But if each account must be considered with caution, each also contains some elements of fact, some of supposition, some of rumor, and even one or two of deliberate evasion, and we must weigh all these factors before we guess—for guess is all we can do—what might have happened. Each version must also be studied with an eye toward its proximity to the event in time, allowing for the distortion of memory over the passing years.

One account, for instance, comes to us at first hand, within four days of the incident, and explicitly links “Commandant” Wilson’s California Gulch detachment—not the soldiers—with the lynching. A Mr. Richards, identified as the postmaster at Parkville,31 told the Rocky Mountain News Weekly that on May 2, while he was staying at the Kenosha House, Hamilton and Spaulding of Wilson’s group “rode up and asked for an assisting party to return with them to Snyder’s ranch … for the purpose of arresting a man named Baxter who was supposed to be there secreted.”32

The two possemen said they and five others had stopped by the ranch “for the purpose of warming themselves,” only to be denied entry by Mrs. Snyder under circumstances the possemen found suspicious—she claimed to be alone but some of Wilson’s men heard the clumping of heavy boots within and, “as they were in quest of Baxter, they began to feel he was there concealed.” Why was Baxter known by name? Who had named him? Why was he sought? By this time Metcalf’s and Allen’s description of the murderers as Mexicans or blacks must have been widely known. Was Baxter of dark coloring? We do not know the answers to any of these questions. All we know is that Wilson’s men were intent on laying hold of him. They persisted in their appeals to Mrs. Snyder to admit them, and during this parley someone inside the house fired two shots through a window “into the crowd outside,” killing a mule belonging to the posse.

At this point the seven members of Wilson’s detachment withdrew to a distance, conferred, and uncertain how many armed inmates of Snyder’s house they might be confronting, agreed to send Spaulding and Hamilton to the Kenosha House for reinforcements. Postmaster Richards and six other men who were staying at the hostelry responded at once, “and in an hour the party, increased to fourteen, again came forward and demanded admission at Snyder’s.”

Richards was an acquaintance of Snyder and eventually persuaded the terrified rancher to come out, “pushing his wife in front of him as a living shield against a fire which he feared might be opened upon him.” Richards then glimpsed a man inside the house, heard the clicking of a cocked gun, got the drop on the fellow, and demanded and obtained his surrender. This proved to be the much-sought-after Baxter. Richards’s story continues:

[Baxter] and Snyder were then taken to the Kenosha House, where both were subjected to three or four successive hangings by the neck, in the hope to obtain something from them by confession. Nothing, however, was elicited, farther than a confirmation of what was generally believed, that Snyder and Baxter were both bad characters. Baxter confessed to having escaped from the sheriff of Park county five or six weeks ago.

Snyder was given twenty-four hours to leave the country, and Baxter was taken up and delivered to the miners of California Gulch, to be dealt with as they might see fit.33

Our next source is the Reverend John L. Dyer, the savior of poor John Foster.34 Though Dyer wrote in the 1890s, his memory—and his conscience—were clear, and his description of what the California Gulch posse saw fit to do was unsparing. At about the time of the burials of the victims at Fairplay, he recalled, word came “that a man was harbored at a ranch some fifteen miles east, and a company went over about night and demanded him.” Dyer confirms in broad outline Postmaster Richards’s description of the various attempts by “Commandant” Wilson’s squad of McCannon’s posse to gain admittance to the house, the shots that killed the mule, and the withdrawal of the besiegers to wait for morning.

At sunup, Dyer writes, the posse—or, more properly, the mob—gave the inmates of the house “just a few minutes to surrender the man, under the alternative of having the house burned.” This threat sufficiently cowed those within to open up, and the mob rushed in, captured the stranger, forced the ranchman to pay for the dead mule, and ordered him to leave his own home.35

They took the prisoner near to Fairplay, and without trial or jury, hanged him, although he denied being guilty of any crime for which he deserved death. But poor Baxter had fallen into the hands of hard men in an evil hour. This was a mob, and nothing better ever comes of such work.36

Next we consider the account of “Dornick,” the stringer for the Weekly Commonwealth, replete with faux-Latinate puns and bursting with ghoulish glee. It is worth repeating in its repellent entirety:

From Dornick,

May 8th, 1863

I have the pleasure of informing you that one of the notorious jayhawkers has been captured, and like

“Zachariah he

Clum a tree.”

“his lord and master (the devil) for to see,” and is now non est, up a limb-i-bus, neck in rope-i-bus, et dangling in the air-i-bus. On last Saturday evening some citizens got on the track, as they had reason to think, of suspicious characters, and went to Snyder’s Ranch in the Park at the junction of the Tarryall and Jefferson roads, and when they attempted to enter the house were denied permission by the woman, who told them her husband, Snyder, was away and she was alone. The citizens persisted in entering, and in the act of doing so, were met by several shots fired from within, one of which took effect upon one of the horses at the door, killing it instantly. The party then surrounded the house and guarded it until morning, when they succeeded in entering and corralled Snyder and a man named Baxter, and took them away towards Fairplay and examined them both by a little choking process with a rope to elicit any confession of crime they felt disposed to make under the pressing circumstances. Not much was got out of Snyder who was liberated. Baxter was found to be one of the gang which jayhawked the mules with Leeper, Brown and others last fall, from the Lehman brothers at Frying-pan gulch. He also had on him a coat which was identified as that worn by Carter, who was shot at the Cottage Grove, Baxter himself acknowledged it to be Carter’s coat. In his pocket were found some bullets which corresponded with those found in several of the murdered bodies, in size, weight and a peculiar mark made by the moulds in moulding. Satisfied of his criminality, the citizens delivered him over to the soldiers at Fairplay, who took him out on the road about two miles east of Fairplay, and about noon (Monday) his body might have been seen suspended by a rope to the limb of a tree—no breath of life visible to any great extent in said body. The habeus corpus was suspended; he “struck the cap” and went up the spout, to the place where jayhawkers ought to go. It is some consolation to the friends of Lehman to know that this notorious scoundrel took his last look at this earth in sight of the bloody Red Hill where poor Lehman was murdered. Every one justifies this act, and wishes that more of the same sort may be had to “hang dangling in the air” like the body of the ancient J. Brown. The scouts are on the track of the others and it is hoped the country will soon be rid of these diabolical outlaws.

There are some laughable circumstances growing out of the present excitement to one who has an eye for the ridiculous side of things. For instance, while every one when going a mile from his own door is watching on all sides for outlaws, two neighbors meet at a distance; they approach each other cautiously and fail to recognize each other; one stops to reconnoiter, and the other becomes alarmed; each is certain the other is a jayhawker, and both crouch down and run dodging in opposite directions as if the Old Harry was after them and report having narrowly escaped at the hands of a villain.

Since the life of Metcalf was saved by the public document in his pocket, in which the ball that was fired at him lodged, everybody is practicing on pamphlet targets, and no one goes from home now, without arming himself with a double-barrelled shot gun, loaded with buck shot, three or four of Bennett’s documents in each vest pocket, and a bottle of schnapps in case of a truce.

Ever, DORNICK37

Here at last, buried in Dornick’s sardonic prose, we catch a glimpse of a reason for the otherwise inexplicable fury of the mob against Baxter and their haste to execute him. The correspondent wrote, “Baxter was found to be one of the gang which jayhawked the mules with Leeper, Brown and others last fall, from the Lehman brothers at Frying-pan gulch.” How and when this discovery was made is not disclosed. But we do know that Baxter was being sought, by name, at the time “Commandant” Wilson’s vigilantes first approached the Snyder ranch. Why were they looking for this particular man?

An intriguing possibility is that even before McCannon’s party left California Gulch, a man named Baxter was thought to have been a member of the Leeper mule-rustling band and was suspected of lurking about South Park—hence, Breece’s instructions to McCannon that “particular attention” be paid to the “numerous murders and robberies … lately committed.” But why would Baxter’s presumed association with robberies in general or with the “Leeper gang” in particular have implied a link to the murders of Lehman and Seyga?

We have seen in Chapter 4 how Lehman, at the time of his death, was returning from US District Court in Central City where he had testified against several of the suspected mule rustlers38—George W. Brown, Isaac Roberts, Jonathan Leeper, and two men named Slatten and Harrison, whose first names were unknown to the grand jurors who indicted them. Baxter’s name does not appear among those indicted. Whatever the reason, there is a high probability that “Commandant” Wilson’s mob believed Baxter to be an associate of the Leeper crowd if not one of the five indicted.

The extant court records are incomplete as to the trial verdicts in the cases of Roberts, Leeper, Slatten, and Harrison. It is possible one or more of these men were exonerated. But the records do show that Brown was found guilty, largely on the basis of Lehman’s testimony and that of his brother, Ernst.39 “Commandant” Wilson’s party must have known this and concluded that Baxter had followed Lehman from Central City to South Park and murdered him at Red Hill Pass in revenge for his damaging testimony against Brown. This gives new emphasis to Dornick’s assertion, “It is some consolation to the friends of Lehman to know that this notorious scoundrel took his last look at this earth in sight of the bloody Red Hill where poor Lehman was murdered.”

While all this goes to suggest there may have been something of a pretext for the lynching of Baxter in the minds of “Commandant” Wilson’s vigilantes—something beyond simple lynch fever run amok—in the end there was no solid proof of the victim’s complicity in the murder of Lehman, though it may have been true that he had rustled some mules with Leeper and the others. And it cannot be overlooked that rustling, by itself, was often a hanging offense on the frontier. No official records have survived to substantiate Richards’s claim that Baxter had recently escaped from the Park County sheriff or to explain why he was in custody, though as we will see, Ostrander repeats the assertion. But even were it true that Baxter was some sort of criminal, the circumstances of his fate lend the whole affair a foul aftertaste, and it is no surprise that in McCannon’s recollections he gave it short and cryptic shrift.

The charitable Reverend Dyer had drawn a veil over some of the worst of the incident, such as the repeated near-strangling of poor Snyder, a detail “Dornick” so delighted in. There is no telling what effect this treatment had on the unfortunate ranchman; it is worth remembering that Reuben Samuel, the foster father of Jesse James, was subjected to this same treatment in Missouri early in the Civil War, and never fully recovered his mental or physical faculties.40 As regards the nature of Baxter’s crimes, Dyer does not proclaim his entire innocence; he simply tells us the man had done nothing to merit death.

The suspicions of Baxter’s complicity in the deaths of Lehman and Seyga apart, it is hard to know what to make of the incriminating evidence “Dornick” says the mob found on the man, except to adduce the fact that, in a few days’ time, the real murderers would be found, and Baxter would be shown to have been innocent of the South Park killings, whatever else he might have been guilty of. Whether he had ever been a member of “the Leeper Gang” we cannot know.

In one other respect “Dornick’s” report, revolting as it is, shies away, as McCannon’s also does, from the one damning fact that Reverend Dyer was willing to confront: that it was not the disreputable toughs of the First Colorados who hanged Baxter; it was in fact the mob, and very likely “Commandant” Wilson’s mob, which is to say, John McCannon’s mob.41 Private Ostrander saw it all, and what he saw shattered his habitual eerie calm.

His diary entry for May 2 mentions that two prisoners were taken by “the boys, that is, the First Colorados … but they were released an hour after wards.” Next day, a Sunday, “we were just this side of Snider’s with a prisoner by the name of Baxter, who they42 had taken this morning at Snider’s. They went there last night to take them and were fired on from the house, having a mule killed. They watched the house till daylight and then arrested them. I was ordered to go back with the t[w]o men and help guard them.”43

On Monday, May 4, Ostrander’s diary reads as follows:

We stopped at McLaughlin’s last night and left there this morning at nine o’clock, when within a mile of Fairplay we met some of the citizens to whom we delivered the prisoner [emphasis added]. He was known to be an outlaw having escaped mail [jail?] in Dinver [sic] once and from the sheriff once. They took him out in the timber and hung him to a tree. Oh it was a horrible sight to see the poor fellow hung and he was all the time protesting his innocence even to the last breath. But I don’t know but it was justice, for he was undoubtedly an outlaw and all outlaws are dangerous characters now.44

The various versions of Baxter’s fate cannot all be reconciled. But Ostrander’s diary is probably our most unbiased source. He makes it clear that at some point the First Colorado Cavalry had custody of Baxter and that at a later time they handed their prisoner over to the mob. It is a loss to history that he fails to describe why and how this atrocity happened. Unlike many of his messmates, Ostrander seems to have been a reserved and conscientious fellow if remarkably unreflective, and his reticence leaves us in the dark at a critical juncture. The hanging wounded him deeply but he did not see fit to explain precisely how the transfer of the prisoner came about, fraught as that was with dire consequences.

The majority of the Firsters were a hard lot. Already they had shown themselves eager to chase down and lynch John Foster, Reverend Dyer’s parishioner. Hanging, for them, might have seemed an agreeable way to break the monotony of their seemingly endless patrol duty. But even granting that the enlisted men, the rankers, of the “Pet Lambs” were largely a set of ruffians, what of their officers, Lieutenants Wilson and Oster? Did they acquiesce in what happened? Lead it? Withdraw and ignore it? The record does not tell us.

Baxter may not have been the only one to swing. The Rocky Mountain News Weekly, in wrapping up Postmaster Richards’s story, had this to say:

On the return of the [Wilson] party, another suspicious character was arrested, who, after a few administrations of the hangman’s noose around his neck, promised to reveal the hiding place of several of the gang who have been committing outrages in the Park. At the time Mr. Richards left, the party sent out in company with this last prisoner had not returned. It is altogether likely, however, that we shall in a day or two hear of a hanging in the above vicinity. Vengeance will soon overtake the band of cut-throats which has been holding a carnival of blood in the southern and south western parts of this territory.45

The Weekly Commonwealth’s May 14 edition, in a report separate from “Dornick’s,” seems to confirm Richards’s surmise:

We learn from a gentleman just down from the South Park, that three men were lately arrested in that vicinity for being connected with the recent depredations thereabouts, and the gentle but effective arguments of Judge Lynch prevailed over their minds to such an extent that they made confessions which it is hoped will lead to the ferreting out of the whole gang. There is nothing like a few feet of rope, a stout tree and a man’s neck, to bring out the “gab.”46

1. A small gulch draining into Colorado Gulch, which in turn fed what was then known as the West Fork of the Arkansas River. This was a short distance west of the future location of Leadville, Colorado.

2. Territorial Kansas Online—Transcripts, http://www.territorialkansasonline.org/~imlskto/cgi-bin/index.php?SCREEN=show_document&documentid=102477&SCREEN_FROM=show_location&county_id=4 (item no. 102477, call no. James Abbott Collection, Box 2, Folder 11), accessed February 27, 2013.

3. Rocky Mountain News, January 26, 1881, interview with McCannon entitled “Scenes at Sand Creek.”

4. Territorial Kansas Online, http://search.ku.edu/search?q=McCannon&btnG=Search&site=TKO&sort=date%3AD%3AL%3Ad1&output=xml_no_dtd&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&filter=0&client=default_frontend&proxystylesheet=TKO (item no. 6975, call no. James Abbott Collection, Box 2, Folder 11), accessed February 27, 2013.

5. National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/sand/historyculture/people.htm, accessed January 18, 2013.

6. Report dated May 21 in the Rocky Mountain News Weekly, May 28, 1863.

7. Ibid.

8. John McCannon, “An Account by a Participant,” in Captain B. F. Rockafellow, “History of Fremont County,” in Baskin, History of the Arkansas Valley, 576.

9. Ibid. The others named include Joseph M. Lamb, Julius Sanger, McCannon’s brother O. T., Thomas S. Wells, C. F. Wilson, William R. McComb, John Gilbert, Frank Miller, Frederick Fredericks, William Youngh, James Foley, John Landin, Charles Nathrop, John Holtz, John Endleman, and William Woodward. The Rocky Mountain News Weekly report of May 28 says there were eighteen men in the party.

10. R. G. Dill, “History of Lake County,” ibid., 213.

11. Ibid., 208.

12. Ibid.

13. The Denver Daily News, February 24, 1894.

14. Ibid.

15. Weekly Commonwealth, May 21, 1863.

16. Ibid.

17. Located a few miles west of the town of Granite, Cache Creek was the location of one of the first gold deposits discovered along the Arkansas headwaters.

18. Morse’s identity is not known.

19. These were J. A. Hamilton, J. J. Spaulding, John Brown, and a Dr. Bell.

20. Rocky Mountain News Weekly, May 28, 1863.

21. McCannon, “An Account by a Participant,” 576–577.

22. Ibid., 577.

23. Ostrander, This Soldier Life, 18.

24. Ibid. The others were Benjamin Griffith, Charles Low, and “another man.”

25. McCannon, “An Account by a Participant,” 577.

26. Ibid.

27. Rocky Mountain News Weekly, May 28, 1863; emphasis added.

28. Ibid.

29. Ostrander, This Soldier Life, 18.

30. Rocky Mountain News Weekly, May 28, 1863.

31. Seat of neighboring Summit County, 1861–1862.

32. Rocky Mountain News Weekly, May 7, 1863.

33. Ibid.

35. Dyer, The Snow-Shoe Itinerant, 154.

36. Ibid.

37. Weekly Commonwealth, May 14, 1863.

39. Record Group 21, Records of the US District Court of the US Territory of Colorado, Bankruptcy, Civil and Criminal Case Files, 1862–74, Case #54, United States of America vs. George W. Brown, Isaac Roberts, Jonathan Leeper, Slatten and Harrison; Stephen J. Leonard, Lynching in Colorado, 105–106; and Rockafellow, “History of Fremont County,” 580–585, tell of a Jonathan Leeper held in the Denver jail against whom unspecified charges were dropped but who refused to leave his cell because he enjoyed the free meals. Only after a jailer told him a lynching party was on its way to hang him did Leeper flee, only to be shot by soldiers who assumed he had broken jail. It is not known whether this is the same Jonathan Leeper charged in the mule-stealing case.

40. T. J. Stiles, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), 89–91. Leonard, Lynching in Colorado, 97–122, notes that repeated hangings to induce confessions, or simply to inflict torture, were quite common in frontier Colorado. One victim was hanged six times before confessing. Ordinarily those who were repeatedly hanged but later freed seem not to have suffered long-term ill effects but Samuels’s ordeal suggests that lifelong consequences could occur.

41. The Rocky Mountain News Weekly of May 7 also made it plain the First Colorados turned Baxter and Snyder over to “the citizens,” who then tried them “according to the most approved rules of Judge Lynch’s court.” Baxter was recognized and convicted “as an old offender and notorious cattle thief” and was taken “back some two miles on the road between Fairplay and Tarryall, in sight of the bloody red hills, and the next morning his body was found pendant from the limb of a quaking aspen tree.” Ghoulish humor was not lacking in this account either: “Whether he terminated his own existence in that manner, or was aided in ‘shuffling off this mortal coil,’ has not been made know[n].”

42. “They,” in this instance, refers to the citizen mob, as the next lines make clear.

43. Ostrander, This Soldier Life, 19.

44. Ibid.

45. Rocky Mountain News Weekly, May 7, 1863. A tantalizing mystery is the nature of the relationship between the Parkville postmaster Richards and the unfortunate ranchman Snyder. Richards admits they were acquainted, but in the accounts of the time Snyder’s name seems to give off a faintly unsavory odor. Were Snyder and Baxter friends? associates? fellow rustlers? Why was Baxter hiding at Snyder’s? Why was a supposedly reputable postmaster like Richards an acquaintance of Snyder’s?

46. Weekly Commonwealth, May 14, 1863. The lynching of Baxter was also reported as far away as Central City in the Tri-Weekly Miner’s Register of May 9; and B. F. Rockafellow, “History of Fremont County,” in Baskin, History of the Arkansas River Valley, 577, mentions that Baxter was hanged as a member of a gang of horse thieves; cited in Leonard, Lynching in Colorado, 187, note 10.