CHAPTER 4

AMERICAN NEOCLASSICISM AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE SKYSCRAPER (1870–1920)

One might question why this small group of Americans deserves their own chapter. As late-nineteenth century architects, they approached modern architecture with less fervor than their European counterparts. Henry Hobson Richardson, Louis Sullivan, Richard Morris Hunt, and Stanford White practiced with one foot in the past. Their high Victorian gothic and Renaissance revival allusions, use of materials and connection to the development of tall buildings led them ten-tatively toward the modern.

Although Sullivan believed that buildings needed to express their function, he never felt unified with the dedicated revolutions of Adolf Loos or Le Corbusier in Europe. Considered innovative in the design of tall buildings, Sullivan could not refrain from the decorative. He incorporated steel framing but lacked a conceptual expression of the new notion of the skyscraper. America's greatest contribution to the inception of modern architecture was the steel structural system. The historians Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, in their book The International Style, disappointingly describe these architects as the ‘half moderns’ (1996). Unable to fully identify with the neoclassical architects of France, yet incapable of embracing a consistent belief in a modernist ideal, they reside in a moment of transition, at the cusp of a new era.

The sketches of these architects illustrate their unique position and affinity to past styles. Much of their visual expression reflects their education in the beaux-arts tradition. Remarkably poignant, these sketches typify their concerns and beliefs, reflecting the natural world in the case of Louis Sullivan and the stark minimalist essence of the gothic revival with Richardson. Hugh Ferriss’ sketches boldly demonstrate the emotion of the evolving social and political period, heralding the monumentality of the ‘new city’ of tall buildings, while romanticizing the solidity of masonry construction. A brief summary of American architecture at the close of the nineteenth century and the emergence of the skyscraper will set the stage for a discussion of these architect's sketches.

For twenty years following the Civil War, architecture in the United States was mainly classical and gothic. During this period, the country was undergoing an enthusiastic building program including many governmental projects. Described as the second empire baroque, these monumental buildings had strong horizontal layering, mansard roofs and classical elements (Roth, 1979).

The great fire in Chicago in 1871 offered a tremendous opportunity. Burning 1,688 acres of wooden buildings, the need to rebuild was pressing (Douglas, 1996; Charernbhak, 1981). The 1880s were characterized by industrial and technological expansion. Industry was standardizing track gauge, huge corporations were providing electricity, the oil company of John D. Rockefeller was formed, and the emergence of the steel industry provided the materials to construct tall buildings. The small and bounded business district of Chicago produced the commercial building as a type, which quickly spread to New York City. These tall buildings satisfied the need for office space and efficiency in rapidly expanding cities. Contemporary construction of a steel frame clad with a cur-tain wall, the development of elevators and fireproofing, and advancements in environmental con-trol systems, set the stage for the birth of the skyscraper (Goldberger, 1982; Huxtable, 1982).

Regardless of these potential advancements, American architects were still focused stylistically on Europe for direction; thus, the new tall buildings resembled neoclassical or gothic structures stretched in the middle. The first building to demonstrate these qualities and the first true skyscraper was the Home Insurance Building designed by William LeBaron Jenney in Chicago, 1883–1885. Other tall buildings followed including Richardson's Marshall Field Wholesale Store in Chicago, 1885–1887, and Sullivan's Wainwright Building in Missouri, 1890–1891. The architectural critic Paul Goldberger suggests that in Chicago, architects were more interested in structural honesty, while in New York City their concern was the historic appearance of the buildings (1982). Two buildings that predicted a modern approach were the Monadnock Building in Chicago and the Reliance Building, both by Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root. These structures substantially eliminated orna-ment, and the Reliance Building's façade was designed with a large amount of glazing.

The tall buildings of Chicago and New York City were not entirely commercial. Architects such as Hunt were designing tall apartment buildings and for many years the tallest building in New York City was Trinity Church. The wealthy industrialists, desiring vacation homes, initiated a contrasting scale of building in seaside communities such as Newport, Rhode Island. Influenced by Japanese architec-ture, these architects were building wood domestic architecture in the period between 1840 and 1876. Much of this was basically Queen Anne style. Vincent Scully describes this architecture as ‘stick style,’ identified by their rambling asymmetrical shape, large wrapping porches, gabled roofs and, most dis-tinctive, a complex wooden frame and wall surface divided into panels (1955). Richardson expanded this repertoire, using a shingled exterior for his Newport houses from the early 1870s. The shingle style houses, often with recessed porches, were popularized by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White during the 1880s. Many were published in magazines such as Harpers. Additionally published as picturesque sketches in American Architect, two 1880 sketches by Emerson capture the fluid, painterly technique, expressing his design intent. They presented an illusion of modeled light on the shingles. Scully suggests the style of sketching used to represent these buildings by White and Emerson resembles the blurred forms and reflective light of the French impressionist painters.

EDUCATION

American architects were looking to Europe for inspiration. A few of them had traveled to France for education, either at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts or a technical school such as Jenney. The number actu-ally trained abroad were few, as the vast majority were apprenticed with architects influenced by French neoclassicism. William Rotch Ware, editor of American Architect, was an advocate for the neces-sity of architectural schools that would teach precedent. Having attended the Ecole himself, Ware's purpose was ‘to raise the standing of the architectural profession, to draw a sharp line between builders and architects, and to make it clear to the world that the architect was an educated gentleman’ (Scully, 1955, p. 51). He was concerned about the self-educated architect, reflective of the newly formed American Institute of Architects which was established with the role of the professional architect at its foundation. In response, several schools of architecture were formed at this time, the first being Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1868, followed by the University of Illinois (1870), Cornell (1871), Syracuse (1873), University of Pennsylvania (1874) and Columbia (1881) (Roth, 1979). In most cases the system of education in these schools reflected beaux-arts tradition.

The gentleman architect, especially those educated in this system, viewed architecture primarily as an artform and depended heavily on builders’ knowledge of construction and structure. Leland Roth writes concerning the relationship between architect and builder, especially considering the houses of the shingle style: ‘It was then common practice to leave much to the discretion of the contractor, and the clause in building contracts, “to be finished in a workmanlike manner,” expressed what was to builders like the Norcross brothers a sacred duty which they executed with exacting care’ (Roth, p. 167). Architects’ drawings did not include explicit details, so understanding between a builder and an architect were dependent upon reputation and skill. Drawings needed to convey intent, but left much to the contractors’ judgment.

The architects designing tall buildings, however, met with issues of construction and engineering. Several of these innovative architects obtained their education in technical schools or engineering offices. Jenney had received training in engineering at the Ecole Centrale des Arts Manufactures in Paris and Root had studied engineering in New York (Douglas, 1996). Obviously, architects’ offices varied from small to large, but the partners in large architectural firms began to specialize. As Dankmar Adler jovially acquired commissions, Sullivan was concerned with design, especially ornamentation. Similarly, Burnham, with strength in the organizational aspects of architecture, managed the firm while Root was reportedly the design partner (Douglas, 1996). Because the size and scale of his pro-jects were expanding, Richardson terminated drawing and instead sketched his ideas, trusting his draughtsman to the technical drawing. In this way, the sketch, in addition to a personal dialogue, extended its role to intra-office communication. With the popularity of magazines publishing homes of the wealthy, sketches became a mode of advertisement and dissemination of style. As mentioned earlier, these sketches also propagated an emotional atmosphere to promote a style.

MEDIA

In the late nineteenth century, publication in the form of magazines connected the architects of the world. Heavily illustrated, these contemporary ‘pattern books’ transmitted style across the country and between continents. In 1896 Sullivan published his essay ‘The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered’ in Lippincott's magazine. It was this article that delineated the parts of a tall building and likened them to a column, specifying the base, mezzanine, repeated floors/shaft, and the attic col-umn. The proliferation of architectural discourse also widely distributed drawing styles and tech-niques. Many proposed, and completed, buildings were portrayed as sketches to suggest textural or atmospheric impressions.

Although basically similar to previous generations, the tools and materials of this period available to the architect were considerably refined. Paper had been manufactured since the late eighteenth century and could be purchased in large sheets or rolls. The precision of ruling pens and other draw-ing instruments were constantly being improved. Presentation drawings were rendered with ink wash and watercolor. Draughting was precise and detailed using t-squares, triangles, and ruling pens (Hambly, 1988). Sketches relayed information concerning the design of details in the case of Sullivan's carefully explored floral ornament. The initial conceptual musings as illustrated by Richardson's brief sketch resemble a parti diagram describing the essence of the project. A fast and efficient method to visualize, pencil and pen and ink continued to assist in design. With an abundance of architectural and popular periodicals, architects such as Ferriss were able to successfully sway public opinion with their dramatic and emotional visions of the contemporary city. The use of pencil shading to achieve lighting effects made the sketch an atmospheric communication tool. The expansion of urban con-struction helped promote such skills, raising awareness in the minds of Americans that architecture was a factor in the image of the city. The American neoclassical architects depended upon sketches to conceive, envision, and detail their continually more complex building explorations.

Richardson, Henry Hobson (1838–1886)

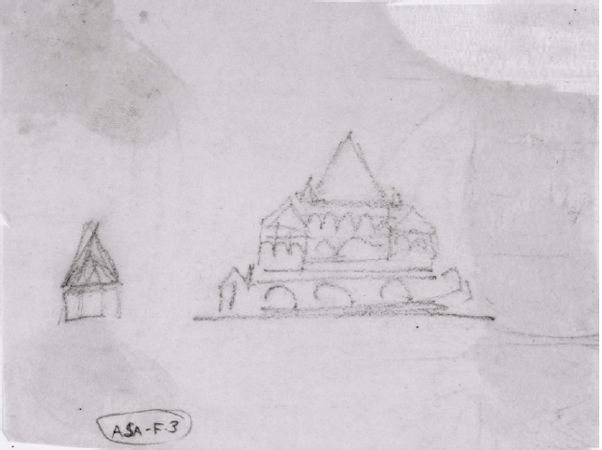

Small sketch from west, preliminary sketch, All Saints Episcopal Cathedral (Albany, NY), 1882–1883, Houghton Library, Harvard College Library, HH Richardson Papers, ASA F3, 10 × 13cm, Graphite on tracing paper

The 1850s produced many high Victorian gothic buildings, and Henry Hobson Richardson's early work reflects this influence. By the early 1870s, Richardson came into his own style, distinguished by heavy masonry and arched entrances, such as two projects in Massachusetts, the Hampden County Courthouse in Springfield and the Thomas Crane Public Library in Quincy. Richardson utilized a creative and individual approach to Romanesque that some describe as eclectic (O'Gorman, 1987). It was this approach that caused his work to be named the ‘Richardsonian Romanesque.’

Richardson was born at Priestly Plantation in St. James Parish, Louisiana, in 1838. He began his higher education at Harvard in 1856 and gained admission to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1860. Following the end of the Civil War, he returned to New York where he received his first independent commission, the Church of the Unity in Springfield, Massachusetts. Upon winning the competition for the design of the Trinity Church, he completed such projects as the Haydon Building, the Cheney Building in Hartford, and those representing his more mature works, the Ames Memorial Library Building at North Easton, Austin Hall at Harvard, and the Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh. After a long illness, Richardson died in 1886 at the age of forty-seven.

This sketch from Richardson's hand (Figure 4.1) expresses his first thoughts for the All Saints Church in Albany, 1882, and acts as a parti for the project. Because of his beaux-arts education, Richardson used a process of design learned from the Ecole in Paris, the esquisse (O'Gorman, 1987). Working on many projects at one time, Richardson would provide small sketches to be given to draftsmen for development. The senior draftsmen knew Richardson's intentions as they drew the designs (Ochsner, 1982). In this way, the sketch represented his concept for the project and communicated it to those in his office.

The project for which this sketch was the impetus was an invited competition designated to be in the gothic style (O'Gorman, 1987). Interestingly, Richardson's early sketch and the final drawing differ quite significantly. The sketch, in elevation, has similarities to his heavy railroad buildings with their massive stone and rounded arches. It displays a distinctive shape comprised of a main peaked roof flanked by two smaller versions. The shape resembles a pyramid, so much so that it may be possible to inscribe a simple equilateral triangle over this building. The technique of the sketch is minimal, using an economy of lines and lacking in detail. The arches in their simplicity consist of a series of ‘m's’ and the lines are mostly singular in weight. The three Roman arches are not perfectly round, but convey enough information so they did not need to be corrected. Very small and brief, the sketch acts an idea diagram and only considers the elevational parti. Although it shows a ground line, the image is lacking in context, another indicator that the sketch is a beginning impression.

In contrast, the competition drawing is an elevation much more reminiscent of the gothic style, although not entirely gothic. The peaked roofs were pared down to resemble spires and the façade has vertical windows and a rose window. The symmetry is obvious and striking with the three major arched entrances reminiscent of Notre Dame in Paris. This dichotomy between the sketch and the competition entry reveals how Richardson expressed his belief in the heavy materiality of the Romanesque as opposed to the lighter, vertical, gothic image expected for the competition. It is interesting how he allowed an early concept to become modified through design development to conform to the competition requirements.

Hunt, Richard Morris (1827–1895)

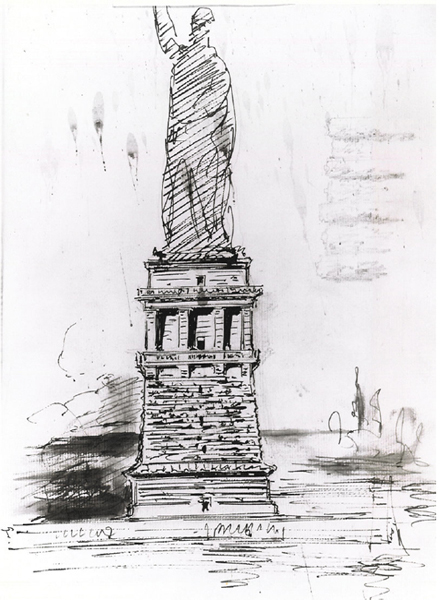

Sketch for the base of the Statue of Liberty, The Museum of the American Architectural Foundation, Box 1865, 11 1/8 × 7 3/8 in., Graphite, ink, and wash on paper

Richard Morris Hunt, the first American architect to have attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, brought back a French classical monumental architecture pervaded by idealism combined with practicality. Hunt's architecture was an eclectic blending of neogothic, neogrec and French neoclassical influence, contrasted by the picturesque wood frame cottages he designed in Newport (Stein, 1986). He was influential in the founding of the American Institute of Architects in 1857 and was its third president (Baker, 1980).

Hunt was born in Vermont in 1827. After his father's death, the family left for an unintentionally extended twelve-year trip to Europe. While living in France, Hunt applied to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and was accepted in 1846. He chose the atelier of Hector Martin Lefuel and during his last years in Paris worked with him on the Pavillon de la Bibliothéque of the Louvre. He traveled widely while living in Europe, a practice he continued throughout his life. Returning to New York City in 1855, he started his practice designing small projects and instructing students in an atelier atmosphere. His first notable project was the Studio Building completed in 1858, a space designed particularly for the needs of artists. He was well established by the 1860s, designing skyscrapers and apartment buildings. Several of his numerous buildings include the Stuyvesant Apartments, the Tribune Building skyscraper in 1876 and monuments such as the Seventh Regimental Monument in Central Park (1873). Later in his life, he was commissioned to design large mansions for wealthy families as the Biltmore in Asheville and summer cottages in Newport, and then the Administration Building for the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893.

Most likely because of his strong relationships in France, Hunt took part in the planning for the Statue of Liberty in the early 1880s. With the sculpture by the artist Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi begun, a Franco-American Union was gathered to manage the project. Hunt was named architect and construction was begun on the pedestal in 1884 (Baker, 1980; Trachtenberg and Hyman, 1986). Hunt's challenge was to connect the star-shaped foundation of Fort Wood with the sculpture. He chose to design a rusticated stone base with a parapet cornice as a firm setting for the statue. Since he was attempting to unify the look of the fortress with the smooth texture of the sculpture, the rusticated base became more refined as it ascended acts as this transition.

This sketch (Figure 4.2) captures one iteration in his design exploration. Detailing the rusticated stone with graphite pencil, the remainder of the sketch consists of ink and wash over graphite. Proportionally the pedestal commands a larger portion of the composition than that of the final solution. It appears elongated and distorted possibly because the pedestal was his concern and he wanted to visualize its articulation. The previously resolved issue of the sculpture, less of his concern, could be vaguely placed with wash. The statue remained part of the composition but the emphasis of this sketch was to design the base. The details of the rustication and the proposed columns over a loggia space have been more carefully articulated, substantially more than the background. The right side of the page shows an enlarged detail of the stone coursing, again reinforcing his interest. In this case, interpreting Hunt's intention may be obvious. The purpose of sketches differs as to the questions being asked. Here Hunt was concentrating on one aspect of the design, not trying to visualize the whole, which may have left the entire composition disproportionate. Interestingly, once built the pedestal became a dominant feature of the composition. Invariably necessary to lift liberty into the air, it still prevailed.

White, Stanford (1853–1906)

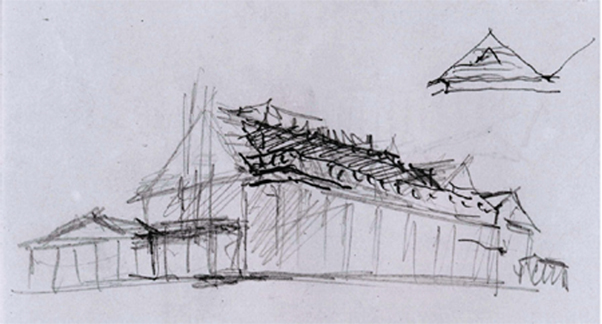

Freehand sketches of large estates, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, White DR 35, SW46:19, 4.74 × 7 in., Graphite on paper

An American architect with an eclectic style, Stanford White was a partner in the successful firm of McKim, Mead and White. White was originally intending to study painting, but was counseled to consider architecture. In 1872, after receiving a degree from New York University, he found work with the architectural practice of H. H. Richardson in Boston. Richardson had attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and his design process reflected that education. As an apprentice, White was exposed to Richardson's Romanesque since Trinity Church was being constructed during his tenure in the firm. It was in Richardson's office that he met his future partner, Charles Follon McKim. In 1878, White traveled to Europe for a period of almost a year. Upon returning from Europe he joined McKim and Mead as a third partner, replacing the retiring William Bigelow. In a scandal that almost overshadowed his prolific architectural career, he was fatally shot at the age of fifty-three.

The following are a few of the projects for which he was the partner responsible; the Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, 1887, the New York Life Insurance Building, Omaha, Nebraska, 1890, Judson Memorial Church, Washington Square, 1888–1893, the Metropolitan Club built between 1892 and 1894, and Tiffany and Company in New York City, 1903–1906. Throughout his career, White designed numerous shingle style homes for the rich and famous. The precedent for his neoclassical architecture employed elements from the past, arbitrarily including Châteauesque, French provincial, Venetian, French and German Renaissance, in unique combinations and variations.

This example of a sketch by Stanford White is remarkably playful (Figure 4.3). Johann Huizinga and Hans-Georg Gadamer outline the philosophical aspects of play as having boundaries to sketch against, being representational, an all absorbing endeavor, conveying a method of learning and displaying a give and take of dialogue. Considering a definition of play, White found intelligibility in this image. He was quickly sketching the building's form conceived in his mind's eye while learning about the building in the process. As it emerged on the paper, he could visualize its potential. Play also involves representation as White was imagining this project, he was seeing the building rather than the paper as a substitute (Wollheim, 1971). He was consciously accepting boundaries, never sketching anything other than the building, providing a ground plane and a sense of perspective. The verticals as possible columns on the porch have been sketched so quickly they have transformed from columns to resemble n's and m's. These lines seem to skip off the page in some instances and in other cases they appear continuous. This implies he could not stop long enough to lift the pencil off the page. As another aspect of play, White was engrossed in the action of the play, the dialogue of the ‘give and take.’ He could draw one line and it responded with another as his mind interacted with the image. The sketch facilitating discourse shows a softer pencil lead over a first general outline. The latter demonstrative roof and balustrade are more forceful in an effort to obliterate the original roof expression. It is possible to surmise the areas of the design that most concerned him at the moment.

In a catalogue of projects by McKim, Mead and White, Leland Roth includes a project coordinated by White, the A. A. Pope Residence in Farmington, Connecticut. The building with its strong eave balustrade and taller central portion seems to strongly resemble this sketch by White. Roth indicates that the project was influenced by the Pope's daughter Theodate who had architectural education and participated with the design. With this in mind, White's sketch may also represent a mode of communication and discussion between two architects.

Sullivan, Louis (1856–1924)

Study of ornamental frame for Richard Morris Hunt memorial portrait for Inland Architect, August 7, 1895, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, FLLW/LHS 123, 17 × 20.3cm, Pencil on paper

Known for his ‘evolutionistic’ botanical style, Louis Sullivan was born in 1856 (Twombly and Menocal, 2000). He entered Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1872. Sullivan was briefly employed by Frank Furness and later moved to Chicago to work with William Le Baron Jenny before enrolling at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1874. Disappointed by his experience in Vaudremer's atelier, Sullivan instead spent his time studying Paris architecture and traveling to Rome and Florence. In 1879 he started with Dankmar Adler as a freelance draughtsman in Chicago. This firm eventually became Adler and Sullivan and was influential in the development of the skyscraper and the building of Chicago. Sullivan's role in the firm involved the ‘composition of façades and the design of ornamentation’ (Twombly and Menocal, 2000, p. 84).

Upon the closing of his firm shortly before his death in 1924, Sullivan moved all of the firm's architectural drawings to storage. Of these drawings, he retained approximately 100 sketches consisting largely of botanical and geometric ornament. These sketches make up the entirety of drawings by Sullivan found in collections today (Twombly and Menocal, 2000). Why Sullivan chose these particular images is a matter of speculation. They may have reflected a more direct expression of his inspiration, creativity, or personal architectural style.

Sullivan's architectural style involved massive volumes contrasted with intricate ornamentation. Narcisco Menocal writes about Sullivan's use of ornament: ‘Louis Sullivan's concept of architectural and ornamental design was based on a belief that the universe was sustained by a cosmic rhythm. Change, flow, and one entity turning into another were effects of a universal becoming. … In that scheme, beauty emerges from a never-ending transformation of all things into new entities’ (Twombly and Menocal, 2000, p. 73). The ornament was, for Sullivan, an enhancing part of otherwise straight-forward steel frame buildings.

This study, from 1895, is an ornamental frame for the Richard Morris Hunt memorial portrait (Figure 4.4). It is typical of Sullivan's studies for ornament, displaying intertwined organic shapes, composed of light guidelines with darker areas for detail. It appears to be a running band of foliage; the top edge and the indicated centerline suggest a linear pattern, one that would be repeated across the frame. This centerline reveals that the sketch is only half of the intended ornament. It was not necessary for Sullivan to complete the entire frieze, as he was able to make a judgment from a small section. This became his point of decision, whether to continue or reject the proposal. By using an underlying geometry, the ornate and complex foliage pattern could appear loose and haphazard, yet it could be precisely duplicated.

When drawing the negative space (the shadows) rather than the positive outline of the foliage, Sullivan was simulating and testing a future three-dimensional effect. The sketch, consistently undeveloped across the page, resembles a doodling that did not need to be completed.

Although this sketch represents only a small detail of ornament, it may be central to understanding Sullivan's architecture. It seems to act as appliqué to the functional spaces, in such a way that the ornament becomes the skin on the steel frame. Sullivan's buildings reflect the ‘organic’ on two different levels – in the way the architecture developed, and the allusions to nature found in the ornament. This, coupled with his desire to retain such sketches as evidence of his design, assists to understand the focus of Sullivan's architecture (Andrews, 1985).

Ferriss, Hugh (1889–1962)

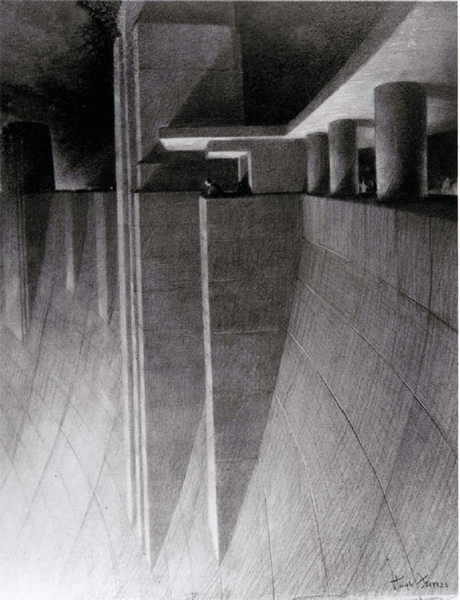

Crest of Boulder, Hoover Dam, The Power in Buildings series, September 14 (between 1943 and 1953), Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, NYDA.1000.001.00010, 30.7 × 23.3cm, Charcoal on tracing paper on board

Although Hugh Ferriss was from a different generation than Louis Sullivan, he represents the attitudes of the architects designing buildings scraping the skies of American cities. Primarily an illustrator, it is important to include him in this section because he did much to promote the future of cities with his drawings and sketches of emotive and dramatically lit urban structures.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, he received a professional education in architecture from Washington University. A school immersed in beaux-arts teaching methods, he graduated in 1911. After completing school he journeyed to New York City to work for Cass Gilbert. A licensed architect, Ferriss found work rendering buildings for architects such as Harvey Wiley Corbett. Paul Goldberger writes that Ferriss became interested in New York City's new zoning ordinance, and in 1916 he drew a series of five drawings describing building mass and the pyramid shapes that the ordinances implied. ‘Ferriss's drawing style became a crucial factor in shaping the priorities of the 1920's: his visions of the impact of the zoning law were to affect the age as much as the law itself, as masonry buildings endeavored to take on the feeling of sculpted mountains, their shape suddenly more important than their historical detail of even their style’ (Goldberger, 1982, p. 58). Preparing his visions for a utopia, he exhibited ‘Drawings of the Future City’ in 1925 and in 1929 he published Metropolis of Tomorrow. Continuing to illustrate for a wide variety of architects he commented that his purpose was to convey a certain aspect of reality in an exciting way when the project was in still primarily in the architect's mind (Leich, 1980). Later in his life he received a grant to travel the United States recording important contemporary architecture, resulting in the book Power in Buildings.

The buildings in Hugh Ferriss' drawings were not of his design but in a sense he created the method by which they would be comprehended. They could be considered sketches by virtue of their conceptual qualities. Ferriss resembles the futurist architect Sant'Elia who seduced an ideal and appealed to an emotional position. In the New York Times, Peter Blake reviewed the show Power in Buildings and wrote: ‘ … Ferriss speaks (and writes) softly, but carries an awfully big pencil’. Blake was implying their dynamic vision but also their powerful meaning (Leich, 1980, p. 31).

This sketch from the Power in Buildings series (Figure 4.5) presents a dramatic view of Hoover Dam. In a reversal, strong light is emitting from below exaggerating the height of the observation platform. The stark slope of the concrete mass fades away into emptiness further evoking this perception. The lone figure helps the viewer comprehend the immense scale. On close inspection the sketch is entirely freehand utilizing the ambiguous texture of a pliable media. Ferriss was known to have implored soft pencil, charcoal and crayon, subsequently removing the medium for highlights with a kneaded eraser or a knife. The use of smudged soft crayon produced an eerie foggy halo. In this case the soft medium presented both less defined edges and high contrast. Not a preparatory sketch like others in this book, the design by Gordon B. Kauffmann has been transformed by the hands of Ferriss. The sketch puts the viewer in awe of the dam's ability to extract power and the sheer magnitude of its size. It suggests the light emitting from below represents the glow of the generating electricity.

Hugh Ferriss lived until modernism had reached a peak, but his methods strongly speak of an architecture of masonry, of mass and solidity. His sketches were less about accuracy and more about seduction in an attempt to influence the perception of architecture.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andrews, D.S. (1985). Louis Sullivan and the Polemics of Modern Architecture. University of Illinois Press.

Baker, P.R. (1980). Richard Morris Hunt. MIT Press.

Baldwin, C.C. (1976). Stanford White. Da Capo Press.

Charernbhak, W. (1981). Chicago School Architects and their Critics. UMI Research Press.

Douglas, G.H. (1996). Skyscrapers: A Social History of the Very Tall Building in America. McFarland and Co.

Elia, Mario Manieri (1996). Louis Henry Sullivan. Princeton Architectural Press.

Fleming, J., Honour, H. and Pevsner, N. (1998). The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Penguin Books.

Gadamer, H-G. (1989). Truth and Method. Crossroad.

Goldberger, P. (1982). The Skyscraper. Alfred A. Knopf.

Hambly, M. (1988). Drawing Instruments, 1580–1980. Sotheby's Publications.

Hitchcock, H-R. and Johnson, P. (1996). The International Style. W.W. Norton.

Huizinga, J. (1970). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Harper and Row.

Huxtable, A.L. (1982). The Tall Building Artistically Reconsidered: The Search for a Skyscraper Style. Pantheon Books.

Landau, S.B. and Condit, C.W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. Yale University Press.

Leich, J.F. (1980). Architectural Visions, the Drawings of Hugh Ferriss. Watson-Guptill.

Menocal, N.G. (1981). Architecture as Nature: The Transcendentalist Idea of Louis Sullivan. University of Wisconsin Press.

Morrison, H. revised by Samuelson, T.J. (1935, 1998). Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture. W.W. Norton and Company.

O'Gorman, J.F. (1987). H.H. Richardson, Architectural Forms for an American Society. The University of Chicago Press.

Ochsner, J.K. (1982). H.H. Richardson, Complete Architectural Works. MIT Press.

Pokinski, D.F. (1984). The Development of the American Modern Style. UMI Research Press.

Roth, L. (1973). A Monograph of the Works by McKim, Mead and White, 1879–1915. Benjamin Blom.

Roth, L.M. (1979). A Concise History of American Architecture. Harper and Row.

Scully, V. (1955). The Shingle Style, Architectural Theory and Design from Richardson to the Origins of Wright. Yale University Press.

Stein, S.R. (1986). The Architecture of Richard Morris Hunt. The University of Chicago Press.

Sullivan, L.H. (1924). The Autobiography of an Idea. Press of the AIA, Inc.

Trachtenberg, M. and Hyman, I. (1986). The Statue of Liberty. Penguin Books.

Twombly, R. (1986). Louis Sullivan: His Life and Work. Viking.

Twombly, R. and Menocal, N.G. (2000). Louis Sullivan: The Poetry of Architecture. W.W. Norton and Company.

Van Vynckt, R. ed. (1993). International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture. St. James Press.

Wodehouse, L. (1988). White of McKim, Mead and White. Garland Publishing.

Wollheim, R, (1971). On Art and its Objects: An Introduction to Aesthetics. Harper and Row.