CHAPTER 6

EARLY MODERN (1910–1930)

This period, approximately 1910 to 1930, was architecturally very fertile in anticipation of the modernist movement. The relatively small and localized movements of expressionism, futurism/Nuove Tendenze, the Amsterdam School and De Stijl, the Bauhaus, and constructivism each contributed to the roots of modernism in Europe. Although many of the included architects lived and practiced well into the twentieth century, their architectural legacies have been identified with this era and these movements. Their sketches are indicative of these associations, and more specifically the sketches’ techniques were infused with ideology in anticipation of modernism. They advocated destruction of the ruling class and the tight control of the academy, as was evidenced by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The world was enjoying the benefits of the Industrial Revolution and found hope in the power of the machine. Early modern architects encouraged a departure from the past and traditional architecture, encouraging a near total abandonment of ornament. All were utopian and idealistic, promoting architecture as a vehicle to advance a new social agenda. Some may even be viewed as revolutionary, placing their faith in the worker and supporting the craftsman, and the replacement of established conventions. Whether because of ideology or political/economic circumstances, as a whole they built little. Each of these groups depended on visual communication to disseminate their movement's ideology. They used media to assist in the conception of new approaches to architectural design. These drawings and sketches could represent an idealistic future in the case of Antonio Sant'Elia’s Città Nuova, whose sleek, dynamic images of industrial architecture spoke of a mechanized future. Sketches by Erich Mendelsohn embrace the fast lines and movement of the machine age by describing a plasticity of materials. Gustave Eiffel explored innovative uses for steel and glass, designing bridges and temporary structures. Michel de Klerk and Gerrit Rietveld, the most successful in seeing architecture through to construction, exercised extreme control over their images. Their sketches revealed the considered use of media to explore form and articulate details. El Lissitzky and Vladimir Tatlin moved easily between art and architecture, thereby enhancing their sketching skills. Julia Morgan, with her extensive practice, found the need to conceptualize through quick sketches and rely on her employees to translate her ideas into construction drawings. In contrast, Hermann Finsterlin chose sketches as a means to explore and disseminate theories of expressionism, using sketches as polemical dialogue. To elaborate on the uses of sketches by these architects it is important to place them in the context of their belief systems.

Expressionism in architecture grew out of the art movement of the same name in Germany. The major players included the architects Hans Poelzig, Peter Behrens, Max and Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius, and Hermann Finsterlin. Active in the years following World War I, they embraced utopian ideals with mysticism. They proposed architecture as ‘a total work of art;’ manipulating forms sculpturally and drawing upon human senses (Pehnt, 1973, p. 19). This reliance on emotions found metaphors in cave and mountain designs. Many of their beliefs were represented by a crystal; it was transparent and evoked concepts of stars and light. Accordingly, these architects began a series of communications and created a theoretical dialogue called the Gläserne Kette, or glass chain (Pehnt, 1973). They felt that expressionism was a new method of communication rather than a distinct style (Borsi and Konig, 1967). The economic depression following the war led to a period of limited construction. This situation, paired with a belief in the spiritual nature of the creative act, produced a large amount of theoretical images which might be referred to as paper architecture (Pehnt, 1985). This architecture, primarily ‘built’ on paper, was less concerned with function than with architectural form (Pehnt, 1985). These drawings and sketches often exhibited fluid expressions of amoebic shapes, as in the case of Finsterlin's abstract masses, and colorful emotional allusions by architects such as Poelzig and Bruno Taut.

Nuove Tendenze (heavily influenced by Austrian Secession) and futurism were primarily Italian movements that looked to industry and technology with an anti-historicist view. Visions of the machine age, with its electricity and new building materials, spurred an exploration of the city as a monumental and efficient social mechanism. The architectural sketches by Sant'Elia described a streamlined future of often molded forms, focusing less on specific materials and more on seamless elasticity. He was, in fact, visualizing prestressed concrete, and saw it as the material of the future (da Costa Meyer, 1995; Conrads, 1970). His architecture, with its flowing lines, expressed the speed of the machine metaphorically, but he also concentrated on architecture for machines, such as railway stations, power plants, and dams. These sketches used exaggerated and undefined scale to reinforce the monumentality of the speculative architecture. His stepped-back structures anticipate modernist skyscrapers and engage the observer's imagination (da Costa Meyer, 1995). Repetitive lines suggest buildings in motion and further the ideology of futurist architecture.

Two movements that evolved in a somewhat parallel fashion, and in close proximity to each other, were De Stijl and the Amsterdam School. Philosophically quite different, the architects of the Amsterdam School rejected classicism, concentrating instead on relationships between ‘functionalism and beauty’ (Bock, Johannisse and Stissi, 1997, p. 9). Beginning in the early 1900s, this movement stemmed from the common belief system of architects such as H. P. Berlage, J. M. van der May, M. de Klerk, and Piet Kramer. Fueled by political policy governing city expansion and mandates for workers’ housing, these architects searched for sculptural forms that could be economically efficient and, thus, respond to social needs (Bock, Johannisse and Stissi, 1997; Casciato, 1996). Concerned with materials and construction methods, the architects of the Amsterdam School used sketches and drawings to envision building systems and massing. Not stylistically cohesive, the drawings and sketches by these architects were substantially diverse.

Many drawings (plans and elevations) of apartment buildings designed by de Klerk remain in archives. His sketches are characterized by combinations of selected ornament contrasted by building austerity. Drawn with a controlled hand, his sketches explore material intersections and the articulation of openings. His plans follow a trend in architectural drawing conventions by using symbols with legends and diagram techniques. The thickness of the walls was particularly important, considering he built almost exclusively with masonry. The De Stijl architects also built with masonry and explored massive geometric forms made from concrete. In contrast to the Amsterdam School, however, they eliminated decoration and most color, and assembled rectangular forms (de Wit, 1983). Naturally, their drawings and sketches had a minimal, abstract expression.

In nearby Germany, Gropius was transforming the former art school Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar. (It is important to note that Gropius has been included in the modern chapter because of his significant influence on the style.) Based on the theory of the ‘artist as exalted craftsman,’ the Bauhaus attempted to unify the building and a whole, integrating its various elements (Conrads, 1970, p. 49). Gropius advocated bringing together sculpture, painting, and crafts into the design of the built environment. The masters of the Bauhaus were concerned with teaching craftsmanship in a workshop setting; besides craft, science, and theory, the school also provided instruction in drawing, painting, life drawing, composition, technical and perspective drawing, and ornament and industrial design (Conrads, 1970). These studios taught the techniques of sketching from memory and imagination (Conrads, 1970). Possibly stemming from a need to consider objects for domestic use, they also employed axonometric drawings. These two-dimensional projections showed three sides of the object or building equally, and were comprised of parallel lines which could be constructed with straight edges. They suggested the preciseness of the machine and reveled in the abstraction (Naylor, 1968).

First organized in Moscow in 1921, constructivism reconsidered the concept of creative activity. Its artists and architects promoted a post-revolutionary society of the working class, using modern construction materials instead of traditional modes of craft (Perloff and Reed, 2003). With this idea came the design not of aesthetic objects but of mass production. Advocating a functional and objective approach, they embraced the future of technology. With artists and architects such as Theo van Doesburg, Kasimir Malevich, Lissitzky, and Tatlin, constructivists sought expanded plasticity and spatial dynamics (Perloff and Reed, 2003). Disseminating their ideas through political posters and ideological exhibitions, they found a unique style of spatial composition. Very linear and extending into all directions, the two-dimensional images advocated their three-dimensional concerns. Many of the sketches employed hard lines and solid planes of color using precision to emphasize ideas of solid and void. Both Lissitzky and Tatlin translated these conceptual explorations into physical constructions utilizing them as they would a sketch, making and remaking in quick succession.

SKETCHES

Architects of this period were building, but such tumultuous times saw an increase in the development of theory and the retention of sketches. Most of these architects obtained at least some training from art and architectural education institutions; most of them continued to associate with schools of architecture for a large part of their lives. Such relationships with education may have encouraged the archiving of their images, since students and colleagues recognized them as contributions to the history of architecture. Part of the reason sketches remain from this period stems from the sketches as inherently imbued with ideological assertions. As with Boullée and Piranesi, the availability of publication increased the collection and distribution of these artifacts. The remarkably attractive, fluid sketches by Mendelsohn and the painterly illustration sketches by Bruno Taut, for example, may have assured their preservation. Their dramatic perspective angles and fantastic architectural form contributed to capturing public imagination. In some cases, the sketches (especially by the expressionists and constructivists) were used in publication or were hung in exhibitions. The availability of tools may have contributed to the extensive existing design studies. The age of machines meant the manufacture of drawing surfaces, and plentiful inexpensive instruments. Most likely the single feature that allowed the retention of architectural sketches from these movements pertains to the recognition and respect given to these sketches as remnants of creativity. A Renaissance of expression emerged from the rejection of tradition and the established academy, and encouraged a generation of prolific architects who produced a spectrum of exciting sketches.

Sant'Elia, Antonio (1888–1916)

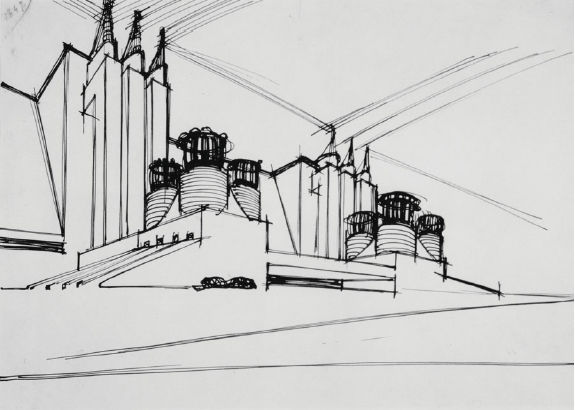

Study for a power station, 1913, Musei Civici di Como, 21 28cm, Ink on paper

Antonio Sant'Elia was born in Como, Italy, 1888. He studied at the G. Castellini Arts and Crafts Institute, specializing in public works construction. After receiving his Master Builder Diploma in 1906, he joined the technical staff that was completing the Villoresi Canal. In 1913 Sant'Elia opened his own architectural practice in Milan, and he collaborated with the painter Dudreville on the national competition for the new headquarters of the Cassa di Risparmio, Piazza delle Erbe, in Verona. Sant'Elia joined the Volunteer Cyclists in World War I and died during the eighth battle of Isonzo in October 1916.

Although Sant'Elia’s early influence was Art Nouveau, he was certainly aware of Frank Lloyd Wright, and much of his early work indicates that he looked to Otto Wagner and the Secessionists for inspiration (Caramel and Longatti, 1987). Sant'Elia was grounded in his knowledge of industrialization and changes in the contemporary city (Caramel and Longatti, 1987). He produced a series of drawings of his vision of the future city (the Città Nuova) and, with the Nuove Tendenze group, he exhibited these drawings along with his first version of the Manifesto of Futurist Architecture. As a result of this exhibition, he met members of the futurist movement, who embraced his vision; and his work thereafter became associated with this movement.

Sant'Elia’s concern for a new city that embraced technology is evident in both the subjects and techniques of his sketches. Many of them are not connected to commissioned projects, but are explorations of the monumental qualities of the power of technology, with subjects such as railway and power stations. This sketch (Figure 6.1), dated 1913, shows just such a monumentally scaled building, given the title of power station. What makes this building seem so powerful is its lack of context. Its stark, dramatic view speaks of the building's function, not the human experience.

The straight, possibly ruled lines were reinforced through repetition, with lines drawn on top of each other. The overall effect accents the nervous vibrations of electricity which flows through the building. Another technique which adds to its monumental quality is the sharp angles of the perspective view. In most of Sant'Elia’s sketches, he uses perspective instead of plans or elevations; he needed to envision the building as a whole impression and was not concerned with the nature of the interior spaces. He was representing the compelling expression of movement and ‘swiftness’ of the structure – terms he referred to in his Manifesto. He uses two-point perspective, with the points very close to each other, to increase the height of the building. He also employed a low horizon line to contribute to this impression.

The items that represent the power of electricity – the turbines – are prominently placed to the front of this station. They allow the building to speak about its function, proving that the architecture of the future has a role in creating a new society. The sketch lacks building details such as windows, doors, or material qualities, giving it a streamlined, machine-like feel. This ‘machine aesthetic’ was also mentioned in the tenets of the Manifesto: ‘[w]e have got to invent and remake the futurist city similar to an immense, tumultuous, agile, mobile building site, dynamic in every part, and the futurist building similar to a gigantic machine’ (Caramel and Longatti, 1987, p. 302).

Sant'Elia likely had full knowledge that many of his designs would not be built. This is reflected in his connection with the expressionist movement of the period and the ‘paper’ architecture resulting from both the ideology of impending modernism or the general economic depression of the times that prevented much building.

de Klerk, Michel (1884–1923)

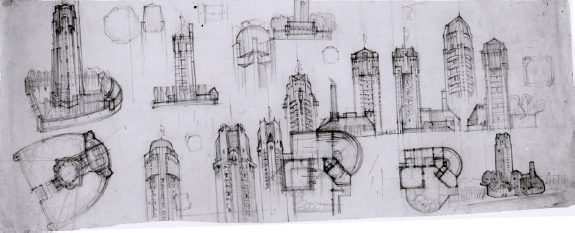

Sketch of design for a water tower with service buildings in reinforced concrete, 1912, NAI, archive de Klerk 26.3/0321, 31.9 · 79.1cm, Pencil on tracing paper

The recognized leader of the Amsterdam School, Michel de Klerk wrote little about his theories; he demonstrated his non-rationalist approach to architecture through his buildings. Born in an Amsterdam suburb in 1884, he demonstrated drawing skills from childhood. When he was fourteen, the architect Eduard Cuypers (Cuijpers) saw his drawings when visiting his school. Immediately, de Klerk began work in Cuypers’ office, first as a clerk, then as a draughtsman, and finally as supervisor of works-in-progress (Frank, 1984). Employed there for twelve years, his first building opportunity came when he was hired by the architect H. A. J. Baanders to design the apartment house Johannes Vermeerplein (Frank, 1984). Soon after this project's completion, the client, Klaas Hille, asked de Klerk to design the first block on the Spaarndammerplantsoen, and it was during this time that he opened his own office.

The worker's housing, Spaarndammerbuurt, was tremendously influenced by the building codes for housing in Amsterdam at the time. Wolfgang Pehnt describes de Klerk's solution for the apartment building as basically the design of façades (1973). Over the next few years, de Klerk was involved with the design of the remaining two blocks, each with a slightly different approach. With windows flush to the façade, he employed various brick patterns; vertical to meet the street (and to demarcate the stories on the third block), horizontal string courses, some set in wave patterns, and others pulled away from the façade to articulate entrances.

Michel de Klerk's architecture was primarily constructed of brick using traditional construction methods. His mature work did not find any reference in history, although his influences included English Arts and Crafts, Scandinavian vernacular, and local Dutch models (de Wit, 1983). In addition to his concern for composition, Wim de Wit writes that: ‘[de Klerk's] work shows a search for an organically suggestive expression of life’ (de Wit, 1983, p. 41). This expression was constructed with mass rather than planes and evoked a picturesque aesthetic (Frank, 1984).

Early in his career, de Klerk entered several competitions in order to expose his practice, taking second place in three contests. This sketch (Figure 6.2) shows design explorations for his entry in the 1912 Architectura et Amicita competition for a water tower with service buildings. His solution to the program was a tower made of exposed concrete (Bock, Johannisse and Stissi, 1997). The page has been covered with various elevations and perspectives, describing primarily the articulation of the shaft and top of the tower. The composition and ‘look’ of a cylindrical reservoir encased in a square structure was being explored. The numerous sketches study the relative expression of the structure in comparison to the container; in some cases the structure has been emphasized, while others accentuate the reservoir. Dotted site plans display alternative layouts for the juxtaposition of the tower and the service buildings.

de Klerk sketched with strong vertical lines, emphasizing the vertical feeling of the tower. Rendered primarily freehand with a few ruled guidelines, he used heavy lines to outline the forms, strengthening this verticality. The proposals appear surprisingly finished, which indicates that he was working out the design to some degree of completion in order to evaluate the alternate solutions. It was unnecessary to draw the whole tower, since a portion and the ‘cap’ conveyed most of the information. de Klerk was analyzing only the connection between the shaft and the top, purposefully ignoring the connection between the column and the ground. This sketch was mainly searching for a compositional appearance of the tower.

Eiffel, Gustave (1832–1923)

Eiffel Tower, detail of the opening of the arch, Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource; Musée d'Orsay, ARO 1981–1297 [53] (ART 177561), 27.5 × 42.5cm, Graphite, pen and ink

Gustave Eiffel was born in 1832 in Dijon, France, where his parents owned a warehouse for the Epinac mines. With an interest in mechanical instruments and industry, Eiffel studied chemistry at the State School of Civil Engineering. In 1850, he found work as an apprentice in metallurgy in the Châtillon-sur-Seine foundry, learning the technical and financial dimensions of the industry. His experience with construction began when he started working with Charles Nepveu, the railway engineer. When Nepveu's business dwindled, Eiffel joined the Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Ouest as a bridge designer (Loyrette, 1985).

Through a series of events, Eiffel later returned to Nepveu to work on a bridge for the Saint-Germain Railroad and, soon after, the Bordeaux Bridge (1858–1860) (Loyrette, 1985). He opened his own consulting firm in 1865, the Eiffel Company, with Maurice Koechlin as a collaborator, and designed portable bridges, some being sent as far as Manila and Saigon. Other large projects completed by the firm were the rail station at Pest in Hungary (1875) and the bridge over the Douro/Garabit viaduct that same year (Loyrette, 1985).

Eiffel is of course best known for the iconic tower of the 1889 Exhibition in Paris. In 1886, a call was made for an exhibition building possibly including a tower. Although an open competition, it was really directed to the Eiffel Company, who had been circulating a design for a tower since 1884 (Harriss, 1975). The idea for the design originated with Koechlin, but it was a Company collaboration. The exhibition tower stood approximately 300 meters tall and was constructed of wrought iron, chosen for its strength balanced by its weight (Harriss, 1975).

This sketch (Figure 6.3) has been attributed to Gustave Eiffel. There is convincing evidence that this sketch is from his hand: the page was included with papers acquired by the Musée d'Orsay from the Eiffel family. Eiffel was the managing partner in the firm and would have wanted to control such a high-profile project. He was also the engineer responsible for decisions in the firm, and his reputation for structural stability was essential. Considering what is known of Eiffel's sketching skills, comparison of this sketch to the initial drawing by Koechlin reveals disparate styles.

The page has six variations for the structure describing the base of the tower, all done with graphite and ink. Each one explores the bracing of the splayed base using single, double, cross-bracing, or circular reinforcing. The platform on the first level has been studied for thickness and function. One sketch shows a perfect circle inscribed between the legs, considering the efficient weight distribution and a concern for a geometric aesthetic. Eiffel was also contemplating the dimensions of the attachment to the ground with proportional measurement. One variation displays two sets of numbers divided by a centerline, which consider the width of the legs in comparison to the negative space.

These sketches describe the refinement of the bracing in regard to the aesthetic appearance of the base. Koechlin's early design drawing is of a tower that was far too light and flimsy to withstand the forces of the wind, a drawing that may have revealed his inexperience. Conversely, throughout his career Eiffel studied the wind's effect on his structures, even utilizing wind tunnels. His knowledge and experience show in his concern for the base; Eiffel was attempting to reconcile structural integrity with proportions and geometry. This sketch revealing a confident hand, suggests a vehicle to project thoughts pertaining to both the construction and appearance of the tower.

Lissitzky, Lazar Markovich (1890–1941)

Proun, study, c. 1920–1923, VanAbbemuseum, Inv.nr.244, 40.3 × 39cm, Charcoal on paper

El Lissitzky, educated as an architect and engineer, is best known for his explorations of spatial construction and constructivist graphics. Born in the province of Smolensk, Russia, in 1890, he left for Germany in 1909 to study at the Technische Hochschüle in Darmstadt. With the advent of World War I, he returned to study engineering and architecture at the Riga Polytechnic Institute in Moscow. He was recruited by Marc Chagall to teach architecture and graphic arts at the Vitebsk Popular Art Institute, and began his association with Theo Van Doesburg, Kazimir Malevich, Hans Arp, Mart Stam, among others, and the contructivist and suprematist movements (Lissitzky, 1976; Perloff and Reed, 2003).

With little opportunity for work in architecture, Lissitzky found an artistic outlet in graphic design: books, Soviet propaganda posters, and photomontage. In 1919 he began a series of two- and three-dimensional projects he called Prouns. Lissitzky was experimenting with the 'problems of the perception of plastic elements in space' and the 'optimum harmony of very simple geometric forms in their dynamic and static relationships' (Lissitzky, 1976, p. 49). These geometric, spatial abstractions were titled for an acronym 'Project for the affirmation of the new' in art (Mansbach, 1987, p. 109; Perloff and Reed, 2003, p. 7).

Lissitsky had been searching for a venue beyond painting, one which extended to the creation of space (Mansbach, 1987). The Prouns questioned the tradition of perspective that used a single point by employing multiple visual points (Lissitzky, 1976). The resulting effect produced geometric compositions that seemed to float in space, with lines and planes extending in all directions. The Prouns took many forms, from prints and paintings to room-scale installations.

Both spatial and compositional, Lissitzky viewed the Proun constructions as sketches, since they referred to a beginning. They were explorations reaching toward perfection; continuously in process, they could never reach a state of completion (Mansbach, 1987). The opposite page (Figure 6.4) exhibits a graphite study for a Proun. The freehand techniques and scratchy pencil lines indicate its preliminary qualities. The sketch studies overlapping planes of various values on the left, balanced by open space on the right. Many lines appear to visually extend beyond the page connecting the Proun with the space beyond it. The composition emphasizes the correlation between the object and the ground surrounding it. More volumetrically complete, this sketch may have been the three-dimensional equivalent of the large-scale exploration. The image may represent a spatial construction that was abstracted for transfer to a lithograph.

Although Lissitzky maintained positive attitudes toward the machine aesthetic, it is not surprising that this Proun has been explored freehand. The manual, of the hand, was continually a concern for him, especially in relationship to vision. For him, the hand took a primary role in any creative activity (Perloff and Reed, 2003). Thus, the constructed installation Prouns consisted of the materials of the machine age, tempered by his concern for craftsmanship and tactility. This suggests that the starting point for all of his designs emerged from hand sketches.

Lissitzky used his Prouns to speculate on the construction of elements in space. Theoretical by nature, they inherently referred to an ideology rather than their objective qualities. Paradoxically, the action of hanging these images in galleries added to the perception of them as finished objects. If all of the Prouns completed by Lissitzky were intended to be preliminary, then this sketch may actually be a preliminary for a preliminary.

Tatlin, Vladimir Evgrafovich (1885–1953)

Sketch of the Monument to the Third International, c. 1919, Moderna Museet

Vladimir Tatlin was born in Moscow in 1885. He attended the Kharkov Technical High School and left soon after for the seaport of Odessa in 1902. There he found work on a ship that sailed the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. He studied at the I.D. Seliverstova School of Arts at Penza and the Moscow College of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. It was through the painter Mikhail Larionov that he was introduced to artists and writers in Moscow and St. Petersburg (Milner, 1983; Zhadova, 1988). Around 1913, Tatlin began a career as a painter and became a member of the Union of Youth. His early work resembles impressionism and the paintings of the Kandinsky circle. In 1914, he visited Paris and was inspired by the work of the fauvists and French cubist painting. Although influenced by these groups, his work contained a vitality found in Russian art (Milner, 1983). During this period, he began the constructions he called 'painterly reliefs,' paintings with three-dimensional appliqué (Milner, 1983, pp. 92, 132).

An active artist throughout his life, Tatlin's repertoire was varied: drawing, painting, three-dimensional constructions, theater set design, clothing and costume design, furniture and domestic objects, architecture, and even a flying machine. Tatlin was continually interested in materiality, and especially exploring 'materials as language' (Milner, 1983, p. 94).

Talin's most influential and celebrated project was his proposal model for the Monument to the Third International, commissioned by the Department of Artistic Work of the People's Commissariat for Enlightenment in 1920. The project, although never realized as a building, was an icon for theoreticians that combined the social aspects of communism with constructivist art (Milner, 1983). The model displayed a series of leaning conical spirals meant to rotate at the various levels; the top portion was to contain a telegraph office speculatively intending to transmit images. Employing ruled lines and carefully constructed dimensions, this image (Figure 6.5) shows a diagrammatic elevation of the planned project. The page can be considered a sketch because it describes a preliminary or preparatory diagram, although it appears similar to an etching. This view of the monument reveals little context, consisting only of a few industrial buildings, either very distant or diminished in scale by the tower. Consistent with a diagram, Tatlin labeled the various levels of the tower in case the audience was not able to perceive his intent. The monument's structure and proportions are completely proposed, but as a building that was to house government offices, the sketch provided little explanation of mass or inhabitable volume.

Although the page's overall impression is not sketchy in technique, it reflects both the miniature model and the model as idea. The much-publicized design became an icon for the Soviet Revolution. It symbolized the forward-looking communist state, embracing a new ideology, and had far-reaching impact as a rallying point for an optimistic future. John Milner speculates that its form represents the 'progress of communism' and the leaning spirals mimic a step forward (1983, p. 156). They are also suggestive of Hermes or Mercury, and the stepped transition resembles a Ziggurat (Milner, 1983).

As a sketch, this image could be left unfinished and unresolved, since its purpose was ideological. The proposed monument speculated on a future and may have contributed to moving a political machine. It did not need to be fully resolved as architecture, instead it could suggest a belief system and through its vagueness, it could conjure and implore a whole country. Tatlin continued to alter and redesign the tower over the years. This continual manipulation resembles qualities of sketches as in process and the ambiguity of this image to be transformed. The Monument of the Third International acted as a social mechanism, the sketch and especially the model through their visual powers were able to help promote an ideological goal.

Mendelsohn, Erich (1887–1953)

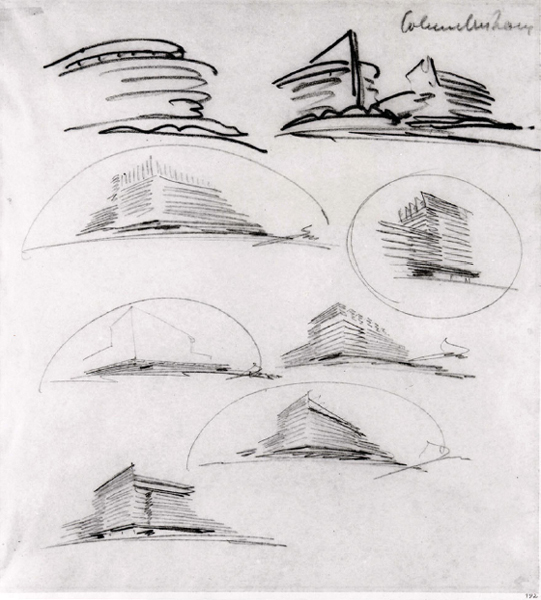

Columbushaus exploratory sketches, 1931–1932, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Hdz EM 192, 31.5 × 25.4cm, Ink on paper

Erich Mendelsohn was born in 1887 in Allenstein, East Prussia, now Poland. He studied architecture at the Technische Hochschule of Berlin, and upon finishing his education he was introduced to expressionism and became associated with the Blaue Reiter group. After the Einstein Research Laboratory, his first commission, Mendelsohn obtained such urban architectural projects as the Schocken Department stores in Nuremberg and Chemnitz, and Columbushaus in Berlin. In 1933, he emigrated to England, keeping studios in both London and Jerusalem. He moved to the United States in 1941, taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and completed various projects, including synagogues, community centers and a hospital, until his death in 1953.

Throughout his career, Mendelsohn talked about his work in terms of 'dynamic functionalism,' which referred to feeling, imagination, and '... expression in movement of the forces inherent in building materials' (Pehnt, 1973, p. 125). He used these fluid qualities of the expressionist movement in his design for the Einstein Research Laboratory. It was intended to be built in the plastic material of concrete, but was eventually made of brick with a sculptural layer of concrete on top. Mendelsohn's architecture has been tied to expressionism and futurism and is often considered a precursor to modernism. His buildings, such as the Schocken Department stores, convey his concern for the strong horizontals of motion and the layering of transparency and solidity. His use of concrete, steel, and glass speaks of the human-made world of the machine. Mendelsohn had great interest in sketching throughout his lifetime; he would send sketches home from his post at the Russian front, writing that they were representative of a type of architecture he wanted to create. Some of these wartime sketches resemble flowing sand dunes and may have inspired his early architecture.

This is a page (Figure 6.6) of possibilities for the façade and volumetric massing of the Columbushaus project. All of the sketches contain strong horizontal lines, precursors for the repetitive ribbon windows. The lines, each representing one floor of the building, reveal Mendelsohn's concern for scale in these early attempts. The façade, with its curvature or straightness yet to be determined, considers its relationship to the urban edge of the street: some sketches include first floor shops. Although located on a busy street in Berlin, the building is sketched so as to ignore the context. The sketches that are circled or have an arced horizon may be acting as background or simply denoting the more promising proposals. The articulation and emphasis on the corner is seen in the finished building which is curved at one end. The final work of construction for the Columbushaus was to lift the top story, like a cap. In these sketches, the many alternatives for this accented upper floor can be seen.

Mendelsohn's technique is characterized by quickly drawn, confident, bold lines, which are straight and double back on themselves in their swiftness. He used ink to create these dark and definitive lines; this fluid media best represented his ideas for a fluid architecture. He wanted to analyze the entire building quickly and did not rework or erase a specific image, but continued to redraw the images until they matched the concept in his mind's eye. Two variations on a curved iteration and six variations on the straight proposal might explain a discrepancy in the techniques of the sketch.

The fact that Mendelsohn was not taking time to erase or cross out his sketches may indicate how he was thinking. Once an image reached a certain level of completion, he evaluated it and then moved on to the next. The wholeness of each sketch was necessary for its evaluation and critique.

Morgan, Julia (1872–1957)

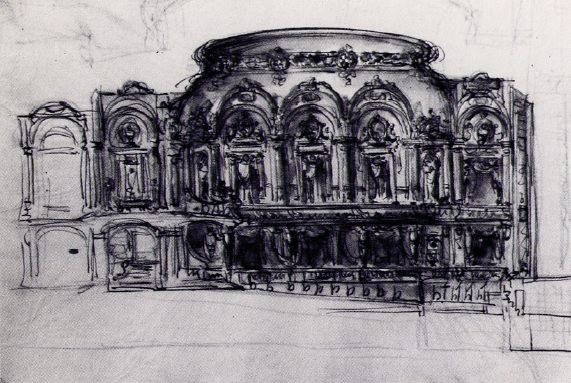

Student rendering of a theater in a palace, Ecole des Beaux-Arts, 1902, Environmental Design Archives, 8.75 × 13 in., Graphite, ink, watercolor and gouache on yellow tracing paper, mounted on cream drawing paper

An architect practicing in the early twentieth century, Julia Morgan completed nearly seven hundred buildings. Her work did not reflect a particular style, but responded to site conditions and client needs. Designing with function as her priority, she also had a concern for details, light, color, and texture (Boutelle, 1988). Many of her buildings displayed Renaissance, classical, vernacular, Arts and Crafts, Spanish, and Native American references.

Born in San Francisco, Morgan began her architectural education at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1890. While studying for an engineering degree, she met the architect/professor Bernard Maybeck. He encouraged her interest in architecture, and she worked in his office for a year following her graduation. She moved to Paris in 1896 and soon after she was admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, becoming the first woman matriculated into the architecture program. She returned to the United States in 1902 to begin her own practice.

As diverse as her architectural language, her repertoire of projects varied from domestic to institutional to commercial. Her first projects included university commissions such as a bell tower and gymnasium for Mills College in Oakland, followed by a Sorority House and the Baptist Divinity School for Berkeley. From churches such as the First Swedish Baptist Church and Saint John's Presbyterian Church, to markets (Sacramento Public Market) and hospitals (Kings Daughters Home), she controlled the design of every project. Well known for her numerous buildings for the YWCA, the most prominent are in Oakland (1913–1915), Honolulu (1926–1927) and San Francisco (1929–1930).

In her association with the Hearst family she produced two celebrated houses. Morgan first finished the Hacienda del Pozo de Verona for Phoebe Hearst before designing a mansion complex on the southern coast of California for media tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Named San Simeon, the cottages were completed in a style described by Hearst as 'Renaissance style from southern Spain' (Boutelle, 1988, p. 177). The main building, fashioned after a church, was designed to display Hearst's collection of paintings and art objects.

Most of Morgan's architectural drawings were destroyed when she closed her office in 1950, although some of her sketches from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts still exist (Boutelle, 1988). This sketch (Figure 6.7) dated December 3, 1901 was a preliminary design for her final Ecole competition. The program called for a theater in a palace. Receiving a 'first mention' for the project, the sketch demonstrates tremendous skill in beaux-arts composition and decoration. It represents an artistic control over ink and wash to achieve a complete impression. Details and ornament seem to have been thoroughly explored even though the swags and balustrades have been rendered as a series of squiggly 'w's.' It displays qualities that may be considered simultaneously precise and imprecise. Not necessarily a paradox, the sketch represents the beaux-arts technique of explaining the totality while providing minimal articulation of detail. From a distance, the sketch appears complete with shadow and reflection. All parts have been included – even the draping of the doorway curtains. On closer inspection, the doubled lines show the apparent search for the appropriate curve. These lines stop short of intersection exhibiting the sketch's preparatory quality. The pilasters have been indicated by simple horizontal and vertical marks and appear to list to the left showing her hurried lines. Being both precise and imprecise, this sketch seeks interpretation.

Rietveld, Gerrit Thomas (1888–1964)

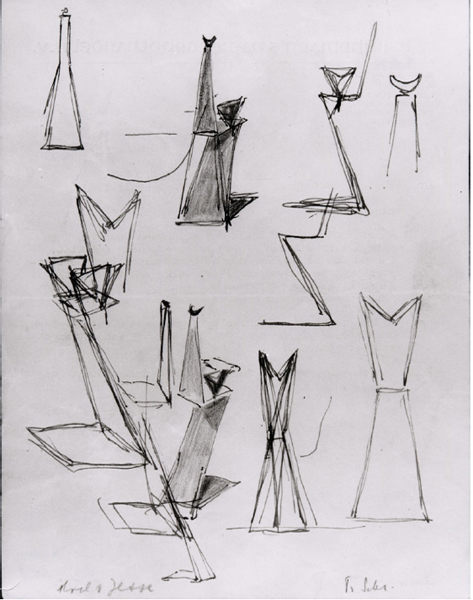

Rough draft variation of zigzag child's chair Jesse, July 13, 1950, RSA, 485 A 012, 20.5 × 15.7cm, Crayon, ink on paper

Originally a furniture builder, Gerrit Rietveld was partially responsible for the architectural ideals of the De Stijl movement of the early 1920s. His Schröder House epitomized many of the movement's beliefs, including simplicity of form, verticals and horizontals that intersect and penetrate each other, primary colors, asymmetrical balance, and elements separated by space (Brown, 1958).

Born in Utrecht, Netherlands, Rietveld joined his father's furniture workshop at a young age. He attended evening classes in architecture, studying with the architect P. J. C. Klaarhamer. By 1917, he opened his own furniture workshop, and a year later he met various members of the newly formed group calling themselves De Stijl (Brown, 1958). Beginning his architectural practice in Utrecht he felt an affinity for the modern movement.

For several years, Rietveld exhibited his furniture across Europe, and even sent a chair to a Bauhaus show in Weimar in 1923 (Brown, 1958). Of all his well-known furniture designs, the Red Blue chair was the most exhibited and publicized. The chair was constructed of plywood planes, painted red and blue, floating through black vertical and horizontal sticks that overlapped each other. The compositionally elegant chair resembles a three-dimensional version of a Mondrian painting, although it was built prior to Mondrian's mature work.

Rietveld routinely destroyed many of his architectural drawings to make room for his latest projects; but with his prolific practice, evidence of his architectural drawing skills remains (Baroni, 1977; Vöge and Overy, 1993). These drawings demonstrate various stages in Rietveld's design process: construction diagrams, alterations and refinement, and ambiguous first proposals.

The sketch page (Figure 6.8) shows variations for a child's highchair studied from numerous angles. The sketches have been strewn across the page, with several of them overlapping and filling the available open space. The objects were sketched in ink then treated with colored pencil to provide texture and shading to several (possibly the most promising) renditions. Rietveld was using ink to outline the forms and emphasize the overall composition. The heavy, reinforced profiles suggest the construction of the chairs and the emphasis that Rietveld often put on the edges of his furniture. This technique darkened the profile and allowed for better viewing of the shape, and also accented the frequently used materials of plywood or planks of wood. The planar qualities of the chairs suggest the extension of these planes into space, reflecting some elements of De Stijl philosophy. For example, the ends of the black sticks supporting the planes of the Red Blue chair were painted a contrasting yellow. The repeated parallel lines were also necessary to imitate the thickness of the wood. Structurally, providing an approximation of the dimensions of the wood helped him to visualize the stability of the chair. Similar to the Zigzag chair, he was evaluating the balance and counterbalance that would provide steadiness.

This highchair appears to be based on the design of the Zigzag chair, designed approximately ten years earlier. Because the seat needed to be higher than the Zigzag chair Rietveld was evaluating alternatives for proportion – variations for the length of the base plane in relation to the taller 'leg.' In another attempt to visualize the completed chair, Rietveld used colored pencils to represent the shadows and tones of an anticipated red finish. These sketches allowed him to inspect the design three-dimensionally, prior to building a model or prototype.

Finsterlin, Hermann (1887—1973)

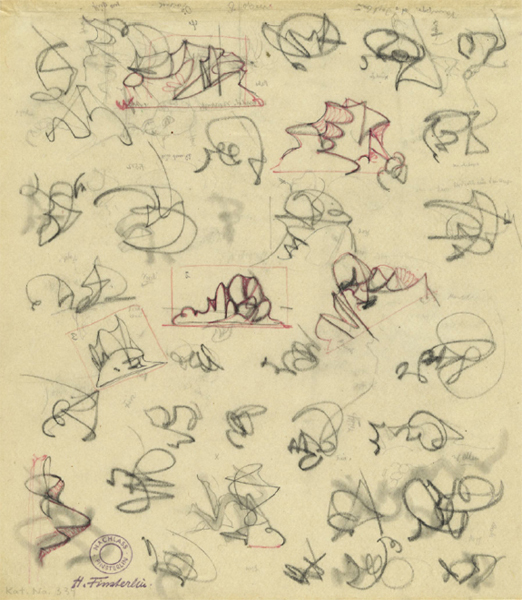

Sketchbook page, c. 1920, Hamburger Kunsthalle/bpk, KH 11a, 31.9 25.8cm, Pencil and color pencil on transparent paper

An artist and fantasy architect of German expressionism, Hermann Finsterlin was born in Munich. After first studying the natural sciences and philosophy at Munich University, he redirected his studies to painting (Pehnt, 1973). In 1919, the architects of the Arbeitsrat group sponsored a competition inviting artists to show 'ideal projects' (Pehnt, 1973, p. 91). Entering the 'Exhibition for Unknown Architects,' Finsterlin thus began his association with these expressionist architects. (Pehnt, 1973).

This group of like-minded artists and architects, feeling somewhat isolated in their views, formed a community of correspondents called Die Gläserne Kette (The Glass Chain) which included Finsterlin, Bruno and Max Taut, Walter Gropius, Hans Hansen, and Hans Scharoun. In the early 1920s, Finsterlin attempted to build, but those projects were never realized and he dedicated himself to painting after 1924. This 'paper architecture' did not require a client or even a structure; rather, it encouraged fantasy and imagination and provided efficient dissemination of his beliefs. Always a theorist and idealist, Finsterlin was interested in theosophy and continued to study the 'biological creative urge in art which made use of the human medium' (Pehnt, 1973, p. 96).

Hermann Finsterlin speculated on the architecture of the future. Like Mendelsohn, his life-long friend, he was attracted to the abstraction of natural forms. His buildings often appear misshapen, conceived in a flowing elastic material that questions the tenets of architecture. Wolfgang Pehnt describes his paintings as 'exciting form-landscape in which interior and exterior are drawn together into continuous planes and spatial entities' (Pehnt, 1973, p. 97).

This page by Finsterlin (Figure 6.9) reveals a creative process searching for form. It appears that he sketched continuously, making a series of looped, abstract figures. Because of his use of translucent paper, many of the images have been framed and numbered from both sides. The squiggles are reminiscent of 'automatic writing' – seemingly made quickly, showing smooth lines in a frenzy of activity. With this deliberate technique, he chose to make curls rather than straight lines, providing him with results that anticipated the architecture he was envisioning. It appears he was attempting to instigate as much as possible accidentally into the process.

Consistent with expressionist ideology, sketches were generally valued for revealing creative inspiration (Pehnt, 1985). Edward Casey describes this as 'pure possibility,' a term used to explain a function of the imagination (Casey, 1976). Pure possibility suggests that all things are possible and at this early stage, for Finsterlin, no image was ruled out. Finsterlin put down what forms appeared in his head without judgment, and thus everything contained potential. Using the cognitive and visual techniques of resemblance and association, these images were so ambiguous that he could read anything into their vague form.

Once these sketches appeared on the paper, Finsterlin could, in a system of evaluation, highlight the forms he felt held the most promise. He framed several of these chosen sketches and, in pencil, began architectural articulation on others. The philosopher Richard Wollheim concerning translating abstract forms writes, 'Now my suggestion is that in so far as we see a drawing as a representation, instead of as a configuration of lines and strokes, the incongruity between what we draw and what we see disappears' (Wollheim, 1973, p. 22). These uncontrolled scribbles provided Finsterlin with images of 'pure possibility,' but the process required an evaluation phase to enable him to envision the sketches as future architecture.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andersson, H.O. and Bedoire, F. (1986). Swedish Architecture Drawings 1940–1970. Byggförlaget.

Baroni, D. (1977). The Furniture of Gerrit Thomas Rietveld. Barron's.

Benevolo, L. (1977). History of Modern Architecture. MIT Press.

Bock, M.S., Johannisse, S. and Stissi, V. (1997). Michel de Klerk, Architect and Artist of the Amsterdam School, 1884–1923. NAI Publishers.

Borsi, F. and Konig, G.K. (1967). Architettura Dell'Espressionismo. Vitali e Ghianda.

Boutelle, S.H. (1988). Julia Morgan, Architect. Abbeville Press.

Brown, T.M. (1958). The Work of G. Rietveld, Architect. MIT Press.

Caramel, L. and Longatti, A. (1987). Antonio Sant'Elia: The Complete Works. Arnoldo Mondadori.

Casciato, M. (1996). The Amsterdam School. 010 Publishers.

Casey, E.S. (1976). Imagining: A Phenomenological Study. Indiana University Press.

Conrads, U. ed. (1970). Programs and Manifestoes in 20th-Century Architecture. MIT Press.

Constant, C. (1994). The Woodland Cemetery: Toward a Spiritual Landscape, Erik Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz 1915—61. Byggförlager.

Cruickshank, D. ed. (1988). Erik Gunnar Asplund. The Architect's Journal.

da Costa Meyer, E. (1995). The Work of Antonio Sant'Elia: Retreat into the Future. Yale University Press.

de Wit, W. (1983). The Amsterdam School: Dutch Expressionist Architecture, 1915–1930. The Smithsonian Institution/MIT Press.

Drijver, P. (2001). How to Construct Rietveld Furniture. Bussum.

Droste, M. (1990). Bauhaus 1919–1933. Benedikt Taschen.

Frank, S.S. (1984). Michel de Klerk, 1884–1923: An Architect of the Amsterdam School. UMI Research Press.

Harriss, J. (1975). The Tallest Tower: Eiffel and the Belle Epoque. Houghton Mifflin.

Hochman, E.S. (1997). Bauhaus: Crucible of Modernism. Fromm International.

Holmdahl, G., Lind, S.I. and Ödeen, K. eds (1950). Gunnar Asplund Architect 1885–1940: Plans Sketches and Photographs. AB Tidskriften Byggmästaren.

James, C. (1990). Julia Morgan. Chelsea House.

James, K. (1997). Erich Mendelsohn and the Architecture of German Modernism. Cambridge University Press.

Küper, M. and von Zijl, I. (1992). Gerrit Th. Rietveld: The Complete Works. Centraal Museum.

Levin, M.R. (1989). When the Eiffel Tower Was New: French Visions of Progress at the Centennial of the Revolution. The Trustees of Mount Holyoke College.

Lissitzky, L.M. (1976). El Lissitzky. Galerie Gmurzynska.

Loyrette, H. (1985). Gustave Eiffel. Rizzoli.

Mansbach, S.A. (1978). Visions of Totality: Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Theo Van Doesburg, and El Lissitzky. UMI Research Press.

Margolin, V. (1997). The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917–1946. The University of Chicago Press.

Milner, J. (1983). Vladimir Tatlin and the Russian Avant-Garde. Yale University Press.

Naylor, G. (1968). The Bauhaus. Studio Vista.

Overy, P., Büller, L., Den Oudsten, F. and Mulder, B. (1988). The Rietveld Schröder House. MIT Press.

Pehnt, W. (1973). Expressionist Architecture. Praeger.

Pehnt, W. (1985). Expressionist Architecture in Drawing. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Perloff, N. and Reed, B. eds (2003). Situating El Lissitzky: Vitebsk, Berlin, Moscow. Getty Research Institute.

Sharp, D. (1966). Modern Architecture and Expressionism. Braziller.

Smith, A.C. (2004). Architectural Model as Machine. The Architectural Press.

Vöge, P. and Overy, P. (1993). The Complete Rietveld Furniture. 010 Publishers.

Whitford, F. (1984). Bauhaus. Thames and Hudson.

Wingler, H.M. (1969). The Bauhaus, Weimar Dessau Berlin Chicago. MIT Press.

Wollheim, R. (1973). On Art and the Mind. Penguin Books.

Wrede, S. (1980). The Architecture of Erik Gunnar Asplund. MIT Press.

Zevi, B. (1985). Erich Mendelsohn. Rizzoli.

Zhadova, L.A. ed. (1988). Tatlin. Rizzoli.