March 2

Nam Nyang, Camp 1

Gibbons call far downstream at the edge of hearing, their songs drifting ghostly in the half-light. Delicious minutes pass as the singing continues, then dawn brightens, and their cries fade like dreams. Close to camp, barbets and a grey peacock pheasant start up. Full day begins.

We have at last reached saola habitat, or what we hope is saola habitat. The plan is for separate teams to survey two upstream tributaries that feed the Nam Nyang. We’ll look for tracks in the streamside sands and also for plants that have been nipped in the saola’s telltale manner.

But trouble in camp thwarts an early start.

Mok Keo reports to Simeuang that our stores of rice are badly depleted. Evidently some of the guides, led by Viengxai, cook an additional meal after the rest of us have gone to bed. They’ve done this every night. On hearing the news, Robichaud does his best to swallow his anger; still, his eyes look pained and his jaw muscles are tight. “It is so often like this. They say they want to go into the forest, and you tell them how many days it will be, but as soon as they can, they start eating up the supplies so they can go home sooner.” It seems we are now short by several days’ rations.

The camp manager, in this case Simeuang, and the senior guide, Mok Keo, are supposed to monitor both supplies and the guides’ behavior, but laxity has been the rule. Once, years ago, a camp manager on a survey with Timmins and Robichaud actually engineered the sabotage of provisions. It turned out that he was much besotted with a young woman back at home. He could not bear to be away from her, or perhaps he could not bear the thought of other men around her. Whenever Timmins and Robichaud left camp to look for wildlife, he and the unoccupied guides feasted like rats in a granary. Olay’s father, Bounthavy, then worked for WCS as a driver. Bounthavy was a fixer; he got things done. He saw through all pretense, and no one could deceive him. Robichaud promoted him to camp boss, and from that day forward there was no more provision-raiding or malingering in the field. Lamentably, Bounthavy has not come with us to the Nam Nyang.

Robichaud calls the guides together to say that supplies are not to be touched except at established mealtimes. Viengxai stands off at a distance, idly hacking a tree with his machete. I watch him with resentment. He stands near enough to hear but far enough away to demonstrate contempt for the group. Essentially he has turned his back on any question of responsibility or blame. The meeting ends with a general feeling of discomfort.

Robichaud assigns Touy to stay in camp and guard against mischief. He also instructs Simeuang henceforward to sleep with the rice sacks in his tent if necessary.

Even with Touy remaining in camp, we are anxious about our gear. The previous day, in an exchange of banter, Viengxai asked Robichaud for more cigarettes. Robichaud answered, “I don’t smoke.”

“But I know you have them. I saw them in your pack.”

It was true. Robichaud kept a small stash for use as gifts, deep in his pack, buried among twenty kilos of miscellany. Viengxai must have searched the pack. Robichaud was flabbergasted. “I have never had one of these guys go through my stuff before.” The realization brought considerable dismay. Over many years, he said, the scores of Lao guides he had traveled with had been good companions, many superb. But now a bad apple seemed to be corrupting the spirit of our team.

Meanwhile, I knew Viengxai had picked through my stuff because, apart from the mishap of the water bottle, I’d repeatedly found the placement of ditty bags and other gear rearranged and reordered. Nothing had been taken from either of us, but perhaps the time for taking had not arrived. We worried that while we hunted saola in the forest, Viengxai might hunt for other things among our goods. So we stowed everything in our tents and “locked” them. Using scraps of orange twine that Robichaud claimed was the only orange twine in camp, we tied our tent zippers closed in such a way that they could not be opened without the twine being cut. To the zippers of the two tents Robichaud affixed notes that said in Lao DO NOT ENTER.

On mine I added, in English, MAY A TICK CRAWL UP YOUR PENIS.

Simeuang, Sone, and Olay head out to investigate a side stream roughly opposite camp. Robichaud, Meet, and I will ascend the river past the farthest limit of our night survey and search for sign of saola along a second tributary draining from the back of Phou Vang.

The riverbed, in the present dry season, is a population of limestone boulders laced with pools and twisting channels. The dry rocks range from gray to white and are black when wet, fluted and sleekly carved, like melons scooped with a spoon. The riverbed rises in stages, a pattern known as pool and drop. We clamber up a rockfall, then stroll a bedrock plain. Another rockfall, another plain. The water level has been falling, and where the flats have recently dried, the egg cases of regiments of insects, now hatched and flown, remain cemented to the rock. The bedrock in many places is potholed with concavities of perfect roundness, like boreholes for wells. These must be the locations of recurrent eddies, where flood-stage whirlpools, with an abrasive slurry of gravel at their bottoms, drill down into the rock. Some of the holes are dry, but many hold water and are connected to each other by lateral fissures and subsurface channels. I look in one and see a fish swim by. Farther along, we come to a slab of Swiss-cheese rock that floodwaters have broken loose and tilted vertically, so that its pothole is a porthole, a chest-high window on the river.

We stop to consult the map. Swiftlets swarm overhead, as thick as mosquitoes above a pond. In the forest on river left an Indian cuckoo chants, “One more bottle. One more bottle.” From river right we hear the shouts of a red-vented barbet: “Wow! Wow!” The canyon is loud and bright, but Robichaud is concerned that he’s seen no otter scat on the rocks near the big pools, where the water is deep. We see plenty of fish in the shadowy depths. The habitat should be ideal for the acrobatic weasels, but none seems present. There is only one conclusion: “The Vietnamese have trapped them out.”

The side stream we seek is only a kilometer ahead. As we climb, the shelves of potholed rock become less ordered, more broken. Tossed by floods, their seeming portholes give them the look of scuttled ships. On them grows a thin layer of moss, which is invisible when dry, but with the least moisture, even the dampness of a sandal sole, it becomes as slippery as grease. We jump from one canted slab to another, judging carefully the distance, the slope, and the probable purchase of the landing. Sometimes we carom from the face of a rock too steep to land on in order to reach a boulder where we can. Where the riverbed resembles the contorted pavement of an earthquaked highway, we teeter like tightrope walkers along uptilted spines of rock. We climb laddered cascades where every toehold and handhold threatens to give way. At one treacherous passage, Robichaud calls out, “Black ice here!” although of course it is not black ice but rather the tropical equivalent in frictionless algae. Anyone who tried to cross it and failed would slide down a slant of rock into a crevice whose bottom we cannot see. We skirt the edge of the algae patch, feet slipping uncontrollably, by pulling ourselves along on roots and limbs that hang from the riverbank.

Robichaud has reached the mouth of the side stream. He whistles for Meet and me to come on. Almost immediately we encounter the remains of yet another Vietnamese camp. Then, a little farther, a glint of metal catches our eye. Implausibly, three scraps of aluminum lie half buried in flood wrack from the tributary. We dig them out. They are twisted and mud-stained. It seems likely they once rimmed some kind of circular opening. Rivet holes are spaced along the outside edges. A rounded fold completes the inner edge.

Nakai–Nam Theun held no strategic importance during America’s Vietnam War, but Mu Gia Pass, where the Ho Chi Minh Trail veered from North Vietnam into Laos, lies immediately south of the protected area, not far as a jet flies. Virtually every square foot of Mu Gia was bombed to a fare-thee-well. No other place saw worse. If you look at the map for unexploded ordnance in Vietnam and Laos, Mu Gia is a solid mass of red. It had so much UXO that after the war, bomb-removal teams declined to bid on clearing it. It was simply too dangerous. The engineers who finally restored transportation through that part of the mountains ultimately cut a new pass, which was cheaper and safer than restoring the old one.

Although NNT wasn’t a target and didn’t lie on a regular flight path, pilots might have flown over it if they were lost, disabled, or scouting. Even B-52s, having dropped their loads on Hanoi or Haiphong, might have headed home this way to bases in Thailand. There was also the CIA’s disgraceful Secret War, centered farther north, in Laos, for which air support came from units that officially did not exist and that operated from places that could not be found on anyone’s map. In our weeks in NNT, we have seen not a single aircraft overhead, nor have we heard any. But in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the skies above the Nam Nyang were unlikely to have been so empty.

Possibly the scraps of aluminum we found had washed down from the wreckage of a plane on a shoulder of Phou Vang, or they came from an ejected external fuel tank or other discarded equipment.

In more populous areas, such artifacts would have been scavenged. Odd scraps of metal might be refashioned as digging or cutting tools, kitchenware, or patches over holes in a floor, or they might be traded to a scrapper for a few kip. Robichaud recalls that on a survey near Mu Gia he occasionally heard something like distant thunder, although the day was clear and the sound seemed to come from the plain below, not the sky. His guide explained that teams of villagers were at work hunting for unexploded bombs. When they found one, they dug a hole beneath it, made a fire in the hole, stoked it, and retired to a place of safety. If the fire was hot enough and burned long enough, the bomb exploded. Then the villagers gathered the shrapnel, which they sold to itinerant metal buyers. Of course, exploding bombs was risky—sometimes the digging jostled a trigger or the fire required more fuel at the wrong moment. There were accidents.

There were even more accidents with the tennis-ball-size cluster bombs that the Lao, borrowing a word from English, call bombies. A few hundred bombies filled a pod, and a pod looked like an ordinary bomb. A plane might carry an array of pods. When dropped, the pods split open in midair, scattering bombies over a large area, the idea being to constrain the movement of enemy troops and supplies. Some were designed to lie dormant until stepped on. Others were supposed to explode on contact with the ground but had a dismal detonation rate, leaving many more dormant. The United States dropped a colossal number of bombies on Laos, approximately 270 million—roughly one for every American back in the States and a hundred for every Lao then living. Nearly a third of them failed to go off. After the war ended, eighty million bombies lay unexploded in Lao soils. Over the ensuing decades many of them greeted the ill-placed foot, the probing of a farmer’s shovel, or the curiosity of a child with flesh-shredding vehemence. They made the landscape evil. Civilian postwar casualties in Laos run well into the tens of thousands, and each of those victims has been wholly innocent, many of them children. The gift of bombies, and all the agony, amputation, and fatality that comes with them, is one that few Americans know they have made, but more than forty years later it is a gift that keeps on giving.

We leave behind the metal scraps and start up the creek, where the footing soon deteriorates. It is always my left foot that goes truant, sliding out from me on moss, dead leaves, wet stone, or, as it does now, on stone that wears the invisible coat of algae that imparts slickness to everything at this altitude. The streambed is no more than twenty yards wide, and the humidity of the forest lubricates what stream flow does not.

Robichaud scans the streamsides for certain plants and for shoals where sand or mud might accumulate and reveal tracks. Unfortunately we encounter none of the first and little of the second. One small spit of mud betrays signs of a hog badger rooting for worms, but in general the creek is too steep and flood-washed to hold the material that would record a track. The stream banks, too, tell us nothing, for they are a solid mass of roots. We are disappointed, but the morning is pleasant and no leeches have appeared. The chirping of frogs brackets us fore and aft as we make our way upstream.

I count three Vietnamese camps in the last kilometer. The creek has steepened, and now the height of the waterfalls is greater than the length of the shelves between them. Climbing their wet scarps is like scaling a slick-bark tree in the rain. On one, I carefully copy Robichaud’s handholds and footholds: a grip on a knob of rock here, toes in a damp hollow there, then stretch up to grab the edge of a bowl of gravel, but the edge of the bowl breaks off, and I slide harmlessly down a dozen messy feet. I elect to take a more laborious route up the wall of vine and scrub that encloses the creek and join the others on the ledge above. Previously I’d told Robichaud that if it looked like I might slow him down, I would stop and wait while he and Meet continued upward. Now, I say, this looks like the place to do so. I’ll let the saola come to me.

All right, he replies, but first we’ll eat our lunch together.

Our plastic bags contain sticky rice in roasted cakes, and for each of us a grilled fish not much larger than a man’s thumb, mostly head and skeleton. While we pick bones from our teeth, Robichaud says he had a powerful dream the night before. He dreamt that at a banding site he caught a bald eagle, a magnificent, proud, fierce bird, the first he’d ever captured, amid circumstances that were bizarre and full of portent. The dream left him feeling optimistic. He adds that the Lao believe that dreams about dangerous animals, especially snakes, bring good luck. “Maybe I should have dreamt about a cobra.”

Meet lets me look at his rifle. It is Soviet-made, with Cyrillic letters marking the on-off setting for automatic fire. He says it is the third AK-47 he’s been issued in a little more than a decade. Continuing the show-and-tell, Robichaud pulls his field book from a cargo pocket. He keeps several ten-thousand-kip notes and a picture of Martha in it. He shows the picture to Meet and asks if he’s ever seen a saola. No, Meet answers. He’s only heard about them. What about dhole? Robichaud asks.

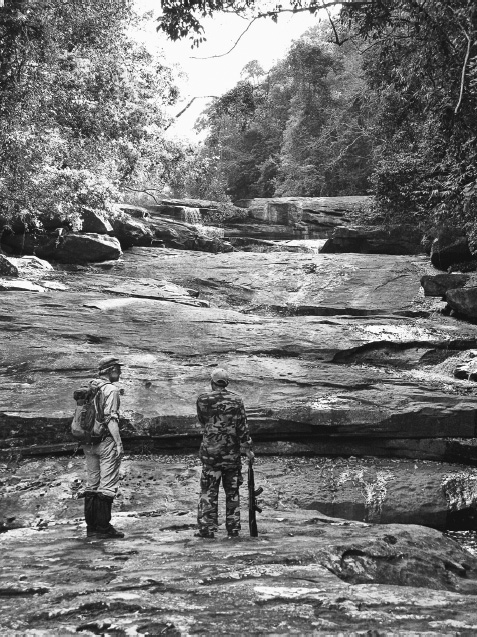

Meet (right) and author climbing a Nam Nyang tributary. (Courtesy William Robichaud)

Meet says the area used to have dhole, but they are gone now—they all died, perhaps of some disease. Packs of dhole used to take a few buffalo—no one had cattle in those days, and tigers used to kill an occasional pig or other livestock. That was twenty years ago, when he was a boy. He is thirty-three now.

Then Meet makes the spectacular statement that dhole would urinate on a trail, and fumes from their urine would blind sambar and muntjac, making them easy to kill. He says that when he was ten, he used to see places around the village where dholes had rested and slept. About that time, somebody in the village shot a large cat; he can’t remember if it was a tiger or a leopard. Everybody came to see the carcass. That was roughly the same time that a large cat, maybe the same one, came into a house in Ban Nameuy and bit someone on the arm, perhaps trying to drag him off. Now the big cats are pretty much gone, he admits, and in his opinion it is just as well.

Not much later, Robichaud and Meet leave to continue their journey up the creek, and I begin to jot down what Robichaud has lately told me of saola habitat and behavior. But my eyes are heavy. I am too drowsy, or too lazy, to write.

A shaft of sunlight falls on a patch of dry, flat rock. My pack makes a pillow. I stretch out, giving in to gravity, my weight on warm stone. In no time, I am asleep.

Points of interest:

• One way to think of saola is to imagine an ancestral not-quite cow, not-quite antelope back amid the eons of the Miocene, between five and twenty-three million years ago. The Earth is changing. Forests that are far more extensive than those of the present have begun to yield to grasslands and savannas. Ancestors of today’s bovids venture into the new habitats, taking advantage of a grass diet, adapting as the millennia pass by, and branching into new species that will lead to the many forms present today. The ancient protosaola, however, remain loyal to their forest home and feed not on grass but on the leaves of trees and herbs, which delight their descendants still.

• Saola are found in broadleaf evergreen forests in the Annamite Mountains that have little or no dry season. Some authorities speculate that the persistence of so ancient a species in so small a geographical range indicates that the Annamites have been ecologically and climatically stable over a remarkable span of time, even as—during the Pleistocene epoch, for instance—other regions experienced major habitat shifts. If this is true, then today’s saola may be an indicator of forests that are among the oldest on the planet, their origins going back tens of thousands of years.1

• At least in some areas, saola are believed to move with the seasons. In the early 1990s Vu Quang hunters said saola moved downslope from the higher mountains during the winter dry season, when the rains decrease and small streams dry up. The rains in Vu Quang can last as long as eight months and produce more than three meters of precipitation—a drenching of more than half an inch a day. Hunters placed their snares to intercept saola and other animals as they moved from high elevations to low ones and back.

• The hooves of saola, fresh from the wild, alive or dead, show heavy wear at the tips, an indication of rocky habitat. The streambeds along which they find their preferred foods tend to be corridors of boulders, and the mountain slopes where the torrents originate are typically walled with scarps.

• In an act of considerable kindness, George Schaller gave me a track cast made from a dead saola in Laos in the mid-1990s. It consists of a square of black fiberglass into which, when fresh, the hooves of the saola had been pressed. Like all ungulates, saola have cloven hooves. The two toes are strongly curved on their outside edges, making an almost oval print, unlike the triangular patterns of most deer. The front feet of Schaller’s sample are roughly two inches long, the rear feet an eighth inch to a quarter inch longer. The track cast hangs on the wall above my desk. Schaller also gave me a second, even more memorable, cast. This one, made of white plaster, shows the light impression of a single hoof. Schaller says that Billy Karesh, the WCS veterinarian, cast it from Martha in Lak Xao while she was alive.

• Once or twice, villagers have reported seeing as many as a half dozen saola at a time. On two or three occasions, they’ve seen four. Are these exaggerations? Sightings of solitary saola, or of a mother and her calf, are generally the rule, although even these are rare—the kind of thing a village hunter remembers as an epochal event, not to be forgotten.

• It is surprising, twenty years after saola first attracted the world’s attention, that so little about the species is known. How big is an individual saola’s range, how much land does it need? Are the ranges of male and female the same or different? How do they court? When do they breed? No one has answers to these questions and many others. In the aftermath of saola’s discovery, hunter interviews seemed to indicate that the females drop their calves in February and March. But Martha, had she survived, would probably have birthed her baby in May, and the two orphaned saola juveniles briefly maintained in FIPI’s botanical garden outside Hanoi in 1994 appear to have been born several months apart.

• Predators of mature saola probably include tiger, leopard, dhole, and humans. Additional predators of young saola may include clouded leopard, sun bear, Asian black bear, and python.

• The diet of the saola is poorly understood, as is the botany of its habitat. Scientific surveys of the saola’s remote forests have focused on cataloging animal species. Knowledge of the regional flora in places like the watershed of the Nam Nyang is generally too fragmentary to carry identifications past the level of genus. If species were to be determined, a large number of plants would undoubtedly be new to science. Like the saola, many of them would be endemic to the Annamite Mountains, found nowhere else.

• If saola are similar to other forest browsers, they require nutrition from several dozen types of plants. A staple of saola diet appears to be one or more species of Schismatoglottis, a genus of the Araceae family.2 Village hunters report that no other animals consume Schismatoglottis in much quantity. Thus if a patch of the plant bears evidence of browsing, and especially if the leaves appear carefully nipped, saola are almost surely present.

• Like other ruminants, the saola has a four-chambered stomach and chews a cud.

• A bovid horn consists of bone encased in a sheath of keratin. In the case of the saola, the bone within the horn grows nearly to the tip, making the horn strong and indicating that it is a serious weapon, good for defense. Saola horns are typically smooth with wear, and hunters report that saola rub their horns against small trees or thrash dense stands of brush. This behavior may have a social or sexual function. In addition, it hones within the animal a keen spatial awareness and a kinesthetic sense of how to wield its horns with accuracy—to block the attacks of enemies or to gore them.

• The challenges of saola conservation verge on epistemology: How do you save a ghost when you are not sure it exists?

Mr. Ka of Ban Kounè has said, “No one sees saola anymore; they’re gone.”

Robichaud replied that, although no one was seeing them ten years ago, they weren’t gone. One day a neighbor of Kong Chan suddenly encountered one, proving they were present all along. How can anyone be sure they are gone now?

In a moment of candor on another occasion, Ka, contradicting himself, told Robichaud that he caught sight of a live saola on the Nam Nyang in 2005. The next year, he saw saola tracks between Ban Kounè and Phou Vang. Ka knows as well as anyone that a few of the animals might remain deep in the forest, in places like the upper Nam Nyang.

In NNT, as elsewhere in the world, not everybody tells the truth all the time, and, at any given time, not all the truth gets told.

Small bees wake me. A dozen or more hover close above my face, some nearly in my nostrils, checking out my chemistry. I blow at them, and they retreat a few inches.

Suddenly, branches dance overhead. A face, rimmed in yellow, gazes down at me. I start to reach for my binoculars, and the face vanishes. For a split second, I glimpse a brown body and long, hairy tail as the branches dance again. An indistinct memory tells me the monkey I saw was the second of two. And now the branches are still.

I replay the image in my groggy mind: the haloed face; the flash of body and tail. I want the monkey to be a douc, a rare, colorful creature native to these mountains. To see a douc, especially alone like this, would be quite a gift. But the snatch of color I saw had no gray or red. This monkey was plainer than a douc. All right, I think, not a douc, but still a gift. It was probably a macaque.

A short while later, I hear Robichaud and Meet on the ledge above. They have found nothing. No more metal from war machines, no sand or mud with interesting tracks, no Schismatoglottis, no stems that show saola nibbles. We return toward camp, descending the shaded, stair-step tributary, and when we reach the channel where the Nam Nyang holds back the forest on either side, the bright sunlight drives off the forest dankness and lightens our steps.

Heading downriver, we again admire the potholes and kettles that are like chains of aquaria. We note a fresh hatch of river flies with sky-blue wings and, a little farther, a cohort of purplish butterflies carpeting the limestone. The insects rise at our approach in a dust devil of indigo. The river water is cool and inviting. At one of the largest and deepest pools we pause. Robichaud releases Meet to return to camp. Then Robichaud and I rinse our filthy shirts and trousers and spread them to dry on the warm boulders. Stripped, we swim. The water is windowpane clear. Bracing. A modest waterfall feeds the pool, and the falling water feels like a massage. I dive and swim for the bottom. The pool glimmers gray and green, with gravel in the depths. Every pebble is sharp and distinct, but the bottom is astonishingly deep and out of reach.

Back in camp, Sone reports that he might have found something. The stream he explored with Simeuang and Olay was steep like ours, heavily scoured, and offered no soft margins that would keep a track. The only game they saw was a black giant squirrel, but Sone also spotted a plant that he says saola eat. Its leaves had been carefully nipped off, one by one. Robichaud says the plant is new to him—it’s not among the saola foods known to biologists—“but everything about saola is new to almost everybody.” He presses the plant into his field book.

We have come a long way to learn two negatives. First, notwithstanding the plant that Sone collected, the upper Nam Nyang seems to lack the vegetation saola prefer. It may be too high or too dry—so much so that, as Robichaud puts it, “the formula is off.” He says the drainages we’ve searched haven’t “felt right.” Robichaud’s mind is not closed on the matter—he thinks further exploration of the upper reaches of the side creeks might show something, but for the present he’s inclined to redirect our search to tributaries lower on the river.

The second negative is that we aren’t effectively in Lao PDR anymore. The people who make use of this watershed—and there have been plenty of them—come from across the Annamite crest. Questions of sovereignty aside, we seem to be in a resource colony of Vietnam, where hunters and rosewood smugglers do as they please.

We gather over the maps. Robichaud lays out several alternative destinations, and the guides speak in Lao and then Sek, their excitement rising, as they debate possible routes. Robichaud and Simeuang briefly speculate about setting a new camp high up between Phou Vang and Phou Hone Kay (Chicken Comb Mountain), above a succession of waterfalls. No one in our group has been there before. It is new territory (except for Vietnamese hunters of eaglewood), and there is a chance, on the high cliffs, that we might see exotic creatures like black leaf monkeys, whose speciation is poorly understood and whose local population is essentially unknown. But the idea passes quickly. Robichaud wants to continue the hunt for saola on the lower Nam Nyang. He’d intended tomorrow to be a rest day, but clouds are gathering, and if it rains, the river rocks will be dangerously slick. The prudent decision is to descend the channel while we can. Robichaud suggests that he and I start down at first light while the guides are still cooking. “Once they get going,” he says, “they’ll be down those rocks like spiders. If we want to see anything, we have to get ahead of them.”

Bone, the least shy of the youngsters from Ban Beuk, is irrepressibly cheerful. He has a scar on one cheek, and most days, in addition to his smile, wears a bright orange T-Mobile World Cup T-shirt. This is his first long trip into the forest, and he shows an interest in everything. After we’ve eaten (sticky rice, a salty broth, and too few fish to satisfy our large group), he accompanies Robichaud and me to the mouth of the tributary that Simeuang and Sone inspected. In the dusk light, we quickly bait a camera trap with fish heads. The white river rocks seem to glow as we cross back to our camp in the dark.

We turn in at 8:00 p.m., and in the dark hours I dream of my children, who are suddenly young again, much younger than Bone. Responding to an urgent call, I have arrived at a house of endless corridors to collect them, but the sirenlike mothers of their playmates delay me. The women are beautiful and seductive. They sing to me in soft Southern voices. I am delightedly melting into their arms when I remember my children. I break from the sirens and fly away—yes, fly—arms out, legs straight back, like Superman, through strange, long rooms. The flying feels like swimming, although at dangerous speeds. I careen around corners, banking into turns. I look in every room for my children. And look, and look. The lovely women are gone and their enchanted singing gone with them, and I am just flying and searching.