March 4

A Tributary of the Nam Nyang

In camp last night, our bellies full and the day’s ordeal behind us, Robichaud told the boys and me a story he’d heard elsewhere in Nakai–Nam Theun:

A team of a dozen Vietnamese discovered a mother lode of eaglewood within the protected area. It constituted a fortune in incense, and the prospect of riches made the poachers crazy. The team fractured, six on a side, each group plotting to do away with the other and keep the treasure for themselves. One day, half the team goes hunting; the other half stays in camp. The camp tenders prepare a large meal and lace it heavily with poison mushrooms. They wait for the others to return, the pot simmering. In due time the others appear, but they come into camp with guns out, blazing. They kill all six of the camp tenders before any can fight back. Then the victorious six help themselves to the steaming meal, which is still on the fire. Of course, it proves to be their last. No one survives. Days later, a small party of Lao happen upon the scene and reconstruct this account from the evidence of the corpses. The punch line in Robichaud’s telling is the title he gives his story. He calls it Nam Theun 2 Reservoir Dogs.

Robichaud laces his speech with movie lore. He has a prodigious gift for recalling plots and whole pages of dialog. On one long walk between villages, I happened to mention that I had never seen Oliver Stone’s Platoon. Over the next several kilometers, Robichaud narrated the action of the film, scene by scene, speaking the lines of leading characters. With a little editing, his performance could have been a one-man one-act play. I do not doubt he could do the same for any number of other films set in Southeast Asia. He told me that in our battle yesterday with the bamboo and on our final steep descent to the river, he couldn’t stop repeating in his mind a line from Predator, a B-grade sweaty-biceps commando vehicle for Arnold Schwarzenegger: “I’ve seen some bad-ass bush before, man, but nothin’ like this.… Makes Cambodia look like Kansas.”

Even apart from the scraps of films in our heads and the scraps of airplanes, bombs, and fuel tanks on the ground, the war is like an echo that follows us around. One day the trail was wide for a stretch, and Robichaud and I walked together. He said, “Here we are, a couple of Americans prowling around in deep forest close to the border of Vietnam. We are traveling with a bunch of Lao guys who wear camo and carry assault rifles, and we are looking for Vietnamese who are doing things we don’t like. The Vietnamese, meanwhile, know that people like us are looking for them, and they don’t want to be found. Sound like anything you’ve heard of before?”

Robichaud was too young to be drafted for the Vietnam War, but I wasn’t. The war and the military draft that fed it were the overriding realities of my teens and early twenties. My father had served as a midrank officer in both World War II and the Korean War, although he never saw action in either conflict. He hadn’t tried to avoid combat; he just wound up in places where it didn’t happen. I think this left him with a sense of unease, a feeling of uncompleted destiny. When Vietnam came along, he expected me to answer the nation’s call, as he had done dutifully in his own time. He did not dwell on the merits of the war, and he didn’t know that while in high school, as soon as I got a driver’s license and had access to a car, I started attending meetings of the antiwar American Friends Service Committee. Later, as I finished college and neared the end of my student draft deferment, he was appalled to learn that I was filing with my draft board as a conscientious objector. It was only a gesture on my part. I knew I would not be granted CO status because my grounds for it were insufficiently religious. Still, it was the only moral thing I could think of to do. I firmly believed that the war was unjust and that the slaughter it engendered was criminal. Nevertheless, I had a low lottery number, and it was certain I would be called up. I didn’t know whether I would go to jail, to Canada, or to basic training.

Then fate threw a knuckleball. When I took my draft physical, I was a scrawny twenty-two-year-old with a bad cigarette habit. I flunked the physical exam by reason of hypertension, a term I had never heard until then. Smoking may have saved my life. The strung-out hours of the night before might have had something to do with it, too. After the last of the poking, prodding, and palpating of the exam, a burly sergeant looked at my folder, glared at me, and said, “Mr. Dee-boyze, you have been examined and found unfit for service in the armed forces of the United States of America. Do you have any questions?”

I was astonished beyond words.

Two years later, I quit smoking and never touched tobacco again. Because I failed the physical, I never had to fight the big fight with my draft board, the military, my conscience, the Vietnamese, or my father, although he and I had other fights that were nearly as difficult. I was safe on multiple levels but also strangely condemned, as he was, to a sense of unease, an awareness of ambiguous fate, of a major test evaded. It wasn’t until I walked the trails of Nakai–Nam Theun that I began to see the lingering questions from those days as one of several strands of attraction that drew me to the banks of the Nam Nyang in middle age. There can be no equivalence between my present experience as an older man looking for wildlife and the road not traveled by my younger self, but I could not have been more interested to inhabit, however briefly, the general arena to which my country, once upon a time, would have provided me an all-expenses-paid yearlong tour. My search for saola, at some level, allows me to touch that alternative past, which I was never obliged to live.

Drained by the previous day’s hard march, we pass a leisurely morning in camp. I find a sunny spot on a ledge of river rock and catch up on notes. Soon Bone and the other young Sek boys settle next to me to play a game of cards, and minutes later Mok Keo is looking over my shoulder and pointing out individual letters as I write them. The boys temporarily suspend their game to attend Mok Keo’s play-by-play description of the symbols appearing at the point of my pen. Five curious heads cast shadows on the page.

My penmanship is deplorable, but I am printing in capitals, so the letters are legible. The boys, if they are literate at all, would know only Lao script, which is as different from the Roman alphabet as the writing systems of Arabic and Chinese. Mok Keo, however, was educated in Vietnam and is literate in Vietnamese, which uses a modification of the Roman system. He knows his ABCs, and he’s telling the boys how they work.

It sounds as though he is offering a kind of narration, but he cannot know the meaning of the words I am writing. Perhaps he is telling the boys generally about writing and its purposes; perhaps he is imagining what kinds of things I might be recording. The boys are rapt initially, but soon their attention slackens. So does Mok Keo’s. My printing is small, and he signifies he’s having eye trouble. He is probably nearing fifty, and if he were more concerned with reading or other small work he would doubtless need reading glasses. I hand him mine to try. He puts them on and immediately feigns great dizziness. Now Thong Dam tries them on, followed by Bone and the others, each one reeling, to the delight of his friends. Returning the glasses to me, they squat and again watch me write, evincing amusement but not envy. Had I been cleaning a large fish, I expect their attention would have been the same.

Ours is a happy camp this day: plenty of food last night, good fishing in the river, fine weather, and a comfortable campsite beside a beautiful, murmuring river.

Robichaud devotes the morning to organizing his specimens and bringing his field notes up to date. Simeuang has counted our haul of snares—more than five hundred so far. Our plan is to survey a couple of nearby streams this afternoon, but for now, Robichaud decides the time has come to document the expedition with a photograph. He calls everyone together on a midriver ledge. The Ban Beuk boys kneel in a line with the snares piled before them. Robichaud places the head of the juvenile muntjac in front of the snares. Everyone else stands behind the boys. I will take the picture. The light is good, the composition balanced. I kneel to fill the top of the frame with sky. Everyone looks proud and fit. Solemnly I count in Lao, “Neung. Song. Si!” As I press the shutter, riotous laughter breaks out. “Saam! Saam!” they call. “Three! Three!” I have blundered. In the concentration of the moment, I counted, “One. Two. Four!”

It is a good picture. It shows my miscount bringing mirth to the faces, smiles beginning to blossom.

Back row, left to right: Mok Keo, Olay, Touy, Viengxai, Simeuang, Phaivanh, Robichaud, Sone, Meet. Front: Kham Laek, Phiang, Bone, Thong Dam. Snare wires and head of juvenile muntjac in foreground.

Robichaud, Phaivanh, and I will go up the side creek that runs through camp, looking for sign of saola. Simeuang, Touy, Olay, and Sone will hike one drainage farther upriver and do the same.

We have scarcely started when we come upon the remains of yet another poachers’ camp. It lies well hidden, back from the river, and has not been used for a long time. It features a crib of stout poles, intended for live porcupines. “Sometimes they set their snares with insulated wire, so that they cause less injury,” Robichaud explains. Stuffed in a bag, porcupines are easy to transport, and they are worth more alive than dead, fetching high prices in the restaurant trade in both Vietnam and China. Robichaud adds that the manifests of ships plying the Vietnamese coast in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries mention eaglewood, turtles, and rhino horn. “The trade in wildlife and precious wood is nothing new,” he says. “It’s just that now we are seeing the particular ugliness of the endgame.”

While Robichaud and I go up the creek bed, Phaivanh, wearing his Statue of Liberty T-shirt, will flank us, checking the canyon side on the left for snares. I watch him go. His feet clad in flip-flops—I doubt he has worn a shoe in his life—he ascends the sheer slope, each step with equal strength, each foot placed exactly, always in balance, always with the same poised ease, whether moving forward or stepping back to avoid an obstacle. Walking and carrying loads are among the most mundane activities in life, but some people are better at them than others. The Sek and other residents of Nakai–Nam Theun acquired wheeled vehicles only a few years ago, when hand tractors and motorbikes arrived. And while they have long harnessed water buffalo to plow their paddies, they have never used pack animals. Every kilo of rice harvested from their mountain swiddens is carried homeward on their backs. The same may be said for every house post and bundle of thatch, at least until recently. From a young age, someone like Phaivanh would have walked miles every day in the forest, often bearing heavy loads. His ingrained skills are marvelous to behold. I can no more duplicate his grace in this terrain than I might match a Puebloan cliff dweller on the scarps of Mesa Verde.

This nameless stream is as flood-scrubbed and precipitous as the tributaries of the upper Nam Nyang. It holds few patches of mud or sand that might record a track. Still, it seems more promising. Robichaud says it smells right. To my eye, it closely matches the backgrounds of the few photographs of saola that camera traps have caught. The relative dimness, owing to the thickness of the canopy, seems to equal the dimness of the photos. Also similar is the ubiquity of horizontal vines, which, in defiance of gravity, extend laterally and improbably across the streambed like cables. Here the usual palette of greens has shifted toward gray, as though the foliage and rocks in this dank place achieved a kind of kinship. Whatever the secret of the creek may prove to be, we push on with anticipation, climbing a headwall and the ledge behind it, and another headwall and ledge, and on and on, like mice on a staircase.

An hour passes, and finally we face a dripping, moss-hung wall of rock that is double the height of those we’ve already scaled. Robichaud owl-hoots to Phaivanh, who comes sliding down to the creek. Phaivanh and I will wait here while Robichaud goes ahead “to see if there is anything worth checking out.” His foray will be solitary and silent, the kind of reconnaissance he prefers.

A slow rain of leaves trickles from the canopy. A barbet chants tookaroo. The forest vibrates with an insect clatter that is like the rattle and whirr of a chain-link assembly line, as though an infinitude of gadgets were being manufactured. And indeed they are: stems, beetles, grubs, leaves, centipedes, eggs, nymphs, molds, turds, photosynthesized sugars, microstomatic exhalations of oxygen, and ten thousand things more. The ecofactory is running full bore.

Phaivanh and I exchange smiles, which, in the absence of a common language, is about all we have the capacity to share. I wonder about his prospects. He is a subsistence farmer, a quondam guide, and a militiaman. He can stay in his village or he can emigrate to Nakai or the poorer quarters of Vientiane. He is a good-hearted and capable fellow, and if he weren’t working for us he might as easily work in illegal logging, the wildlife trade, or rosewood smuggling. He likely has dabbled in one or all of these areas already. There are surely other alternatives unknown to me, but not many. At this moment, Phaivanh is the master of an AK-47 and a fifteen-bullet clip. He cleans the surface of his weapon with a corner of his shirt and a spit-moistened twig, which he has chewed into a kind of brush. He picks out grime from the rifle’s deepest crevices with the weirdly long nail of his little finger, which, like many of his countrymen, he cultivates for deep and satisfying scratching of the inner ear.

On one level I feel as though I am being held under guard. Phaivanh understands that a central element of his job is to keep me out of trouble. On another level I am more than content. Lazing in a pleasant woods has always been a source of consolation. From the age of twelve onward, I went into the woods behind my house every day after school to have a smoke. A log and a granite boulder made my easy chair. The L&Ms and Tareytons I stole from my parents only partway salved my adolescent insecurities. The calm of the trees, the aroma of leaf litter, and the random sounds of wind and water helped with the rest. So it is now in this forest, as long as we sit still and I am not reminded at every step that the forest and I are strangers to each other.

Robichaud returns. Unfortunately, he has found nothing. No Schismatoglottis and no tracks in sand or mud, for there is only stone in the stream channel and leaves and roots on the sides. It is a typical day surveying for saola. We seek the exceptional, the one in a million, the lottery jackpot, and we get the ordinary—a precipitous, rockbound stream in a merely beautiful mountain forest.

Departing the creek by the north wall of the canyon, the side that Phaivanh did not inspect, we soon encounter a snare line that must have been a monster to build. The steepness of the slope would have doubled the physical effort necessary to chop and pack the barriers and install the snares. As the Lao say, the Vietnamese know how to work. Both the Lao and the Cambodians are farming people. They are the Indo part of Indochina. The Vietnamese are the other part. They have more in common with their loved and hated Chinese neighbors to the north, who excel at trade and entrepreneurship.

The French noticed the difference between the two groups in the earliest days of colonization. The Lao refused to be good slaves. They might work for themselves, but they wouldn’t work for European overlords. In frustration, the French imported Vietnamese into Laos to build a cadre of bureaucrats and overseers who would crack the whip on the peasantry and help squeeze wealth from the country.

And the wealth is still being squeezed, although it is now carried off in new pockets. The government of Laos continues to pay Vietnam reparations for the costs Hanoi bore when it “liberated” Laos from US-backed royalists in the 1970s. In addition, the relations between the two countries feature business concessions and sweetheart deals of every stripe and color, lopsidedly benefiting Vietnamese interests. The same may be said for relations between Laos and China, whose hunger for minerals and timber is without limit. That’s at the macro level. At the micro level, the squeeze continues in places like Nakai–Nam Theun, in territory that nominally belongs to the Lao nation but effectively serves Vietnam as a collection ground. The ubiquity of snares and hacked rosewood stumps in the Nam Nyang watershed, to say nothing of the existence of the Rosewood Highway, bear the proof. They testify to the permeability of the border and to the unequal flow of wealth across it. In particular they testify to the nearly superhuman energy and industry of the men who build the snare lines, often in the rainy season, under conditions of astonishing hardship. They also testify to the utter absence of sympathy for wild creatures.

No doubt the poachers, or at least most of them, enjoy a beautiful sunrise as much as anyone. It may even be that they rejoice to hear a chorus of gibbons or the bark of a muntjac, and not because it betrays the location of game. I grant that they may delight in the music of the forest, yet this wins the creatures of the forest no reprieve. The fact remains that the situation is dire. The harvest of wildlife is indiscriminate, wasteful, and relentless. No one for a moment can believe that it is sustainable. We may sympathize with the poachers as individuals—they are poor; they work; they strive—and still blame the soulless system in which they work; we can acknowledge that the familiar rationalization “If I don’t do it, someone else will” probably comforts those who regret cruelty while committing it; we can lament the pervasive belief that nothing can brake or halt the inexorable consumption of the forest and so to hold back is only to penalize oneself; but the net effect is that in this place, at this time, not the least shred of a conservation ethic operates in favor of wildlife. The result is a powerfully lethal combination: a dedication to work that would put pious Calvinists to shame yoked to a valuing of nature that counts only dollars and cents, yuan and dong.

A scan of world headlines attests that this bane afflicts places far from Southeast Asia, but Southeast Asia is surely its center. The hunger of the region for exotic flesh—for ivory and other animal parts deemed precious, and for the bones, fluids, and tissues of wild creatures to provide cures, real and imagined—has now spread to some of the remotest recesses of the world. Informed people know that the pursuit of blood ivory threatens the survival of elephant populations across broad swaths of Africa, but few have heard that jaguars in Guyana, in South America’s north, now also feed the craving for big-cat qi in a growing Chinese colony there. This kind of hunger, to be fair, is not unlike other consumer hungers that draw substance from the planet and leave desolation behind, but it is redder in tooth and claw, for it literally tears flesh and spills blood.

In Vietnam I heard it said, as a point of pride, “We will eat anything with four legs except the table!” Ha-ha-ha. That’s a good one. Pass the beer.

One day Robichaud and I had lunch in an open-air restaurant at a crossroads near the Mekong. We watched trucks and buses, in a blue diesel haze, make the turn onto Highway 8, bound eastward toward Lak Xao and Vietnam. The loads were heavy, the traffic constant. Then an enormous flatbed came from the opposite direction, from Vietnam, rattling and grinding to a halt. The driver parked it just outside our restaurant. “Do you know what that is?” asked Robichaud.

I did not. The truck was unremarkable, its load no more than a mass of empty cages, each a cube about three feet on a side, stacked two high and three wide the length of the bed.

“It’s a dog truck,” he said. “It’ll load up in Thailand with strays, kidnapped pets—whatever its people can find or steal—and head back to Vietnam. Each of those cages will be jammed with terrified mutts, which will be sold for restaurant food.”

We had just come from the market in Ban Namee, a small community beside the highway, where we browsed a modest selection of comestible and pharmacological wildlife. There were plucked bulbuls and mouse-deer hooves, dried geckos and a pile of bats. There were gaur teeth, monkey hands, and owl feet, all authentic. The biscuit-size squares of elephant skin may have been genuine, too, but one wondered about the tiger teeth, at one hundred dollars each. The rhino horn, price unknown, was undoubtedly fake. One limp corpse looked like a black bobcat in a furry cape: a giant flying squirrel, said Robichaud.

Whether the object of desire is a tiger penis, dog flesh, or a Tiffany diamond, the craving that makes it valuable goes back deep in time to hungers that transcend need. The early Greeks knew something about this. They had a story about ravening hunger, as they had a story about nearly every theme and subject. The protagonist in this case was a Thessalian prince, son of Triopas, who was named (not mellifluously) Erysichthon (pronounced “Erees-ick-thon”). It is fair to think of his tale as a parable of consumerism.

Because Erysichthon wantonly felled trees in a grove sacred to Demeter, the Earth goddess avenged herself by sending Famine to sleep with the young prince. As Erysichthon and Famine embraced, Famine breathed her bottomless emptiness into him. Thereafter Erysichthon had an appetite that no amount of eating could sate. He ate through the storerooms of his father, the king, and when they were exhausted, he sold his own daughter into slavery and used the proceeds to continue feasting. Here one story intersects with another. As a result of other dealings with the gods, Erysichthon’s daughter became a shape-shifter and managed to escape her enslavement. This worked to Erysichthon’s benefit because now he was able to sell her again and again, and she would escape each time. Erysichthon’s story exists in multiple variants, but Ovid, in Metamorphoses, tells us that eventually the deception with his daughter wore out, and Erysichthon was reduced to beggary. Even then his cravings did not die. With nothing else to feed him, he gorily tore into his own flesh and devoured himself, perishing not from hunger but from appetite.

At the top of the slope, the snare line we have been following crests the ridge and continues down the other side. No animal traveling the ridge can fail to encounter it. Robichaud and I pause at one sprung trap to examine a snared silver pheasant, a male in glorious plumage, its feathers a speckled snowfall beneath the corpse. Phaivanh starts down the other side, still following the line, collecting every wire noose. Soon he calls to us, with urgency.

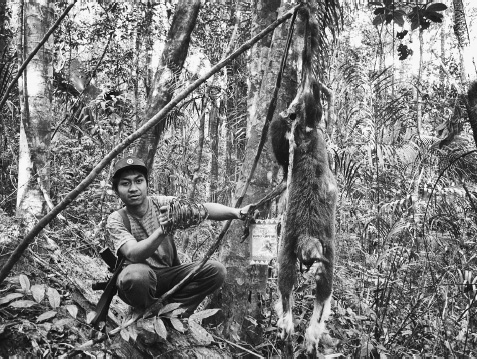

He stands beside a red-shanked douc (also called douc langur), snared by one foot, hanging upside down. The limp hands reach vainly for the untouchable earth. The monkey has been dead for several days, possibly longer. Scavengers have torn away the fur and eaten one leg to the bone.

Like saola, red-shanked doucs are endemic to the Annamite Mountains and adjacent lowlands. Doucs range much of the length of the mountain chain, exhibiting intriguing but poorly understood color variation—black-, gray-, and red-shanked forms—from south to north. The adaptable rhesus macaque may travel the world in cages and inhabit many a zoo and testing laboratory, but maintaining a douc separate from its habitat requires competence that few institutions possess, so not many are found in captivity. Nevertheless, fashion designers should note that few creatures in nature, and certainly no other primates, dress with more flair. The basic suit of the douc is gray flannel, with a cape of black. Among the red-shanked, the trouser legs are the color of a Williamsburg brick. The fingers are black, but the hands and forearms are white, an elegant touch giving the appearance of long, fingerless gloves. The tail and rump are cream-colored, and the pretty, snub-nosed face, framed by a white beard and black headband, is mango orange, the color of a dessert.

Doucs are leaf eaters and lead an almost entirely arboreal life. The carcass in the snare before us testifies to the peril of a visit to the ground. The spring pole of the trap that killed the douc is thick, powerful, and tall, and when the monkey stepped into the snare, it must have whipped him into the air as though he were a minnow jigged on a salmon line. If he was lucky, his spine gave way and the snap killed him, but this was probably not the case. There are few vertebrates more supple than a douc, which even by the standards of monkeydom is lank and long-limbed and moves as though made of rubber. Probably the animal bobbed at the end of the wire for a long while, and kept bobbing as he clawed at the metal tourniquet that had seized his ankle. His shrieks would have caused the rest of his tribe to draw near. Perhaps they gathered in the trees above, chattering anxiously, faces contorted with worry. One or two might have come down and gingerly touched the victim, trying to understand his plaint or even comfort him. Perhaps they, too, picked at the wire.

I wonder if at some point the douc managed to right himself and perch atop the spring pole to which he was tethered. The maneuver would have required spectacular athleticism but, once the animal’s panic subsided to a dull roar, maybe it was possible. Balancing on an unsteady stick, however, would have been expensive in energy and concentration. Eventually the tribe moved away, to feed or sleep for the night, and unquiet darkness fell. Pain, exhaustion, and sleeplessness then took their toll. Fear was constant. The moment had to come when the douc could no longer hold on, and he toppled from his perch to hang inverted, gravity working his heart and veins the wrong way, the legs drained, the head gorged. Slowly, too slowly, dehydration and hunger eroded consciousness and pulse, a torture like the martyrdom of a saint at the hands of especially creative centurions.

Phaivanh with snared red-shanked douc.

Robichaud is cursing, stamping around, visibly moved. He’s not distraught, exactly, but he has acquired a molar-grinding intensity. He retrieves a tiny video camera from his pack and records the scene, narrating the ghoulish details: “Particularly sad… a douc langur… listed on the IUCN Red List as globally endangered… usually arboreal, this one came to the ground for something and was caught in the snare and hung here until it died.”

Phaivanh has found a scrap of trash nearby. It is an empty package boasting MENTHOL CANDY. A few words are printed in English, but most of the lettering is Vietnamese. The brand is Hanoi Capital. We are days of travel from the nearest village, much too far for local hunters to have come to set snares, and if any question remained about the Vietnamese origin of the men who built—and then abandoned—the snare, this bag is a kind of signature. We take pictures of the douc while Phaivanh prevents it from spinning. Robichaud is now silent. His narration and picture-taking finished, he has plunged deep into himself. Abruptly he stows the recorder in his pack and heads downhill, moving fast.

But it doesn’t seem right to leave. The douc, a cousin primate, is still dangling. Should we not cut him down? But I have nothing to cut the wire with, and the spring pole is long, the junction of wire and pole too high to reach. Phaivanh is watching me the way a border collie watches a problematic sheep. He will not leave until I do, although he would certainly like to get on with things, gather the rest of the snares, and finish our patrol. I try to remember the Lao word for machete, thinking we could hack down the spring pole, but I cannot summon it. Besides, I don’t think Phaivanh is carrying anything but his Kalashnikov. I am at a loss, also tired and hungry, an observer without tools. I take a last look at the douc and glumly follow Robichaud down the slope. Our failure to cut down the douc nags at me—it nags at me still—although I have no idea what I would have done with him once I had him on the ground. Just stretch him out and leave him? Perch him in the fork of a tree? Take him away and hide him, so that anyone returning to check the snares would get no benefit from his skull or hands or genitals, if he still had them?

Our small party is silent on the descent to the next creek and thence to the river, but my mind is churning. Mentally I compose an imagined letter, which grows into a report. Even as I hop boulders and dodge holdfast vines, I am cobbling together—and trying to hold in my memory—the sentences and paragraphs, then whole pages, calculated to alarm the International Environmental and Social Panel of Experts, the Independent Monitoring Agency, the managers of the WMPA, the World Bank, and the readers of The New York Times. I lay out the gravity of the cruel war on wildlife being waged in Nakai–Nam Theun and the extreme and poignant threat it poses to one of the richest concentrations of biodiversity on the planet. I persuade myself that if I set out the facts accurately and eloquently, infuse the argument with vigor, and build it step by inexorable step, the decision makers will finally and meaningfully take action. I see matters in sharp definition: the sequence of points to be made, the multiple elements comprising a solution, the ultimate benefits of a secure, well-patrolled protected area. I feel saturated with ideas.

Then we reach the river. We pause by the murmuring water. The air feels soft, the shadows cool and long. We rest, drinking deeply from our canteens. Gradually, cooling and rehydrating, I remember how the world works.