March 12

Nakai

Mr. Phouvong, Olay’s ever-smiling uncle and the proprietor of the oddly named Wooden Guest House, refuses to let us pay for our lodging these past three nights. Poised on his wrist like a hunting hawk is the enormous green moth I discovered this morning on the wall beside my door when I went out to test my step.

Robichaud and I have used our rooms rather hard. I have cleaned up the evidence of illness as best I can, but the pile of soiled towels and linens will surely dismay the housekeeper. Robichaud, for his part, has endowed his room with a powerful stink, having filled the closet with biological specimens in various stages of decay, including the skull of the juvenile large-antlered muntjac that fed our crew on the Nam Nyang. Despite Mok Keo’s efforts to rid the head of brains and flesh, it has turned maggoty.

Robichaud remonstrates with Phouvong, insisting that we pay, but Phouvong, deeply grateful for Robichaud’s tutelage of Olay, makes a shallow bow and says payment is impossible. The struggle is quintessentially Lao: two people bent on outdoing the kindness of the other. Phouvong wishes us well, shakes hands, and walks away, gazing fondly at the insect on his arm. Man and moth make a curious tableau. “Lao falconry,” Robichaud quips, and Phouvong, still admiring the moth, closes his office door.

The moth was the size of a small bird, fully six inches from wing tip to wing tip. I measured it with a ruler. The four delicate wings (two fore and two aft) were nearly translucent. Each had an eyespot that peered toward the furry thorax. Most exquisite were the fan-shaped antennae, a lattice of orange filaments that stood out from the head like solar panels from a satellite. After my initial surprise at seeing it on the pale red bricks beside the door, I wondered what message it might bear.

I suspect that Mr. Phouvong read the arrival of the moth as a friendly omen, a harbinger of luck, as did I. In the extremity of my sickness, crawling from bed to toilet, I had thought of my wraithlike friend Mary, who wrote in my notebook, “Just call for me if you need a guardian spirit.” When I was lowest, I sent her a mental scream. The frail moth seemed her reply, a gift of beauty and reassurance. Yet I worried, too, that it might be a dispatch from her departing spirit, signaling her death. While in Nakai I had heard from Joanna that things were well at home, but there was no chance of a quick reply to any query I might send now. Within hours we would be across the reservoir and again beyond the reach of messages. I packed my gear feeling light and heavy at once.

At the boat landing, Simeuang enacts a metaphor of saola conservation. The boatman has gone to fetch the motor oil he forgot, and while we wait Simeuang fishes, in vain. His casting net, a purse seine, is different from the nets the guides dragged through the water of the Nam Nyang. It has a light chain around the skirt, which sinks the net, dropping a dome of nylon mesh around the fish—if only a fish were there. When it settles, Simeuang pulls the lanyard of the net, which closes the skirt, and hauls it in. He sees it is empty and patiently casts again. And again. Robichaud says he has watched thousands of such casts and witnessed the catching of only one or two fish. But those who are fishermen to their hearts, as Simeuang is, keep casting.

Our trip up the Nam Mon is another long cast, too—for saola—and we set out in a chak hang that is dangerously small and overladen. We have scarcely a knuckle’s worth of freeboard. A significant swell would swamp us, but for now the lake is glassy and flat. We roar on, or try to roar. Periodically the engine coughs and nearly quits. The boatman is impassive. We have three hours to go.

It turns out that even before the MacKinnon expedition to Vu Quang in 1992, knowledge of saola was not always restricted to the Annamites.

The Dong Son people, who occupied Vietnam’s Red River delta during the first millennium BCE, decorated their exquisite bronze drums with images of people and animals. Among these animals is a deerlike creature with long, straight horns. It appears to be a saola.

Roughly contemporaneous, the Sa Huynh culture prospered farther south, in central and southern Vietnam. They were evidently seafarers, for archaeologists have detected their presence even in the Philippines, on the far side of what the Vietnamese call the East Sea (and most US atlases call the South China Sea, an abominable term from a Vietnamese point of view). Notably, the Sa Huynh cremated their adult dead and buried the ashes in large jars. The grave goods recovered from such jars feature glass and stone beads and, in the late stages of the culture, jade ear pendants, which were probably worn by influential or ritually important men. The pendants are the only representational artwork known from the culture. They depict matching animal heads that face outward from the point of attachment to the ear. The animal, which is apparently always the same, has a deerlike face and possesses long, pointed horns. Some say it represents a saola.1

Even in modern times, a glimmer of the existence of saola flashed on the wider world. In 1912, the lexicographer Théodore Guignard published his Dictionnaire Laotien-Français, in which he listed the word saola as “species of antelope, antelope of the rocks.”2

Then for eighty years, beyond the confines of saola habitat, the word and the animal were forgotten.

The motor has quit again, and as we drift upon the lake, the boatman sucks and siphons it back to something approaching life. Finally we stammer across the remaining flat water and up the broad, drowned Nam Xot, beaching at the sprawl of Ban Nahao. We pile our gear onshore. Our immediate destination is Ban Navang, on the Nam Mon, the next drainage southeast. Again we will send our goods ahead by tractor or motorbike, and we will follow on foot. Simeuang and Olay will make the arrangements. Robichaud, as usual, has a call to make.

He directs the boatman to cross the river to a set of steep bluffs, the landing for Ban Thameuang, a hodgepodge of resettled Vietic tribes. Robichaud wishes to visit a friend.

Ban Thameuang is a village built on a complicated mix of values and emotions. Shame is one of them. The mavens of world economic measurement have long termed Laos “underdeveloped,” “least developed,” even “primitive,” a word rarely spoken but often thought. Laos ranks low in all the conventional indices of material progress, from adult literacy to televisions per capita, and it is cushioned from the abject bottom only by an unfortunate few nations that include its regional neighbor Cambodia and the failed states of sub-Saharan Africa.

A low position on the ladder of economic advancement easily translates as backwardness, and the shame of backwardness breathes its infection into one of the least ventilated corners of Lao national life—the treatment of “ethnics.” In conventional thinking, backward people hold back the nation to which they belong. They score low on the metrics of modernity. They hobble their country’s advancement.

In order for the state to progress, so the argument goes, such people must be hauled from their dim pasts, by force if necessary, and brought into the enlightening glare of modern life. They must be persuaded to live in proper houses, and they must learn to grow rice and own things. Ultimately, like everybody else, they need to hunger for cell phones, motorbikes, televisions, and even “jobs.” This, at least, is what a Lao official might be inclined to think after he has been snubbed at yet another international meeting, viewed as representing a weak sister among the giants of the world, a country that is less a nation than a melting pot of ancient ethnicities. Such thinking can color a government’s treatment of its least modern people.

The other side of the coin, of course, is that Laos is a world leader in cultural intactness, linguistic diversity, and the preservation of ancient ways of life. Such qualities, unfortunately, are rarely measured and less often ranked. Counting TVs is easier.

The Sek and the Brou grow paddy rice, which is a mark of relative advancement, but they also create swidden, a practice generally deemed backward, and so they somewhat contribute to the belittlement of their country. The “worst” offenders, however, are the Yellow Leaf People, those who wander the forest shunning agriculture in all but its most rudimentary form, the people whom anthropologists term “nomadic foragers” or “hunter-gatherers.”

The term Yellow Leaf People has a revealing etymology. In the forests of Laos, nomadic foragers typically roof their temporary shelters with palm or banana leaves, but they rarely stay in one place for long. By the time the leaves turn yellow, they have moved on.

On one occasion, a colleague said to Robichaud, it was “very embarrassing” to have people “living in the forest.” Another official, elsewhere in the government, asserted, “These people have a right to be civilized!”

“A right?” Robichaud replied. “Translocation is killing them. What good is civilization going to do for them if they’re dead?”

The resettled misfortunates of Ban Thameuang include remnants of several Yellow Leaf tribes. One of these is the Atel, who formerly roamed a portion of the upper watershed of the Nam Xot, deep in saola country. They neither built villages nor accumulated goods. Each day their principal occupation was to secure the food they would eat that day. The next day, and every day, they did the same. For ten months of the year they slept in palm-leaf shelters that were little more than lean-tos, and every few days they would move to a new location, across a ridge or up a canyon, to see what food they might find. Only in the depths of the rainy season did they root themselves in place, with sturdier huts, to last out the worst of the weather.

Probably no one outside Ban Thameuang knows for certain how many Atel survive—certainly less than two dozen, perhaps half that, which renders them at least as endangered as saola. By means unrecorded (I heard the word “captured” in one account; “encouraged” in another), the government caused them to relocate to Ban Thameuang in the late 1970s and 1980s. At the time, the traumas of war and revolution were fresh, and the new Lao government was anxious to consolidate control of its people.

Among the Atel who came to Ban Thameuang were an elder known as Touy (another Lao “Chubby”) and a younger man named Bounchan, who by the mid-2000s was “fiftyish.”

In 2006, Robichaud arrived in Ban Thameuang and asked Touy and Bounchan to take him to the Atel homeland, in the headwaters of the Nam Xot. Robichaud would cover the expenses. They readily agreed. Like the rest of their people, Bounchan and Touy relished any opportunity to go home.

Going home meant being able to honor their ancestors with offerings of food and tobacco in exactly the places where such honoring was most meaningful. It meant gathering rare herbs and longed-for foods. It meant contact with the place spirits that knew every Atel person individually, spirits that were the guardians of Atel culture and resided where each person had been born.

Robichaud, Touy, and Bounchan traveled by boat for a day up the Nam Xot until impassable rapids stopped them. Then they walked along the river, eventually branching up a tributary, the Houay Kanil (houay means “stream”). They visited a gemlike waterfall, swapped stories, and roamed the country. Robichaud surveyed for wildlife, as usual, but was no less interested in learning how a small band of people possessing almost nothing and speaking a language known to no one else once inhabited their territory. For three days at the headwaters, Touy and Bounchan introduced Robichaud to the world they had lost. They came to a pomelo tree, a variety of citrus, growing beside a big rock. They sat and ate pomelos (which taste much like grapefruit), and Bounchan said, “This is where my old uncle, who planted the tree, would sit and eat the fruit, just as we are doing.” Touy and Bounchan told Robichaud how the Atel used to use the bark of a certain tree3 as a poison, throwing it into pools to kill fish, which they collected and ate, and they told how they pounded the tree bark into sheets that they wore as clothing, because whatever toxin killed fish also kept mosquitoes away. One day Robichaud witnessed Bounchan kindle a fire starting with nothing but a knife. First he found a certain kind of dead, hard bamboo and split a length of it in thirds. He bored a hole through two of the pieces and placed tinder between them, making a kind of sandwich. While Touy stood in the background offering advice, Bounchan wedged the third piece in a notch in the trunk of a tree to hold it fast and sawed the sandwich back and forth against it. In moments the tinder began to smoke and then to flame.

Bounchan said that when he was young, the only metal known to anyone was a single machete shared among twelve families. He recalled that the big knife was especially useful when they built shelters for the rainy season.

He and his people roved the forest, always on the lookout for scavenging birds. A raucous flock of crows might show where a pack of dhole had made a kill. People would rush there and with spears of sharpened bamboo drive off the wild dogs. (They lacked bows and arrows.) They would take the carcass, leaving a leg or some other portion as an offering to the pack. They would do the same with a bear’s kill or even a tiger’s. Every day the paramount task was getting food, and the Atel had many ways to get it. Few plants or animals escaped their attention, and they could make a meal of tubers or termites with equal ease.4

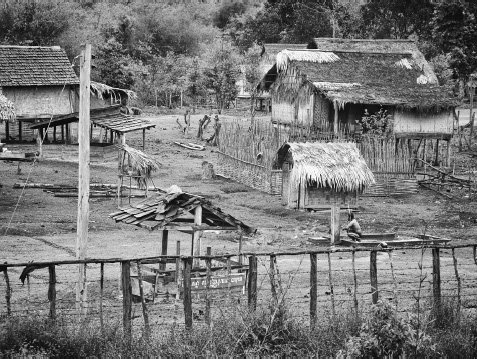

Bounchan is now dead, a few years gone. It is Touy whom Robichaud has come across the river to see. He brings photographs of the now distant trip to Houay Kanil, and gifts of food as well. We tie the boat at the foot of a tall bluff, said to be the approach to Ban Thameuang. The trail is indistinct and fiercely steep; with difficulty we scramble up the sandy bank. It is the heat of the day, and the village bakes on its barren plain above the river, a shamble of dwellings and hacked stumps. Not a soul stirs. No children call or play, and not even a cur comes forward to bare its teeth. We approach a sleepy-looking house, and Robichaud calls out, asking for Touy.

A woman’s voice answers from within the doorway, “He has been sleeping in his swidden. I don’t think he is here. But you can ask his niece. She lives over there.” An arm projects from the door, pointing.

The indicated house boasts a few scraps of sheet-metal roofing, the only metal on any house in view; the rest of the roof sags under aging thatch. The walls are mats of bamboo, woven in diverse patterns. The house perches on skinny stilts and lacks a porch. Its flimsiness and the several small pigs asleep beneath the entry ladder bring to mind the children’s tale of the big, bad wolf, who huffed, puffed, and blew down shacks like this.

Again Robichaud addresses the darkness beyond the doorway. We are invited to enter, but the ladder is spindly, and I fear the frail rungs will not bear my weight. I climb with my feet at the edges, near the dubious support of the rails. Inside is no better. Broomstick poles and cracked slats comprise a floor that is as much holes as wood, as much gap as substance. Robichaud settles himself carefully. I am a little heavier, certainly clumsier. Were I to lurch sideways, I might fall through the wall. I pray we do no damage to this structure.

Touy’s niece sits with her infant son beside the pool of light spilling through the doorway. Her husband, shapeless in a dim corner, reclines on a pile of bedding. He seems to nod to us, perhaps lifts a hand (my eyes have not adjusted to the dark), and does not further stir. The clay hearth behind the niece is cold on this hot day, but everything within the hut—quilts, clothes, baskets, and walls—is tinged with soot. There are no windows, only the doorless entry. Myriad pinpricks of light, like a crowded galaxy, leak through the wall mats.

Yes, says the niece, Touy is at his swidden. She has a pleasant smile. Her mahogany skin is lustrous. Her uncle, she says, is unlikely to return soon.

Robichaud asks about the baby, and she holds him for us to see, a toothless, grinning, jolly fellow in a dirty brown shirt. He might be seven or eight months, old enough to be amused by odd-looking, whiskery, pinkish strangers. The child is plump, but his mother says he has been sick, shitting water for three days. She doesn’t know what the matter is. He is her only child. She had another baby a few years ago but lost it.

Touy’s niece speaks Lao haltingly. Even I can tell it is not her native tongue. She might be within a few years of twenty, which would put her among the first generation of Atel children born in Ban Thameuang. I cannot see any food in the house, although surely there must be some.

All that the outside world knows of the Atel would fit in a small notebook—some scraps of language, a pittance of lore, almost nothing of their cosmology. Among the few items that have been recorded is their belief that wild foods and domestic foods must not be eaten at the same meal.5 To mix, for example, ant eggs and rice at one sitting would be poisonous, and if the combination did not finish you on the spot, it would cause much suffering. The resettled Atel of Ban Thameuang walk a perilous line in their striving for subsistence. They grow rice, cassava, and other crops, but not enough to live on. Some of them labor for the Brou of neighboring villages, who work them hard for meager pay—sometimes rendered in kip, sometimes in opium, which the Brou get from the Hmong to the north. The Atel also forage as best they can, but the land near Ban Thameuang, unlike their lost homeland, is continuously scoured by many hungry eyes, leaving little to be found. The Atel do not prosper. They fall ill in body and soul, and they die young.

In at least one place elsewhere in Laos, the government allows other clans of Yellow Leaf People to continue their nomadic ways, even providing depots of food to help them through times of shortage. But NNT lies in Khammouane Province, where the authorities prefer their people planted, like rice, in fixed places. Again, the correspondence between NNT and the nineteenth-century American West bears noting. Ban Thameuang recalls the early years of American Indian reservations, where lives were also short and heartbreak epidemic.

Robichaud shows Touy’s niece photographs he took of her uncle on their 2006 journey to Houay Kanil. She smiles appreciatively, perhaps out of politeness. It is not clear to me that she reads the photo as a photo, which is a knack no one is born with. Surely she has seen few such images before, and the first view of a relative reduced to an inch-high image on a piece of photo paper is not always comprehensible. Robichaud also gives her candy and a few packets of dried jackfruit and other edibles. She asks him what to do with the contents of the packets—plant them or eat them? Robichaud explains that they are food, not seed. We prepare to go, and as I stand on stiff legs, bent low beneath the roof, I am again fearful of stepping on a weakness in the floor or of having to grab a door frame that cannot stand a tug. The kindly niece and her ailing son watch us as they might watch water buffalo lumber away. They are patient and calm of gaze. Much like Martha, the saola, in her grotto in Lak Xao, they live in a place not of their choosing, subsist on a diet as foreign as moon rocks, and are observed by outsiders, like Robichaud and me, in their naked vulnerability.

Electricity is coming to Ban Navang. Lines of bare poles angle through the village, soon to be wired to a small hydroelectric generator on the river and soon to enable a long-awaited inrush of modernity: pumped water, refrigeration, lightbulbs, cold beer. It is already sundown. We overlook the village from the second-floor veranda of the new WMPA building and witness one of Ban Navang’s last journeys into natural darkness. The roofs are a mosaic of old thatch, blackened with age, and new thatch, yellow and plump. A man in blue undershorts squats to bathe at a fountain. The usual dogs bark. The expected boom boxes, powered by solar chargers, tangle their songs. Hills rise into the mist beyond the village, foliage stacked on foliage, a confusion of canopies smoothed by gentle light.

Ban Navang.

We traversed those hills not much earlier in a three-hour trek from Ban Nahao, at first zigging and zagging along the rims of dry paddies, then tunneling into the forest. The way was flat, the footing solid, the trees alive with sound. At every squawk or warble, Robichaud named the bird that made it: a racket-tailed drongo, a greater coucal, and many others. We lingered amid swiddens at a towering snag where a coppersmith barbet hammered out its tok, tok, tok, metronomic and unfading, two hundred identical toks, ringing like a copper bell.

It was a fine walk, made finer by drugs. Still weak from my rodeo of purgation, I indulged in a remedy that I hoard in my kit. It is intended for migraines but bows only to coca leaves and amphetamines as a corrective for hard hiking. It quells pain with large doses of aspirin and acetaminophen and adds a jolt of caffeine to keep the legs moving. I floated down the trail.

Climbing the hill in Ban Navang to the WMPA quarters, we met a Vietnamese trader on a motorbike. He was handsome and affable, sporting torn jeans and a mouthful of crooked teeth. He had putt-putted down from Lak Xao, in the north, ferrying his bike and goods across the Nam Xot. In Saigon and Hanoi, his countrymen make an art of overloading motorbikes. You see mountains of chicken cages and towers of cartons roped, bungeed, and delicately balanced on two frail wheels, with no outriggers or sidecars to keep the peace with gravity. The young trader who bantered with us was well along in the art. Nested basins stood like a radio dish above what was left of his taillight, and a brimming crate of pots and miscellaneous knives rode at the small of his back. Big wire baskets flared to either side, filled with buckets, cheap metal bowls, machetes, and the kind of gizmo clutter you see in a sale bin at a hardware store. The young man had the manner of someone easy to amuse who was no less practiced at amusing others, someone hard to threaten and harder to bluff, a man sharp in trade and ready to trade anything he had for anything else if only he might squeeze a margin from the swap. Buried in the hodgepodge of his side baskets were several wicker canisters, and I wondered whether a turtle or a pouch of dried monkey hands had found their way into one of them, or would soon. Despite all his goods, the only thing he might have had that we wanted was information about the traffic in wildlife in the villages where he traded, and we knew that was the one thing he would not sell. We bade him good-bye and watched him coast down the hill and disappear into the thatch of the village.

Our business this evening, after a meal of sticky rice and little else, is to visit the nai ban, or village chief, of the Ban Navang village cluster. A friend of Simeuang’s, a fellow employee of the WMPA, guides us in darkness to the house of Sai, the headman, down narrow lanes where the murmur of family talk drifts from windows overhead. Sai’s main room is crowded with sacks of rice and crates of Beerlao. Sai’s wife operates a little store, and they have returned this day from a buying trip to Nakai. We sit in a circle on the floor—Robichaud, Simeuang, Olay, and me, Simeuang’s friend, and nearly a dozen adults of Sai’s family, including a handsomely gaunt old man, a seeming patriarch, who sits next to me and watches me closely. My beard has grown in, and it is all white. I surmise that the old man sees me as someone as antique as he is.

New wires and light sockets are stapled to the rafters, awaiting electrification, but tonight three dim bulbs linked to a motorcycle battery are all that push back the gloom. The light glints on the eyes of several children who peer from behind rice sacks in the depths of the room and hide when we look their way.

Simeuang buys two large bottles of beer from Sai’s wife, and we drink in ritual fashion. Sai listens solemnly as first Simeuang and then Robichaud explain our desire to ascend the Nam Mon, our need for guides, and our intention to leave camera traps at the mineral lick. Sai is impassive but alert. He is perhaps in his late forties, square-shouldered, not big, but taut and solid, like a wrestler. He and Robichaud are old friends, having traveled together to the upper Nam Xot in 1997. He sits grave and patient, a Brou Buddha. When Robichaud appears to be finishing, Sai nods as though asking for more. At last Robichaud has nothing more to tell him, and after a long pause, Sai speaks.

He says he will provide the guides. He would like to send Phok, because it was Phok, two years ago in March, who saw a saola at the bend in the river, just before the poung. It was four o’clock in the afternoon, on a clear day, and after the animal fled, Phok and the rest of the party examined its tracks carefully. Phok, in particular, is sure the animal was a saola.

Unfortunately, Sai continues, Phok is in the forest on survey work and is not available, but there are other guides he can lend us who have been to the poung. It is an interesting area. A little farther along the river is the WMPA’s new ranger station, placed to keep an eye on movement across the border. And not far away is the grave of a Vietnamese border crosser shot dead by a Hmong hunter. The Hmong wasn’t supposed to be there, either—no one from outside the protected area is authorized to hunt within it—but people say that the Hmong regularly hunted the mineral lick and did not like competition. Since the shooting, Vietnamese have been scarce.

The second beer is empty when Sai returns to the subject of Phok’s sighting. Modestly he explains that he was also there, behind Phok, as they came to the bend of the river. Robichaud and I exchange a glance. This is news. We had not known Sai was among the group. Phok, he says, had a good look at the animal before it bolted, but Sai himself saw only a fleeting shape. Nevertheless, he examined the tracks, traced them with his own fingers, and he heard Phok describe what he saw while it was fresh. Phok is certain, and Sai believes him, that the creature by the river was a saola.