Both extract and all-grain brewers must remove spent hops before fermentation. Trub removal, on the other hand, is an option many homebrewers overlook. Hops are relatively easy to remove. For homebrewers, the removal of proteinaceous trub is not quite so simple and the relative benefits are debatable, but the potential for improving your homebrew makes it worthy of consideration.

Hops could simply be removed from the wort by passing the hot wort through a strainer on its immediate way to the fermenter, but simple straining is perhaps wasting an opportunity to remove the trub. More on this subject later.

A convenient method for infusing additional hop aroma and some flavor into the wort is to pass the hot wort and spent hops through a basketlike device to which fresh hops have been added. The basket, called a hop-back, also serves as a straining device for the spent hops. The effect of this configuration is to “hot-wort-rinse” hop oils from these hops. The aroma-producing oils find their way directly into the fermenter, where they add aroma to the finished beer.

Trub (pronouced troob) is mostly a tannin (polyphenol)-protein compound precipitated out of solution during the vigorous boiling of wort or cooling of the wort. Its formation is the direct result of boiling malt (with its proteins) and hops (with its tannins, though malt has some tannins too). The heat and the vigorous boiling action cause precipitation. The trub formed during the boil is called the hot break, and trub formed at cooler temperatures, the cold break.

There is about three times more hot break than cold break formed, but amounts can vary considerably. About half of the trub is composed of protein. The rest is bittering substances (some hop bitterness is lost to trub), polyphenols (tannins), fatty acids and carbohydrates.

The amount of trub that will precipitate out of wort is influenced by quite a few factors. In the boil it is desirable to precipitate out as much trub as possible. In all the brewing processes prior to the boil it is desirable to choose ingredients and processes that can minimize trub, whenever the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Factors that can minimize the potential for trub in wort are: malt quality (poorly modified malt will increase trub), mash filtration (oversparging and pH contribute more polyphenols from the grain husks), grind and mill setting and mash process (decoction mashing will reduce trub in boiling by formation and removal of trub during decoction boiling and mash filtration).

Factors that can maximize trub formation during the boil are: time of boil, density of boiled wort, amount of hops, use of Irish moss, degree of agitation and pH of wort. After boiling, how quickly wort is chilled influences the amount of cold break that precipitates out.

Remember, if the compounds are in solution to begin with and the brewer does not take steps to precipitate them out, the compounds remain in the wort during fermentation and will affect the character of the beer to some degree.

TRUB: ITS INFLUENCE ON FERMENTATION

AND FLAVOR

There has been no shortage of research and experiments performed by the commercial brewing industry and brewing schools. Their concerns have addressed the needs of commercial interests and their large-scale (larger than homebrewing) brewing systems and attention to fine differences. More on this perspective later, but for now, let’s take a look at some of the conclusions reached.

Fatty acids in trub appear to serve as nutrients for vigorous yeast activity, increasing the rate of fermentation. The presence of trub decreases ester production, but increases fusel oil (higher alcohols) production by yeast. Trub can contribute negative flavor character to beer, darken the color of beer, decrease foam stability and contribute polyphenols that can combine with other compounds to create staling. Trub can also interfere with or suffocate yeast activity when yeast is harvested for reuse, causing slower fermentation.

Interestingly, it was found by researchers at Coors Brewing Company that oxygen had the same positive effect on fermentation rate as trub. When filtered trubless wort was fermented with a normal amount of oxygen, it took 30 percent longer to complete fermentation than the wort with trub and normal amounts of oxygen. Furthermore, it was found that filtered trubless wort with high oxygen fermented equally as well as trubed wort with low oxygen. From these and other observations the researchers partially concluded that the fatty acids (lipids in particular) in the trub provided the same type of nutrient energy as the oxygen effectively did in the filtered wort.

So what’s a homebrewer to do? On one hand trub seems to enhance fermentation, which is just what we want, but it also seems to negatively impact the flavor of the beer. Relax. Don’t worry. Have a homebrew. Trub’s influence is a relatively minor consideration. Keep in mind that there are many other steps in the homebrewing process that can enhance or inhibit the same effects—to a much greater degree. Keep things in perspective, and when you have the other process variables under control, consider trub and its removal more seriously. Don’t worry about it, yet know you can continue to improve and fine-tune the quality of your homebrew.

The consensus in brewing literature encourages the removal of trub. With a homebrewer’s needs and considerations kept in perspective, one would be doing very well to remove 60 to 80 percent of the trub. This can be achieved with some fairly simple techniques.

TRUB: HOW TO REMOVE IT

There are three principal methods that the homebrewer can employ to remove trub: settling, filtration and whirlpooling.

Settling of the trub will occur if the wort, hot or cool, is allowed to sit quietly. The settling can be observed in a quiet brewpot or in a 5-gallon (19-l.) glass fermenter of cooled wort. Transfer the top clear layer of wort to another container to separate it from the trub. Maintain sanitary conditions when dealing with cooled wort.

A major problem with transferring clear cooled wort by siphoning or other means is that there is quite a bit of wasted wort, as much as 10 to 15 percent, because even though the trub has settled to the bottom, it is still suspended in fermentable wort. There are other alternatives, so please read on.

Filtration offers a very good means for removing most of the hot break if whole hops are used in the brew kettle. When used as a filter bed through which all of the hot wort must pass, the hops offer a natural means to catch much of the trub. When employing whole hops as a filtration bed in this manner, they mustn’t be disturbed once the flow of wort through them has commenced. A simple strainer doesn’t offer a very effective means to collect the hops and utilize them as a filter. The ambitious homebrewer will need to fashion a hop-back. A lauter-tun can serve as a hop-back, but care must be taken to minimize aeration of the hot wort during transfer and to maintain sanitation during the entire process as the wort flows from the hop-back to the fermenters. As an assurance of sanitation, one could bring the filtered wort back to a boil before transferring it to the fermenter.

If you are using hop pellets, this method won’t work, but the next one will.

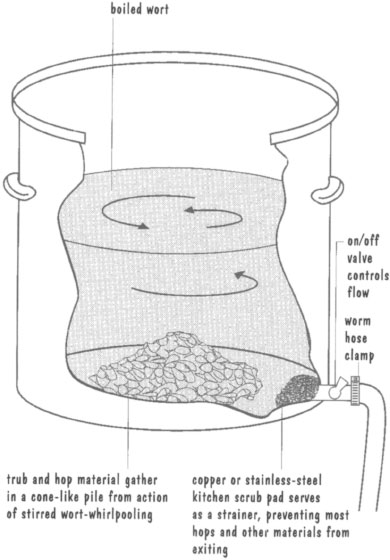

Whirlpooling sets the hot wort into a circular whirlpool motion in a container. The heavier hop and trub particles will migrate to the center of the container because of the forces involved. Take a cup of tea with tea leaves in it and stir the cup in a swirling motion. Observe the tea leaves as they migrate to the center and into a conelike pile. This is exactly what happens to trub and hops in a whirlpool effect.

Commercial brewers and homebrewers with more sophisticated equipment will apply this principle to their brewpot or another tank and remove the wort from the side of the tank through an outlet.

TRUB, WHIRLPOOLS AND EQUIPMENT

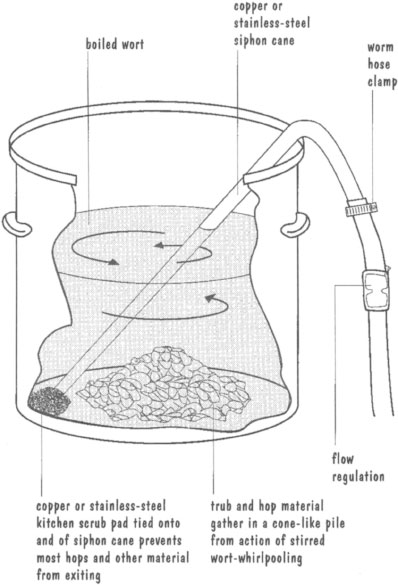

With a little ingenuity, homebrewers can use all three principles—settling, filtration and whirlpooling—to their advantage with no more than a minimal amount of simply fashioned equipment. You will need a 3-foot (about l-m.) length of copper or stainless steel tubing. Bend one end so that it forms a cane shape. Tie on a coppermesh cleaning pad to the straight end of the tube with some string or twine. This will serve as a partial filter and prevent clogging of the siphon tube-hose you are fabricating. Attach a 4-foot length of siphon hose to the crooked cane end of the tube. Your siphon equipment is ready.

Stir your boiled wort in a vigorous circular motion, taking care to minimize aeration. This will take about 5 to 10 seconds. Replace the lid on the pot and let it sit for 5 to 10 minutes. The wort will partially clear and the hop and trub particles will tend to accumulate in a cone at the center and bottom of the pot. Fill your siphon hose completely with tap water and, while holding your thumb over the end of the hose, carefully place the copper-padded end of the tube in the bottom and side of the brewpot. Let ’er rip. Start the flow of the hot wort into an awaiting other brewpot or two. Be careful to minimize aeration.

As the level of the wort approaches the bottom of the pot, you will be quite impressed at the entanglement of hops and gooey trub. Tilt the pot once the level gets close to the bottom in order to get as much good wort out as possible. Sparging with water is not recommended unless the water is acidic. Alkaline water will dissolve the precipitated trub and you will reverse all of what you’ve just accomplished.

Note: This siphon isn’t necessary if your brewpot has an outflow on the side bottom where you can attach a hose. The copper pad can still be placed at the exit hole inside the pot.

At this point, while marveling at all that stuff you just filtered out, you may bring the wort back to a boil for a very short time to sanitize it. Then proceed with chilling the wort and transferring it to the fermenter.

During the chilling process precipitation of additional tannin-protein trub occurs. The precipitate is called the cold break. The more quickly the wort is chilled, the greater the amount of cold break that will be formed. It will be about 10 to 30 percent of the hot break. The principles of settling and whirlpooling are utilized by commercial brewers to remove the trub. However, most homebrewing methods do not offer the sanitary conditions required for additional handling of the wort during cold trub removal. Cold break accounts for about 15 to 30 percent of all the trub material precipitated during the boiling and chilling processes. If efforts have been made to remove most of the hot break trub, then you can relax and have a homebrew knowing that you’ve eliminated most of the trub. For homebrewers, the risk of contamination may not be worth the relatively minimal benefits gained by cold break removal.

If you are brewing those perfectly finessed German, Czech or American light lagers and Pilseners, you should consider maximizing the effects of trub removal. You will note improved clarity, less chill haze, better head stability and a finer grin on your face. If you’ve found a way to remove most of the trub, be sure to oxygenate exceptionally well. And if perchance you notice an onionlike character in your beer, you may have removed too much trub. Some brewers claim that total trub removal results in an onionlike character in the beer. If you are concerned, be on the safe side and leave a bit in for good measure.