Did you like it? You’ve planned for, brewed, fermented, packaged, waited for your beer to be ready. A chilled bottle is uncapped and poured into your favorite glass. Of course, your favorite glass is always the one that has your beer in it—always. Isn’t it? It’s a matter of personal preference whether you’ve poured the beer down the side of the glass or straight down the middle, but practically speaking, you’ve probably started out by pouring it down the side and watching how lively the beer becomes as the barley and hop nectar begins to express itself. If the beer needs more head, you’ll likely begin to pour it down the middle, creating the amount of foamy topping that suits your preference. So far you’ve given it your best shot.

You look at it, there in the glass. You smell it and then taste it. Is it any good? Well, the answer to that is quite simple. If you like it, then it is good, and nobody should ever convince you otherwise. The simple pleasures of enjoying great beer must never be forgotten.

Simple pleasure is quite enough reason to make and appreciate your own beer. However, an understanding of the basic principles of beer evaluation can offer any brewer an enhanced appreciation for beer character and can help improve or maintain quality.

BEER CHARACTER: THE DYNAMICS OF CHANGE

Beer Is A Food

From the moment we first brew our beer to when it is consumed, beer undergoes continual change. Flavors, aromas, sights and sensations are layered on one another. What one perceives is the net effect. There are hundreds of different compounds that contribute to the quality of beer. Some are not perceived at all, while others may be highlighted, but what is primarily being perceived is characters that are enhanced or suppressed by the interaction of the combination of everything beer is.

As beer ages, its character will change. Certain characters will be perceived to a greater or lesser degree, or perhaps not at all. Because of the layering of so many stimulating compounds in beer, it is quite possible that the perceived development of a specific character might be something new created in the beer during the aging process or something that has been there all along, but has been suppressed by the dominance of other characters. For example, the bitterness of a beer might be perceived to increase over a period of time, not because bitter compounds are increased, but rather because malty sweetness and body are being reduced, giving a perception of increased bitterness.

Other characters that are perceived may not each exist as a single character, but may be a synergistic combination of two or more factors that creates a unique perception all its own. This synergy may also have the effect of increasing the intensity of each factor involved.

Beer changes. What we perceive in those changes is not always a clear indication of what’s really happening, though often it is.

Buns and Alligators: How fresh is fresh and how long

will beer last?

Ponce de Leon searched for the fountain of youth, but only found himself up to his buns in alligators. Moral of the story: There is no simple answer to the question of age.

Commercially made beer is said to be brewery fresh just after it has been packaged and leaves the brewery. For most beer styles and at this time, the beer generally will be perceived as being at its best by most consumers. Some special styles of commercially made beer will be perceived as being enhanced in character with some age, but these styles are generally very strong beers with live yeast still in the bottle.

Homebrewed bottle-conditioned beer is quite another matter, but first let’s examine what is happening with commercially made beer. The most significant flavor changes that will come about in sterile-filtered or pasteurized commercial beer are usually the result of time and oxidizing reactions. This is assuming that the beer is not contaminated with significant amounts of beer spoilage microorganisms. There are countless other reactions that can also affect flavor, but the biggies are caused by oxidation—the reaction of oxygen with flavor compounds. This reaction is encouraged by heat, light and agitation. The character of old commercial beer is often described as tasting like wet cardboard, wet paper or rotten pineapple, or as winy, sherrylike, skunky and other not-so-wonderful adjectives.

Even if oxidation is minimal, there can be other flavor changes that are not considered true to the intent of the brewer and thus “not fresh-tasting.”

Now then, bottle-conditioned beer is still alive in the true sense of the word. If you’ve brewed cleanly, then what you have is a well-brewed beer with yeast still living in the bottle. That yeast can produce both desirable and undesirable characters. Obviously desirable is the carbon dioxide that adds effervescence. The presence of yeast can reduce some of the dissolved oxygen in the beer, helping minimize future oxidation reactions. Yeast can also reduce the diacetyl (buttery or butterscotch) character of a beer with age (though it cannot adequately reduce bacterially produced diacetyl). When yeast undergoes refermentation in the bottle, it will produce a small amount of undesirable byproducts. Normally many of these byproducts are released to the air in primary, secondary and lagering fermentation, but when sealed in a bottle, these undesirables are captured and must be aged out with some time. Bottle-conditioned beer may improve with some aging. As it reaches its peak flavor, one might consider homebrew to be “fresh” and as it was intended to be.

Now then, about that harshly bitter brew that seemed to get better with age. If you hadn’t put so many hops in to begin with, you wouldn’t have had to age it so long to mellow it out. Yes, the perception of bitterness is often diminished with age in a very hoppy beer. The beer’s bitterness will be perceived as becoming more balanced, but in the meantime, other age reactions occur, detracting from the balance. The skill to acquire is getting your bitterness proportioned correctly to begin with, so you can drink the beer sooner.

How long will homebrew maintain its fresh and intended character? It has so very much to do with how contaminant-free the beer is, as well as what temperature it is stored at and the type of beer it is. For beers in a range of 3 to 5½ percent alcohol, one can reasonably expect a fresh flavor to remain stable for one to three months if the beer is kept at temperatures below 60 degrees F (15.5 C). After three months, the beers will change, but if there is no bacterial or wild yeast activity, homebrew will keep for a year or two (sometimes more). However, oxidation and air ingress will eventually take their toll and the beer’s character may become no better than that of an old and tired commercially brewed beer.

One final thought on this subject before I open one of my seven-year-old barley wine ales: If your beer tastes good, it can never be beyond its time.

Before we can begin to discuss beer character in any detail, a language must be developed. Over many years many of the following descriptor definitions and possible sources have been developed and utilized by the American Homebrewers Association for homebrew competitions and educational purposes. They represent the most common attributes related to the character of homebrewed beers.

Desirable or undesirable? Can you recognize 17 different flavors or aromas often present in beer?

Acetaldehyde—Green applelike aroma; byproduct of fermentation. Can be perceived as breadlike or solventlike at high concentrations. Can be caused by low yeast levels and influenced by yeast strain.

Alcoholic—The general effect of ethanol and higher alcohols. Feels warming. Tastes sweetish.

Astringent—Drying, puckering (like chewing on a grape skin); feeling often associated with sourness. Tannin. Most often derived from boiling of grains, long mashes, oversparging or sparging with excessively hot or alkaline water. Metal ions in water or excessive trub in fermentation can contribute.

Bitter—Basic taste associated with hops; braunhefe or malt husks. Sensation is experienced on back of tongue.

Body—The mouth feel sensation of beer. Full or heavy body is more creamlike in consistency, while light-bodied or dry beer is thinner.

Cheesy—Old, stale, rancid hops and sometimes (in rare cases) old malt can cause this character.

Chill Haze—Haze caused by precipitation of protein-tannin compounds at cold temperatures. Does not affect flavor. Reduction of proteins or tannins in brewing or fermenting will reduce haze.

Chlorophenolic—Caused by chemical combination of chlorine and organics. Detectable at one to three parts per billion. Aroma is unique but similar to plasticlike phenolic. Avoid using chlorinated water.

Clean—Lacking off-flavors.

Cooked Vegetable/Cabbagelike—Aroma and flavor often due to long lag times and wort-spoilage bacteria that later are killed by alcohol produced in fermentation. The character persists as a byproduct.

Diacetyl—Described as buttery, butterscotch. Sometimes caused by abbreviated fermentation or bacteria.

DMS (dimethyl sulfide)—A sweet-cornlike aroma/flavor. Can be attributed to malt, short or nonvigorous boiling of wort, slow wort chilling or, in extreme cases, bacterial infection.

Estery-Fruity—Similar to banana, raspberry, pear, apple or strawberry flavor; may include other fruity-estery flavors. Often accentuated with higher-temperature fermentations, stirred or agitated fermentation, high pitching rates, fermentation of higher gravity beer, excessive wort aeration and certain yeast strains.

Fatty-Soapy—A lardlike, fatty or soapy character contributed by the autolyzation of yeast. Dormant yeast cells explode their fatty acids and lipids into the beer.

Fusel—Refers to higher alcohols and some esters. Sometimes referred to as fusel oils because of their oily nature as a compound (see Solventlike). Also can be roselike and floral. High levels of amino acid protein in wort, high temperatures, high-gravity wort, agitated wort during fermentation, great yeast growth, all can contribute to higher levels of fusels.

Grainy—Raw grain flavor. Cereal-like. Some amounts are appropriate for some beer styles. Beers with high pH tend to have grainier flavors.

Hoppy—Characteristic odor or the essential oil of hops. Does not include hop bitterness.

Husky—see Astringent.

Light-struck—Having the characteristic smell of a skunk, caused by exposure to light whose wavelength is blue-green at 520 nanometers. Some hops can have a very similar character.

Metallic—Possibly caused by exposure to metal or by fatty acid reactions. Also described as tinny, coins, bloodlike. Check your brewpot and caps.

Moldy-Musty—Character may be contributed by water source containing algae, or by moldy hoses or plumbing. Common with corked beer.

Nutty—As in Brazil nut, hazelnut or fresh walnut; sherrylike.

Oxidized-Stale—Develops in the presence of oxygen as beer ages or is exposed to high temperatures; wet cardboard, papery, rotten vegetable or pineapple, winy, sherry, uric acid. Often coupled with an increase in sour, harsh or bitter flavors. The more aeration in bottling, filtering and transferring or the more air in the headspace, the more quickly a beer oxidizes. Warm temperatures dramatically accelerate oxidation.

Phenolic—Can be any one or a combination of a medicinal, plastic, electrical fire, Listerine-like, Band-Aid-like, smoky or clovelike aroma or flavor. Most often caused by wild strains of yeast or bacteria. Can be extracted from grains (see Astringent). Sanitizing residues left in equipment can contribute.

Salty—Flavor associated with table salt. Sensation experienced on sides of tongue. Can be caused by presence of too much sodium chloride, calcium chloride, or magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts).

Soapy—See Fatty.

Solventlike—Flavor and aromatic character of certain alcohols, often caused by high fermentation temperatures. Like acetone, lacquer thinner.

Sour-Acidic—Pungent aroma, sharpness of taste. Basic taste is like vinegar or lemon; tart. Typically associated with lactic or acetic acid. Can be the result of bacterial infection through contamination or the use of citric acid. Sensation experienced on sides of tongue. Acetic acid (vinegar) is usually only a problem with wooden fermenters and introduction of oxygen.

Sweet—Basic taste associated with sugar. Sensation experienced on front tip of tongue.

Sulfurlike (H2S; Hydrogen Sulfide)—Rotten eggs, burning matches, flatulence. A byproduct with certain strains of yeast. Fermentation temperature can be a big factor. Diminishes with age. Can be more evident with bottle-conditioned beer.

Worty—The bittersweet character of unfermented wort. Incomplete fermentation.

Yeasty—Yeastlike flavor. Often due to strains of yeast in suspension or beer sitting on sediment too long.

Accurately evaluating beer does not come easy. It takes dedication, training, years of practice and a very wide variety of beer experiences. As homebrewers, you have an advantage—you know the process and understand where flavors can originate once you learn how to identify them.

If you want to learn how to evaluate beer, you have your wort cut out for you. There are more than 850 chemical compounds that occur naturally in the fermentation process. Many hundreds of these compounds remain in the beer or change to something else with time and condition. These compounds titillate the tens of thousands of taste buds in our mouths. The resulting symphony is the taste we nonchalantly identify as beer.

We find ourselves attempting to isolate and identify one or a few flavors among hundreds. How our brains manage to do this is a wonder still not fully understood. With desire we can train ourselves: first, how to recognize a type of character; and second, how to perceive various intensities or particular characters. The final test, and the most difficult, is to recognize, perceive and isolate a number of characters among many in our glass of beloved beer.

Let’s consider the reasons why brewers would want to know how to evaluate beer.

Quality Control and Consistency. Every large brewery in North America has a regular program for evaluating its beer for the sole purpose of ascertaining that its quality is consistent from batch to batch. The breweries are not necessarily trying to detect unusual flavors in order to identify their origins. Instead, beer evaluators usually are specially trained to evaluate just one style of beer—the brewery’s own brand.

To Be Able to Describe a Given Beer. How does your beer taste? “This beer tastes good (or bad).” “It’s a party beer.” “It’s less filling.” “The one beer to have when you want more than one.” These generic descriptions just don’t cut it anymore if you want to identify for yourself or communicate to other beer enthusiasts your beer’s character.

Because of the proliferation of beer styles being brewed in North America, a language has developed over the last decade that effectively communicates the characteristics of beer. If you can evaluate your beer’s strong or weak points and describe them accurately, you may be able to improve the character of your beer and make exactly what you want.

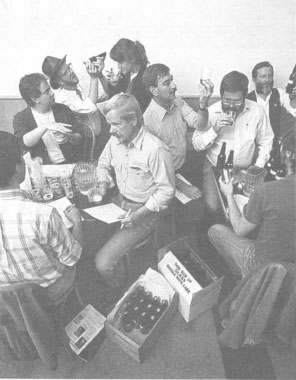

To Score And/Or Judge in a Competition. Beer competitions are becoming more and more popular. Hundreds of beer enthusiasts and brewers are spending a great deal of time learning to evaluate beer and determine a winner in a contest. This is a specialized perspective on the art and science of evaluation, and one that has taken the direction of blending objectivity with subjectivity. The evaluators or judges use scientific and technical terms in objectively assessing beer qualities, and their subjective senses to assess the beer’s drinkability and appropriateness to a style.

To Define Styles. For every beer you brew, there is born a style. The skill of the brewer, combined with the tools at his or her disposal, makes for the individuality of any glass of beer. So why do definitions of styles emerge when we take pride in our own uniqueness? One reason is to develop traditions, enthusiasm and reasons to argue about better or worse, too malty or bitter; to create identity.

To Detect Problems and Improve Your Own or Someone Else’s Beer. This is perhaps the most challenging of all the reasons to evaluate beer. Not only do you need to identify any one of hundreds of characters, but you also need to identify the source of the character. If you are able to evaluate a beer’s flavor, aroma, appearance, mouth feel and aftertaste—and then identify the source of these characters—you can control, adjust and improve the quality of your brew.

Sophisticated equipment can be used to measure, right down to the last little molecule, the kinds and amounts of constituents that could be in your beer. Technological evaluation may augment the objective and subjective findings of a trained evaluator, but it can never replace them.

The human senses of taste, smell, sight, hearing and touch can be trained as very effective tools to evaluate beer. But it takes patience and development of confidence, time and, above all, humility. It takes practice. I know. I have watched hundreds of beer enthusiasts and brewers improve their evaluation skills over the years, to such a degree that they enjoy beer more and brew better beer.

Sight. You can tell a lot about a beer by just looking at it while it’s in the bottle or glass. Excessive headspace in the bottle is an indication that air content may be high. This tells you that oxidized flavor and aroma characters may follow. A surface deposit ringing the inside of the bottle’s neck is a clear indication of bacterial or wild yeast contamination. In this case, sourness and excessive acidity may result. Gushing (another visual experience) also may be the result of bacterial or wild yeast contamination.

American Homebrewers Association Sanctioned Competition Program

BEER SCORE SHEET

BOTTLE INSPECTION Comments ____________________

____________________

BOUQUET/AROMA (as appropriate for style) 10 _____

Malt (3), Hops (3), Other Aromatic Characteristics (4)

Comments ____________________

____________________

APPEARANCE (as appropriate for style) 6 _____

Color (2), Clarity (2), Head Retention (2)

Comments ____________________

____________________

FLAVOR (as appropriate for style) 19 __________

Malt (3), Hops (3), Conditioning (2), Aftertaste (3), Balance (4), Other Flavor Characteristics (4)

Comments ____________________

____________________

BODY (full or thin as appropriate for style) 5 __________

Comments ____________________

____________________

DRINKABILITY & OVERALL IMPRESSION 10 _____

Comments ____________________

____________________

Scoring Guide

Excellent (40–50): Exceptionally exemplifies style, requires little or no attention

Very Good (30–39): Exemplifies style well, requires some attention

Good (25–29): Exemplifies style satisfactorily, but requires attention

Drinkable (20–24): Does not exemplify style, requires attention

Problem (<20): Problematic, requires much attention

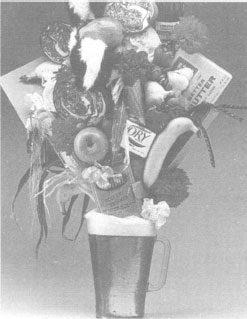

It’s a rough job, but someone’s got to do it. Judging and evaluating beer is serious business, demanding time, patience, training, practice and humility. But keep in mind, beer judges don’t spit it out.

Sediment in a filtered, yeast-free beer may indicate an old, stale beer. Watch out for gushing. Sediment also may indicate precipitation of oxalates, a result of the brewing water lacking appropriate brewing salts—a sure cause of gushing.

Hazy beer can be the result of bacterial or yeast infection. Chill haze, a precipitate of a tannin-protein compound, doesn’t affect the flavor, but it can be remedied when identified.

When poured into a brandy snifter, high-alcohol beers such as doppelbocks and barley wines verify their strength by showing their legs on the sides of the glass. Legs refers to a coating of liquid that concentrates into streams as it runs down the side of a glass.

The complete lack of foam stability in a glass of newly poured beer (assuming the glass is beer-clean) is an indication that the beer may be stale, old and oxidized.

Hearing. It takes a lot of attention, but for an experienced evaluator, that sound upon opening—of gas escaping from a bottle—is music with specific tones for different volumes of carbon dioxide.

Smell. The most sensitive and the most telling of our senses is our sense of smell. Assessing a beer’s aroma should be a quick experience. Our smell detectors quickly become anesthetized to whatever we are smelling. For example, you may walk into a room and smell the strong aroma of coffee perking. Five minutes later, the smell lingers just as strongly, but you don’t notice it any longer.

Our smell detectors reside in a side pocket of dead air along our nasal passage. In order to assess aromas, we must take air into this side pocket. The most effective way of doing this is to create a lot of turbulence in the nasal passage. Several short, strong sniffs or long, deep sniffs help get the aromatic molecules of vaporized beer smells into this pocket. Then our memory and current experience combine to identify what we smell.

Getting the aromas out of the beer doesn’t happen so easily. It is best done with beers warmed to at least 45 to 50 degrees F (7 to 10 degrees C) so that volatiles and aromatic compounds will change form from liquid to gas. Swirl a half-full glass of beer to release the carbon dioxide bubbles into the air, carrying with them other aromatic gases.

Note that some constituents of beer flavor and aroma are so volatile that they virtually disappear from beer within a matter of a few minutes. This is the case with some sulfur-based compounds like DMS (a sweet-cornlike aroma), giving the beer an entirely different smell and taste after it has sat out for a time.

Taste. The tongue is the main flavor assessor in the mouth. It is mapped out in four distinct areas. Bitterness is experienced at the back of the tongue, sweetness at the front tip of the tongue, and saltiness and sourness on the sides of the tongue. It is interesting to note that 15 to 20 percent of Americans confuse sour with bitter and vice versa. Clarify this for yourself by noting where on the tongue you are experiencing the taste sensation.

“Chew” the beer when evaluating. Because different areas of the tongue experience various flavors, you must coat all of your tongue and mouth with the beer and then swallow. Beer evaluators—don’t spit it out! It is important to assess the experience of swallowing beer for its aftertaste and so that all parts of the mouth are exposed. There are flavor receptors on the sides, back and roof of the mouth independent of the tongue.

Touch and Feel. Your mouth, most of all, senses the texture of the beer. Often called body, the texture of beer can be full-bodied or light-bodied as extremes. Astringency (also related to huskiness and graininess) can also be assessed by mouth feel. It is not a flavor, but rather a dry, puckery feeling, exactly like chewing on the skin of a grape. This astringent sensation most often comes from tannins excessively extracted from grains as a result of oversparging, sparging with overheated water or having a high pH. Sometimes astringency can be the result of milling your grains too finely.

Other sensations that can be felt are oily, cooling—as in menthol-like—burning and hot or cold.

Pleasure. This is our sixth sense. This is the close-your-eyes drinkability, the overall impression, the memorableness of the beer. No evaluation is complete without this final assessment. Is the beer pleasurable? Would you want another? This is the assessment and the evaluation that turned you into a homebrewer, isn’t it?

Our senses, like a $100,000 machine plugged into the electric socket, are sensitive to power surges, brownouts and other ups and downs that influence the “show.” Our own genetic makeup can affect our ability to detect certain chemical compounds’ aromas and flavors. Also, our health is a very significant factor. Two to three days before we show the first outward symptoms of a cold or flu, our taste buds may go completely haywire. Taste panels that make million-dollar decisions consider this and do not rely on just one taster but on several in order to account for temporary inaccuracies of perception.

Finally, the environment in which we assess should be comforting and not distracting. Smoke, loud music and unusual lighting should be avoided.

SOME FACTORS INFLUENCING THE CHARACTER OF BEER

Here is a thumbnail sketch of some of the more common factors influencing the character of beer.

Malt—influences color, mouth feel, sweetness, level of astringency, alcohol strength.

Hops—influences bitterness level, flavor, aroma (can be citrusy or floral), and sometimes can contribute to a metallic character.

Yeast—strains and environment can affect diacetyl (buttery-butterscotch) levels; hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg smell), particularly in bottle-conditioned beer; phenolic character, including clove; plasticlike aroma and flavor; fruitiness and esters. Release of fatty acids from within cell walls can contribute to soapy or lardlike flavor.

Water—chlorinated water can result in harsh chlorophenolic (plasticlike) aroma and flavor. Saltiness results from excess of certain mineral salts. High pH can result in harsh bitterness from unwanted extraction of tannin from grain and/or hops. Algae in water source can contribute moldiness or mustiness.

Milling—grain too finely crushed can result in husky-grainy and/or astringent character.

Mashing—temperature can affect level of sweetness, alcohol, body or mouth feel, astringency.

Temperature—during fermentation it can affect level of estery-fruitiness and level of fusel and higher alcohols; slow chilling of wort can increase DMS (sweet-cornlike character) levels.

Lautering—temperature and alkalinity of sparge water can affect level of tannins and subsequent phenols detected in finished beer.

Boiling—short boiling times or nonvigorous boils can result in high DMS levels; vigorous boiling precipitates proteins out of solution. Also extracts hop flavors.

Fermentation—High temperatures can cause fusel alcohols and/or solventlike characters; cooling regime can elevate or decrease diacetyl levels in finished beer.

Sanitation—lack of sanitation can result in bacterial or wild yeast contamination, causing unusual effects on flavor, aroma, appearance, texture; residues of sanitizer can contribute to medicinal-phenolic character.

Design—design of equipment—kettles, fermenters and plumbing—can grossly affect boiling regime, fermentation cycles, cleanability; the same combination of ingredients can be affected by different configurations and sizes of equipment.

Scaling batch size up or down can have significant and unforeseen effects on character of beer.

Temperature—warm temperatures grossly affect the freshness of beer; warm temperatures speed up the oxidation process.

Oxygen—more than anything else, oxygen destroys the flavor of finished beer; oxygen combines with beer compounds and alcohol to produce negative flavors and aromas described as winy, stale, sherrylike, papery wet cardboard, rotten vegetables, rotten pineapple.

Light—blue-green wavelengths at 520 nanometers photochemically react with hop compounds to produce a light-struck skunky character. Green and clear class offer no protection.

Agitation—rough handling enhances the oxidation process.

Becoming a knowledgeable beer drinker takes practice. It begins with tasting and observing your beer from its inception. Taste, smell, feel and look at your ingredients. Watch your brewing process. Taste the liquids that are being transformed into beer as you progress. Taste the wort, taste the various rackings of fermented beer. Note appearances; note how vigorous the fermentation is and how quickly it clears. Taste the beer as you bottle it, then taste it after one week, two weeks, three weeks and a month. Accompany the beer along its way with your senses. Knowing and feeling the soul of your beer takes time and practice. Don’t expect an “aha” phenomenon to occur with every batch. Your knowledge and understanding are cumulative. Use your senses more than anything else. These perceptions are your foundation for further training and development of beer awareness.

With cumulative experience and knowledge you will begin to be able to predict the outcome of your beer and how it will change before it is ready to drink. As the beer matures, you’ll recognize what kind of sulfur characters come and go with age. You’ll know that some phenolic characters are likely to get worse with age, and some can diminish. You’ll observe the rise and fall of bitterness, diacetyl. Some esters will increase with age, and others will be perceived to diminish. You’ll be able to gauge the potential of your beer. Homebrewing is different from commercial brewing. Many commercial brewing principles and theories can be appropriately applied to homebrewing, but there are exceptions. If you brew enough and use your senses, you will discover the delightful uniquenesses of homebrew.

Limber up that elbow. Taste beer. Yours, others’—commercial and homebrewed.

Serve samples at a temperature no cooler than 50 degrees F (10 C), preferably 50 to 60 degrees F (10–15.6 C) for ales. Serve in an environment that is comfortable, well lit, odor-free and quiet, for maximizing your sense of perception.

Training Aids. Here is a table of substances you can add to 12 ounces (355 ml.) of light-flavored beer in order to help you learn how to identify particular aroma or flavor characters.

Some of these samples are difficult to make and depend on their strength because many of these aromas are very volatile and unstable. Make these doctored beer samples only 12 to 24 hours before they are actually sampled. Otherwise, many of them are so volatile and unstable that their propensities will diminish.

You may find some of the samples will be too strong, and some much too weak, as far as your senses are concerned. Individual perception thresholds are different.

Some of the chemicals are intensely pungent in their concentrated form and will require a well-ventilated mixing area. A vented hood with strong fans is mandatory for chemicals such as diacetyl, ethyl acetate and acetaldehyde. Use safety glasses to protect your eyes if handling concentrated lactic acid.

Note that lactic acid does not have an aroma in and of itself. Other byproducts produced by bacteria produce aromatics in beer.

A Homebrewers Guide to Better Beer

This chart is intended for use by brewers as a guide in helping to identify the causes of certain more commonly occurring beer flavors. It is not intended to represent a complete compilation of beer flavors or their origins. Published by the American Homebrewers Association.

Profile Descriptor: Alcohol (ethanol)—a warming prickly sensation in the mouth and throat.

Ingredients: High: increase fermentable sugars through use of malt or adjuncts.

NOTE: use of corn, rice, sugar, honey adds alcohol without adding body.

High: healthy and attenuative yeast strains.

Process: High: within the general 145 to 158 degree F range of mashing temperatures the lower mash temperature produce more fermentables, thus more resulting alcohol.

High: aeration of wort before pitching aids yeast activity.

High: fusel (solvent-like) alcohols are produced at high temperatures.

Handling and Processing: Age and oxidation will convert some of the ethanol to higher solvent-like alcohols.

Profile Descriptor: Astringent—(see Husky/Grainy)

Bitter—a sensation generally perceived on the back of the tongue, and sometimes roof of the mouth, as with caffeine or hop resin.

Ingredients: High: black and roasted malts and grains.

High: great amounts of boiling hops.

High: alkaline water can draw out bitter components from grains.

Process: High: effective boiling of hops.

Low: high fermentation temperatures and quick fermentation rates will decrease hop bitterness.

Equipment: Low: filtration can remove some bitterness.

Profile Descriptor: Body—not a flavor but a sensation of viscosity in the mouth as with thick (full-bodied) beers or thin (light-bodied) beers.

Ingredients: Full: use of malto-dextrin, dextrinous malts, lactose, crystal malt, caramel malt, dextrine (Cara-Pils) malt.

Thin: use of highly fermentable malt.

Thin: use of enzymes that break down carbohydrates in mash, fermentation of storage.

Process: Full: high-temperature mash.

Low: low-temperature mash.

Handling and Processing: Low: age will reduce body.

Low: wild yeast and bacteria may reduce body by breaking down carbohydrates.

Profile Descriptor: Clarity—visual perception of the beer in the bottle and alter it is poured.

Ingredients: High: use of protein reducing enzymes (papain).

Low: chill haze more likely in all malt beers because higher protein than malt and adjunct beers.

Low: wheat malt and unmalted barley cause more chill haze than malted barley and corn and rice adjuncts.

Low: poor flocculant wild yeast may cause poor sedimentation.

Low: bacteria causes cloudiness and haze.

High: use of polyclar or activated silica gel.

Process: Low: overmilling/grinding grain.

High: long, vigorous boil and proper cooling.

Equipment: Low: bacteria from dirty plastic equipment, especially siphon and blow-out hoses, scratched fermenter.

High: filtration can help clear

Handling and Processing: Low: unclean bottles can cause bacterial haze.

Profile Descriptor: Color-visual perception of beer color.

Ingredients: Dark: dark malts (crystal, Munich, chocolate, roasted barley, black patent).

Light: exclusive use of lighter malts and starch adjuncts.

Process: Dark: scorching.

Dark: caramelization with long boil.

Equipment: Low: filtration can reduce color.

Profile Descriptor: Degree of Carbonation

Ingredients: High: bacteria and wild yeast may break down carbohydrates not normally fermentable and create overcarbonation and gushing.

High: over priming.

NOTE ON GUSHING: excessive iron content causes gushing; malts containing Fusarium (mold) from wet harvesting of barley causes gushing; precipitates of excess salts in bottle cause gushing.

Process: Low: cold temperatures inhibit ale yeast.

Low: long lagered beer may not have enough viable yeast for bottle conditioning (carbonating) properly.

Equipment: High: unsanitary equipment can introduce bacteria which can cause overcarbonation and gushing.

Handling and Processing: High: unclean bottles can cause bacterial growth and gushing.

High: overpriming kegs; prime kegs at one-third normal rate.

High: agitation.

Low: improper seal on bottle cap.

Profile Descriptor: Diacetyl—butter or butterscotch flavor.

Ingredients: High: unhealthy, non-flocculating yeast.

High: not enough soluble nitrogen-based yeast nutrient in wort.

High: not enough oxygen in wort when pitching yeast.

High: bacterial contamination.

High/Low: yeast strain will influence production of diacetyl.

High: excessive use of adjuncts such as corn or rice, deficient in amino acid (soluble nitrogen based nutrients).

Process: High: chilling fermentation too soon.

High: high-temperature initial fermentation.

High: premature fining takes yeast out of suspension too soon.

Low: agitated extended fermentation.

Low: high temperature during extended fermentation.

Low: kraeusening.

Equipment: High: bacteria from equipment.

High/Low: configuration and size of fermenting vessel will influence production.

Profile Descriptor: Dimethylsulfide (DMS)—cooked cabbage or sweet corn-like.

Ingredients: High: high-moisture malt, especially 6-row varieties.

High: bacterial contamination of wort.

Low: use of 2-row English malt.

High: under pitching of yeast (lag time)

High: bacterially infected yeast slurry.

Process: Low: longer boil will diminish DMS.

High: oversparging at low temperatures (especially lower than 160 degrees F).

Equipment: High: bacteria from equipment.

Handling and Processing: High: introduction of unfiltered CO2 produced by fermentation. Bottle priming will produce small amounts.

Profile Descriptor: Fruity/Estery-flavors similar to fruits such as: strawberry, banana, raspberry, apple, pear.

Ingredients: Yeast strains produce various esters.

High: loaded with fruit.

Process: High: excessive trub.

High: warm fermentation.

High: high pitching rates.

High: high gravity wort.

High: high aeration of wort.

Low: opposite of above.

Handling and Processing: Low: age will reduce esters to closely related fusel alcohols and acids (solventlike qualities).

Profile Descriptor: Head Retention—physical and visual degree of foam stability.

Ingredients: Good: high malt content.

Poor: use of overmodified or underkilned malt.

Good: mashing in of barley flakes.

Good: licorice, crystal malt, dextrine (Cara-Pils) malt, wheat malt.

Good: high bittering hops in boil.

Poor: hard water.

Poor: germ oil in whole grain.

Poor: elevated volumes of higher alcohols.

Good: high nitrogen content.

Process: Low: oversparging (releases fatty acids)

Low: high aeration of wort before pitching.

Low: extended enzymic molecular breakdown of carbohydrates in mashing.

Low: fatty acid release during yeast autolysis.

Low: high fermentation temperatures (production of higher alcohols).

High: good rolling boil in kettle.

Equipment: Poor: cleaning residues, improper rinsing of fats, oils, detergents, soaps.

Poor: filtration can reduce head retention.

Handling and Processing: Low: oxidation/aging breaks down head stabilizing agents.

Low: dirty bottles, improperly rinsed.

Low: improperly cleaned glasses.

Profile Descriptor: Husky/Grainy (Astringent bitter)—raw grainlike flavor, dry, puckerlike sensation as in grape tannin.

Ingredients: High: alkaline or high sulfate water.

High: stems and skins of fruit.

High: 6-row more than 2-row malt.

Process: High: oversparging grains.

High: boiling grains.

High: excess trub.

High: poor hot break (improper boiling).

High: overmilling/grinding.

High: high temperature (above 175 degrees F) sparge water.

Handling and Processing: Low: aging reduces astringency.

Profile Descriptor: Light struck (skunky)—like a skunk (the British describe this character as “catty” because there are no skunks in the U.K).

Ingredients: High: some varieties of hops.

Equipment: High: fermenting beer in glass carboy in bright light.

Handling and Processing: High: light striking beer through green or clear glass and over a prolonged time through brown glass. NOTE: effect is instantaneous with clear or green glass.

Profile Descriptor: Metallic—tinny, coin like, bloodlike.

Ingredients: High: iron content in water.

Equipment: High: mild steel, aluminum, cast iron.

High: cleaning stainless steel or copper without subsequently oxidizing surfaces to form a protective layer of oxide on metal.

Profile Descriptor: Oxidation—paper or cardboardlike, winey, sherrylike, rotten pineapple or rotten vegetables.

Ingredients: Low: addition of ascorbic acid (Vitamin C).

Process: High: aeration when siphoning or pumping.

High: adding tap or aerated water to finished beer.

Equipment: High: malfunction airlock.

Handling and Processing: High: too much air space in bottle.

High: warm temperatures.

High: age.

Profile Descriptor: Phenolic—medicinal. Band-Aid-like, smoky, clovelike, plasticlike.

Ingredients: High: chlorinated (tap) water.

High: wild yeast.

High: bacteria.

High: wheat malt (clovelike) or roasted barley/malts (smoky).

Process: High: oversparging of mash.

High: boiling grains.

Equipment: High: cleaning compound residue.

High: plastic hoses and gaskets.

High: bacterial and wild yeast contamination.

Handling and Processing: High: defective bottlecap linings.

Profile Descriptor: Salty—sensation generally perceived on the sides of the tongue as with table salt (sodium chloride).

Ingredients: High: brewing salts, Particularly those containing sodium chloride (table salt) and magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts).

Profile Descriptor: Sour/Acidic—sensation generally perceived on the sides of the tongue as with lemon juice (citric acid).

Ingredients: High: introduction of lactobacillus, acetobacter and other acid-forming bacteria.

High: too much refined sugar.

High: addition of citric acid.

High: excessive ascorbic acid (Vitamin C).

Process: High: mashing too long promotes bacterial growth and acid byproducts in mash.

High: bacteria in wort, fermentation.

High: excessive fermentation temperatures promote bacterial growth.

Low: sanitize all equipment.

Equipment: High: bacteria harbored in scratched surfaces of plastic, glass, stainless, improper welds, valves, spigots, gaskets, discolored plastic.

High: use of wooden spoon cooled wort or fermentation.

Handling and Processing: High: storage at warm temperatures.

High: unsanitary bottles or kegs.

Profile Descriptor: Sulfur—sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide (rotten eggs), see DMS, see light struck, yeastlike flavor.

Ingredients: High: various yeast strains will produce byproducts.

High: malt releases minor amounts.

Process: High: yeast autolysis: sedimented yeast in contact with beer in fermenter too long.

High/Low: yeast strains will influence.

Profile Descriptor: Sweet—sensation generally perceived on the tip of the tongue as with sucrose (white table sugar).

Ingredients: High: high malt content.

High: crystal malt. Munich malt and toasted malt create sweet malt flavor.

High: low hopping.

High: licorice.

High: low attenuation or unhealthy yeast strains.

Process: High: within the general 145 to 150 degree F range of mashing temperatures the higher mash temperatures produce more unfermentable carbohydrates.

Handling and Processing: Low: aging reduces sweetness.

Substances used to duplicate various beer characters (Much of this information is based on Dr. Morton Meilgaard’s work on the subject and my own and Greg Noonan’s experience with handling samples)

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0110

Descriptor: Alcoholic

Substance Used for Recognition: Ethanol

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 15 ml.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 40 ml.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0111

Descriptor: Clove/Spicy/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Eugenol

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 100 mcg.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 265 mcg.

Substance Used for Recognition: Allspice

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 2 g.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 5 g.

Substance Used for Recognition: Cloves

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: (marinate 2 or 3 cloves in beer)

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0112

Descriptor: Winy/Fusely

Substance Used for Recognition: Chablis wine

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 1 fl. oz.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 2.7 fl. oz.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0123

Descriptor: Solventlike/DO NOT DRINK Acetone

Substance Used for Recognition: Laquer thinner

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .03 ml.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .08 ml.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0133

Descriptor: Estery, Fruity, Solventlike/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Ethyl acetate

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .028 ml.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .076 ml.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0150

Descriptor: Green Apples/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Acetaldehyde

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .016 ml. or 16 mg.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .040 ml. or 40 mg.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0220

Descriptor: Sherry

Substance Used for Recognition: Sherry

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 1.25 fl. oz.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 3.25 fl. oz.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0224

Descriptor: Almond, Nutty/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Benzaldehyde Almond extract

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .002 ml. or 2 mg. 4 drops

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .005 ml. or 5 mg. 11 drops

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0503

Descriptor: Medicinal, Band-Aid-like, Plasticlike/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Phenol

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .003 ml. or 3 mg.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .010 ml. or 10 mg.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0620

Descriptor: Butter, Butterscotch/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Diacetyl Butter-flavor extract

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .00005 ml. 4 drops

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .00014 ml. 11 drops

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0710

Descriptor: Sulfury/Sulfitic/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Sodium or Potassium

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 20 mg.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 50 mg.

Descriptor: Sulfur dioxide/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Metabisulfite

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0721

Descriptor: Skunky, Light struck

Substance Used for Recognition: Beer exposed to sunlight for I hour

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0732

Descriptor: Sweet corn, DMS/DO NOT DRINK

Cabbage/DO NOT DRINK

Substance Used for Recognition: Dimethylsufide/DMS (note: unstable)

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .00003 ml. or 30 meg.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .0001 ml. or 100 meg.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0800

Descriptor: Stale, Cardboard, Oxidation

Substance Used for Recognition: Open bottle. Recap. Heat sample for one week at 90–100°F, or marinate cardboard in beer

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0910

Descriptor: Sour/Vinegar/Acetic (acid)

Substance Used for Recognition: White vinegar

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 7.5 ml.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 25 ml.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0920

Descriptor: Sour/Lactic (acidic) flavor only

Substance Used for Recognition: Lactic acid

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 0.4 ml. of 16% solution

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 1.1 ml. of 16% solution

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0100

Descriptor: Sweet flavor only

Substance Used for Recognition: Sucrose sugar

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 5.3 g.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 14 g.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0110

Descriptor: Salty flavor only

Substance Used for Recognition: Table salt (NaCl)

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: 1.2 g.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 3.2 g

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: 0120

Descriptor: Bitter flavor only

Substance Used for Recognition: Isohop extract

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: .0015 ml.

Concentration in One Quart Beer: .004 ml.

Meilgaard Term Ref. No.: —

Descriptor: Hop Aroma

Substance Used for Recognition: hop oil

Concentration in 12-oz. Beer: one drop

Concentration in One Quart Beer: 2 drops

NOTE: As indicated, some of these substances are toxic and should not be tasted.