Aboard the Sea Song

Anton had always enjoyed salooning, as his brother called it, but now that he had heard the sailors sing along with the accordion under the stars with the ship running fast beneath them, listening to the shanties in a crowded, smoky room was not the same. Still, it was better than nothing, so he slipped behind the customary loose wallboard and settled himself on his barrel behind the door. A glow warmed his chest as the patrons’ chatter subsided and a tall, young sailor stood up to lead the singing. Anton knew for once, or thought he did, what the chatter was about. The wrecked ship hauled in that morning was the talk of the town. Humans and cats and probably even the mice had found it a sad and unnerving sight. Anton hadn’t seen it yet, but Billy had told him about it when he stopped to chat with him earlier.

“When you see something like that, you know you and your brother were the lucky ones,” Billy said, and this struck Anton as true. To have been stranded on one ship and then rescued by another that happened across them on the great, wide ocean was lucky indeed.

But there were many kinds of luck. Theirs had felt sometimes like a special sort, the kind that might not be wise to push. Anton tried to enjoy the singing, but his mind kept returning to the message from Hieronymus and the shipwreck, arriving so close together. It felt like a sign, but a sign of what, he couldn’t guess.

The singing gave way to an argument between two bearded sailors. Anton slipped out of the saloon and headed home to the lighthouse. After a nap, he decided to have a look at the wrecked ship. As the early morning light brightened the sky, Anton rounded the quay and spotted Billy, Cecil, and that silly kitten Clive, who idolized Cecil, lounging in the shelter of the harbormaster’s doorway, where they could survey the wharf without being seen.

“Has the lad been out here all night?” Anton asked Cecil as he approached.

“He’s better out here in the fresh air than where you’ve been keeping yourself,” replied Cecil. “I can smell the saloon on your coat.”

“It wasn’t so great in there,” Anton agreed. “I thought I’d have a look at this wreck everyone’s so agog about.”

Billy pulled himself up with his customary huff. “It’s a cautionary sight,” he warned. “There was not even a mouse survived on her.”

“Don’t scare him,” Cecil said to Billy. “He’s got enough caution already.”

As they ambled down the wharf to the storm-battered wreck, Anton considered Cecil’s remark. It irked him, as he was well capable of taking risks if there was a good reason. Hieronymus was a good enough reason, though he was sure Cecil would disagree.

The three cats stood gazing at the broken spars, the smashed bowsprit, and the tattered bits of sail hanging from the yardarm. “Not even a mouse,” Anton repeated. Then, as the sun pushed up over the horizon and cast a golden sheen across the deck of the ruined ship, the brothers both glimpsed a slight movement and burst into laughter. A solitary little mouse came running shakily down the line from the ship. With a wild leap, he skittered past them toward the shelter of the warehouses. As he passed, Cecil put out a paw and took in a breath, but Anton chided him. “Let him go. He’s the sole survivor.”

Cecil chuckled. “Probably the last of his clan.”

The brothers leaned toward each other and bumped shoulders. That was how Hieronymus described himself—the last of his clan—and Anton hoped Cecil was remembering, as he himself was, how after losing his entire family the mouse had saved Anton’s life by slowly, tirelessly chewing through a water barrel on a derelict ship.

“Shall we go find him?” Cecil asked.

“I wish we had more to go on.”

“We’ll be the first cats in history taking travel tips from rodents.”

“But you’re willing?” Anton asked.

Cecil shrugged. “I’m curious about these landships. But I didn’t think you’d want to leave again.”

“I don’t,” Anton said. “I just feel obligated. I don’t think Hieronymus would send for us if he weren’t in real trouble. We’ll stick together this time, right?”

“As long as I’m the leader,” Cecil agreed.

“I’ll be the brains and you can be the brawn,” Anton replied.

“Our mission is as good as accomplished,” Cecil declared. “Let’s go tell those silly mice we’re booking passage.” The brothers sauntered down the dock to have a look at the Sea Song and plot the best strategy for getting aboard.

Anton wondered how their mother Sonya would take the news. He hadn’t gotten the chance to say goodbye last time, when he was impressed right off the docks in the daylight. As he and Cecil explained everything to her that morning outside the lighthouse, she was surprisingly calm.

“I’m proud of you for going to help your friend,” said Sonya, nodding. She looked from Anton to Cecil, smiling slightly, then stepped in close and touched noses with each of them. “Be careful.”

Three of the kittens, Clive among them, barreled out of the lighthouse, squealing and tussling. Clive spied Cecil and leaped onto his back, trying to wrestle him down, but Cecil stood sturdily and laughed. Clive slid off and sat between Cecil’s front feet.

“Your brothers are going on a trip,” said Sonya to the kittens, who immediately fixed their big eyes on Anton and Cecil.

“Can I come with you?” asked Clive, looking up at Cecil’s white whiskers.

“No, it’s too dan—” Cecil paused, as Sonya sent him a warning look. “We’ll take you along when you’re older.”

“Will you bring us back some stories?” asked another of the kittens.

“Of course we will!” Cecil boomed. “What’s an adventure without lots of good stories?”

Anton swallowed and looked at Sonya as the kittens cheered. She smiled, and winked at him.

Billy appeared on the path, puffing toward them. “It’s time,” he said.

Cecil and Anton crouched on the hard packed dirt between two fat barrels, waiting for the right moment. Sailors grunted as they lugged the last of the cargo up the gangplank and onto the Sea Song, while others shimmied up the lines to loosen the sails. The cats knew what that meant: she was about to cast off, and they needed to move. Cecil could see someone with a large and elaborate hat, probably the captain, perusing a bundle of papers at the stern. Another man, very thin and wearing a bright green scarf, stood directing the crew as they reached the top of the plank with their loads. A loose plan formulated in Cecil’s mind, and he raised a paw toward the thin man.

“He’ll be an easy one,” said Cecil. “He’ll probably be pleased to see us. Everyone likes a cat or two on board, right?” He stood and stepped out from between the barrels. “Come on!”

The brothers moved with quick feet through the bustle on the dock and paused, side by side, at the bottom of the gangplank.

“Volunteering for duty!” Cecil meowed, and they began to climb up.

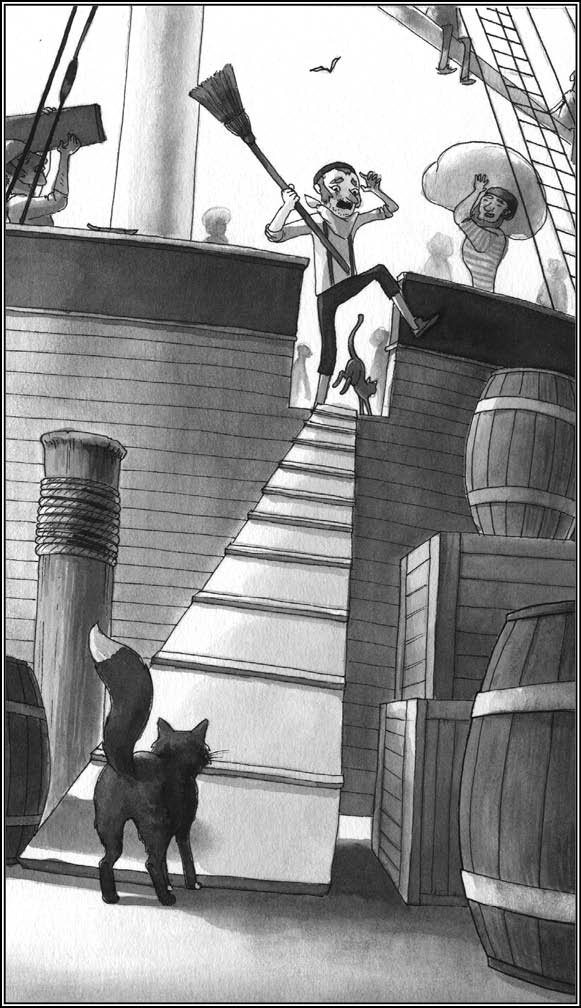

The thin man whirled toward the two cats and froze, an expression of horror on his face. He squinted, pulled the folds of his green scarf up over his nose, and began shaking his head rapidly. He stepped onto the plank, holding one hand up in front of him like a shield.

“He doesn’t look pleased,” said Anton, slowing a little.

“Follow my lead,” said Cecil. “We’ll win him over.” He hurried toward the thin man’s legs and rubbed against them affectionately, but the man shrieked and leaped away. Snatching up a broom from the deck, the man dropped the scarf from his nose and sneezed three times.

“What’s he doing?” Anton asked, ducking behind Cecil.

“I don’t . . .” Cecil sprang backward as the thin man swung the broom at his head. “Hey!”

The thin man sneezed again and pulled a handkerchief from his pocket to blow his nose, still aiming the broom at Cecil like a sword. The men high above in the ratlines hooted down at the scene, laughing. “The poor mate,” one of them shouted. “Allergic to everything but the sea!”

“I think he’s got a cold,” said Anton.

“Well, that’s not our fault.” Cecil retreated a few steps and looked down. The dark seawater eddied far below the plank. If either of them fell . . . best not to think of that. “Now I see why the mice are so at home on this ship—no cats.”

“We can’t get past him,” said Anton, crouching low on the plank. “Let’s go back.”

“We can make it. We’ll just have to do this together.” Cecil eyed the mate. “Here’s the plan. Next time he sneezes, you slip past.”

“Me?” Anton squeaked. “Why me?”

“Because you’re slimmer. Once you’re up, make him turn around, and then I’ll follow. Got it?”

“That plan is crazy. We’ll both end up drowned.”

Cecil glanced at Anton. “Think about Hieronymus.”

Anton looked past the thin man to the deck of the Sea Song. “It’s too far,” he said.

“You can do it, Ant Farm.” Cecil grinned at his brother.

The man let out an enormous sneeze, raising the broom for a moment as he did so.

“Go!” yelled Cecil.

Anton bolted under the broom and between the thin man’s legs. In an instant he was through. He’d made it!

The sailor opened his eyes and dabbed at his face with the handkerchief. Cecil stood before him on the plank, swishing his tail impishly. The man blinked at Cecil and stumbled backward. Anton let out a yowl from behind. The man cried out, turning sharply. The broom fell from his hand to the water below and he lunged to the side railing for balance as Cecil dashed past. More laughter rang out from the men on the masts as the two cats scrambled across the deck, darted into the first open hatch, and disappeared.

“It’s pretty dark down here,” whispered Anton.

Cecil squirmed next to him and sighed. “But you can still see, right? You’re a cat.”

“Well, yes,” Anton admitted. “Though there’s not much to see, really.”

The hold was only half-full, mostly crates and a few barrels. A stack of wooden boards was secured with ropes against one wall of the hold, next to the ladder to the hatch.

“I’m starving,” said Cecil, his nose working. “Nothing in here smells like food, except those berries.” He nodded toward some containers wrapped in burlap sacks in one corner.

“That’s why we stuffed ourselves with fish before we left, remember?” said Anton.

“That was ages ago. Who knows how long this trip will take? I’m heading up.” Cecil crept carefully to one end of the stack of boards and began to climb.

Anton raised his voice. “You’ll be caught by that sickly mate,” he called to his brother.

“Nah,” said Cecil, peering up into the darkness from the top of the stack. “It’s probably nighttime now, when most of them sleep. I’ll just look around for a few scraps.” He tucked his front paws under his chest and settled in to wait for someone to open the hatch. When that happened, Anton knew, Cecil would dash up the ladder and blend in with the blanket of night on deck.

“That stomach of yours is nothing but trouble,” muttered Anton. He closed his eyes, but he waited as well, listening along with Cecil. At last a sailor, swinging a lantern before him, threw the hatch open and climbed down to retrieve a small cask. Anton opened his eyes just long enough to glimpse Cecil slipping up and out like a shadow. For a big guy, he’s fairly quick, Anton thought before curling into a dreamless sleep, rocked by the motion of the ship across the moonlit sea.

Anton was awakened by a sound—a ripping, tearing sound nearby, followed by a slight smacking. Instantly alert, he crouched low, slinking past the crates on silent paws. Not a rat, he thought. Please not a big ugly rat trapped down here with me. He took a deep breath and peeked slowly around the crates.

On top of the burlap sacks in the corner sat the two mice who had brought the message from Hieronymus, feasting on blueberries. Anton blew out his breath and sat down, watching them. The gray mouse reached through the hole he had clawed in the sack and pulled out a fat berry, then turned to Anton.

“We meet again,” said the gray mouse, his pointed nose covered in blue juice.

“So we do,” said Anton. “How long a journey is this, anyway?”

“Not long,” said the gray mouse between bites. “We’ll arrive at the next daylight.”

The brown mouse sat stiffly atop the bag, keeping one eye on Anton as he ate. He leaned and whispered something to his sidekick that Anton did not catch.

“Right!” squeaked the gray mouse. “Almost forgot.” He turned to Anton. “There was another part of the message.”

“Another part?” said Anton, frowning. “Why didn’t you tell us before?”

“Your friend, the big guy.” The gray mouse winced. “He’s got a look in his eye, that one. Too dangerous, we had to go.”

“Never mind him. What’s the other part?”

The gray mouse held his berry, looking mystified for a moment. He consulted with the brown mouse quietly, then sat up tall. “Got it. Ahem. Hieronymus says he’s to be found ‘between the whale and the coyote.’ ”

Anton opened his eyes wide. “Between the whale and the coyote,” he repeated. “What’s a coyote?”

“No idea.” The mice began cleaning their faces with their tiny forearms. A thud on the deck above made them jump and they scurried away, knocking berries to the floor as they scrabbled.

The brown mouse paused to glance back at Anton. “Good luck,” he squeaked softly. “You’ll need it.” And the mice vanished into a crack in the wall.

Anton stepped forward to nibble on a few of the strewn berries. Alone in the dark hold, he felt his heart stutter in a way it hadn’t for months. Oh, yes, he thought. We’ll need it.