Another Sea

It all began,” Hieronymus said, settling himself on his haunches and clearing his throat for a long recitation, “when I was contacted by two agents from the well-known mouse network. Of course I’d heard of this group and their good works, as what mouse has not? But it was my first opportunity to see at close range the valiant endeavors they undertake all over the world to further the interests of our great community, so hard beset by cruel treatment by both humans and beasts. Their message was from a long-lost cousin I hardly knew I had, though he’d heard of me in his faraway region because of the sea adventures I’d undertaken with my friends Anton and Cecil.”

“You had sea adventures together?” Montana asked.

“Oh yes,” Hieronymus replied.

Cecil yawned and passed a paw over one ear. “Don’t get him started on that story,” he said.

“Right,” said Anton. “Just stick to the tale about your cousin.”

“Eponymus,” Hieronymus said. “Sadly I’ve yet to meet him. But his message was that he was enjoying life in a distant clime and that he hoped I might join him there.

“I had been thinking of relocating for some time, as I had no family in the vicinity of our port, so I decided to undertake the journey. The messengers met me at the ship and showed me a safe mouse-entry hole. The sea journey was uneventful and when I arrived at a large port city, the network had sent two scouts to meet me and escort me, first to a very fine dinner and then to the landship, where they helped me to select the best carriage. For the first few days all went well. Other mice, some who had made the trip more than once, got on and off, advising me of what to expect along the way. They suggested the best places to stop over and have a meal, and they were very clear about the timetables of the landships, so I was never uncertain about my progress.

“At last we came to the town where my cousin lived. I asked around until I was directed to his house, where I was met by a most pleasant mother mouse with two children. She told me that Eponymus had learned there was a great ocean at the end of the train tracks, as well as a fine city where every mouse lived like a king. His longing for sea air had been too much for him, so he had decided to make the move. ‘It’s not much farther on,’ this kindly mother assured me. ‘Only two days on the landship, and you can’t miss your stop because the track ends at the shore.’

“After resting for a day or two in this town, and rescuing the matron’s babies from a very obnoxious bird who had it in mind to make a lunch of them, I decided to follow my cousin to the fine city.

“On the next train things went very wrong. There was a fire in my carriage and I escaped by running along the roof of the cars. But alas, I descended abruptly through an unexpected opening and dropped right into a carriage designated for human passengers. I was alarmed at first, but no one saw me and it was very nice in there, with lots of room and good smells. I ran along the wall under the seats and jumped into an open basket that was full of bread and cakes. I ate until I was full, not at all worried about missing my stop, as I knew everyone would get off. This is the way to travel, I thought. I could see why humans are so keen on it.

“Then I fell asleep and when I woke up a lady and a little girl were staring down at me. The lady was screaming. The little girl smiled and slammed the lid shut before I could get out, and I was trapped. I was in that basket for a long time and when at last the cover was lifted, a great black paw reached in and grabbed me before I could escape. It was a man’s gloved hand and it dropped me into a cage.

“Naturally I began to plan my escape. Anton can tell you that I am not one to give up easily and I’m well versed on survival techniques, but this cage was a truly diabolical fabrication made entirely of metal with a latch I couldn’t open no matter how I tried. I was given food and water, and there was a device that I used for exercise—a wheel that allowed me to run without ever getting anywhere, which as you can imagine, is a very disheartening way to pass one’s time.

“After weeks of imprisonment, I thought of my friends Anton and Cecil and I decided that my last hope was to send a message to them through the network, using the only two landmarks I could see from the front and back windows of the house—the whale and the coyote. It was the parrot Dayo, a very intelligent though often difficult roommate, who told me the human name for the fearsome creature on the sign.

“And so I sent my message and waited. I had a good deal of time to think about my life, my family, and my future, and I was in a great despond to think I might end my days trapped in a cage at the whim of humans. I could not fathom why they would take pleasure in keeping a creature they otherwise recoiled from in horror locked up in a wire box in which they provided food, water, and exercise, enough to keep me alive, but they would not give me liberty. I had the feeling that something about my helplessness made them fond of me, but how could that be? In this awful state, near despair, I looked up at last to see my deliverance in the form of my two friends’ faces upside down outside the window. I can’t describe my joy at that moment, or the thrill of escape. And so I came to this place to spend a magical night in the company of cats, great and small. What a life I’ve had.”

Here the mouse ended his story, gazing at his audience with warm confidence. Cecil had drifted off to sleep early on, but Anton and Montana had stayed awake, curious to hear Hieronymus’s tale. In fact the Great Cat was wide-eyed and rapt with attention. Anton thought it was odd that such a powerful and solitary animal as Montana would be so fascinated by the story of a mouse’s travels. But then it dawned on him: solitary—that was the word. Alone up here on his mountain Montana was free and never afraid. But there was no one to tell him a story. And that was sad.

Imagine, dear reader, if there was no one to tell you a good story?

Anton also observed that the mouse network was a lot more efficient and helpful if the traveler in their care was another mouse. They had met and assisted Hieronymus at every point along the way, recommending the best places to find meals and making sure he had comfortable accommodations. Anton and Cecil had had to eat bugs and berries, take advice from dogs, and risk their lives careening around on hoofstock. Yet it appeared that everywhere Hieronymus went, he was welcomed by knowledgeable and helpful mice!

Anton smiled at Hieronymus and his attentive audience, the Great Cat. Cecil was snoring softly, and the only other sound was the mouse patiently answering a question Montana asked about his escape. Anton felt safe and strangely happy. For the first time since their journey began, he wasn’t homesick. In the morning he and his brother would set out with their little friend for the ocean at the end of the track. He was sure Cecil would want to go on. If there was an ocean, there would be fish. Fresh fish. That would be all Cecil would need to know.

A warm wind blew through the night, and the cats awoke to see tumbleweeds chasing one another down the alleyways between sheer faces of rock. Cecil felt dry down to his bones. He longed for the smell of sea air, the feel of the waves under a ship, the cool blue expanse. These mountains were interesting in their way, but too hard and dusty for a sea cat. So he was glad to hear that they would be journeying onward to another ocean, even if it meant more travel on trains.

Montana accompanied them as far as the edge of town and helped them find one last big meal to fill their bellies before they set off. The four creatures sat in the morning breeze for a while, enjoying the sunshine and cleaning their ears and whiskers with their paws, and then it was time to go.

“I wish you well,” said the Great Cat, gazing at each of them in turn. “In some ways I’d like to see what you are seeking—a great ocean. Your story has shown me that there’s much I don’t know about the world. But I fear that a cat of my size might attract a lot of attention.”

“It would be hard to hide you on the train, that’s for sure,” Cecil agreed.

“We can tell you about it when we come back through this way,” said Anton.

Hieronymus gave his friend a look both pensive and doubtful, but said nothing.

Montana looked down at Hieronymus. “I do most humbly thank you, small mouse, for rescuing me from that trap. I might have died there, were it not for you.” He bowed his head slightly.

Hieronymus flushed. “Happy to be of service,” he said quietly.

The Great Cat nodded thoughtfully. “Cats are wild beasts no matter how much time they spend around humans. And we must watch out for one another, care for each other when we can. Anton and Cecil came to rescue you, Hieronymus, as you have rescued them and now me. That makes you one of us, I think. In addition to your many mouse relatives, we are your family as well. Be safe.”

Montana lifted his great head and breathed in, catching a scent on the breeze, and then he bounded away toward the mountains. The cat brothers and their small mouse friend watched him go in silence. From beyond the hills far away to the east came a familiar pair of sounds—a high whistle and a low, rhythmic chugging—and they turned and hustled toward town to catch their train.

The train that pulled into the station trailed various types of carriages behind the engine, and the friends knew to choose an open box-like one and to avoid the many-windowed ones with people waving. Cecil allowed Hieronymus to climb on his back and hang on to his shaggy fur as the cats made the leap up into the carriage. The way the engine waited on the track, hulking and chuffing, reminded Cecil of Dirk and his bison friends, and he told Anton and Hieronymus that story while they rode.

For two days and nights they bumped and swayed along the track, the sights becoming stranger as they went. Steep climbs slowed the engine to a crawl and they wondered if it might stop altogether. Impossibly high bridges over deep gorges sent Anton scrambling to hide under the hay in their carriage until they were safely across. Cecil watched from the doorway one bright morning as the train approached a rocky mountainside without slowing, and one by one the carriages were swallowed up into a round black mouth in the rock until their own box was plunged into darkness and loud, echoing clacks were all they could hear. They huddled together, wondering what was to come, when the sunlight reappeared and the train continued on as it had, relentlessly rumbling down the track.

Cecil and Hieronymus became adept at dashing to find food during station stops—Cecil following his nose to a discarded meat pie or unattended leg of chicken, Hieronymus snatching a few berries or scattered grains, and once an entire wedge of cheese—while Anton stayed behind to sound the alarm if the train appeared to be leaving before the other two returned.

“Brothers! To me!” Anton howled from the station porch as the yard workers began closing the doors to the carriages. The three would dash to their box just in time and hide behind crates until the train began to move.

On the third day the train arrived at a big city with a bustling station to match, and when Cecil leaned out to check the ground ahead of the engine, he saw what they’d been waiting for.

“This is it, mates!” he said with a grin. “There’s no more track past this station. We’ve arrived at the end.”

“Can you see the sea?” asked Hieronymus anxiously.

Cecil looked again, stretching his neck, then working his nose. “I can smell it, for sure. Let’s go!”

They walked to the roadbed where Cecil’s nose led them and saw an inlet filled with sailing vessels and surrounded by busy dockside activity—but no wide ocean. Hieronymus drooped with disappointment.

“But where could it be?” he said, twisting his tail. “My cousin was sure there was a second sea here.”

“You know,” said Cecil, rubbing his ear with a paw. “The mouse network isn’t so great on details. Maybe this is what they meant by sea.”

“Oh, surely not,” scoffed Hieronymus. He gazed around the inlet, frowning. “On the other hand, Cecil, you might be right.”

Many people from the train, their bags and boxes in tow, had also made the trek down the road to this spot. They gathered along one pier as if waiting for something. At the far end of the inlet, a narrow waterway disappeared around a bend, and Cecil spied a type of vessel he’d never seen before emerging from there: a large, wide boat that seemed to move not with sails, but with huge wheels that churned and slapped at the water on each side. The boat approached the pier amid a great splashing mist.

“Will you look at that?” said Cecil. “It’s like a cart, rolling on top of the water.”

The churning slowed and stopped, and the wheel boat pulled even with the pier. Many humans disembarked down a steep ramp, after which the other waiting humans boarded and the ship pushed away. The cats watched as the wheels propelled it across the inlet and around the bend again.

“I have a feeling we should have gotten on that ship,” said Hieronymus. “Perhaps it keeps going to the ocean.”

“Let’s wait and see if it comes back, like the fishing boats do,” said Cecil. “In the meantime, this is the perfect occasion for a snack.” He bounded happily down to the docks and soon returned with a crusty loaf of bread in his jaws for them to share. They tucked themselves between two buildings and dozed in the sunshine for a while, until Anton’s ears pricked up.

“There’s the sound again,” he said. “The splashing of the wheel boat.”

And sure enough, there it was, paddling across the inlet like a duck. This time the friends snuck aboard and hid under a tarp covering a dinghy on deck. The wheel boat set off and navigated a narrow band of water for half a day, arriving at a similar pier in an even bigger city than they had left. The most thrilling part was the view that opened before them as the boat docked and they emerged from the tarp.

“Oh, my whiskers!” gasped Hieronymus. “The story was true, after all.”

A wide, blue ocean stretched all the way to the horizon, the crests of the waves lit by the setting sun. A pod of dolphins played in the distance. Great ships plied the waters, their sails raised, their flags snapping. The nearby harbor was filled with the masts of schooners, barques and brigs, clippers and sloops, and the shorebirds swooped and gamboled in the wind. Above it all floated a welcome aroma: the briny tang of fish. The familiar feel of home washed over the three friends as they stood on the deck for a long moment.

Then quick as a wink they slipped down the gangway and through the crowded streets until they arrived at a high cliff overlooking the shore and the sea beyond. They stood side by side, overwhelmed by the sight, grateful that they were together and in one piece after all that had happened.

Finally Hieronymus heaved a contented sigh. “In all my days,” he said softly, “I’ve never seen the sun dipping into the ocean. Only rising out of it. We must be on the other side of the world.”

“Is this sea as big as the other sea—our sea—do you think?” Anton asked, his gaze sweeping over the water.

“Nah, couldn’t be,” said Cecil, shaking his head. “Our sea is huge.”

Hieronymus stroked his whiskers thoughtfully. “Does this sight make you two eager for more adventures?”

The brothers answered at the same time. “NO,” said Anton. “YES,” said Cecil.

Hieronymus chuckled. “That’s what I thought you’d say.”

“What about you?” asked Anton. “Now that you’re free, will you go home again?” He sounded unabashedly hopeful.

“I’m getting on in mouse years, Anton. This may well be my last journey.” The cat and mouse exchanged a glance, and a look of understanding passed between them.

Cecil was distracted by something on the beach below the cliff. “What in the name of the Great Cat is that ?”

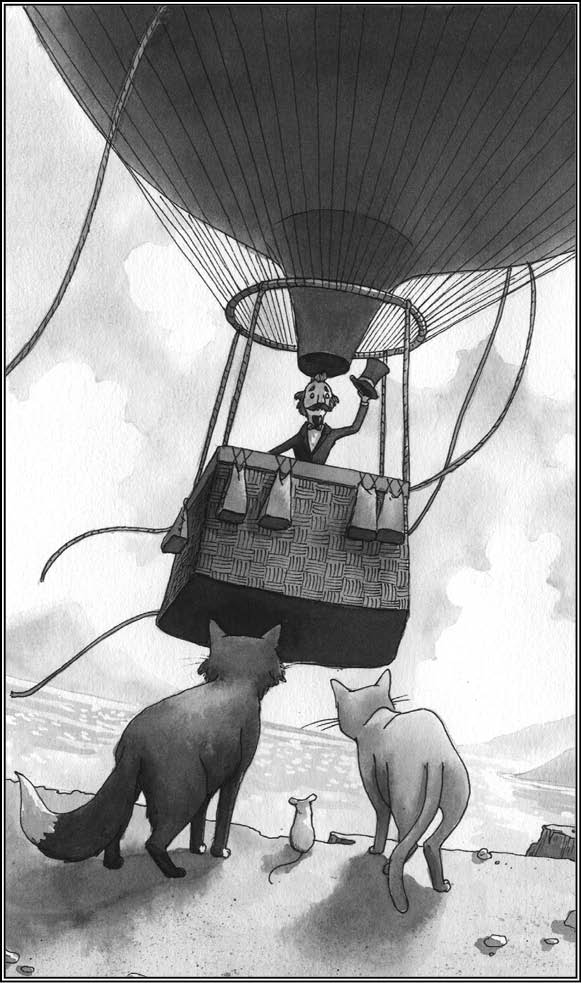

The other two peered over the edge, following his gaze. Rising slowly above the sand close to the cliff wall was a contraption so unlikely that it left their jaws slack. An enormous basket, of the kind that fishermen used to store their catch but many times larger, swung gently in midair, kept aloft by a giant swollen balloon. The basket had no lid and held a man who watched the bright blue balloon carefully, pulling on the various ropes that connected the basket to the balloon, and tending to a stove that sent up a great whoosh of fire. As the basket ascended Cecil could see inside, and to his surprise it was furnished with chairs and a table spread with a cloth and what looked like sandwiches on a plate. Very slowly, chuffing rhythmically, the whole assembly rose straight up in front of them. As it passed the man spotted them and waved.

“Amazing!” cried Cecil. “In the space of one day I’ve seen two astounding things—a wheel boat, and now this—a giant basket floating on air. I like this place!”

“I like that we’re together in this place,” added Anton.

Hieronymus smiled. “We’re agreed, then. We’ll try our fortunes on this end of the world for a bit.” His black eyes gleamed and he grasped a pawful of fur on each brother.

But Cecil was gazing up at the big balloon as it caught the wind and bobbed landward. His eyes were wide and his heart throbbed with excitement.

“Cats in heaven, it’s an airship,” he said softly. “What a way to travel!”