Shriek and Growl

It had seemed like a good idea at the time.

After all, Cecil had visited a ship’s galley before. He knew it was the place where food was prepared for the crew, often haphazardly, where chunks of meat or fish might be found wedged between barrels, and drips of stew could be lapped up from the floorboards next to the stove. Perhaps part of a hard biscuit to nibble on, but that wasn’t real food, in Cecil’s view. The galley of the Sea Song was empty of humans, as he’d hoped, though a lantern still burned on the sideboard, and he found a small wedge of hard cheese and some dried peas for his snack. As he sat and cleaned his face, he could hear the clickings and scurryings of rodents in the walls. A shame, he thought. A good ship’s cat could whip this place into shape in no time.

There was a stomping down the steps toward the doorway. The only problem with the galley, Cecil suddenly recalled, was that there was just one way out. He caught a quick glimpse of a sailor stepping in with an armload of tin plates, and he dashed into the tiny larder, squeezing himself behind a tall sack. The sailor dumped the plates into a wooden tub, then picked up the lantern from the sideboard and walked out again, pulling the door shut behind him.

Cecil groaned. He really should have been more careful. Now he was stuck, and Anton would worry. “Ah, well,” he said to himself as he made his way through the darkness over to the tub to lick the plates clean. “It’s a nice place to be stuck.” A little snooze on top of the flour sack, and he’d wake up refreshed, and the crew would have to eat again sometime.

But hours passed and Cecil felt the ship slow and then stop. The thudding and banging of dockside activities began, and he paced in the galley. Were they not even going to come in to prepare that foul black liquid they drank at all hours? He positioned himself near the door and listened to the sailors tromping back and forth on the deck above. He tried to think like Anton. What would he do? Anton wouldn’t venture off the ship alone, so Cecil would have to get back to the hold to find him—as soon as somebody opened this blasted door.

Heavy boots tramped across the deck above Anton’s head, and he could hear muffled voices shouting and answering as the steady rolling of the ship quieted. Anton guessed they were coming in to dock, but Cecil hadn’t returned. The hatch hadn’t been reopened, so he was still up there, somewhere. Should I get off the ship by myself ? Anton wondered. What if Cecil’s gotten himself trapped, or captured?

The hatch creaked open, spilling in sunlight. Anton pressed himself against a barrel as several crewmen climbed down the ladder and began hoisting crates onto their shoulders to carry up again. He slipped behind the men and crossed the hold. As quietly as he could, Anton scaled the stack of boards as Cecil had done and crouched to wait for his chance to escape.

“Aw, something got into the berries,” said a sailor in the corner, holding up the torn bag with one hand. The others stopped and scanned the grimy walls for a moment as if they might spot the culprit. Anton put his face between his paws and tried to flatten himself along the boards. The sailors shrugged and bent to heave more cargo, and Anton saw his opportunity. With a running leap he sprang to the ladder and scrambled through the opening without a sound.

Out on the deck, Anton blinked in the sunlight and gasped.

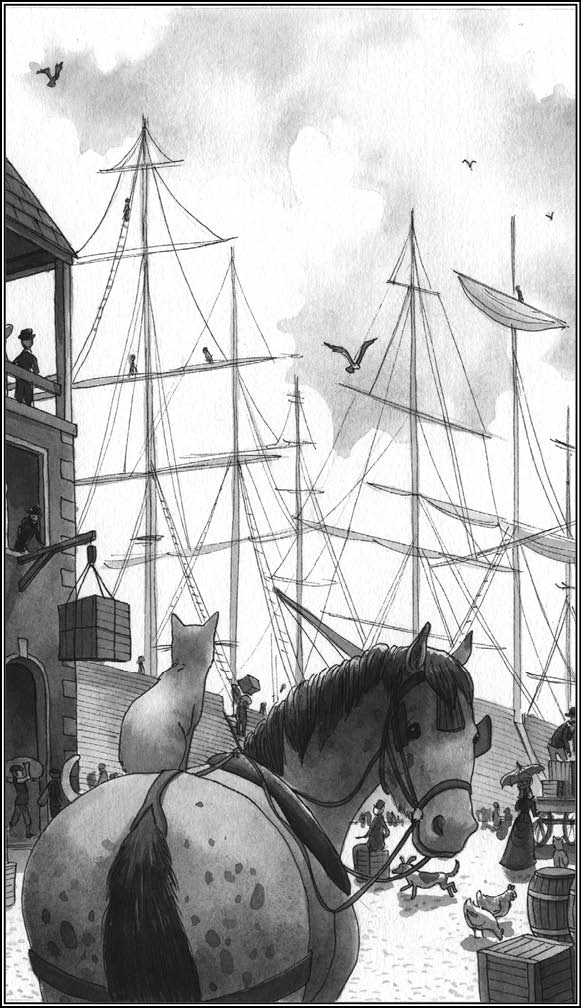

Before him was a wharf, and beyond it was a city bigger and busier than Anton had ever seen or dreamed of. Horse-drawn carriages and loaded wagons crowded the street. Dogs, cats, and chickens wove among the legs of people thronging everywhere. Children laughed and ran past adults selling knives, bottles of liquid, candles, pots and pans, all manner of clothes, and food in roadside stands. Behind all of them rose tall buildings along blocks that seemed to stretch outward forever. The noise hit Anton like a wave over the bow—the shouting and neighing and rumbling, all unceasing. The chaotic scene made the unpredictable ocean seem calm and inviting by comparison.

As Anton stood, mouth ajar, taking everything in, he heard a loud sneeze from behind him. He flinched and looked back, straight into the watery eyes of the first mate who’d blocked their way. The mate pulled the green scarf covering his nose down long enough to bellow, “Off my ship this instant!” Wielding the broom, he charged at Anton.

For a second Anton froze. Should he stay and try to find Cecil, or disembark and wait for him on land? No time to decide before the mate was upon Anton, shooing him frantically toward the gangplank. Anton dodged to one side, glancing toward the bow and then the stern for any sign of a big black ball of fur, but the mate hustled Anton down the plank at broom-point.

In the middle of the muddy roadbed, Anton sidestepped cart wheels and the boots of strangers. He swiveled his ears, listening for Cecil’s voice in the crowd. He dove into the shadows behind one of the stalls and surveyed the hectic activity on the street, a knot of fear twisting in the pit of his stomach. He’d lost Cecil already and had not the first idea where to go from here.

The Sea Song still rested against the dock, her gangplank empty now, her sails wrapped tightly around the crossbars. Anton gazed at the ship in a panic. It was the last connection he had to anything familiar, and he felt its pull. Then Hieronymus’s voice floated through his mind, and Anton remembered being trapped in a cage at an animal market on a distant island with his friend. The mouse could have escaped easily to save himself, but he refused. I’ve pledged my troth! he’d declared, holding up a paw. I will not leave a friend in danger. Anton shook his head sheepishly. Hieronymus would not give up so easily.

The noise of the bustling town settled around Anton, and he began to hear distinct sounds in the din. Crying children, screeching shorebirds, shouts of men’s laughter, and the creak of wagon wheels. One sound he could not place. It hung heavy as a storm cloud above and below and among the others. Anton could feel its vibrations in his rib cage, but it was not the pleasing music of the saloons. This was a dense, chuffing sound, like bursts of wind against the sails, or an enormous creature taking slow, panting breaths. Anton didn’t know what it was, and it terrified him.

At long last the cook and the cabin boy burst into the galley, not even noticing as Cecil scampered behind their legs and up the steps to the main deck, awash in sunlight. He hustled to the hatch, which lay wide open, and peered down into the hold. His stomach lurched. The space was empty; all of the crates and barrels and even the stacks of boards had been carried out. “Anton!” Cecil’s voice echoed in the hold. But he knew his brother was gone—there was nothing left to hide behind.

Cecil straightened up. What now? Only a few crewmen were about, including the sneezy mate, clutching his dastardly broom and talking with the captain down by the ship’s wheel. There were lots of other places Anton could be hiding—under tarps or inside coils of rope, down in the fo’c’sle, up in the ratlines, but . . . Cecil’s nose began to twitch.

What was that smell?

He turned his head slowly toward the pier, his eyes narrowing and his nose working furiously. Among the people and carts and animals crowding the roadbed, Cecil detected the scents of roasted meats, freshly baked bread, simmering stews, and an ocean of fish, all close at hand, some of it in plain sight as humans behind counters held steaming packets out to others passing by. On their own, his paws began moving toward the gangplank.

“Surely Anton would go this way,” Cecil murmured, breaking into a trot at the sound of the mate shrieking behind him. “Any cat worth his salt would.”

He reached the docks and continued right on, his nose in the air and leading the way. Anton must be hungry, Cecil reasoned. He’s had no snack. So what would he . . . Cecil turned and sprang out of the path of a horse pulling a loaded wagon. That was close. He recovered his balance, then yowled as his tail was smashed under the boot of a little boy running past holding several steaming sticks above his head. Cecil bared his teeth to hiss at the boy, but noticed that he’d dropped one of the sticks, and it smelled like something with great potential. What luck! The stick ran straight through the middle of several chunks of fish. Cecil quickly clamped one end of the stick in his mouth and darted behind a tree on the far side of the roadbed.

He had just figured out how to hold the stick down with both paws and pull the fish away with his teeth when he felt the close presence of another creature. Cecil lifted his eyes to see a small orange cat creeping toward him, low to the ground. It was just a kitten really, a male with a skinny tail and big ears, and he froze under Cecil’s glare. Cecil continued gobbling down the fish and the kitten advanced smoothly, like a little hunter. Finally Cecil stepped away and began cleaning his paws, leaving a fat chunk behind on the stick. The kitten dashed forward and leaped upon the fish, wrestling off little bites while gazing up at Cecil.

“I haven’t seen you before,” said the kitten with his mouth full. “You just get here?”

“That’s right.” Cecil nodded. “Passing through.”

“Where you going?” asked the kitten.

Cecil paused. “To rescue a friend, you could say.”

The kitten nodded. “That’s nice of you.”

“Maybe,” said Cecil, turning to the kitten. “Say, do you happen to know anything about landships?”

The kitten sat up, his round eyes wide, his long pink tongue licking the fish from his lips. “Landships!” He thought for a moment, then shook his head. “Nope. What are they?”

“They’re the way we need to get where we’re going,” said Cecil, suddenly remembering Anton.

The kitten looked around. “Who’s we?”

Cecil had opened his mouth to explain when a high whistle blew in the distance, followed by a deep, rasping chug, and then another, and another, slow and even. “My whiskers!” said Cecil, his ears cocked. “What is that?”

The kitten gave a tiny sigh. “That,” he said, solemnly, “is something we call rolling death.”

Cecil eyed the kitten closely. “What do you mean, rolling death? That sounds horrible!”

“It does, because it is.” The kitten bobbed his little head up and down. “It’s a huge carriage that moves without anything pulling it, and it’s loud and ugly, and my mom says if you get too close it’ll roll right over you. She says that’s how Uncle George disappeared.”

“A carriage that moves without anything pulling it,” said Cecil softly. “This I’ve got to see. And it’s over that way, you say?” he asked the kitten, pointing a paw.

“Well, yes, but don’t go over there!” said the kitten, arching his back above his skinny legs. “Didn’t you hear the part about it squishing you, and Uncle George?”

Cecil smiled at the kitten knowingly. “What do they call you?” he asked, appraising its orange fur. “Pumpkin?”

“Herman.”

“Well, Herman, I say don’t be a chicken, be a cat! Get out there and have an adventure!”

Herman swiveled his ears at another blast from the whistle. He shook his head. “No thanks. Too dangerous.”

“Fair enough,” said Cecil, turning to leave. “But if you see my brother Anton passing through, be sure to introduce yourself. You two have a lot in common.” He gave a side-to-side swish of his tail and disappeared into the crowd of legs on the roadbed.

Anton was overpowered by the strange chuffing sound. He backed up cautiously, drawing his head in as if to avoid a blow. A shriek like a giant hawk tore through the air in front of him at the same time as a blast of wet, hot air struck him from behind. Without thinking, he whirled about, claws out, his jaws wide to issue a warning hiss of his own. He was facing two wet, black nostrils the size of his head. Before he could figure out what he was seeing, the nostrils flew up before him and he realized it was a horse, now stretching his big head skyward, his glassy eyeballs rolling down at Anton and his hairy lips quivering.

“Whoa, whoa there,” said the horse. “Don’t put those claws in my nose, for neighing out loud.”

Anton sheathed his claws and ran a paw over his mouth to smooth his whiskers. He’d seen horses on the docks at home, but he’d always tried to steer clear of them, as they were clearly dangerous. This was the biggest horse he’d ever seen, and the hairiest. Even his hooves were draped in a deep fringe of fur. Anton had never spoken to a horse before, but this one looked so upset he thought he’d best be polite.

“Excuse me,” he said. “You took me by surprise.”

“Well, that’s no reason to threaten somebody with claws in the nose.”

“I’m afraid that’s not entirely in my control,” Anton explained.

The horse worked his lips, as if thinking over this reply, gradually lowering his head. “You mean the claws just come out automatically?”

“Sometimes,” Anton replied. “I can make them come out when I want to, but if I’m frightened, it’s not something I think about. I just know I may need them, I guess.”

“When I’m frightened, I run as fast as I can,” the horse said. “And I guess I don’t really think about it.”

“I’ll bet nobody gets in your way,” Anton observed.

The horse seemed to find this amusing. “No,” he said. “I’m a big guy. No human’s going to catch me, running on those flimsy feet they have.”

Anton took in the leather strips and wooden poles that strapped the horse to a wagon loaded with heavy-looking bags. “My name is Anton,” he said.

“I’m Solitaire,” the horse said. “Or that’s what my mother called me. My master calls me Nutmeg. We work here, most days. Do you live around here?”

“No,” Anton said. “I just got off that ship.” He lifted his chin to indicate the gangplank of the Sea Song, from which a steady stream of men and crates now issued. “I was with my brother, but we got separated and I can’t see anything in this crowd.”

“What’s he look like?” Solitaire asked.

“He’s bigger than me, black, white whiskers, long fur.”

The horse looked out over the crowd, moving his head slowly from side to side. Anton noticed something he surely knew but had never thought about before, which was that a horse couldn’t look at what was in front of him because his eyes were on either side of his head. “I don’t see him,” Solitaire said, bringing his head down close to Anton.

Anton tried looking between pairs of legs, around long skirts, and through the wheels of Solitaire’s wagon. “I don’t know how I’m going to find him.”

“You want to get up on my back?” the horse suggested.

Anton was surprised. He looked up at Solitaire’s wide back. The view from there would undoubtedly be worth having, but even at a run, he wasn’t sure he could make the leap. “I don’t think I can jump that high,” he said.

“Well if you can sheathe those claws, I’ll put my head down and you can walk up my neck. You can hold on to my mane if you need to—that won’t hurt me.”

Anton studied the horse. It was definitely doable. “That would be very kind of you,” he said.

Solitaire lifted his upper lip and forced out a startling blast of warm moist air from his nostrils. “You’re a polite little creature,” he said. “I like that.” Then he lowered his head until his mouth nearly touched the ground. “Jump on,” he said.

Anton, conscious of his claws with every step, dashed up Solitaire’s neck, past his shoulders to his wide, flat back. There Anton sat, curling his tail around him. It was amazing, comfortable and roomy—there was space to stretch out and take a nap up there. The horse’s fur was smooth and had a pleasant scent, something Anton never would have expected. And he could see clear across the wharf. “Wow,” he said. “This is great. I can see everything.”

Solitaire swerved his neck around so that he could see his new passenger. “It must be hard to be so small,” he said. “You never get a view.”

Anton looked this way and that, trying to spot a black cat with a white paintbrush tail, but there was too much activity to focus on one spot for long. Nearby was a line of booths where people crowded, many carrying baskets laden with food. Anton thought that might be a likely spot to look for his brother.

Solitaire followed his gaze. “That’s a good place; humans go there and get all kinds of stuff to eat. My master goes there most days and sometimes he gets me an apple. I really like those.”

As Anton watched the milling crowd, he spotted a child standing next to a basket and behind a woman who was talking with one of the vendors in the stalls. The child was pointing at him and calling out something he couldn’t hear, but the mother did, and turned to see what was wrong. She glanced up at Anton—a cat on a horse, yes, that was amusing—and then resumed her conversation as the child continued to point and crow joyfully. Then . . . But no. It couldn’t be!

Anton recognized the toddler: it was the baby from that ship, the one on which he’d met Hieronymus, and on which they had both nearly starved. The child’s mother was the kind woman who had made a bed for Anton. One strange morning, he and Hieronymus had awakened to find that mother and child—and all the other passengers on their ship—had disappeared, leaving Anton and Hieronymus alone and adrift until their miraculous rescue. But here they were, mother and child, safe and sound in a busy town, and the baby recognized him. This comforted Anton, but it reminded him of his own mission to get to Hieronymus.

Anton shifted his paws and looked out in the other direction. In the distance he could see a long roofline and before it clouds of white smoke, but a small building in between blocked his view. Then he heard it again, that loud chugging sound, and after that—so unexpected and loud that he stood up on all fours, ready to leap to the ground—a shrill whistle tore the air.

“What’s that?” Anton exclaimed.

“Calm down,” the horse advised him. “It’s the horseless carts. That whistle means they’re about to start moving.”

“Where do they go?”

“I’m hobbled if I know. But the bigger question is how do they go. They just make a lot of noise and of course they have wheels—you’ve got to have wheels—but nothing pulls them as far as I can see. And they’re dangerous.”

“Are they ships?”

Solitaire raised a hoof and pulled his head forward so that the straps grew tight on his neck, making a snuffling sound with his nose. “Ships,” he said. “No, they’re not ships. Ships go on water. These go on land.”

“Landships,” Anton concluded.

“That’s good. You could call them that.”

“It’s what the mice call them,” Anton said.

“Mice!” Solitaire raised his head and cast a wild eye at Anton. “One thing I don’t like is mice. They scare the hooves off of me.”

Anton smiled at the idea of an animal Solitaire’s size being afraid of a mouse, but he didn’t say anything, because he felt certain the horse had just set him on the track to find his brother.

“Try talking to the mice,” Anton said. “Sometimes they understand.”

He took another long look around, back toward the ship—he could see the sailors pulling in the plank—then across the wharf to the food stalls—the baby and mother had moved on, no cats were in sight—and then along the buildings that stood between the wharf and that thick column of white smoke. “Cecil will go to the landships. He may be there already.”

“I take it you’re coming down,” said Solitaire.

“I am,” he said. “I can’t thank you enough.”

The horse lowered his head and Anton descended in two bounds. “I hope you find your brother,” the horse said.

Anton nodded. “I’ll be a sad cat if I don’t.”

The horse brought his big head down close and touched Anton’s back with his warm nose. “Good luck to you.”

“Goodbye,” Anton said, and he dashed across the dirt road to the shelter of another wagon parked alongside a shed. When he looked back he saw the horse standing, one hoof cocked and his long neck relaxed, his eyes closed, waiting patiently for his master to come back. Anton wondered about Solitaire’s life. He seems content enough, though he can’t go anywhere without his cart. I hope his master buys him an apple. And then he heard another shriek from the landship and took off in the direction of the sound.