One Moonlit Night

Anton heard Cecil’s shout and then the murmur among the human passengers who sounded amused by what they had just seen. His heart sank and he pressed his back close to the trembling wall of the carriage as the train picked up speed. They were not, evidently, about to arrive at the next stop. Anton thought that Cecil had probably survived the expulsion; he was good at falling into and out of trouble. He recalled his brother’s tale of swinging on a rope from one ship to another with a little bag containing a valuable stone clamped in his jaws. But even if Cecil was fine, how would he manage to get to the next stop? He wouldn’t have trouble finding it—just follow the tracks—but suppose it took days and there was nothing to eat?

Anton longed to get out from under the seat and look out the window, just to have some idea what was going by. Was it towns or just the endless fields of grass they’d seen in the early stages of their journey? He reasoned that it might not be a good idea to get himself thrown off as well, especially as the train seemed to be moving from a pleasant jogging trot to a full-out gallop. The whistle blew, the walls vibrated, and the rattling of the metal connections between the carriages sounded like they might just come apart. Anton closed his eyes tight, made himself as small as he could, and waited for whatever came next. He hoped the train stopped someplace with food and not so many hot, jostling, constantly talking humans.

He dozed, his tongue out, the pads of his paws sweating from the heat, and when he woke it was because the passengers were moving about, taking down their hats and jackets from the hooks overhead, milling in the aisles and exchanging pleasantries. They sounded as eager as Anton was, stuck under a bench, for this train to arrive at a destination. When the whistle blew, the train began to slow down and the door at the end of the carriage was thrown open by a man who shouted something. Yes, Anton thought. This is it. Just wait until all the passengers were out and then make a dash for it.

It didn’t take long before the boxes and bags had been hauled away and the last boots had exited at the end of the car. Anton ran to the doorway using the benches for cover, his senses alert to determine which way to turn for the nearest shelter. The Captain was standing on the planks outside, speaking to a lingering passenger, and didn’t even see the small gray streak run back alongside the train, then leap across the track and dash into some low grass on the far side. Once hidden from view, Anton crouched low and looked back at the scene. No one had seen him, and the humans were dispersing, going into the wooden building behind the planks or heading toward a line of horses and carts that were waiting to take them away.

Anton felt relieved to have his paws on solid ground with a thin, hot breeze blowing across his cheeks. Even though his mouth was so dry it felt like sand, he took a moment to wipe his face and ears to get the smell of the train out of his nose. Train travel was definitely not his preferred way to get anywhere.

The situation looked promising—lots of places to hide, the smell of food coming from a building across the tracks, and a long trough where a couple of horses stood sucking in water in that odd way they had of drinking. A number of buildings crouched together along the road, and beyond them a few more with wide yards and thin trees leaning over them. Dogs were all over the place, barking at one another, scratching and lounging in whatever shade they could find. In the other direction was grass, grass, and more grass, with a few trees scattered here and there. It wasn’t Lunenburg, where he could pass an evening listening to the sailors singing in the saloon or have a chat with old Billy about times gone by, but it was a town of sorts.

Anton darted back across the tracks and crept along the building until he was close enough to the horse trough to observe that it was leaking water at one end, making a nice puddle for drinking. He moved swift and low until he was under the trough and had a good long drink, his ears scanning back and forth for sounds of danger. Music and laughter issued from one building with a long awning across the front, but the songs were unfamiliar and the instruments strange; he couldn’t make head nor tail of it. Still, he crouched by the corner for a long while, listening to the crooning, feeling melancholy in the strange town.

His next mission, finding something to eat, was quickly accomplished when he observed a man come out of a side door to dump a bucket of scraps into an uncovered bin. After cautiously looking about in all directions, Anton made a dash across the dirt road and leaped right into the bin. He had his choice of cheesy bits, cut-up meats, and something white and pasty, but not in a bad way. No fish, but one couldn’t be finicky while traveling. As he ate he recalled the mountains of fish dumped on the wharf in his home town, glistening and flipping about, easy to cadge and delicious to eat. What was he doing in this place where there was more grass than water?

Anton finished his meal and leaped back out of the bin. He heard the shouts of the conductor, the sliding of doors and bustle of people getting back on, then the whistle tore through the air. Anton could never hear it without a moment of sheer terror. He stood his ground, but sank down on his haunches. The train pulled slowly away from the platform, heading for the sun, which was low now, sliding into a sky streaked with red and green. When the last car was well away, Anton crossed the tracks again without hurrying. There was no one around. He figured he would sleep in the grass so he wouldn’t miss the next train, on which, hopefully, his brother would have somehow caught a ride.

The grass was well over his head. With a little patting and tramping, he made a good hiding place, comfortable if a little prickly. It was a warm, clear evening and the stars were switching on as the light faded. He stretched out, resting his chin on his paws. Cecil, he thought. The big oaf. He was never much good at hiding.

“S’cuse me,” a voice said from somewhere in the grass.

Anton opened his eyes wide, without lifting his head. It was dark now, and late from the feel of the air. He had been deep in sleep, and for a moment he thought what he’d heard was just the rustling of the grass. There was a whisper of a breeze, but then the voice, which had a squeaky, oily quality about it, repeated, “S’cuse me.” The grasses just ahead of Anton’s face parted and a black nose poked through.

Anton drew his head back but still didn’t move. “You’re excused,” he said.

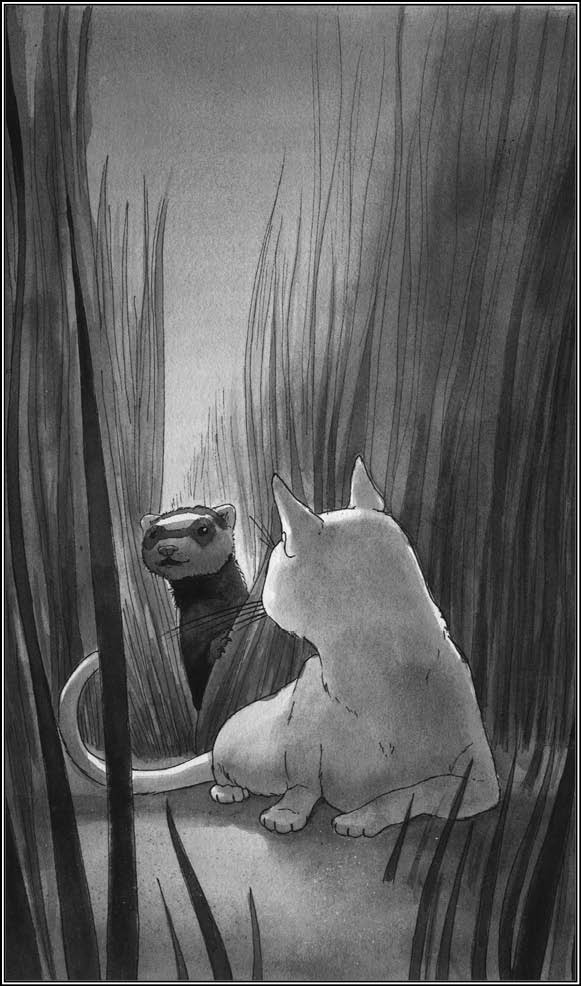

The nose twitched and there was a chuckling sound, then the rest of a small pointed face with black masked eyes, light cheeks, and pointed ears appeared. “Hey,” said the face. “Are you funnin’ me?”

For want of anything better to say, Anton replied, “My name is Anton.”

“Anton,” the creature said. “Howdy. Howdy do.”

It was like listening to humans, Anton thought. You had an idea what they meant sometimes, but you could never be sure. The creature emerged entirely now and sat down, staring with his beady eyes, patting his full belly, cleaning his sharp cat-like teeth with the pointed end of a long stalk of grass. But he wasn’t a cat, Anton was sure of that. He had a low, slinky, tan body and a bushy tail with a black tip. His shoulders, legs, and feet were black and his paws were definitely not cat paws. His neck was too long; also his head was too small.

He was larger than Anton by half, but he had a daffy look about him that wasn’t threatening. Suddenly whatever he was leaped straight up in the air and came down on the other side of Anton, disappearing briefly into the grass. Then he reappeared, his head emerging and sinking again, his back arched, then stretching out long, tearing through the grass in a wide circle until he came back and took his seat.

“You wanna play?” he asked.

“I don’t think so,” Anton said.

“Aw, come on. You chase me, then I chase you.”

It occurred to Anton that if he chased this silly animal, he would be able to catch him, and then where would they be? “I’m too tired,” he said. “I’ve been traveling on the train and I have to wait here for my brother.”

“Gotcha,” said the creature. “That’s my name. Gotcha. Ain’t that a scream?”

Anton smiled. It was a funny name. “I take it you’re from around here.”

“Sure,” said Gotcha. “My family lives over yonder. I got a brother, too, and two sisters. Momma died last year.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. Please accept my sympathy.”

“Thankee kindly,” said Gotcha. “Momma was one fine ferret. Nothing she couldn’t find if’n she wanted to find it.” Anton noticed that the ferret’s eyes squinted a little, and he sniffed. But then he shook his head and swallowed hard. “I know yer some kind of a cat,” he said. “But yer not very big.”

Anton drew himself up at that. “I’m not that small.”

“Compared to the cats we have around here, yer just a little sprout. They’re bigger’n you when they get born.”

“How big do they get?”

“You want to see some of ’em? There’s a family over yonder up that hill.”

“No thanks. I want to stay close to the tracks because I think my brother will be on the next train.”

“Well, that might be tomorry night and it might be the next, but it surely won’t be tonight. They don’t come through here but once’t every coupla days.”

“You’re sure about that?”

“Sure as shootin’,” replied Gotcha.

“Well . . .” said Anton.

“Come on along,” said Gotcha. “You’ll be right tickled to see the big baby cats. They’re just startin’ to try to hunt a little, chas’n’ crickets and like that. They’re mighty cute now, though they won’t be when they git growed.”

Anton looked toward the hills. He felt wide awake now and curious about this place with its strange inhabitants. If no train was coming anytime soon, he might as well check out the sights. Gotcha seemed an amiable sort of fellow, as goofy as Cecil and just as eager for some fun. And he clearly knew his way around, so Anton would have no trouble finding his way back to the tracks.

“Okay,” Anton said. “You lead the way.”

“Catch me if you can,” Gotcha squeaked, and took off through the grass, flattening it like a wagon wheel. Anton raced in his tracks—it was easy enough. The ferret had a loping gait because he was so long, and though he was pretty fast, Anton could easily have passed him. It felt great to race through the night after days of being cooped up in the train carriages. The moon was fading and the grasses hummed with those crickets the youngsters were doubtless chasing. Anton thought of his little brother Clive, who was almost grown now but still idolized Cecil and would sit and listen to his exaggerated sea tales for hours on end. The grasses thinned, and there was a slow rise to chalkier soil. Before a line of ragged-looking trees, Gotcha slowed to a trot and Anton drew up beside him, breathing in the warm night air.

“They play over by that little stream,” he said. “The momma goes out hunting and leaves them there. They don’t wander far. They know she’s strict about that.”

Anton perked up as they approached the cracked mud banks of the stream. “Any fish in there?” he asked.

“Not much. Frogs though. The tadpoles ain’t bad eatin’, but I don’t like ’em once’t they get legs.”

Anton nodded. He completely agreed with this assessment of amphibians as food items.

Standing on his hind legs and looking in all directions, Gotcha stretched his long neck and body up, his forelegs dropped at his sides. He was quite tall, Anton noticed. He could probably see right over that grass when he stood like that.

“I see ’em,” Gotcha said. “Right down on that bank.” He gave Anton a sidelong glance. “We best be careful now. We might not want to be hangin’ round her babies when that Momma comes down from the mountain, know what I mean? She could up and lose her temper if she sees us too close to ’em.”

Anton smiled. “How big is she?” he asked.

“You’d be about two bites, I’d say.”

Anton followed as Gotcha ambled along. They could hear the cubs now, making low mewing sounds and fake roars. As they descended the bank Anton saw them, and it was true—they were enormous light tan kittens covered with dark spots. They had striped foreheads and bobbed tails, and oversized furry, pointy ears. One was crouched, prepared to attack something in the water, and the other was teetering on a large stone, looking down on his brother and about to pounce upon his back.

“Lookit,” said Gotcha, as the brother cubs sprang at once and wound up rolling together into the shallow water. “I remember when I used to play like that with my brother.”

“Me, too,” said Anton.

The cubs had scrambled out of the water and were chasing each other back up the bank. “Watch out, watch out,” said one.

“You can’t get me,” said the other. They weren’t looking where they were going and had to dodge rocks and tree trunks on the fly. They were heading straight for their audience of cat and ferret. Anton looked on, much entertained, but as the cubs came together and play-attacked each other, rolling in a furry ball of tails, heads, and paws in the dirt, Anton spotted something just beyond that made him catch his breath.

It was a large snake, its body coiled, its head raised, watching the cubs coldly as they drew closer and closer.

Gotcha saw it, too. “It’s a durned rattler,” he whispered. No sooner had he said this than a strange shaking sound, like nothing Anton had ever heard, rose from the reptile’s body. The sound made Anton bare his teeth and hiss.

Gotcha’s mouth squinched up in a knot and he leaned forward on his black paws. “We got to do somethin’, Anton, or those cubs is done for. You take the back, I’ll get the front,” he said. “Just get a grip and pull.”

“Gotcha,” said Anton. And it was not until they were both streaking into the clearing that he realized he’d said the ferret’s name.

The cubs looked up from their play to see a very small cat and a large ferret covering ground like two lightning bolts. They backed away, letting out high-pitched cries of alarm.

The snake never knew what was coming. Gotcha dove onto the reptile’s head from behind, and as the scaly body uncoiled, Anton caught the other end and bit hard, pulling back with all his strength. When the snake was stretched out between them, Gotcha released its head and the long body rose high in the air. Anton leaped back, turning his head to one side, and let go of the tail. The snake sailed through the air, unable to coil itself, and came down with a crack against a rocky outcropping, where it paused for only a moment before slithering with surprising speed in the opposite direction.

“Holy Mo,” said Gotcha. “That’s the first time I seen a snake fly.”

The cubs came running then, shouting to their rescuers. “You saved us, you saved us! He was going to bite my brother. Momma said those rattlers are so dangerous. You saved us! Wait till we tell Momma.” As they calmed down and had a good look at Anton and Gotcha, their eyes grew wide.

“What are you?” the bigger one said to Anton. “Are you some kind of ferret?”

“I’m a cat. I’m not from around here. My name is Anton.”

“Oh,” said the cub, leaning against his brother’s side. “We’re sort of cats, too, I think. Lynxes, Momma says.”

Gotcha looked on, clearly pleased with himself. “I’m Mr. Gotcha,” he said. “You tell your momma it was me and Mr. Anton here what watched over you while you was waitin’ on her.”

“We’ll tell her,” they said together. “She’ll be back soon.”

Gotcha gave Anton a look of mild alarm. “We best be goin’, right, Mr. Anton?”

Anton took the hint. “Right, Mr. Gotcha,” he said. “You kits be careful now.”

At that moment a ferocious scream rang out in the distance. Anton’s fur stood along his spine. In the cloudy moonlight he made out the figure of a creature, cat-like but three times as big as he was, topping a rocky rise and streaking toward them with alarming speed.

“Is that . . .?” Anton began.

“That’s the momma,” cried Gotcha. “Run, Mr. Anton!”

The pair sprang away from the cubs and raced across the clearing toward the tall grass beyond the stream. Anton had always thought of himself as a fast runner, but the momma lynx closed the distance in seconds. She snarled furiously, almost on top of them as they burst into the line of grass. Gotcha ran a few yards behind, and Anton heard the snap of jaws and a yip from the ferret as they scrambled blindly through the brush.

“Gotcha!” called Anton as he ran. “You okay?”

“Still here!” panted Gotcha from somewhere nearby. “But we ain’t gonna outrun her, Anton.”

“Head for the tracks!” yelled Anton, hoping that the human buildings and smells would turn the lynx away. They swerved and the train station loomed ahead, and at last the sounds of pursuit faded. The mother lynx had let them go. They stopped near some spindly shrubs, leaning to catch their breath.

“Whoo-ee, that was right close,” said Gotcha, examining his backside where the lynx had grazed him with her teeth.

“Too close,” said Anton, shaking his head, though the sight of the huge wild cat had been briefly thrilling.

“Never underestimate a momma,” said Gotcha. “My own was tough as nails, just like that, always protectin’ her kits.”

Anton nodded, thinking of Sonya far away across the land and sea, taking care of his little brothers and sisters. He wondered if she’d be surprised to hear that her sons had managed to lose each other in a strange world, once again.