IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting to know antes, the deal, and betting structure

Knowing when to hold or fold

Recognizing winning hands

Understanding the importance of live cards

Looking at Seven-Card Stud in depth

Seven-Card Stud is the most popular of all the stud games, and has been since it first appeared sometime around the Civil War. There are also six- and five-card variants, but they’re not nearly as popular as the seven-card version. With three down cards and four exposed cards in each player’s hand at the end of the hand, Seven-Card Stud combines some of the surprises of Draw Poker with a good deal of information that can be gleaned from four open cards.

Seven-Card Stud has five rounds of betting that can create some very large pots. Skilled Seven-Card Stud players need an alert mind and good powers of retention. A skillful player is able to relate each card in his hand, or visible in the hand of an opponent, to once-visible but now folded hands in order to estimate the likelihood of making his hand, as well as to estimate the likelihood that an opponent has made his.

In Seven-Card Stud almost every hand is possible. This is very different than a game like Texas Hold’em, in which a full house or four-of-a-kind isn’t possible unless the board contains paired cards, and a flush is impossible unless the board contains three cards of the same suit.

With nearly endless possibilities, Seven-Card Stud is a bit like a jigsaw puzzle. You must combine knowledge of exposed and folded cards with previous betting patterns to discern the likelihood of any one of a variety of hands that your opponent might be holding.

What to Do If You’ve Never Played Seven-Card Stud Poker

Seven-Card Stud requires patience. Because you’re dealt three cards right off the bat — before the first round of betting — it’s important that these cards are able to work together before you enter a pot. In fact, the most critically important decision you’ll make in a Seven-Card Stud game is whether to enter the pot on third street — the first round of betting.

Seven-Card Stud requires patience. Because you’re dealt three cards right off the bat — before the first round of betting — it’s important that these cards are able to work together before you enter a pot. In fact, the most critically important decision you’ll make in a Seven-Card Stud game is whether to enter the pot on third street — the first round of betting.

The next critical decision point is whether you should continue playing on the third round of betting, called fifth street. In fixed-limit betting games, such as $6–$12, fifth street is where the betting limits double. There’s an old adage in Seven-Card Stud: If you call on fifth street, you’ve bought a through-ticket to the river card (the last card).

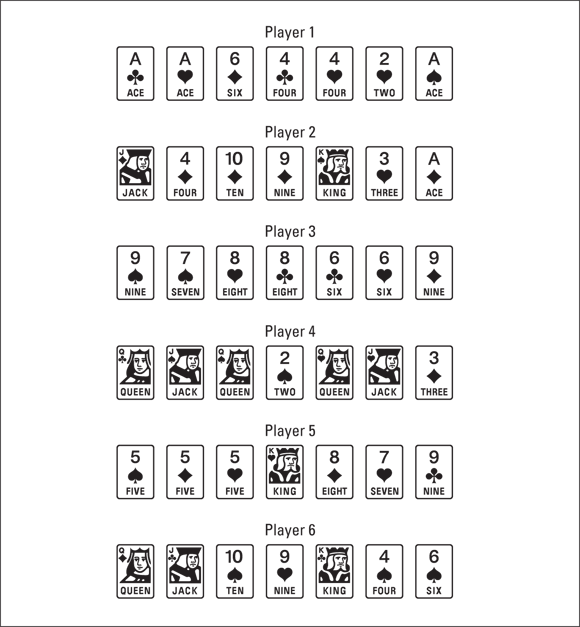

Figure 3-1 shows a typical hand of Seven-Card Stud after all the cards are dealt. The first three cards, beginning from the left, are considered to be on third street, the next single card is fourth street, and so on, until seventh street.

At the conclusion of the hand, when all the cards have been dealt, the results are as follows:

- Player 1 now has a full house, aces full of 4s. He is likely to raise.

- Player 2 has an ace-high diamond flush.

- Player 3, who began with a promising straight draw, has two pair — 9s and 8s.

- Player 4 has a full house, queens full of jacks, but will lose to Player 1’s bigger full house.

- Player 5 has three 5s, the same hand she began with.

- Player 6 has a king-high straight.

In Seven-Card Stud, each player makes the best five-card hand from his seven cards. The highest hand out of all the players wins. (In Figure 3-1, Player 1 takes the pot.)

Although most stud games don’t result in this many big hands contesting a pot, you can see how the best hand changes from one betting round to another, and how a player can make the hand he is hoping for, yet not have any chance of winning.

Seven-Card Stud requires a great deal of patience and alertness. Most of the time, you should discard your hand on third street because your cards either don’t offer much of an opportunity to win, or they may look promising but really aren’t because the cards you need are dead. (For details about dead cards, see the section titled “Comprehending the Importance of Live Cards” in this chapter.)

Seven-Card Stud requires a great deal of patience and alertness. Most of the time, you should discard your hand on third street because your cards either don’t offer much of an opportunity to win, or they may look promising but really aren’t because the cards you need are dead. (For details about dead cards, see the section titled “Comprehending the Importance of Live Cards” in this chapter.)

Antes, the Deal, and the Betting Structure, Oh My

Before the cards are dealt, each player posts an ante, which is a fraction of a bet. Each Poker game begins as a chase for the antes, so this money seeds the pot.

Players are then dealt two cards face down, along with one face up. The lowest exposed card is required to make a small bet of a predetermined denomination. This bet (and the person who makes this bet) is called the bring-in. If two or more players have an exposed card of the same rank, the determining factor is the alphabetical order of suits: clubs, diamonds, hearts, and spades.

Betting

The player to the immediate left of the bring-in has three options. He may fold his hand, call the bring-in, or raise to a full bet. In a $20–$40 game, the antes are usually $3 and the bring-in is $5. The player to the bring-in’s left can either fold, call the $5 bring-in bet, or raise to $20 — which constitutes a full bet.

If that player folds or calls the bring-in, the player to his immediate left has the same options. As soon as someone raises to a full bet, subsequent players must fold, call the full bet, or raise again.

Once betting has been equalized, a second card is dealt face-up, and another round of betting ensues. This time, however, it’s in increments of full bets. The player with the highest ranking board cards (cards that are face up) acts first.

If there are two high cards of the same suit, the order of the suit determines who acts first. The highest suit is spades, followed by hearts, then diamonds, and finally, clubs.

The first player to act may either check (a check, in actuality, is a bet of nothing) or bet. If a player has a pair showing (called an open pair), whether that pair resides in her hand or that of an opponent, she has the option to make a big bet in most cases. For example, in a $20–$40 game, the betting is still in increments of $20 on fourth street, except when there is an open pair. Then it’s the discretion of any bettor to open for either $20 or $40, with all bets and raises continuing in increments that are consistent with the bet. (If the first two cards dealt face up to Brenda in a $20–$40 Stud game were a pair of jacks, then she or anyone else involved in that hand can bet $40 instead of $20.) This rule allows someone with an open pair to protect her hand by making a larger wager.

Raising

Most casinos allow three or four raises per betting round, except when only two players contest the pot. In that case, there is no limit to the number of raises permitted.

In Stud, the order in which players act (called position) is determined by the cards showing on the board and can vary from round to round. With the exception of the first round of betting on third street, where the lowest ranked card is required to bring it in, the highest hand on board acts first and has the option of checking or betting.

The highest hand could range anywhere from four-of-a-kind, to trips (three-of- a-kind), to two pair, to a single pair, or even the highest card, if no exposed pair is present.

Double bets

Betting usually doubles on fifth street, except if there’s a player on fourth street who holds a pair. When there is, anyone involved in the hand has the option of making a double bet, and those players still contesting the pot are dealt another exposed card. Sixth street is the same. The last card, called seventh street or the river, is dealt face down. At the river, active players have a hand made up of three closed and four exposed cards. The player who acted first on sixth street acts first on seventh street too.

Showdown

If more than one player is active after all the betting has been equalized, players turn their hands face up, making the best five-card hand from the seven cards they are holding, and the best hand wins in a showdown (see Figure 3-1).

Spread-limit games

Many low-stakes Seven-Card Stud games use spread limits rather than fixed limits. Many casinos will spread $1–$3 or $1–$4 Seven-Card Stud games. These games are usually played without an ante. The low card is required to bring it in for $1, and all bets and raises can be in increments from $1–$4 — with the provision that all raises be at least the amount of the previous bet. If someone bets $2 you can raise $2, $3, or $4 — but not $1. If the original bettor had wagered $4, you can fold, call his $4 bet, or raise to $8.

Identifying Winning Hands

Winning Seven-Card Stud generally takes a fairly big hand (usually two pair, with jacks or queens as the big pair). In fact, if all the players in a seven-player game stayed around for the showdown, the winning hand would be two pair or better more than 97 percent of the time. Even two pair is no guarantee of winning, however, because 69 percent of the time the winning hand would be three-of-a-kind or better, and 54 percent of the time the winning hand would be at least a straight.

A straight is the median winning hand: Half the time the winning hand is a straight or better, half the time a lesser hand will win the pot.

If you plan to call on third street, you need a hand that has the possibility of improving to a fairly big hand.

Because straights and flushes are generally not made until sixth or seventh street, you should raise if you have a big pair (10s or higher). In fact, if someone else has raised before it’s your turn to act, go ahead and reraise — as long as your pair is bigger than his upcard. The goal of your raise is to cause drawing hands to fold so your big pair can win the pot — particularly if it improves to three-of-a-kind or two pair.

Because straights and flushes are generally not made until sixth or seventh street, you should raise if you have a big pair (10s or higher). In fact, if someone else has raised before it’s your turn to act, go ahead and reraise — as long as your pair is bigger than his upcard. The goal of your raise is to cause drawing hands to fold so your big pair can win the pot — particularly if it improves to three-of-a-kind or two pair.

Big pairs play better against a few opponents, while straights and flushes are hands that you’d like to play against four opponents (or more). It’s important to realize that straights and flushes start out as straight- and flush-draws. Draws are hands with no immediate value and won’t grow into full-fledged straights and flushes very often. But these draws have the potential of growing into very big hands, and those holding them want a lot of customers around to pay them off whenever they are fortunate enough to complete their draw.

Comprehending the Importance of Live Cards

Stud Poker is a game of live cards. If the cards you need to improve your hand are visible in the hands of your opponents or have been discarded by other players who have folded, then the cards you need are said to be dead. But if those cards aren’t visible, then your hand is live.

Many beginning Seven-Card Stud players are overjoyed to find a starting hand that contains three suited cards. But before you blithely call a bet on third street, look around and see how many cards of your suit are showing. If you don’t see any at all, you’re certainly entitled to jump for joy.

But if you see three or more of your suit cavorting in your opponents’ hands, then folding your hand and patiently waiting for a better opportunity may be the only logical course of action.

Even when the next card you’re dealt is the fourth of your suit and no other cards of your suit are exposed, the odds are still 1.12-to-1 against completing your flush. Of course, if you complete your flush, the pot will certainly return more than 1.12-to-1, so it pays to continue on with your draw. But remember: Even when you begin with four suited cards, you’ll make a flush only 47 percent of the time.

If you don’t make your flush on fifth street, the odds against making it increase to 1.9-to-1 — which means you’ll get lucky only 35 percent of the time. And if you miss your flush on sixth street, the odds against making your flush increase to 4.1-to-1. With only one more card to come, you can count on getting lucky about only 20 percent of the time.

This also holds true for straight draws. If your first four cards are 9-10-J-Q, there are four kings and an equal number of eights that will complete your straight. But if three kings and an eight have already been exposed, the odds against completing a straight are substantially higher and the deck is now stacked against you, and even the prettiest-looking hands have to be released.

The first three cards are critical

Starting standards are important in Seven-Card Stud, just as they are in any form of Poker. Those first three cards you’ve been dealt need to work together or contain a big pair to make it worthwhile for you to continue playing.

Position

Position (your place at the table and how it affects betting order) is important in every form of Poker, and betting last is a big advantage. But unlike games like Texas Hold’em and Omaha, where position is fixed for all betting rounds during the play of a hand, it can vary in stud. The lowest exposed card always acts first on the initial betting round, but the highest exposed hand acts first thereafter.

Because there’s no guarantee that the highest exposed hand on fourth street will be the highest hand on the subsequent round, the pecking order can very from one betting round to another.

Subsequent betting rounds

If you choose to continue beyond third street, your next key decision point occurs on fifth street — when the betting limits typically double. Most Seven-Card Stud experts can tell you that a call on fifth street often commits you to see the hand through to its conclusion. If you’re still active on fifth street, the pot is generally big enough that it pays to continue to the sometimes bitter end. In fact, even if you can only beat a bluff on the river, you should generally call if your opponent bets.

By learning to make good decisions on third and fifth street, you should be able to win regularly at most low-limit games.

Going Deeper into Seven-Card Stud

Seven-Card Stud is a game of contrasts. Start with a big pair, or a medium pair and a couple of high side cards, and you want to play against only a few opponents — which you can achieve by betting, raising, or reraising to chase out drawing hands.

If you begin with a flush or straight draw, you want plenty of opponents, and you’d like to make your hand as inexpensively as possibly. If you’re fortunate enough to catch a scare card or two, your opponent will have to acknowledge the possibility that you’ve already made your hand or are likely to make it at the earliest opportunity. If that’s the case, he may be wary of betting a big pair into what appears to be a powerhouse holding such as a straight or flush.

That’s the nature of Seven-Card Stud. The pairs do their betting early, trying to make it expensive for speculative drawing hands, and those playing draws are betting and raising later — if they’ve gotten lucky enough to complete their hands.

Starting hands

Most of the time you’ll throw your hand away on third street. Regardless of how eager you are to mix it up and win a pot or two, Seven-Card Stud is a game of patience. If you lack patience — or can’t learn it — this game will frustrate you to no end.

Many players lose money because they think it’s okay to play for another round or two and see what happens. Not only does this usually result in players bleeding their money away, the very fact that they entered a pot with less than a viable starting hand often causes them to become trapped and lose even more money.

Before making a commitment to play a hand, you need to be aware of the strength of your cards relative to those of your opponents, the exposed cards visible on the table, and the number of players to act after you do. After all, the more players who might act after you do, the more cautious you need to be.

Starting with three-of-a-kind

The best starting hand is three-of-a-kind, which is also called trips. But it’s a rare bird, and you can expect to be dealt trips only once in 425 times. If you play fairly long sessions, statistics show that you’ll be dealt trips every two days or so. Although it’s possible for you to be dealt a lower set of trips than your opponent, the odds against this are very long. If you are dealt trips, you can assume that you are in the lead.

You might win even if you don’t improve at all. Although you probably won’t make a flush or a straight if you start with three-of-a-kind, the odds against improving are only about 1.5-to-1. When you do improve, it’s probably going to be a full house or four-of-a-kind, and at that point you will be heavily favored to win the pot.

With trips, you will undoubtedly see the hand through to the river, unless it becomes obvious that you’re beaten. That, however, is a rarity.

Because you’ll be dealt trips once in a blue moon, it’s frustrating to raise, knock out all your opponents, and win only the antes. Because you are undoubtedly in the lead whenever you are dealt trips, you can afford to call and give your opponents a ray of hope on the next betting round.

The downside, of course, is that one of your opponents will catch precisely the card he needs to stay in the hunt and beat you with a straight or flush if you’re not lucky enough to improve. When you have trips, you’re hoping that one of your opponents will raise before it’s your turn to act. Then you can reraise, which should knock out most of the drawing hands.

Most of the time the pot is raised on third street, the player doing the raising either has a big pair or a more modest pair with a king or an ace for a side card. But your trips are far ahead of his hand. After all, he is raising to eliminate the drawing hands and hoping to make two pair in order to capture the pot. Little does he know that you’re already ahead of him, never mind the fact that you also have ample opportunity to improve.

Your opponent will probably call your reraise, and call you all the way to the river especially if he makes two pair. Here’s what usually happens. In the process of winning the pot, you earn three small bets on third street, another on fourth street, and double-sized bets on fifth, sixth, and seventh streets. If you’re playing $10–$20, you’ll show a profit of $100 plus the bring-in and the antes. If you’ve trapped an additional caller or two who wind up folding their hand on fifth street, your profit will exceed $150.

Big pairs

A big pair (10s or higher) is usually playable and generally warrants raising. Your goal in raising is to thin the field and make it too expensive for drawing hands to continue playing. A single high pair is favored against one opponent who has a straight or a flush draw. Against two or more draws, however, you are an underdog.

It’s always better to have a buried pair (both cards hidden) than to have one of the cards that comprise your pair hidden and the other exposed. There are a number of reasons for this. For one thing, it’s deceptive. If your opponent can’t see your pair — or even see part of it — it will be difficult for him to assess the strength of your hand.

It’s always better to have a buried pair (both cards hidden) than to have one of the cards that comprise your pair hidden and the other exposed. There are a number of reasons for this. For one thing, it’s deceptive. If your opponent can’t see your pair — or even see part of it — it will be difficult for him to assess the strength of your hand.

If fourth street were to pair your exposed card and you come out swinging, your opponent would be apprehensive about your having three-of-a-kind. This might constrain his aggressiveness and limit the amount you can win. But if your pair is buried, and fourth street gives you trips, no one has a clue about the strength of your hand, and they won’t until you’ve trapped them for a raise or two.

Big pairs play best against one or two opponents and can sometimes win without improvement. But you’re really hoping to make at least two pair. If you are up against one or two opponents, your two pair will probably be the winning hand.

Having said that, a word of caution is in order. It’s critically important not to take your pair against a bigger pair, unless you have live side cards that are bigger than your opponent’s probable pair. For example, if you were dealt J♦A♥/J♠, and your opponent’s door card is Q♠, her most likely hand is a pair of queens if she continues on in the hand. (The slash mark indicates that the two cards to the left of the slash were dealt to the player face-down. The card to the right of the slash was dealt face-up.)

Having said that, a word of caution is in order. It’s critically important not to take your pair against a bigger pair, unless you have live side cards that are bigger than your opponent’s probable pair. For example, if you were dealt J♦A♥/J♠, and your opponent’s door card is Q♠, her most likely hand is a pair of queens if she continues on in the hand. (The slash mark indicates that the two cards to the left of the slash were dealt to the player face-down. The card to the right of the slash was dealt face-up.)

As long as your ace is live, you can play against the opponent. For one thing, she might not have a pair of queens. She might have a pair of buried 9s, in which case you’re already in the lead. Even if she does have queens, you could catch an ace or another jack, or even a king. An ace gives you two pair that’s presumably bigger than your opponent’s hand, while trip jacks puts you firmly in the lead.

Even catching a live king on fourth street can help you. It offers another way to make two pair that is bigger than your opponent. You may be behind at this point, but you still have a number of ways to win.

Small or medium pairs

Whether you have a pair of deuces or a bigger pair is not nearly as important as whether your side cards are higher in rank than your opponent’s pair. If you hold big, live side cards along with a small pair, your chances of winning are really a function of pairing one of those side cards — and aces up beats queens up, regardless of the rank of your second pair.

Small or medium pairs usually find themselves swimming upstream and need to pair one of those big side cards to win. Although a single pair of aces or kings can win a hand of stud, particularly when it’s heads-up, winning with a pair of deuces — or any other small pair, for that matter — is just this side of miraculous; it doesn’t happen very often.

Playing a draw

If you’ve been dealt three cards of the same suit or three cards that are in sequence, the first order of business is to see if the cards you need are available. (Carefully check out your opponent’s exposed cards to see if any of the cards you need are already out.) If the cards you need are not already taken, you can usually go ahead and take another card off the deck.

If you see that your opponents have more than two of your suit or three of the cards that can make a straight, you really shouldn’t keep playing. If your cards are live and you can see another card inexpensively, however, go ahead and do so. You might get lucky and catch a fourth card of your suit, or you could pair one of your big cards and have a couple of ways to win. Your flush could get back on track if the fifth card is suited, or you could improve to three-of-a-kind or two big pair.

Drawing hands can be seductive because they offer the promise of improving to very large hands. Skilled players are not easily seduced, however, and are armed with the discipline required to know when to release a drawing hand and wait for a better opportunity to invest their money.

Drawing hands can be seductive because they offer the promise of improving to very large hands. Skilled players are not easily seduced, however, and are armed with the discipline required to know when to release a drawing hand and wait for a better opportunity to invest their money.

Beyond third street

Fourth street is fairly routine. You’re hoping your hand improves and that your opponents don’t catch the cards you need or a card that appears to better their own hand.

When an opponent pairs his exposed third street card, he may well have made three-of-a-kind. When this happens, and you have not appreciably improved, it’s usually a signal to release your hand.

Fifth street is the next major decision point. This is when betting limits typically double. If you pay for a card on fifth street, you’ll generally see the hand through until the river, unless it becomes obvious that you are beaten on board. It’s not uncommon for any number of players to call on third street and again on fourth. But when fifth street rolls around, there are usually only two or three players in the hand.

Often it’s the classic confrontation of a big pair — or two pair — against a straight or flush draw. Regardless of what kind of confrontation seems to be brewing, unless you have a big hand or big draw, you’ll probably throw away many of your once-promising hands on fifth street.

In fact, if you throw away too many hands on sixth street, you can be sure that you’re making a mistake on both fifth and sixth street.

If you are fortunate enough to make what you consider to be the best hand on sixth street, go ahead and bet — or raise if someone else has bet first. Remember, most players will see the hand through to the river once they call on fifth street. When you have a big hand, these later betting rounds are the time to bet or raise. After all, good hands don’t come around all that often. When you have one, you want to make as much money as you can.

If you are fortunate enough to make what you consider to be the best hand on sixth street, go ahead and bet — or raise if someone else has bet first. Remember, most players will see the hand through to the river once they call on fifth street. When you have a big hand, these later betting rounds are the time to bet or raise. After all, good hands don’t come around all that often. When you have one, you want to make as much money as you can.

When all the cards have been dealt

If you’ve seen the hand through to the river, you should consider calling any bet as long as you have a hand that can beat a bluff (assuming you’re heads up — playing against just one other player). Pots can get quite large in Seven-Card Stud. If your opponent was on a draw and missed, the only way for her to win the pot is to bluff and hope you throw away your hand. Your opponent doesn’t need to succeed at this too often to make the strategy correct. After all, she is risking only one bet to try to capture an entire pot full of bets.

Most of the time you’ll make a crying call (a call made by a person who is sure he will lose), and your opponent will show you a better hand. But every now and then, you’ll catch her speeding (bluffing), and you’ll win the pot. You don’t have to snap off a bluff all that often for it to be the play of choice.

Seven-Card Stud requires patience. Because you’re dealt three cards right off the bat — before the first round of betting — it’s important that these cards are able to work together before you enter a pot. In fact, the most critically important decision you’ll make in a Seven-Card Stud game is whether to enter the pot on third street — the first round of betting.

Seven-Card Stud requires patience. Because you’re dealt three cards right off the bat — before the first round of betting — it’s important that these cards are able to work together before you enter a pot. In fact, the most critically important decision you’ll make in a Seven-Card Stud game is whether to enter the pot on third street — the first round of betting. Seven-Card Stud requires a great deal of patience and alertness. Most of the time, you should discard your hand on third street because your cards either don’t offer much of an opportunity to win, or they may look promising but really aren’t because the cards you need are dead. (For details about dead cards, see the section titled “

Seven-Card Stud requires a great deal of patience and alertness. Most of the time, you should discard your hand on third street because your cards either don’t offer much of an opportunity to win, or they may look promising but really aren’t because the cards you need are dead. (For details about dead cards, see the section titled “ Having said that, a word of caution is in order. It’s critically important not to take your pair against a bigger pair, unless you have live side cards that are bigger than your opponent’s probable pair. For example, if you were dealt J♦A♥/J♠, and your opponent’s door card is Q♠, her most likely hand is a pair of queens if she continues on in the hand. (The slash mark indicates that the two cards to the left of the slash were dealt to the player face-down. The card to the right of the slash was dealt face-up.)

Having said that, a word of caution is in order. It’s critically important not to take your pair against a bigger pair, unless you have live side cards that are bigger than your opponent’s probable pair. For example, if you were dealt J♦A♥/J♠, and your opponent’s door card is Q♠, her most likely hand is a pair of queens if she continues on in the hand. (The slash mark indicates that the two cards to the left of the slash were dealt to the player face-down. The card to the right of the slash was dealt face-up.)