On the River Tigris in north Iraq

Capital of Assyria

Assur was situated on the upper Tigris, towards the southern end of its dependent territory, the land of Assyria, which, in good times at least, took in most of the north-east quarter of Mesopotamia. The list of its kings stretches as far back as those of any of the south Mesopotamian city-states, but the earliest rulers are noted to have ‘lived in tents’, and state and city had clearly not come together at this time (the end of the third millennium BC). The nomadic people of the region may have had Ashur as their god, but this Jehovah had still to find his Jerusalem. He seems to have done so shortly after, for an inscription from the city of Assur of c. 1950 BC describes work on temples for Ashur, Adad and Ishtar. Assur’s subsequent development was rapid. Within fifty years it had become a nodal point in the Near Eastern economy, facilitating the exchange of tin (from some source further east) for silver (obtained from Assyrian merchants resident in Anatolia).

This suggests that, from the start, Assur was a town with unusually strong commercial interests, and that such interests played an important part in shaping Assyrian policies. Annoyingly we have no way of confirming this. Assyrian annals are exclusively military, and exclusively victorious, so we have periods of triumph alternating with periods of silence, neither of them much help in determining what made the Assyrian state tick. It is perfectly possible that, with the ebbing of the special circumstances that had created the tin-for-silver trade, Assur sank back into a situation little different from that of any other Mesopotamian town, its main concern to defend its local interests, its main ambition to grab a slice of its neighbours’ territory or possessions. If such was the case it was reasonably successful: for 1,000 years it held its position in the Mesopotamian polity with only brief excursions up or down the ladder of fame.

The reign of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) marks a break in Assur’s typical history. The Assyrian state was transformed into a military machine. Warfare became continuous and the outlook imperial. Part of this programme was the building of a bigger, better capital. Assur wasn’t abandoned, it remained the religious centre of the kingdom, and under Shalmaneser III, Ashurnasirpal’s son and successor, it was even enlarged, but the energies of the state were now displayed elsewhere. Canterbury could not hope to rival London.

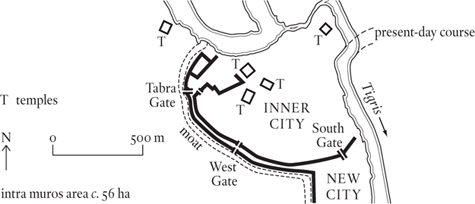

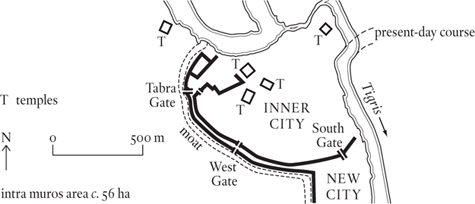

Assur occupied a tongue of land projecting into the Tigris, which curled around the northern and eastern sides of the city. Subsequently the river shifted away in the north, although it still flows alongside the east side of the site. The area within the original city walls was a bit under fifty hectares; the suburb added by Shalmaneser III brought this up to sixty hectares.

In its final state, Assur must have been an impressive place. The entire northern third was taken up by elaborate public buildings: two separate royal palaces, temples dedicated to Adad, Nebo and Sin, and a massive ziggurat and temple complex for Ashur. But the corollary to this is that not much space was left for people. To get the population up to 10,000 requires densities approaching 300 per hectare in the non-ceremonial space of the original city, and such figures seem improbable, to say the least. An urban population in the 5,000 to 7,500 range seems to be about as high as one could reasonably go.