Campania, Italy

Classical Beneventum (formerly Malies); capital of the late Roman province of Samnium

Under the name Malies, Benevento was the county town of the Hirpini, one of the four tribes that made up the Samnite confederacy of the south-central Apennines. It fell to the Romans in the course of the Samnite Wars – the wars that transformed ROME from a local into a peninsular power – and it was to cement this success that the Romans decided to turn Malies into a Latin stronghold. They didn’t like the name Malies – to them it sounded like Malventum (‘Evil Wind’) – so they renamed it Beneventum (‘Good Wind’). The new colony was established in 268 BC and shortly thereafter linked to the Roman road system by an extension of the Via Appia, the Rome–CAPUA highway. The subsequent extension of the Via Appia to Brindisi enhanced the importance of Benevento as a station on what soon became the main route to Rome’s rapidly expanding empire in the East.

Rome’s pacification programme in the Apennines was so successful that Benevento has little in the way of history. The colony remained faithful to Rome through the turbulent times provoked by Hannibal’s invasion of the peninsula in 218 BC, and through the upheavals of the Social War (91–87 BC), the final vehicle for the expression of Samnite discontents. In the early years of the second century AD, the emperor Trajan built a new road from Benevento to Brindisi on a better line than the one taken by the Via Appia (through Bari instead of TARANTO); he celebrated the completion of this ‘Via Traiana’ by building a triumphal arch at its starting point on the north side of town in AD 109. The arch survives in surprisingly good order, making Benevento vaut le voyage for those interested in things classical. The only other Roman construction to survive is a theatre built by Hadrian and enlarged by Caracalla.

The later history of Benevento is surprisingly upbeat. At the end of the third century it became the capital of Samnium, one of the new provinces set up by Diocletian as part of his administrative reform of Italy. In the late fifth century, when the western half of the empire dissolved, it became part of the Gothic kingdom of Italy; in the early sixth century it was recovered for the empire by Belisarius, commander of the East Roman expeditionary force dispatched by Justinian in 535. In 542, Totila, king of the Ostrogoths, retook the town and, to make sure it could not side against him again, slighted its walls. The collapse of Ostrogothic power in the 550s put it back in imperial hands again, but, not long after, it was seized by the leader of a Lombard war-band who in 571 made it the seat of an independent duchy. This confirmed its importance for the remainder of the Dark Ages, when it must have been one of the few Italian towns to retain a population at the same level it had sustained in the classical period – say 3,000 to 5,000.

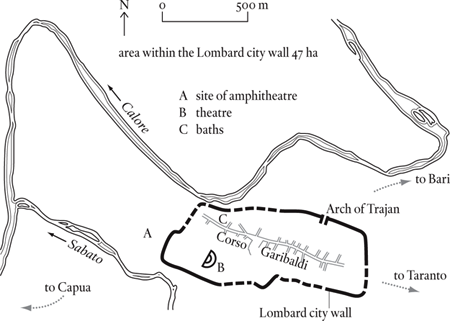

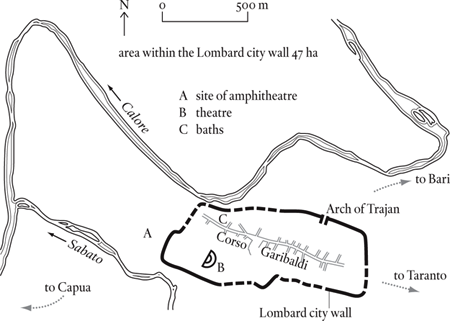

Little is known about the topography of Roman Benevento. It is generally assumed that the classical town walls underlie those of the Lombard period (which enclose an area of forty-seven hectares) and that the Corso Garibaldi follows the line of the Roman decumanus. The lie of the land and the distribution of the surviving Roman monuments – the Arch of Trajan on the line of the wall, the theatre within the line, and the amphitheatre outside – support this judgement.