Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Formerly Felsina; classical Bononia; a city of the eighth region of Italy, subsequently the province of Aemilia

Nowadays the easiest way to reach the plain of the Po from Tuscany is to take the road that runs due north from Florence to Bologna. In general terms this was equally true in antiquity, so when, in the late sixth century BC, the Etruscans began to establish a presence on the far side of the Apennines, Bologna was the natural place for them to start. Under the name Felsina it became the first – and always remained the foremost – of the Etruscans’ trans-Apennine colonies.

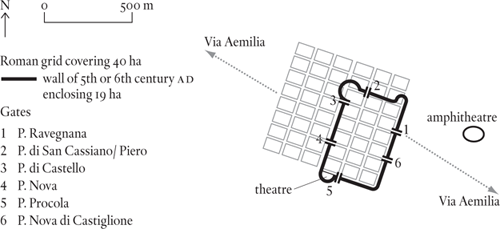

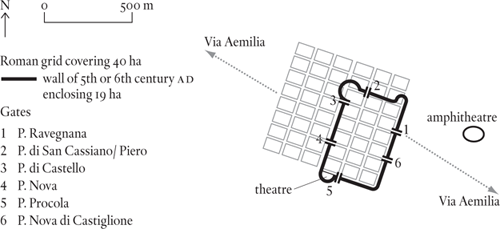

Felsina fell to the Celts, specifically to the Boii, in the mid fourth century BC, acquiring the name Bononia either then or when the Romans conquered the region in 196 BC. Its strategic position made it the obvious site for a Roman colony, and in 189 BC, 3,000 settlers were duly dispatched to set one up. Ignoring the existing settlement, the colonists laid out their city in the strictly rectangular form characteristic of de novo Roman foundations. In size it was at the upper end of the range for such places, its forty hectares being only a fraction less that PIACENZA’S forty-one hectares; the two of them were the only places of this calibre between the Apennines and the Po.

The towns in this valuable territory all lie along the arrow-straight Via Aemilia that runs from RIMINI on the Adriatic to Piacenza on the Po. The road, which eventually gave its name to the region (classical Aemilia, modern Emilia-Romagna) was built, or at least begun, in 187 BC, only a couple of years after the foundation of Bologna. The city already had its grid laid out by the time the Via Appia reached it, with the result that the road is kinked by its passage through the city. In fact it is this kink that provides the main clue to the layout of Bononia, which has otherwise left few convincing traces in the surviving street plan. That the reconstruction is correct is confirmed by the discovery of a theatre in an appropriate spot on the south side of the hypothetical grid. The position of the amphitheatre, of which nothing remains, is given by the title of a little church on the east side of town, S. Vitale e Agricola ‘in Arena’, but that is too far out of town to be equally helpful.

Bologna is rarely mentioned by Roman historians but seems to have survived well enough until the late imperial/early Lombard period, when the western half of the city was abandoned and a wall built enclosing only the eastern half (and not all of that), plus the theatre. In this reduced form, Bologna survived the Dark Ages, to emerge as a major player again in the high medieval period.

The first surviving population count is medieval: 8,000 hearths in 1371. This within a wall built between 1326 and 1370, enclosing 420 hectares, indicating a density at this time of 8,000 × 4.5/ 420 = 86 per hectare. Numbers had certainly been higher before the Black Death, and 100 per hectare would not be an unreasonable figure for the medieval period as a whole. Taking this as a guide, classical Bologna would have had a population of no more than 5,000 at its best, and no more than 2,000 in the Dark Ages.