Present-day Bad Deutsch-Altenburg (Carnuntum Fortress), Petronell (Carnuntum Town), Lower Austria

Capital of Upper Pannonia; diocese: Illyricum

Following the conquest of Pannonia by Augustus, units of the Roman army began to move up to the Danube line, which had now become the empire’s frontier in central Europe. In AD 15 the first legion to make the move, XV Apollinaris, pitched its camp at Carnuntum, forty kilometres (twenty-five miles) downstream from present-day Vienna. This fortification probably became the administrative centre for the new province of Pannonia, the northern half of what had previously been known as Illyricum.

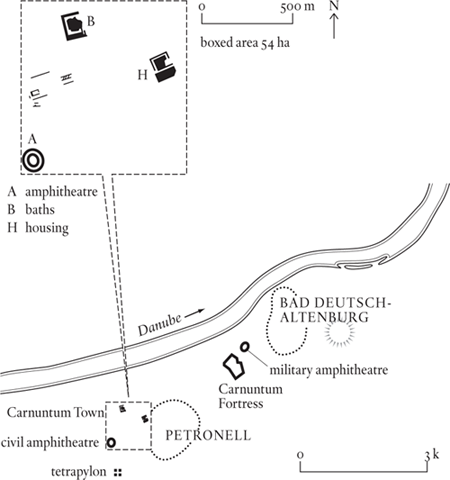

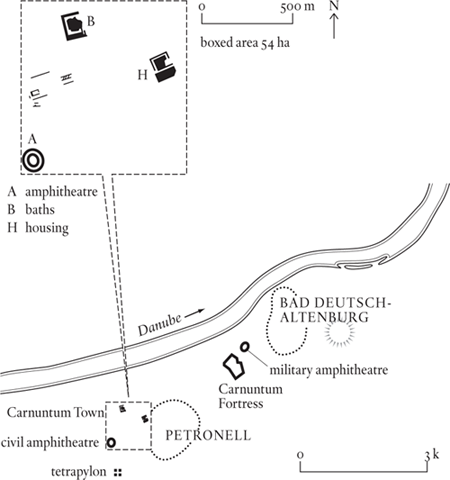

In AD 103 Trajan divided Pannonia into Superior and Inferior halves. From this point on, there is no doubt as to the status of Carnuntum: it was the capital of Pannonia Superior. This function was not served by Carnuntum Fortress, however, nor by the suburb that had grown up around it, but by a separate town constructed 2.5 kilometres (1.5 miles) to the west. This new settlement, which we can distinguish as Carnuntum Town, was recognized as a municipium by Hadrian (117–38) and as a colony by Septimius Severus (193–211).

By this time, the legions of the Upper Danube were beginning to find it increasingly difficult to uphold the Pax Romana. The emperor Marcus Aurelius had managed to defeat a first wave of Barbarians in the early 170s (years in which he was often resident at Carnuntum), but in the 250s many of the frontier fortresses were overwhelmed and much of Pannonia laid to waste. Eventually the frontier was restored and Carnuntum Town resumed normal life again. But it was no longer a provincial capital in the new administrative order introduced by Diocletian (285–305). He split Pannonia Superior into two halves, Pannonia Prima and Savia, and they had their capitals at SAVARIA and SISCIA, both well back from the frontier. Carnuntum Fortress was still manned by a legion (XIV Gemina, which had replaced XV Apollinaris in the early second century AD), but even legions were not what they had been, with probably no more than two cohorts. So in the early fourth century both Fortress and Town were past their best. Their decline was to continue as the century progressed, and in 375, when the emperor Valentinian II passed through Carnuntum, the Town was described as ‘quite deserted now, and in ruins’ (Ammianus Marcellinus, 30.5.2). The Fortress was still garrisoned, but by this time XIV Gemina would have been little more than a paper formation.

The topography of Carnuntum Fortress is distinct in that it was not only smaller than usual (sixteen hectares, compared to the eighteen to twenty hectares normal for a legionary base) but its plan was oddly skewed. However, it contains barracks for the full quota of ten cohorts, which suggests that its deviations from the norm are of little significance. More to the point is the scale of the surrounding cluster of buildings, considerably larger than most such suburbs. This could perhaps reflect an administrative role for the Fortress suburbs (canabae) before the building of Carnuntum Town.

The size and layout of Carnuntum Town are at present little known. With no part of the town wall discovered as yet, any figures must be speculative, but the uncovered remains are spread over an area of about fifty-four hectares, suggesting that the intramural figure was, at a minimum, about sixty hectares. If this is true, it was considerably bigger than its twin, AQUINCUM Town. That this is a real possibility is supported by the fact that the Carnuntum Town amphitheatre rivals the Carnuntum Fortress amphitheatre in size (the civil is 68 by 50 metres, the military 71 by 54 metres) whereas the Aquincum Town amphitheatre is notably smaller (the civil is 55 by 46 metres, the military 90 by 66 metres). Altogether it seems not unlikely that in its heyday, between AD 150 and 250, Carnuntum Town may have had a population of 5,000 or so.

South of the civil amphitheatre stand the ruins of a massive tetrapylon known now as the Heidentor (‘Pagan Gate’). It is probably Constantinian, and therefore Christian, but no inscription has survived, and what it commemorated is unknown. It isn’t a road-spanning arch of the usual type, because it has a plinth for a statue at its centre; it must be either triumphal, celebrating some victorious but as yet unidentified campaign, or funereal, honouring one of the less important members of the Constantinian dynasty.