Cyrenaica, Libya

The leading city of Cyrenaica from its foundation in the late seventh century BC to the mid third century AD; diocese: Egypt

Cyrene is a textbook example of colonization as a response to population pressure. The Aegean island of Thera (modern Santorini) has strictly limited resources: with the rise in numbers that occurred throughout the Greek world in the eighth and seventh centuries BC, the islanders’ future looked increasingly grim. Sometime in the late seventh century – the traditional date is 631 BC – the Therans dispatched an expedition to the stretch of the North African coast due south of Greece and settled some of their surplus citizens on an offshore island named Plataea. Conditions there proved to be no better than at home, but the native Libyans were friendly and showed the newcomers an inland site that seemed more promising. The position finally chosen by the settlers, some thirteen kilometres (eight miles) from the coast, was determined by the presence of an abundant spring. This spring, the locus of the water nymph Kura, gave its name to the city the Therans founded on the site and, from the city of Kurene, conventionally Latinized as Cyrene, the surrounding territory acquired the name of Cyrenaica.

By the time the Romans took over the area in 74 BC, Cyrene and Cyrenaica had a long history behind them. The region had lost its political independence early on, first to the Persians and then to the Ptolemies, but a steady stream of Greek immigrants had sustained the Greek character of Cyrene and led to the foundation of three similar cities on the coast: Eusperides (renamed Berenice by the Ptolemies), Taucheira (similarly renamed Arsinoe) and PTOLEMAIS, the last being a Ptolemaic foundation. Add APOLLONIA, the port of Cyrene, which had become a city in its own right, and you have the five cities that gave Cyrenaica its alternative title of Libya Pentapolis.

The Ptolemies had administered Cyrenaica from Ptolemais; the Romans preferred Cyrene, giving it the title of metropolis and rejecting Ptolemais’ claims to precedence. Under their rule Cyrene prospered until the end of Trajan’s reign when there was a rising by the city’s Jewish community led by a local firebrand whose name is variously recorded as Lucas or Andreas. His success indicates that Cyrene’s Jewish population had increased to a significant level in the Ptolemaic and early Roman periods and that, conversely, its elimination in the course of the conflict (which lasted from AD 115 to 117) left Cyrene with serious gaps in its economy and demographics, and a lot of damaged buildings. Hadrian (117–38) did his best to get the city back on its feet, drafting in new settlers, including 3,000 veterans, although some of these may have been earmarked for a new foundation of his named Hadrianopolis, on the coast. He also made funds available for rebuilding the city’s major monuments. But the work went slowly, some of the repairs being still incomplete seventy years later, and it seems likely that Cyrene never again achieved the level of prosperity it had enjoyed before the revolt.

By the later third century, there are definite signs of a downturn. There is a report of a war with the tribes of the interior in 268 which required the attention of the prefect of Egypt. Perhaps reflecting continuing unrest, Diocletian made Cyrenaica a province in its own right in 297, under the name Libya Superior (previously it had been the junior half of the province of Cyrenaica and Crete). At that time, he installed the new provincial administration in Ptolemais. Clearly the goodwill of the Libyans, which had been fundamental to Cyrene’s well-being from its foundation, had been lost, and, as a result, what had been Cyrenaica’s largest city rapidly dwindled. Ammianus Marcellinus, writing towards the end of the fourth century, describes the site as deserted. He may have been overdoing it: archaeology suggests that in his day, and for some while after, it was garrisoned by an army unit that had turned the forum into a fortress, but as far as civic life is concerned, he was absolutely right – the story of Cyrene was over. In the Arab period it isn’t mentioned at all.

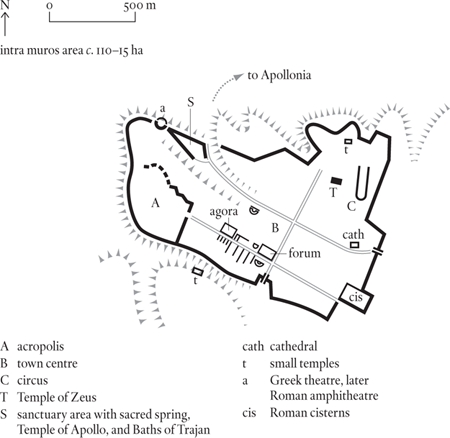

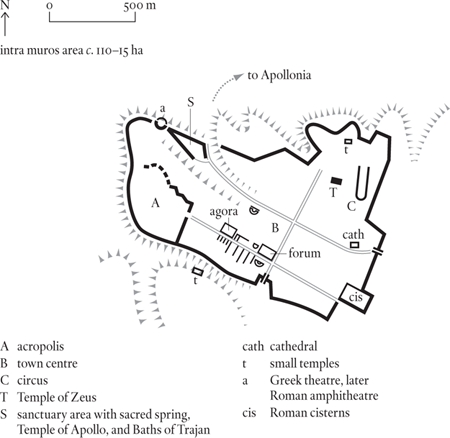

The ruins of Cyrene stand on the edge of an escarpment that overlooks the coastal plain. The town is divided by a wadi, which, as it ascends to the plateau, becomes the town’s main street. One third of the town’s area is north of this axis; the other two-thirds, the site of the earliest settlements and of the acropolis, lie to the south and west. The spring that had attracted the original settlers to the area is situated at an intermediate level, below the acropolis but above the mouth of the wadi; this triangular-shaped area was subsequently monumentalized with shrines and temples, fountains and baths. The main street lies under the present-day Arab village and its buildings are mostly hidden from view, but the parallel street to the south has been excavated. This was Cyrene’s civic centre, with the original Greek agora at one end and the Roman forum at the other. No fewer than four theatres have been found: a Roman one facing the forum, a smaller one (an odeon?) next to it, and a third facing the main street. The fourth, north-west of the sanctuary, was hollowed into the hillside in the Greek manner; the Romans converted it into an amphitheatre by building supporting arches on the downward slope. The north-eastern hill seems to have been reserved for the largest monuments: the Temple of Zeus, the circus and, in the late period, the city’s cathedral. The colossal columns of the Temple of Zeus were all thrown down in antiquity – by the Jews in the revolt of 115–17, according to current archaeological opinion, although the jumble (now reconstructed with original materials by an anastylosis) looks more like the work of an earthquake. The circus – as it dates back to Greek times we ought to call it a hippodrome – was a prominent feature, as might be expected given the Cyrenaicans’ prowess at chariot racing. They had a string of Olympic victories to their credit and many ancient authors comment on the excellence of the horses bred on the Cyrenaican plateau, and the skill of the drivers.

Cyrene’s population can only be a matter for speculation. With an intramural area of 110–15 hectares the town had room for 10,000 or more people, but that would be a very high figure for a colony at the margin of the Greek world; something like 5,000 is a more likely guess. A figure of this order could have been sustained throughout the city’s Hellenistic and early Roman history, say from 300 BC to AD 250, with the terminating date (the crash of the later third century AD) more established than the point at which the population first reached the 5,000 mark. The suggested date for this reflects the generally accepted supposition that the Greek economy moved up a gear at the start of the Hellenistic period.