Cherchell, 100 kilometres (62 miles) west of Algiers, Algeria

Capital of the Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis; diocese: Africa

Iol was founded in the sixth century BC as a trading post and naval station, part of the network of such places that the Phoenicians used to establish their grip on the south-western Mediterranean. By the end of the century it had been absorbed into the Carthaginian Empire; then, at the beginning of the second century BC, it was handed over by ROME to the kingdom of Numidia, its ally in the struggle against CARTHAGE. At this time, excavations suggest that the town covered eight to ten hectares, which in turn implies a population of no more than 1,000 or so.

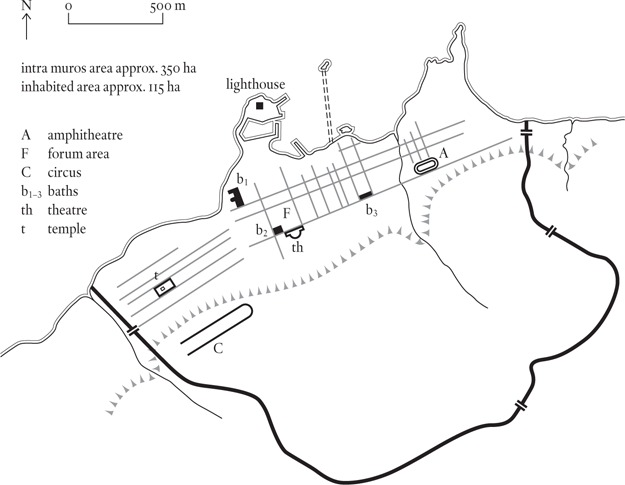

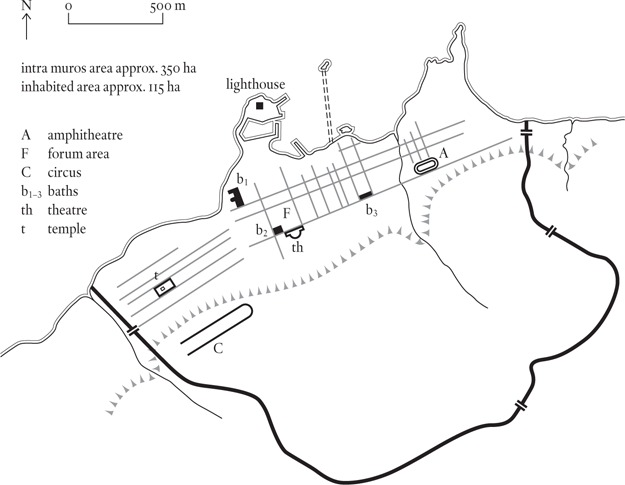

After quarrelling with Rome at the end of the century (in the Jugurthine War of 118–106 BC), Numidia lost Iol to its western neighbour, Mauretania. The town was looked on with favour by the Mauretanian kings and probably served one of them, Bocchus II (died 33 BC), as his capital. Briefly annexed by Rome on his death, the kingdom was revived for Juba II, a scion of the Numidian line, in 25 BC. Juba is remembered for two things: he married Cleopatra Selene, the daughter of Antony and Cleopatra, and he rebuilt Iol as a purely classical town, renamed Caesarea in honour of his patron, Augustus. Iol-Caesarea is in fact a twin of Herod the Great’s CAESAREA MARITIMA at the other end of the Mediterranean. Where Juba’s Caesarea differs from Herod’s is that although it was named in honour of the Roman emperor, it was not architecturally a Roman town; rather it reflected the passionate philhellenism of the king. A patron of Greek intellectuals, he was honoured as such at ATHENS. Juba undoubtedly used a Greek architect to lay out the new, much-enlarged version of Iol. The city wall snaked over the hills behind the town in typically Hellenistic fashion; the amphitheatre is a weird compromise between the standard Roman form and a Greek stadium. Incidentally, the currently accepted date for the wall is mid second century AD, but the picture it presents is so clearly Hellenistic that it is very difficult to agree with this. Perhaps it was refurbished during this period.

Juba was succeeded by his son Ptolemy, who died in AD 40. Shortly after this, the emperor Claudius decided to absorb the kingdom into the provincial system, making of it two provinces, Mauretania Tingitana in the west (capital, Tangier) and Mauretania Caesariensis in the east (capital, Caesarea). The Roman element in Iol-Caesarea was reinforced by a contingent of veterans, after which the city was officially titled Colonia Claudia Caesarea.

Classical authors have very little to say about Iol-Caesarea’s subsequent history, and archaeologists not much more. Hadrian gave the city a fine set of baths (b1 on the plan). Severus added a triumphal entrance to the circus. Economic activity seems to have reached a peak in the early third century AD; the fourth was an era of decline, with no new buildings, just modifications to existing ones. By the time the Vandals arrived in 429, the town was clearly in a poor way, and although the East Romans did succeed in recovering it in 534, they were unable to revive its fortunes. By the late sixth century the site was derelict.

As is so often the case with Greek circuits, the intramural area is an unreliable guide to Iol-Caesarea’s population; even the area between the hills and the shoreline – about a third of the total, say 115 hectares out of 350 – generates a suspiciously high figure, something in the region of 12,000 to 15,000. Perhaps 10,000 is allowable for the city’s best years, which cover the period AD 1 to 250.