Israel/Palestine

Jerusalem has the unenviable distinction of being a holy place in three different religions: it’s holy for the Jews who built it, for the Christians whose faith was born there, and for the Muslims for whom it is the setting of the Isra and Mi’raj, the Prophet’s magical overnight journeys from Mecca to the Temple Mount and from the Temple Mount to Paradise. As a result Jerusalem has had a lot of history – more at times than it might have chosen – but its frequent spells in the limelight don’t mean that it was ever a big place. In fact its usual position in the Near East’s urban hierarchy has been quite lowly.

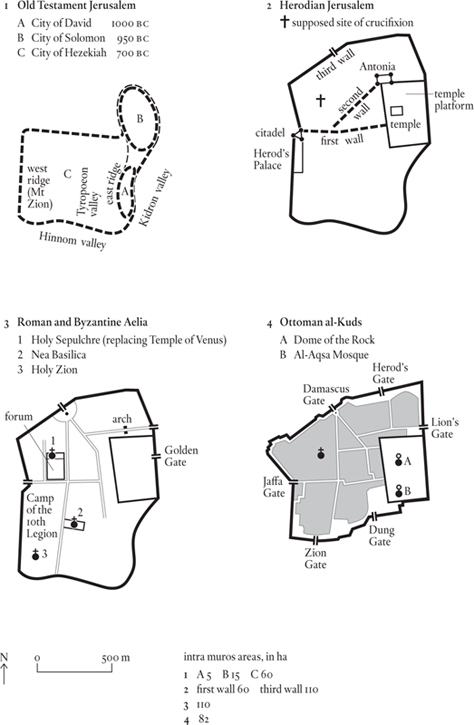

Jerusalem’s story begins around 1000 BC with King David’s capture of what had been, until then, a Canaanite village situated on a hilltop in the rolling, dusty landscape of Judaea. David built his palace there, and his son Solomon picked an area further north on the same ridge for the site of what is now termed the First Temple, a permanent dwelling place for the Jews’ hitherto peripatetic totemic deity, Jehovah. Between them, father and son had created a centre that could serve both the political and religious needs of the Jewish people. Alas, after Solomon’s death only two of the ten Hebrew tribes continued to recognize Jerusalem’s primacy. This meant that the town’s growth was slower than might have been anticipated, and it was not until 300 years later, in the reign of King Hezekiah (715–687), that it needed anything extensive in the way of a city wall. The immediate stimulus was probably in 722 BC, when the Assyrian king Sargon II conquered Samaria, the breakaway state founded by the ten northern tribes. Refugees from Samaria will have pushed up Jerusalem’s numbers, and the threat from Assyria will have encouraged Hezekiah to look to his capital’s defences. The result was Jerusalem’s most ambitious secular project yet, a defensive circuit that took in both the initial (east) ridge and the parallel ridge to the west (Mount Zion in current terminology).

Hezekiah’s wall served the city well, preserving it through the alarming years of Assyrian supremacy. But the kings of Judah were less successful when it came to dealing with the Assyrians’ successors, the Neo-Babylonians, and in 587 BC Nebuchadnezzar of BABYLON took Jerusalem by storm. The temple was destroyed, the walls razed, the inhabitants dispersed or deported, and the site left desolate. The first phase in Jerusalem’s history was over.

The second phase began half a century later in 539 BC with Babylon’s capture by the Persians. The Persian king Cyrus gave the exiled Jewish leadership permission to return home and begin the rebuilding of their shattered state. The better part of another century was to pass before the walls were rebuilt (under Nehemiah, c. 445 BC) and even then the scale was pretty paltry: the traces seem confined to the east ridge, meaning that the town was little, if any, bigger than it had been in Solomon’s day. But slowly population growth resumed and by the time the Persians were replaced by the Macedonians, and the Macedonians in their turn had begun to lose their grip, the city was back to the size it had attained under Hezekiah. This was the situation – a Jerusalem that was once again the comfortably populated capital of a fairly prosperous mini-state – when the Romans, in the form of Pompey and his legions, appeared on the scene.

Pompey made short work of the Jews’ political pretensions, taking Jerusalem by assault in 63 BC and drastically reducing the size of the Jewish state. What was left he entrusted to Antipater of Idumea, an Arab from the Negev who, after various vicissitudes, was succeeded in power by his son, Herod the Great. Nobody likes Herod much, but equally nobody questions his shrewdness. He was ruling a largely Jewish population at a time when Jewish fundamentalism was a growing force, in the name of a Roman emperor having little patience with people who rejected Rome’s ‘civilizing mission’. His solution to this dichotomy was to have two capitals: one, CAESARAEA MARITIMA, entirely Roman; one, Jerusalem, entirely Jewish. At both he was to build feverishly – indeed the idea may well have come to him because he enjoyed building so much – as well as at the various country palaces such as Masada and the Herodium which served as places of retreat (both socially and militarily). The major construction at Jerusalem was, of course, the Temple, its platform and the colonnades that surrounded it, a far more magnificent ensemble than the one it replaced. At the north-west corner of the platform he built a fortress, named the Antonia after one of his Roman patrons, Mark Antony. Running from the Antonia to the existing north wall of the city was a ‘Second [north] Wall’, which added a new quarter to the city, although we have little idea of its extent. On the opposite side of the city from the Temple, Herod built another fortress, the Citadel, with three immensely strong towers. To the south of the Citadel lay the royal palace. Augustus boasted that he had found Rome brick and left it marble; Herod could have said much the same as regards Jerusalem.

Herod’s work was completed by his grandson, Herod Agrippa, who extended the city still further to the north and replaced the Second Wall with a new ‘Third Wall’. With this addition the classical city reached its maximum extent, an intramural area of 110 hectares. Its population was presumably also at a new maximum: it was certainly increasingly turbulent and hostile to Roman rule. In AD 66 the First Jewish War broke out, with the city successfully repelling the attack of the Twelfth Legion which had marched down from Syria to sort out the troublemakers. It was a misleadingly good start to an impossible project. By AD 70 there were four legions encamped around the city, which was reduced sector by sector over the course of the next five months. As in Nebuchadnezzar’s day, Temple and walls were destroyed, and what was left of the population scattered. The Tenth Legion was left behind to garrison the ruins.

The next change in Jerusalem’s status is associated with another Jewish war, the Third, starting in AD 130. It is unclear whether the war was provoked by the emperor Hadrian’s decision to refound Jerusalem as a Roman colony or whether the emperor decided on the makeover out of exasperation at Jewish intransigence. Either way, the end result was the same: Jerusalem was renamed Aelia Capitolina (Aelia being Hadrian’s family name; Capitolina after Jupiter Capitolinus, the titular god of the Roman state); pagan temples replaced the long deserted synagogues; and Jews were no longer allowed to set foot in the town or live in its territory.

Aelia was not intended to occupy a prominent position in the roster of Palestinian towns; its colonial status simply reflects the need to provide the veterans discharged by the Tenth Legion with a local retirement home. It did, however, gain increasing prestige with the rise of Christianity. When, in the reign of Constantine the Great, Christianity became the officially sponsored religion of the empire, the town became an economic beneficiary too. Pilgrims began to visit, among them Constantine’s mother, the empress Helena, who in 326 was lucky enough to find the True Cross, only yards away from the True Tomb of Christ. Constantine immediately ordered the construction of a huge rotunda-cum-basilica covering both sites. This structure, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, bits of which are still standing today, was only one of a number of buildings funded by public or private donations. At a time when most of the towns in the empire were shrinking, Aelia enjoyed an Indian summer. Jews were allowed back in, at first only one day a year, later as residents.

In the early seventh century, Palestine was lost by the Romans, first to the Persians (temporarily, in 614–30), then to the armies of the Prophet Muhammed (more permanently, in 637). As Jerusalem features in the lore of Islam, the city continued to receive special treatment under the new regime, gaining two major buildings in the first century of Arab rule, the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosque. Both are on the Temple Platform that had lain bare since the sack of the city in AD 70, and which was the focus of interest for Islamic scholars. As a result there seems to have been little conflict between new and old religions, and the city was able to continue in its now-habitual role, a target for pilgrims but in other respects a provincial backwater. In fact Jerusalem always seems to have done poorly when Palestine was part of a major empire. It was off the main routes, and imperial administrations typically preferred to base themselves nearer the coast. In the Arab period Palestine was run from a new town at Ramla, halfway between Jerusalem and the sea.

Jerusalem continued in its modest existence until the latter part of the tenth century when, along with Palestine, it passed under the rule of the Fatimids of Egypt. Under threat from the Turks, the Fatimids refurbished the city wall, but despite this they lost it to them in 1078. They recovered it twenty years later, just as the Crusaders were closing in on the city. The next year the Crusaders took the place by storm, massacring all those unable to pay a ransom, and many of those who had. The Christian pilgrims who followed in the Crusaders’ wake found the city and its holy places in a sorry condition. Some consolation was obtained by turning the Dome of the Rock into a Temple of Our Lord, and the al-Aqsa mosque into a palace for the Crusader kings, and some new construction followed during the eighty-eight years that the city remained in Christian hands. Then, in 1187, the Muslim hero Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, retook the city and expelled its Christian population. Thirty-two years later, another Ayyubid sultan, doubtful of his ability to hold Jerusalem against a Christian counteroffensive, pulled down much of the city wall so that no one else could hold it either. Deprived of security, the population drifted away. For the rest of the medieval period Jerusalem was, for all its famous monuments, a very minor place indeed.

Jerusalem has been destroyed and rebuilt so many times that it is extremely difficult to recover the city’s earlier layouts. The first securely placed item is Herod’s Temple Platform, but that, and the approximate outline of the city wall on the eve of the catastrophe of AD 70 (i.e. including the Third Wall in the north) is about all we have for sure as regards the Herodian city. We know a little more about Aelia because we have significant remains of two major monuments, Constantine’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Justinian’s Nea Basilica, plus the Madaba map, a pictorial map of Palestine that contains a vignette of Jerusalem. This vignette clearly shows the main north–south street and a parallel street to the east, both with full-length colonnades. It also shows a semicircular plaza inside the north gate with an honorary column at its centre; this explains why the Arabs call the gate – the present-day Damascus Gate – the Bab al-Amud, or Gate of the Column. The city walls seem to have followed the Herodian trace.

By the Ayyubid period the south wall had been rebuilt on a new, shorter line. This gave the city the shape it has today, although the present walls are an almost entirely Ottoman construction (specifically of 1536–40, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent). They do not stray far from the Ayyubid course. As a result, the intramural area was reduced from 110 to 82 hectares, i.e. by 25 per cent. It would be interesting to know exactly when this contraction took place; the best bet is the Fatimid era, for the fortifications were certainly renewed then (in 1033 and again in 1063), after what was certainly a very long period of neglect.

The name Jerusalem (alternatively spelled Hierosolyma) served the city from its foundation by David to its refoundation as a Roman colony by Hadrian, a period of over 1,000 years. The name conferred by Hadrian, Aelia Capitolina, was soon shortened to Elia. This remained the official designation of the city for the next five centuries and, with the spelling Iliya, for the first three centuries of Arab rule. In the course of the tenth century the local Muslim population began referring to it as al-Kuds, meaning ‘[the town of] the Sanctuary’, the Sanctuary being the Temple Platform. This became, and remains today, the standard Islamic usage.

All the serious monuments of Jerusalem have multiple names too. This is inevitable given the different languages used by the different faiths, but has been compounded by the Arabic delight in synonyms, especially strong in the case of much-venerated objects, where there is a rule that the holier something is, the more names it deserves. The end result is that Herod’s Temple Platform is variously known as the Temple Mount, Mount Moriah, the Haram al-Sharif (‘Noble Sanctuary’), and the Bait al-Maqdes (‘Holy House’). The first Arab rulers called it al-Aqsa (‘the Furthest [of the three Holy Places]’), a name now reserved for the mosque at its southern end.

The first run of figures we have, a set of five early Ottoman counts, falls just outside our period. The first four of these counts are preserved in full and, if we apply a multiplier of four, yield the following population totals:

An incomplete register for 1592 indicates that by then the population had fallen to about 75 per cent of the 1562 total, i.e. to somewhere in the region of 7,500, completing a picture of rise and decline in the course of the sixteenth century that is mirrored in many other cities of the Ottoman Empire and can be accepted as genuine. The 1592 figure is consistent with the next reliable estimate, a figure of c. 8,750 in 1800.

What these data suggest is that early modern Jerusalem usually had a population a bit short of 10,000, and that in earlier periods it would have taken very special factors to push numbers to, let alone above, this level. There are really only three periods when such special factors were operating. The first is the Herodian era, when the city’s population was boosted by Herod the Great’s building programme and the city itself showed a dramatic increase in size (from 60 hectares to 110 hectares, or by 80 per cent). On this basis it seems reasonable to accept figures of 10,000 for AD 1 and something in the range of 10,000 to 15,000 for AD 50. The second is the early Christian era, when the Constantinian building programme and the start of pilgrim traffic will surely have set the previously half-derelict town on the road to recovery. Unfortunately, this boost coincides with hard times for the empire generally, and if the city doubled its population in the course of the fourth and fifth centuries AD it would have been doing very well indeed. That, on my reckoning, won’t have been enough to bring it up to the 10,000 mark, for its baseline population once the Tenth Legion had left can hardly have been more than 4,000. Crusader Jerusalem is difficult to assess. However, we have just one point on the graph to consider because the city was only in Christian hands from 1099 to 1187, and in 1100 it will hardly have had the time to recover from the slaughter that accompanied its capture the year before. Was the influx of Christians enough to push numbers up to 10,000 by 1150? It is a very dodgy proposition, but, as I’m perhaps too inclined to lean to more conservative figures, let’s be generous for once. No more than 10,000, though.

About the final medieval phase there can be little doubt. According to Rabbi Nachmanides, the thirteenth-century city contained 1,700 Muslims, 300 Christians and two Jews, of whom he was one, i.e. a total population of around 2,000. This will have slowly built up to the 3,750 recorded in the first Ottoman census some 300 years later.