England

Classical Londinium; provincial capital of Roman Britain

Caesar’s account of his raid into Britain (54 BC) and the record of the Claudian invasion (AD 43) make it clear that there was no pre-Roman settlement in the London area; for the disunited Celts the lower Thames was an inter-tribal boundary, not a highway. Rome’s military engineers took a different view. Within a few years of the start of the conquest of the province, they were using a crossing (whether ford, ferry or bridge is not certain) at a point within yards of present-day London Bridge, and had developed port facilities on both banks. A civil settlement grew on the north side, and by AD 60 London could be compared in size to the colonies and tribal centres on which the Romans were intending to base their administration.

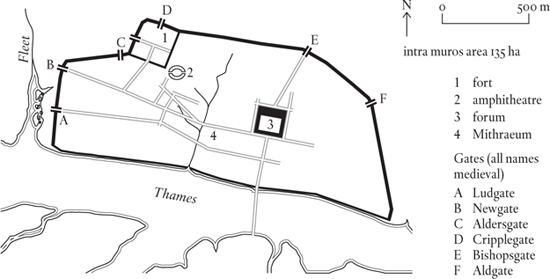

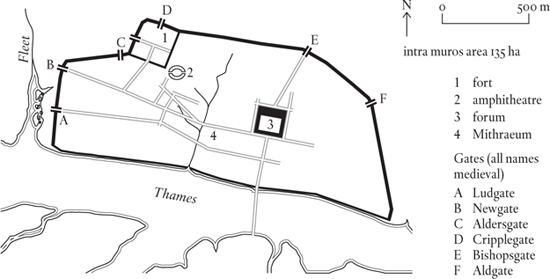

Romanization in general, and London in particular, suffered a sharp setback as a result of the revolt of Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, who burned down COLCHESTER, London and St Albans before her ultimate defeat in AD 60. London showed its vitality by making a quick recovery. By the end of the first century AD it had become easily the biggest place in Britain, and its practical advantages as a communications centre had led the governor of the province to make the city his official residence. Not much is known about the topography. It rather looks as though there was a formal settlement east of the Walbrook, and an unplanned one west of the brook, between the Cripplegate fort and the Thames. The formal settlement had a regular plan with a large forum and basilica complex as its centrepiece. This is the best known feature of Roman London, deservedly so as it was much the largest building in the province. The Cripplegate fort and its attached amphitheatre seem to have been constructed at much the same time as the official buildings east of the brook (in the late first century/early second century AD), which is a bit odd given the apparent lack of a single administration over the two settlements. Even more mysterious is the assumed bridge over the Thames, which everyone believes in, but for which there is not yet any clear evidence, and only eye-of-faith archaeology.

The city wall was built at the end of the second century AD, probably as part of the preparations made by Clodius Albinus, a governor of Britain who saw himself as a contender for the imperial throne, against the impending invasion of his more successful rival, Septimius Severus. A hundred years later – possibly at the time when another local man, Carausius, was trying something similar – the circuit was completed by the construction of a wall along the river front. The final Roman refurbishment of Londinium’s defences was carried out in the third quarter of the fourth century, when bastions were added to the land wall.

The surprising thing about the city wall is its extent. Archaeologists consider that Roman London was well past its best at the time the wall was built, and the built-up area, which even at its maximum fell far short of the 135 hectares enclosed by the wall, was contracting, not expanding. It seems that the scatter of buildings along the river, plus the presence of the Cripplegate fort, made a semicircle the most economical line to defend. As for the shrinkage in London’s population and pretensions, there is no doubt about that. The basilica had turned out to be a white elephant, and was to be demolished at the end of the third century; a triumphal arch built in earlier, more optimistic times was broken up and its stonework used in the construction of the river wall. London, like the other places on the provincial list it headed up, had failed to reach the Mediterranean-inspired targets set for it.

Eventually, in AD 410, the Romans withdrew their troops to meet more pressing needs elsewhere, and Britain reverted to the pre-conquest Celtic polity of tribal cantons. As such, it had no need of a capital, even so humble a one as late Roman London. Within fifty years of the departure of the last Roman soldier, the city was completely deserted.

What was Roman London’s population when the city was at its best, at the beginning of the second century AD? All we have to go on is the intramural area of 135 hectares, indicating a potential population, at 100 per hectare, of 13,500. Clearly actual numbers fell far short of this figure, but a peak population of 6,000 to 7,000 seems possible. This is enough to put it at the top of the demographically challenged roster of Romano-British towns, but not enough to enable it to qualify as a city in our numerically defined sense of a place with a minimum 10,000 inhabitants.