Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Classical Moguntiacum; capital of Upper Germany

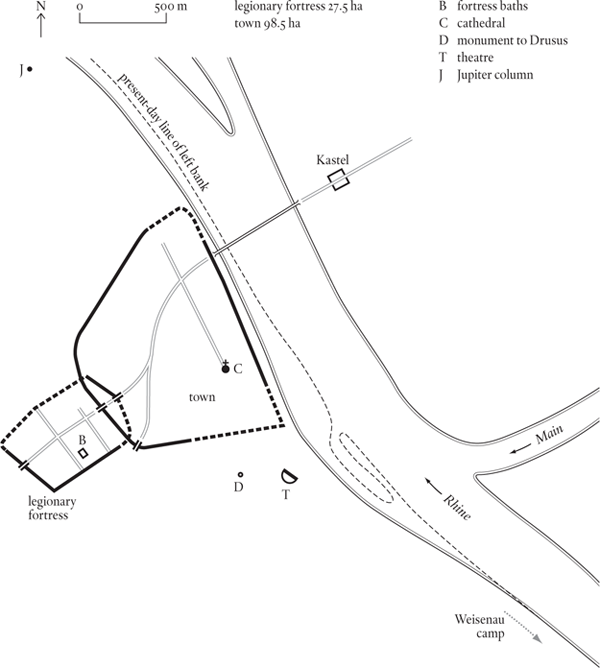

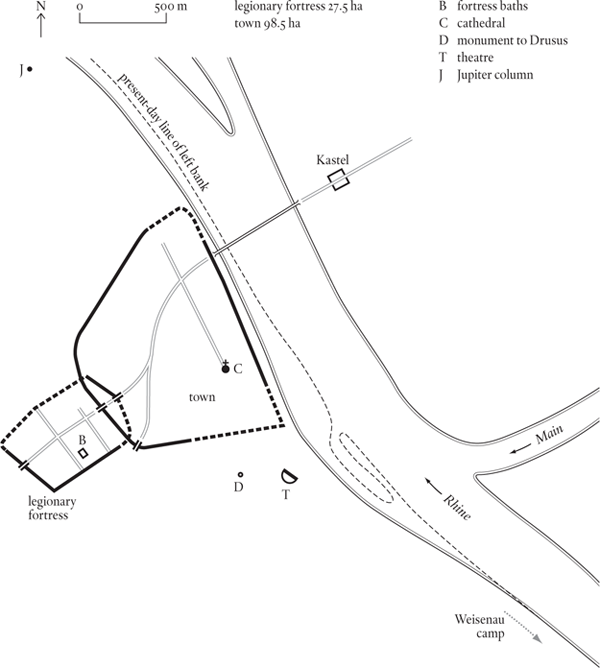

Moguntiacum was named for Mogon, a Celtic god who presumably had a sanctuary of some sort in the vicinity. What interested the Romans about the site was its geographical position, as it overlooks the Rhine just downstream from the point where the river is joined by the Main. This made Moguntiacum an obvious command-and-control centre for the upper Rhine, and Augustus posted two legions there as early as 13 BC. The legions set up their camp on a hill a bit back from the river. As the camp’s perimeter follows the contours of the hill, its plan is less regular than the general run of legionary fortresses. It covers twenty-eight hectares, a somewhat smaller area than one would have thought was needed for two legions, but then there was a satellite camp four kilometres (2.5 miles) upstream at present-day Weisenau. Some troops will also have been detached to man the fort at the head of the bridge across the Rhine. The bridge, of course, was the military establishment’s raison d’être, and its construction must have been one of the first tasks that the legions undertook.

As one of the empire’s biggest military bases, Mainz soon attracted a considerable civilian population. The whole left bank of the Rhine, from the harbour area a couple of kilometres downstream from the bridge, to an area opposite the junction with the Main a kilometre upstream, was dotted with the houses of traders and shopkeepers, and the shacks and lean-tos of less-respectable camp followers. The second century AD saw a theatre built at the southern end of this straggling town; there must already have been an amphitheatre somewhere, probably close to the legionary fortress, but it hasn’t been located as yet.

In AD 90 the garrison of Mainz was reduced from two legions to one, and Upper Germany became a civilian province (as opposed to a military command). This did not result in any loss of status for the town, where the provincial governor simply replaced the previous general in command – the two were anyhow not all that different in the Roman scheme of things. The only significant result was a shift in the centre of gravity from the legionary fortress on the Hochplateau to the as-yet-undefined town between the fortress and the river. Just how far this shift had gone by the third century is apparent in the drastic revision of the defences that took place after the near collapse of the empire in the 250s. All but the eastern end of the Hochplateau was abandoned, and a new wall built running in an arc from the river to the eastern end of the legionary fortress and then back to the river again. The focus was now entirely on the town, and whatever garrison remained was accommodated within the new circuit. This enclosed a tad under 100 hectares (assuming the missing corners have been filled in correctly), a very considerable area for this period, when the urban element was generally contracting rather than expanding.

The final century of Roman Mainz is ill-documented. The garrison was placed under the command of a ‘Dux Moguntiacum’, but he seems to have had very few troops at his disposal: neither in 368, when there was a serious German invasion, nor in 406, when a second incursion began the downfall of the Western Empire, did the town manage a successful defence. All that survived this debacle was the town’s ecclesiastical function, and Mainz soon joined the ranks of Dark Age ‘towns’ that consisted of nothing more than a few dozen poor dwellings clustered around a modest-sized cathedral. Things only began to pick up again in the ninth century AD.

Garrison towns – towns where the soldiers outnumber the civilians – aren’t real towns, so the idea that by AD 90 Mainz is likely to have had a population of around 15,000 (certainly 10,000 soldiers, and perhaps as many as 5,000 civilians) isn’t of much interest to the urban historian. But if, as is perfectly possible, Mainz hung on to the majority of its civilians after the reduction of the garrison to a single legion, the town would have acquired a viability that it hadn’t had before, and by the second century, with imperial prosperity at its peak, a half-military, half-civilian population of 10,000 would have given it a significant, if still slightly ambiguous, place in the urban hierarchy of the Gallic provinces. After AD 300 its relative position will have improved, even if absolute numbers fell. Decline will have accelerated with the rundown of the frontier defences that took place in the mid fourth century: by the mid fifth century, population is more likely to have been under than over the 1,000 mark.

Other than the (excellent) Landesmuseum Mainz and the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum there is not much to be seen of Roman Moguntiacum. There is the stump of a large monument to Drusus, Tiberius’ younger brother, and a replica of a Celtic ‘Jupiter-column’ put up in the wrong place. The other remains are foundations only. An interesting non-material survival is the name Kastel, still applied to the bridgehead suburb across the Rhine.