Italian Milano, Lombardy, Italy

Classical Mediolanum; capital of the late Roman province of Liguria, of the diocese of north Italy and, in the fourth century AD, of the West Roman Empire

The first settlement on the site of Milan is usually credited to the Etruscans, who in the course of the fifth century BC entered the Po valley and founded a dozen or so ‘cities’ there. One of these, Melpum, has traditionally been recognized as the forerunner of Milan. There is no real evidence for the identification, and if any form of Etruscan colony did exist where Milan stands today, it would have been swept away in the Celtic invasion of the early fourth century. The Celts who subsequently settled the area were the Insubres, and it was as their tribal capital, under the classical (but Celtic-derived) name of Mediolanum, that the town gets its first certain mention. This is only some thirty years before the Romans imposed their rule on the Insubres, which they did in 196 BC.

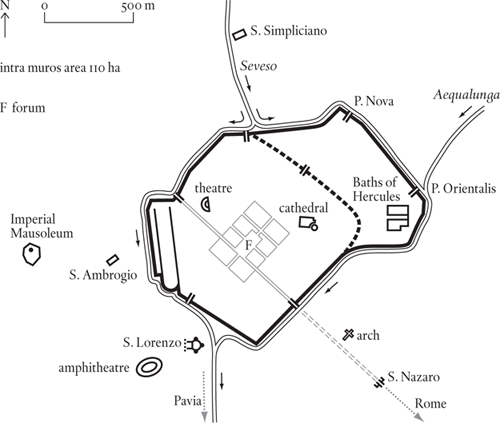

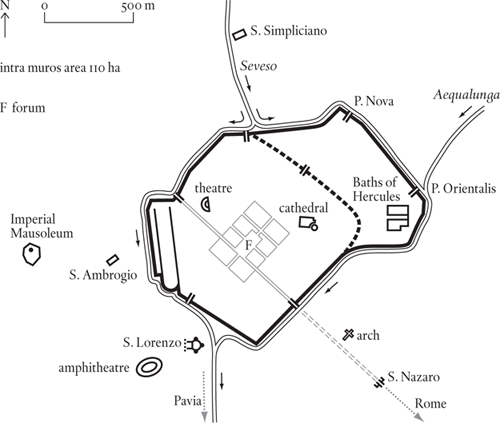

Subsequently, Milan grew in a slow and steady way until it emerged, some 500 years later, as the second city of Italy. The legal stages of its development are well known: Milan was officially deemed a Latin town in 89 BC and a Roman one in 49 BC; from being a municipality under the republic it became a colony under the empire. Unfortunately, far less is known about the city’s physical growth. At the heart of modern Milan there is a small area distinguished by a rectangular grid of streets. This suggests that at some stage the Romans laid out the city anew. The area involved was only eight hectares, which would indicate an early date (second century BC?) and a tiny population (1,000–1,500 ?). By the geographer Strabo’s day (around AD 1) the town had obviously grown a lot, for he puts it in the same category as VERONA. Strabo isn’t 100 per cent reliable about Italy, but we can accept the implication that Milan was now in the fifty-hectare class, because the few topographical clues that we have point in that direction.

The next phase, during which Milan outstripped all its rivals in north Italy, is associated with Diocletian’s reform of the imperial administration in the closing years of the third century AD. As far as Italy was concerned, this involved a demotion, for the peninsula lost its special status and was split up into smaller provinces like those in the rest of the empire. Milan, as the largest city in the new province of Liguria, automatically became the seat of the provincial governor. In fact, the neighbouring province of Aemilia was usually lumped together with Liguria, and the governor of Liguria was made responsible for both regions, having larger responsibilities than most of his colleagues. But this enhanced local status was only one element, and a minor one at that, in Milan’s promotion. Diocletian had decided to divide the empire into eastern and western halves, and the colleague he chose to rule the west, Maximian, established his court at Milan.

Maximian brought with him a large retinue, including, on the civilian side, the officials responsible for the next administrative tiers, the prefecture of Italy and the diocese of north Italy. To house them, he embarked on a major building programme, the result of which was the addition of new quarters on both the western and eastern sides of the city. The western side contained a palace and a circus: on the east there was a luxurious set of baths, the ‘Baths of Hercules’ – Maximian identified himself with Hercules just as Diocletian did with Jove. Milan also became the seat of an imperial mint. As befitted its enhanced size and status, the city was given a new set of walls, enclosing a total of 110 hectares. Ausonius describes these walls as ‘doubled’, which has been interpreted to mean parallel sets of fortifications like the land walls of CONSTANTINOPLE, but there is no sign of any such doubling in the surviving remains and it is possible that all Ausonius meant is that there were significant elements of an earlier circuit still standing in his day.

For the remainder of the fourth century, Milan continued to function as an imperial capital, although, as the number of emperors fluctuated between one and four at any one time, it didn’t always have a resident emperor. What it did have towards the end of the period was a remarkable bishop, St Ambrose, who ranks as one of the most important early church fathers. Ambrose arrived in Milan in a lay capacity, as governor of Liguria and Aemilia. He became the city’s bishop by public acclamation in 374 and subsequently emerged as the dominant figure in the Western church hierarchy. He is remembered today for his opposition to the Arian heresy, his introduction of chanting and hymn singing into the liturgy, and his excommunication of the emperor Theodosius I, who had permitted his troops to massacre the inhabitants of THESSALONIKI. His fame, however, has been somewhat overshadowed by that of his disciple, St Augustine, whom he baptized in the baptistry attached to St Tecla, the predecessor of the present-day Duomo, in 387.

St Ambrose died ten years later, as the storm clouds were gathering around the Western Empire. Five years after that, the generalissimo of the Western armies, Stilicho the Vandal, told the emperor Honorius that he couldn’t guarantee his safety if he remained in Milan. Honorius sensibly, if not very courageously, thereafter removed his court to RAVENNA. The predicted indignities were not long in coming. Northern Italy was overrun by the Visigoths a few years later, and Milan itself was sacked by Attila the Hun in 452. Major disaster, though, was postponed until the sixth century when the city was recovered for Rome by Justinian’s expeditionary force, only to be recaptured and subjected to a merciless sack by the Ostrogothic king Uraia in 539. According to the historian Procopius (c. 500–c. 562) in his account of the Gothic War, the city was reduced to ashes and its 300,000 male inhabitants slaughtered. As exaggerations go, this alleged death toll must be something of a record, probably being off by something like two orders of magnitude. It is unlikely that the city held more than 15,000 people for the Goths to put to the sword, and there are always some survivors of every massacre. But by the second half of the sixth century, Milan had certainly been reduced to a very low ebb. The Lombards, the final wave of Germans, who took the city in 569, thought so little of it that they chose neighbouring PAVIA – not previously a town in the same class as Milan – as their capital.

Aside from Procopius’ lunatic figure, we have no direct statement as to the population of Milan. However, his account (7.21) does make it clear that, despite the loss of the court, the city on the eve of the Ostrogothic sack was still the biggest in north Italy. If we allow 10,000 for Ravenna, this suggests a population of not much less than 15,000. At its peak in the fourth century it may have had a few thousand more. Ideas as to when Milan began to grow into a significant city remain speculative, but 5,000 in AD 1 is a believable starting point.