Present-day Balat, Aydin province, Aegean Turkey

Miletus was the most important place in Ionia during the eighth to sixth centuries BC, a period when Ionia – the central sector of Anatolia’s Aegean shore – was one of the key centres of the Greek world. It was the mother city of more than thirty colonies, most of them in the Black Sea (Milesian patriots later claimed that the real number was nearer ninety); it was also the focus of the ‘Ionian awakening’, the initiating phase of classical Greek civilization, and, in the political sphere, the leader of the Ionian revolt, the first in the long series of wars between Greeks and Persians.

Ionia was colonized by Greeks from the ATHENS region in the fifty years either side of 1000 BC. They founded a dozen ‘cities’ (meaning mini-states), two of them on the offshore islands of Chios and Samos, the rest of them on the corresponding stretch of the mainland. Miletus, the southernmost Ionian settlement, was the only one with a significant previous history, having been an outpost of the island culture of the Aegean in the Bronze Age. But the settlements of that era were tiny: the story of Miletus as an urban centre begins with the Iron Age Ionian community.

Miletus town was built on a peninsula that jutted into the Gulf of Latmos. A hill at its root, present-day Kalabaktepe, served as an acropolis; a wall extending from this defended the peninsula. These defences proved sufficient to ward off a series of invasions by the Lydian king Alyattes at the beginning of the sixth century BC, but subsequently the Milesians succumbed to Lydian pressure, and by the time of King Croesus they had become tributaries of the Lydian state. When Croesus was overthrown by Cyrus, the king of Persia, Miletus was automatically incorporated in the Persian Empire (546 BC). The terms were not harsh and Miletus gained a place in Persian councils.

At first the relationship seemed to work well. Miletus demonstrated its loyalty by faithfully guarding the bridge of boats built across the Danube by King Darius I for his Scythian campaign of 513 BC. This was a significant contribution because the campaign was a failure, and if the Ionians had burned the bridge – as some of them wanted to – Darius’ forces would have been in serious trouble. Yet barely fourteen years later, Miletus was to raise an Ionian revolt in an attempt to throw off Persian control. The rebellion was hastily conceived, ill thought out and ultimately doomed. Persian forces closed in on Miletus in 494 BC, broke through the city’s defences and razed it. For fifteen years the site lay deserted; then the Greek counteroffensive spearheaded by Sparta and Athens liberated Ionia, and such Milesians as survived began the long task of rebuilding their city. A second Persian occupation (404–334 BC) must have delayed the work, which only really got going after Miletus’ final liberation by Alexander the Great.

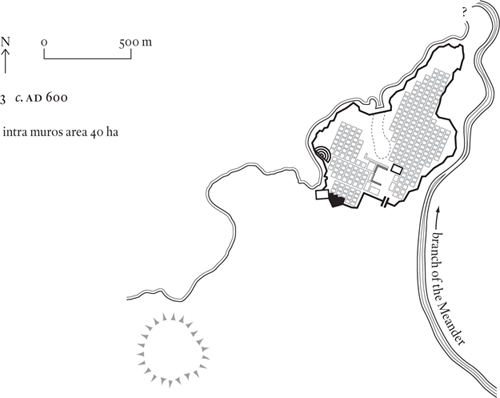

The revived Miletus grew into a reasonably prosperous place. It never regained its position at the top of the roster of Ionian cities, but it eventually reappeared as number three, after EPHESUS and SMYRNA. In Roman times it retained enough importance to be made the provincial capital of Caria when the original province of Asia was subdivided c. AD 300. But this was the city’s last bit of good news, for the fourth century was to mark the beginning of a severe decline. This had two components, of which the first was the Mediterranean-wide economic contraction that set in at this time. The second, specific to Miletus, was the silting up of its ports, as the Meander gradually filled in the Gulf of Latmos. In AD 343 the vicar of Asia supervised the construction of a canal that had apparently become necessary for continuing access to the sea. It couldn’t solve the long-term problem; by the sixth century the Lion Harbour had been abandoned and a new city wall was built straight across its mouth. This wall, traditionally ascribed to Justinian, protected only the upper town, reducing the intramural area from more than ninety hectares to barely forty. It seems likely that the next century saw a complete collapse in the city’s population, although some would argue for a gentler decline. All we know for sure is that by the tenth century AD the only remaining habitation was a castle built on the ruins of the Roman theatre. Here the Byzantine governor of the region had his ‘palace’, the word for which led the site to be named Balat. In village form Balat survived until 1955 when it was wrecked in an earthquake; the villagers then decided – much to the relief of the archaeologists – to rebuild on a new site, some distance away from the remains of the classical city.

The few data known for archaic (pre-494 BC) Miletus can be simply stated. There was a fortified acropolis on present-day Kalabaktepe and there were settled areas on the peninsula around the temples of Athena and Apollo. And that’s about it. The line of the city wall is unknown, apart from a partially excavated ring wall around the top of Kalabaktepe and a spur from this leading off towards the east side of the peninsula. If this wall took the course suggested in plan 1 below, the town would have had an intramural area of about 120 hectares.

Considerably more is known about classical Miletus. This is largely because it was built to an overall plan prepared by one of the city’s most famous sons, Hippodamus, the ‘father of town planning’. Hippodamus’ name immediately conjures up a picture of a regular street plan, with housing arranged in rectangular blocks, and Miletus certainly shows this. However, this was only part of his system, which also involved a clear segregation between public and private areas. At Miletus, the public zone lies across the centre of the peninsula, the trademark grids (on slightly differing orientations and patterns) occupying the areas to north and south.

Classical Miletus was smaller than its archaic predecessor. Any reoccupation of Kalabaktepe was short-lived, and the new city wall took a simple line across the base of the peninsula. This reduced the intramural area to some ninety to ninety-five hectares. Aside from the temples inherited from the archaic town, the public buildings included a theatre, a huge agora and a stadium. The Romans greatly enlarged the theatre, remodelled the stadium and built several sets of baths (one donated by Faustina, the wife of Marcus Aurelius). They also built a huge monumental gateway to the agora, which German archaeologists moved to Berlin in 1908; it can be seen in the somewhat confusingly named Pergamon Museum. Several churches and an episcopal palace survive from the period of the later empire.

There are no ancient figures on which to base a population estimate for Miletus town; the best we can do is to make an informed guess at the population of the Milesian city state. This can be done in two ways: first by using the number of ships that they manned at the Battle of Lade in 494 BC; secondly by attempting to calculate the ‘carrying capacity’ of the Milesian chora (countryside). The Battle of Lade represents an all-out effort by a Miletus that was fighting for its life, just as Salamis represents a similar all-out effort on the part of a cornered Athens. The Athenians, with a citizen body of 30,000 adult males, managed to equip 180 ships, the Milesians 80, suggesting that the number of adult male Milesians was about 30,000 × 80/180 = 13,333, and, using a multiplier of four, that the total population of Miletus state would have been around 50,000 to 55,000. This is considerably more than the ‘carrying capacity’ calculations, which fall in the range 23,000 to 34,000. Either way, archaic Miletus was clearly a large polity by the standards of the Aegean world at the time. This solves the main question raised by the colonization programme of the seventh and sixth centuries BC: did Miletus have the numbers to sustain this on its own? Given that only a few hundred settlers were needed to start a colony, the answer is clearly a yes. Even a population at the lower end of the suggested range would be enough to do it.

As to Milesian city proper, all one can say is that on the eve of its destruction in 494 BC it may have housed about 5,000 people. It is unlikely to have had many more because Athens, undeniably the Greek number one at the time, had fewer than 10,000. Recovery from the Persian sack was undoubtably slow, and numbers are unlikely to have reached the 5,000 mark again before the Hellenistic era. In late Hellenistic/early Roman times, the archaeological record shows that the city was adding to its amenities, and it is reasonable to believe that population reached a new peak in the second century AD, the heyday of the classical world. What this peak was is a matter of personal judgement. I would propose a figure of 7,000 to 8,000, while recognizing that there was room for twice that number within the walls. On any view the contraction that then set in will have taken numbers down to 5,000 again by the early sixth century when the intramural area was reduced to forty hectares.