Italian Padova, Veneto, Italy

Classical Patavium; a city in the tenth region of Italy, subsequently the province of Venetia et Histria

Padua, the county town of the Venetic Patavi, is first mentioned in 302 BC when the Spartan condottiere Cleomenes sailed up the Po estuary looking for some easy pickings. The Patavi soon showed that they were well capable of looking after themselves, and after suffering more damage than he had inflicted, Cleomenes withdrew in some haste. The Gauls’ entry into north Italy proved more of a problem; it was the need for a counter to their pressure that led the Patavi to form an alliance with the Romans. The Patavi were to remain faithful to this alliance even in the darkest days of the Hannibalic war.

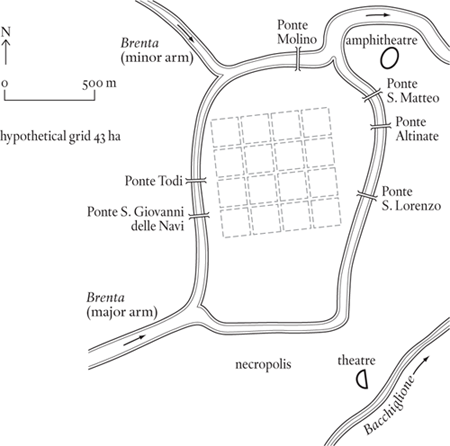

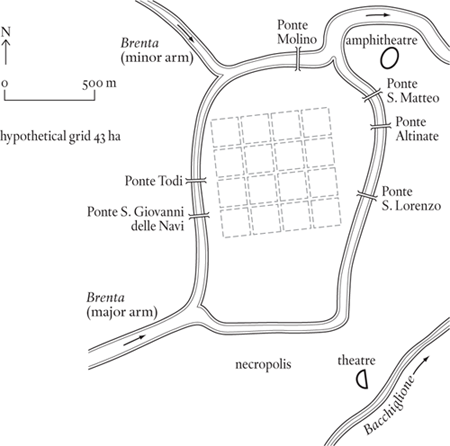

Friendship with ROME, as ever, led to absorption in the Roman sphere, and to the reconstruction, probably in the first century BC, of Padua as a Roman town. It quickly became very prosperous: the geographer Strabo brackets it with VERONA as one of the two most important places in Transpadana after MILAN. And although we know very little about Roman Padua, what we do know matches Verona’s topography to an extraordinary degree. Both were situated within a loop of river (the Adige in Verona’s case, the Brenta in Padua’s); both had an amphitheatre and a theatre at opposite ends of town, outside the formally planned area. As to the street grid itself, we can’t say too much because at Padua, unlike Verona, no trace of it remains today, and although something can be hazarded as to its siting and scale (on the basis of the surviving set of Roman bridges, the spacing of which presumably corresponds to the spacing of the main streets), it has to be admitted that the reconstructed plan is a fairly fanciful exercise. Nonetheless, there is only a limited amount of space within the Brenta loop (113 hectares to be exact) and it is not easy to fit in a square of much more than the suggested forty-three hectares. This is much the same as Verona’s forty-one hectares.

Where Padua and Verona part company is in their later history: Verona becomes more important, whereas Padua seems to have faded. It survived as a place of some significance, however, until 601, when it was subjected to a brutal sack by the Lombards and was abandoned by such of its inhabitants as survived. They re-established themselves on the far side of the Venetian lagoon, at Malamocco, where they were out of reach of any mainland enemy.

To judge by the chaotic jumble of streets at the heart of medieval Padua, it owed nothing to its Roman predecessors except for the six little bridges shown on the plan. But once refounded it grew rapidly, and by the thirteenth century had become one of the most prosperous places in the Lombard plain. In 1254 the number of adult males taking an oath of allegiance was recorded at 2,606, equivalent to a total population of about 11,000. Of these, about half lived within the loop as defined by a wall enclosing seventy-six hectares. The implied density of 5,500/76 = 72 per hectare suggests a population for Roman Padua of 3,000 to 4,000, although it may have touched 5,000 at its most prosperous in the first century AD.