Present-day Bergama, Izmir province, Aegean Turkey

Capital of the Roman province of Asia

In the days when Asia Minor was part of the Persian Empire, Pergamum was the seat of the Gongylides, a dynasty of expatriate Greeks that ruled the Caicus valley on behalf of Alexander the Great (336–323 BC). At this time, Pergamum was no more than a hilltop fortress with a small settlement attached to its southern side, and it was in this form that it submitted to the great king. Subsequently it became part of the territory held by Lysimachus, one of the generals who carved out kingdoms for themselves in the decades following Alexander’s death. In 282 BC, on his way to confront Seleucus, the most important of his rivals, Lysimachus parked his war chest in Pergamum, to be watched over by a trusted lieutenant, Philetaerus of Tieium. When Lysimachus was killed in the subsequent battle, Philetaerus found himself sitting on 9,000 talents that had no obvious owner, in the middle of a fortress that had no obvious master other than himself.

Philetaerus played his hand cautiously and cleverly, acknowledging Seleucus’ overlordship on the understanding that nothing much was done to implement it. When he died, in 263 BC, he was able to leave what was in effect a little kingdom to his nephew Eumenes, whom he had adopted as a son. Officially, however, it is the next ruler, Attalus I (241–197 BC), who is credited with founding the dynasty, as he was the first to use the title of king. He had three successors, Eumenes II, Attalus II and Attalus III, the last of whom died in 133 BC.

The most important of the Attalids was Eumenes II, who transformed his mini-kingdom into a middle-ranking state – at least as regards territory – by choosing exactly the right moment to become a friend and ally of the Roman people. In 190 BC the Romans expelled the Seleucids from Anatolia; they did not, however, want to rule it themselves, so they gave nearly all the land that the Seleucids had claimed there – roughly the west and south-west of the country – to Eumenes. This made him very rich indeed, but it had its downside, for what ROME had given Rome could take away; the kingdom of Pergamum might be a lot bigger, but it was also a lot less independent. Eventually the business of staying on the right side of Rome proved too much for the royal nerves, and Attalus III decided to bequeath his state to the care of the Roman people. The kingdom was transformed into the Roman province of Asia, with Pergamum as its initial capital.

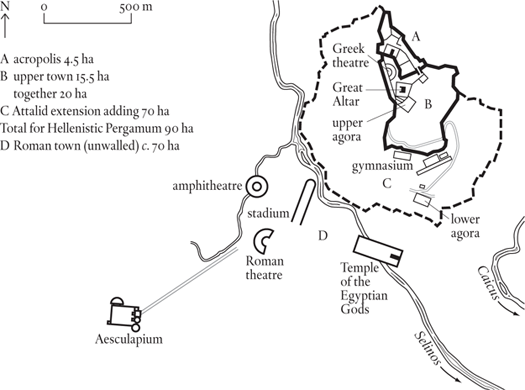

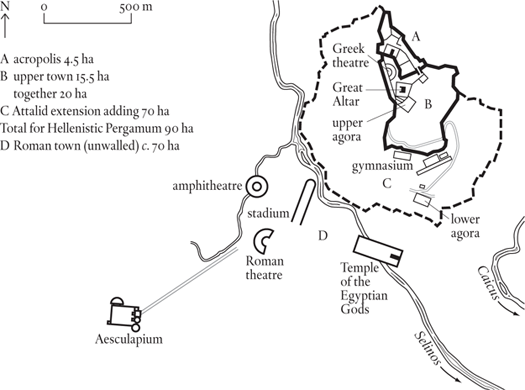

After a shaky start, the area settled down under Roman rule and the city of Pergamum was able to enjoy the benefits of the Pax Romana. Its capital status was soon lost – EPHESUS was much more convenient from the Roman point of view – but even when Augustus made the administrative transfer official in 28 BC, he allowed Pergamum to keep its seniority in matters ceremonial. Under Hadrian (AD 117–38) the city was the recipient of remarkable imperial favours. It was granted the title of metropolis, and if this was a somewhat meaningless use of the honorific – as part of the same deal Ephesus was promoted to ‘first metropolis’ – the building programme that the emperor initiated ensured that Pergamum kept its place among the leading cities of Asia. An entire new quarter was laid out at the foot of the hill, with the full range of amenities appropriate for a major Roman town: impressive temples, a huge forum, a theatre, an amphitheatre and a stadium. Nearly a kilometre (0.5 mile) outside the city limits a shrine to Aesculapius, the god of healing, was expanded into a lavish spa, which soon became a Mecca for wealthy Roman hypochondriacs.

Some of the prosperity created by these developments would not survive the downturn in imperial fortunes that marked the second half of the third century. In Pergamum’s case the empire’s ‘time of troubles’ was worsened by an earthquake in AD 262, and a sack at the hands of a marauding band of Goths. The arrival of Christianity also had negative impacts: the monuments of the old gods, of which Pergamum had a plethora, were no longer an asset; invalids ceased to come to the Aesculapion, and the site was abandoned. Nonetheless, urban life continued. In the mid fifth century the vast Temple of the Egyptian Gods was converted into a cathedral, a remodelling that looks as if it cost almost as much effort as the original building. Pergamum’s economy may have been damaged, but it clearly wasn’t defunct.

The end came in the early seventh century, with the Persian invasion that laid waste to so much of Anatolia. When the Persians were finally evicted, there seems to have been little left to restore, and the emperor Constans II (641–68) limited himself to refortifying the acropolis. For the next 500 years this tiny (ten-hectare) area was all there was to the once-proud city of the Attalids. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries there was a partial revival as refugees from the Turkish wars arrived in the area. Manuel Comnenus (1143–80) settled them in the Old Town immediately below the acropolis, cobbled together a defensive wall and declared this revived Pergamum the capital of the new theme of Neokastra. It seems to have been a spare settlement. The emperor Theodore Lascaris II (1254–8) commented bitterly on the contrast between the classical buildings and the ‘mouseholes’ in which the current generation of Pergamenes were living. The area passed to the Turks in the early fourteenth century – apparently without a fight – which meant that the hilltop town lost its purpose; such inhabitants as chose to remain relocated to the foot of the hill, among the ruins of the Roman town, where water was more readily accessible. This shanty town was to become the nucleus of Ottoman Bergama.

The original nucleus of Pergamum occupies the top of its hill, with an extension down the southern face, which has a relatively gentle slope. Even there the ground had to be terraced before it could take buildings, and as a result the city steps down this side of the hill, making the site fairly challenging for many tourists. The more feeling guidebooks advise you to take a taxi to the acropolis and walk down into the later city.

Pergamum seems to have had the same set of walls from the fifth to the third century BC, with an interior division between a 4.5-hectare fortress/citadel/acropolis at the northern (highest) end of the hill, and a 15.5–hectare town below it. The acropolis contains a series of rather grand Hellenistic houses that are usually taken to be the palaces of the Attalid monarchs (although everyone has different ideas about which king lived in which palace), together with a sanctuary of Athena, and a very grand temple that Hadrian dedicated to Zeus and his predecessor Trajan, as well as to himself.

The acropolis also contained the famous Attalid library, said to have held 200,000 books and to have rivalled the Library of ALEXANDRIA until Mark Antony gave its contents to Cleopatra as a wedding gift. The word ‘parchment’ (pergamenum in Latin) was named after the city of Pergamum, where its use was perfected under the Attalids – reportedly during a time when Egypt was withholding papyrus from its rival library.

On the west side the slope of the hill was adapted to form a theatre; this has the steepest rake recorded for any Greek theatre and provides a memorably dizzying experience, no play needed.

Immediately below the acropolis lie the remnants of Pergamum’s most famous monument, the Great Altar. This was built by King Attalus I to celebrate a victory over the Asian Gauls (St Paul’s Galatians) in 230 BC. The battle was presented as the triumph of the Olympian gods over the netherworld giants (i.e. order over chaos) in a long frieze encircling the altar. What has been recovered is now in Berlin, where, painstakingly reconstructed, it forms the centrepiece of the Pergamum Museum; all that has been left onsite are the foundations. The other public buildings in this part of town are relatively minor: a heroon (a shrine for the cult of Hera favoured by the Attalid monarchs) and a small agora. It is safe to assume that most of the rest of the available area – a very cramped 15.5 hectares – was residential.

In the early second century, Eumenes II extended the town to the bottom of the hill and ran a new wall around the hill’s base. This increased the intramural area more than fourfold (from twenty hectares to ninety), but given the nature of the ground it is most unlikely that the built-up area increased in the same proportion. There was, however, enough space for some impressive public buildings: a three-level gymnasium (for men, boys and children), a sanctuary of Demeter and a much grander agora than the one in the upper town.

Under the Romans the focus of activity moved from the hill to the level area on the south-west, on the far side of the Selinos river. Here an extensive area – perhaps as much as 125 hectares – was surveyed and then divided up into the sort of urban grid beloved of Roman planners. They stuck to this layout so rigidly that when a major project ran up against the Selinos, they covered over an entire section of the river and placed the large serapeum (also known as the Red Basilica) on top of it. This structure, a temple to the Egyptian Gods, still stands today, a huge mass of brickwork straddling the Selinos, which flows through twin tunnels underneath it. In front of the temple was the Roman forum; on the western side of town there was the usual entertainment complex: a stadium, an amphitheatre and a theatre (the latter able to accommodate 30,000 spectators, as compared with the 10,000 that could fit into the Hellenistic theatre on the hillside). All these buildings seem to have been erected in the reign of Hadrian, and the amphitheatre is particularly interesting. Built over a river, its arena could be filled with water to stage mock naval battles. As there is no reason to believe that the population of Pergamum had suddenly doubled when these buildings were added, the assumption has to be that this Hadrianic programme represents a relocation of the town from hill to plain, not the addition of a suburb.

In the Byzantine period the movement was reversed. Most of the remains of this recolonization of the hill have been removed by archaeologists eager to get at the classical levels, but the walls built around the acropolis in the seventh century, and around the lower town in the twelfth (some say the end of the thirteenth) are still standing. In each case they enclose a slightly larger area than their Hellenistic equivalents (nine hectares plus 16.5 hectares, making a total of 25.5 hectares).

Pergamum under the early Attalids can only have had a small population: there simply wasn’t room on the hilltop for more than a few thousand souls. With the extension of the city by Eumenes II the increase in the intramural area to ninety hectares means that, in theory at least, there was space for a population of 10,000 or more, but the reality is that much of the ground is too steep to be of use without extensive terracing, and only the southern face of the hill shows significant traces of that. A population of 10,000 requires an extramural spillover, something for which there is no evidence before Roman times.

This brings us to Roman Pergamum, the unwalled town on the west bank of the Selinos. As is almost always the case with classical sites, considerable knowledge of public buildings is balanced with an almost complete lack of data about the humdrum dwellings that made up the bulk of the development. The amphitheatre, Roman theatre, stadium and Temple of the Egyptian Gods poke up through the Turkish town, but the houses of the people are still buried beneath it. As a result we can’t be sure how far the new town extended, although something of the order of seventy hectares is probably a reasonable guess – certainly this is enough to contain all the known remains of the Roman period (bar graves). As regards population, this suggests a figure of around 7,000, putting it in the same ballpark as Hellenistic Pergamum. Add a few thousand for those left behind in the Greek town – priests and servitors for the temples, pedagogues and pupils for the gymnasia – and the population total is somewhere around the 10,000 mark. At a stretch this could apply to the whole Roman period from 150 BC to AD 250.

By 1900 the Ottoman town, after centuries of slow and irregular growth, covered an area of about ninety hectares. It was then thought to have about 15,000 to 20,000 inhabitants, but the first census, taken in 1927, counted only 13,000.