Campania, Italy

Town on the Bay of Naples buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79

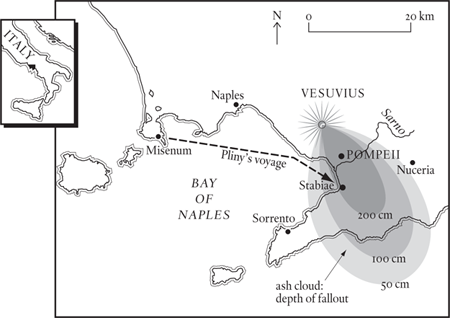

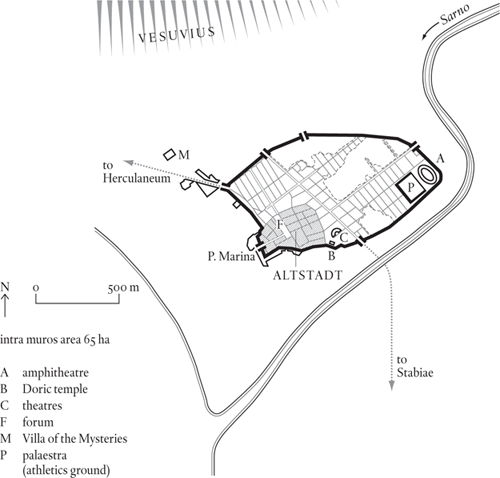

Pompeii is situated near the ancient mouth of the Sarno, a small river that runs along the southern side of Vesuvius. The initial nucleus seems to have been Greek, and dates from the sixth century BC, when this part of the Italian coast was dotted with outposts spun off from the colony that pioneered Greek settlement in the area, the eighth-century polis of CUMAE. A Doric temple on the southern edge of the town, in what subsequently became the ‘Triangular Forum’, is the sole surviving evidence of this Greek initiative, which may never have amounted to much more than the temple and its surrounding sanctuary. Eventually something more significant in the way of a settlement did appear, centred on a temple of Apollo 300 metres to the west of the Greek sanctuary; the major influence now was Etruscan rather than Greek. This old town – referred to in some archaeological literature as the ‘Altstadt’ – was very small, covering only about nine hectares, but by the late fifth century it was the focal point of an independent community. If there had ever been Greek or Etruscan political control, this had long since ceased to be effective, and historians consequently classify the town as Campanian (from the region), Sabellian or Samnite (alternative designations of the south-central Italian indigenous people), or Oscan (from the language these people spoke).

In the latter part of the fourth century, the Campanians were drawn into the struggle between the rising power of ROME and the Samnite confederacy of the south-central Apennines. They chose Rome, the winning side, and for the next 250 years – through the third and second centuries BC and the opening decade of the first – Pompeii led an uneventful life as a self-governing community in alliance with (meaning subordinate to) the Roman Republic. This status, shared with many other Italian communities, was less than the Pompeiians thought they deserved, and in 89 BC they joined the anti-Roman uprising known as the Social War (from socii, meaning ‘allies’). The rising was brutally suppressed, and although the Romans then proceeded to grant the defeated communities many of the legal rights they had been seeking, this was small compensation to the Pompeiians for their loss of separate identity. The victors declared the town a Roman colony in 80 BC and discharged Roman soldiers took over much of the native Pompeiians’ property. The upper echelons of Pompeiian society were completely Romanized, with Latin replacing Oscan not just in official documents but in everyday speech. The new Pompeii became, for all practical purposes, a purely Roman town.

It was quite a big settlement. At some stage in the Oscan period a new circuit of walls had been constructed enclosing no less than sixty-five hectares. The street layout suggests that this very considerable area came into use one sector at a time, starting with the area north-west of the Altstadt. The next zone to be developed was the band of territory either side of the road connecting the Vesuvian and Stabian gates, and the last phase of development was the eastern half of the city. The density of housing clearly falls off as you go from west to east, and some of the blocks at the far end remained open ground.

The amphitheatre, built in the years immediately after the Roman takeover, seems to be the oldest surviving example of such a structure. It was dedicated in 70 BC to Gaius Quintius Valgus and Marcus Procius, two Roman military commanders who became magistrates of the town after it was joined to the republic, and it is located at one corner of town on what had presumably been a greenfield site.

In its final Roman phase, Pompeii was rarely in the news. The biggest headline it got was in AD 59 when there was a riot in the amphitheatre during a gladiatorial show. Visitors from the neighbouring town of Nuceria were attacked by Pompeiian rowdies; many were injured and some were killed. The Nucerians complained to the authorities in Rome, and the Roman Senate, after pondering the matter, decided to punish Pompeii with a ten-year ban on public gatherings of any sort, a woeful penalty in that era of bread and circuses.

The eruption of AD 79

One clear sign that Pompeii was in some sort of geological trouble came in AD 62 when the town was seriously damaged by an earthquake. We know now that the shock was caused by a plume of magma forcing its way up to a point under the supposedly extinct crater of Vesuvius, but to the Pompeiians it was a one-off event, a disaster certainly, but not one that carried any warning for the future. Their preoccupation was getting the town up and running again, and both public and private energies were bent to this end.

The lists of buildings that were – and weren’t – repaired over the next seventeen years is interesting. Most of the housing was made habitable again, and some of the richer citizens had their houses completely redecorated. As regards public buildings, top priority was given to the amphitheatre, theatre and baths, all places that had important roles in the good life as perceived by Pompeiians. Funds were even found to build a completely new set of baths, the Central Baths, in the most up-to-date style. As to temples, there was money for a lavish restoration of the Temple of Isis, a private cult, and work was started on rebuilding the Temple of Apollo, the tutelary deity of the city, but nothing was done to restore the Capitolium in the forum, a grand temple of Jupiter at the centre of the town. Doubtless the Pompeiians would have got around to it in time, but it clearly wasn’t a priority. The saddest loss was the earthquake damage to the Alexander mosaic, Pompeii’s finest artwork, which was in a house that had been built by a patrician family back in the second century BC. Like most grand families, they had come down in the world in later years, for there was no attempt to repair the damage; the missing segments were simply filled in with plaster.

Such then was the condition of Pompeii in August AD 79. Minor earthquakes still troubled the town, but the Pompeiians had learned to live with them. They had recovered their lifestyle thanks to a generous outlay of self-help, along with the fertility of the volcanic soil that they tilled.

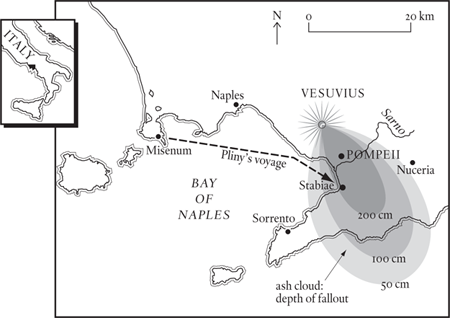

What happened next is described by Pliny the Younger, who was staying with his uncle at Misenum on the other side of the bay from Pompeii. In the early afternoon of 24 August, his attention was drawn to a strangely shaped cloud rising from a mountain in the general direction of Vesuvius. It was like an umbrella pine, says Pliny, with a long vertical trunk and a flat top – what we would call a mushroom cloud, and just as ominous. Pliny the Elder, who had charge of the fleet at Misenum, was sufficiently intrigued to order a warship readied so that he could take a closer look; his nephew, a bookish young man, turned down the offer of a place on the boat, preferring instead to continue making extracts from his copy of Livy. Aided by a northerly wind (specifically north-north-west) and spurred on by a message pleading for help from an acquaintance with a villa at the foot of Vesuvius, the elder Pliny set sail, using the mysterious cloud as his mark.

The same wind that sped Pliny the Elder on his way blew the top of the mushroom cloud directly over Pompeii. As a result, the town received a steadily thickening coat of ash. The pumice stones that were included in this fallout were too light to do significant damage to people or property, but as the accumulated ash reached a depth of 2.8 metres, some roofs caved in. For some, the increasing burden of ash, earth tremors of mounting intensity and the sight of fires burning on the flanks of Vesuvius proved too much and they fled into the countryside. Others decided to tough it out and stay with their property. This was the wrong decision: the nature of the eruption was changing as the throat of the volcano began clogging up, leading to intermittent collapses of the gas-driven column of ash, followed by explosions that temporarily cleared the throat, but also destroyed parts of the volcano’s rim. Because of this, each of these explosions launched a cascading mass of searing hot gas, ash and rocks down the sides of the mountain. Early on the morning of 25 August, one of these pyroclastic flows reached the north wall of Pompeii; not long after, another overflowed the wall and tore through the city – flows of this sort can travel at speeds in excess of 100 kilometres per hour (60 mph). Every living thing in the town was killed, near enough instantly. This and a second pyroclastic flow that followed an hour later added another one to two metres to the shroud covering the city, and subsequent airborne ash another metre. By the time it was all over, Pompeii was buried to a depth of five to five-and-a-half metres, and only the tops of the tallest houses were visible, poking up through this mass of volcanic material. Both town and townsfolk had been snuffed out.

Pliny the Elder didn’t succeed in his rescue mission, as rafts of pumice prevented him from reaching the shore in the vicinity of Vesuvius. He diverted to Stabiae, where the next morning he died, perhaps coincidentally (he was fifty-five, a good age for the time), but more likely because his lungs failed in the ash-laden, partly poisonous air.

Pliny the Younger, observing events from Misenum, continued his studies undisturbed through the first day of the eruption, but that night there were a series of earthquakes that were alarming even by Campanian standards. At dawn, he and his mother, fearing that the villa was about to collapse, moved on to open ground. From there, Pliny saw a particularly massive earthquake suck the sea back from the shoreline, ‘leaving sea creatures stranded on the dry sand’ before driving the waters back again. Then a shift in the wind brought the ash cloud over Misenum, plunging the whole northern peninsula into darkness. When an anaemic sun finally broke through, it was early evening and Pliny was left wondering at how ‘everything was changed, buried deep in ashes like snowdrifts’.

Rediscovery and excavation

In 1594, the digging of a water channel across the site of Pompeii uncovered frescoed walls, and even an inscription giving the name of the city. Alas, scholars misinterpreted this as a reference to Pompey the Great and decided that the remains were those of a large villa of his. Planned excavations took place in 1748, after enthusiasm for archaeology of a primitive, treasure-hunting sort had been aroused by the earlier discoveries at HERCULANEUM in 1709. Herculaneum, sealed by rock, was very hard to tunnel into. By contrast, Pompeii’s shroud of ash and earth was easy to shovel aside. As a result, Pompeii soon became the main focus of the Bourbon monarchy’s explorations, and the diggings at Herculaneum were gradually abandoned. That ‘Pompey’s villa’ was in fact a major town soon became apparent. At first it was thought to be Stabiae; then the discovery of another inscription confirmed its true identity.

For the first hundred years, the work done at Pompeii amounted to little more than an ill-organized ransacking of the site, with spoil dumped over areas deemed exhausted, and many finds reburied so that they could be ‘discovered’ by visiting dignitaries. Records were almost non-existent, the works of art uncovered often sold to foreign collectors. But gradually things improved, and after 1860, when Giuseppe Fiorelli was appointed director, the quality of excavations started to match the unique value of the site. Where possible, finds were left in situ; where that wasn’t practical, they were deposited in the Museo Nazionale in NAPLES. Disorder retreated, just as a new threat emerged in the form of mass tourism.

Since the Second World War, the priority has been the preservation of the existing remains; new work has, quite rightly, been confined to the clarification of the existing plan. The unexcavated area (approximately one-fifth of the town) remains for the attention of a future generation.

There seems to be general agreement that the number who died when Pompeii town was overwhelmed is of the order of 2,000 to 2,500. This is based on a body count of 1,000 to 1,500, plus an additional percentage to take account of the skeletons lost or unobserved in the early, erratically recorded excavations, and the size of the area that remains unexcavated.

Unfortunately, this figure is little help in determining the total population, because no one knows how many fled the city before the final disaster. Giuseppe Fiorelli thought in terms of a population of 10,000 to 15,000. The tendency of late has been to lower this, as in Frank Sear’s Roman Architecture (1982), to ‘no more than 10,000’. The most closely reasoned figure is that given by J. C. Russell in The Control of Late Ancient and Medieval Population (1985), who reckoned that a town like Pompeii, where almost all the housing was single storey, is unlikely to have had a population density greater than the average for late medieval cities where the houses were generally two storey, and often three. This average is 100 to 120 per hectare, suggesting a population for Pompeii of 6,500 – say 7,000 with suburbs.