Calabria, Italy

Classical Rhegium; capital of the late Roman province of Lucania and Bruttii

Towards the end of the eighth century BC, the Greeks settled on either side of the Strait of Messina, the narrow channel that separates Sicily from Italy. The initial settlement was on the Sicilian side, at Messina, but the Messinians knew that if they were to succeed in their aim of controlling traffic through the strait they needed a matching settlement on the Italian shore. They found a suitable site at present-day Reggio, on the tip of the Italian toe, and within a few years a group of colonists from Chalcis in Euboea was ensconced there, the Messinians providing whatever backup was needed to make things run smoothly. And although Reggio was never a very large place, it seems to have been successful enough, the only setback coming in 387 BC when Dionysius I of Syracuse, who had no intention of letting anyone interfere with his use of the strait, subjected the town to a bruising sack.

A new era opened for Reggio in 282 BC when the city fathers requested a Roman garrison, perhaps because they felt threatened by the local Italic tribe, the Bruttii, but more likely because they saw the way things were going in this part of the world. Having formed this alliance, the citizens kept faith with Rome, rebuffing the forces of both Pyrrhus and Hannibal. Thereafter Reggio settled into a comfortable obscurity until the end of the third century AD, when it became the seat of the corrector (governor) of the new province of Lucania and Bruttii. Its walls were still intact, and its population sufficient to defend them, during the Gothic wars of Justinian’s reign (AD 535–52); subsequently, it is safe to assume that Reggio shared in the contraction in population and resources experienced by Italy in the Dark Ages, and that it was during this period that the classical perimeter was abandoned.

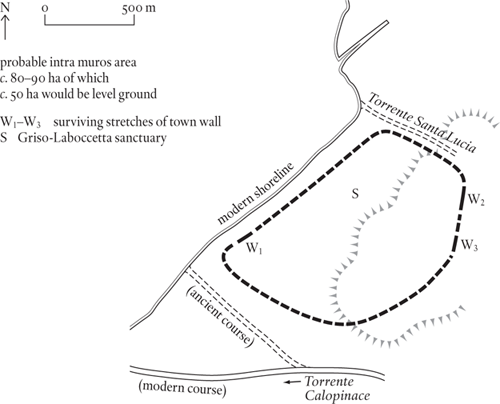

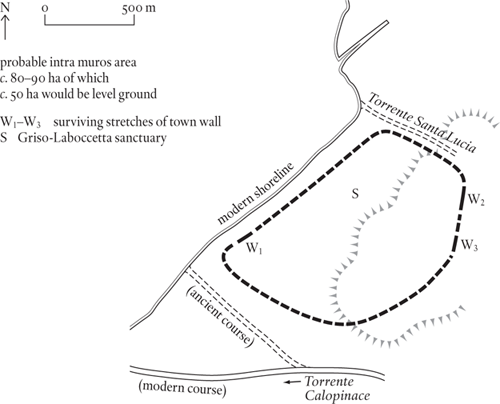

As this account will have made clear, very little is known about Reggio, and this is as true of its layout as its history. The town was built on a strip of level ground between the terminal hills of the Aspromonte range and the sea, its flanks defended by two seasonal rivers, the Santa Lucia in the north-east and the Calopinace in the south-west. The shoreline was straight, as it is today; the town wall ran along the seafront then inland to take in the summits of the three nearest hills. A short stretch of the wall on the seafront, handsomely built in stone, is still in situ; two stretches of a mud-brick wall survive in the hills. These and the geographical constraints of the site suggest that the intramural area is about eighty to ninety hectares, of which, at the most, fifty hectares would have been built over. Nothing is known of the street plan and although Roman inscriptions mention several public buildings – baths, a basilica, a temple of Apollo and another of Isis and Serapis – none of these structures has been located. The only significant discoveries have been the fragmentary terracotta sculptures found in the ‘Griso-Laboccetta sanctuary’, which come from an altar or temple of the late sixth century BC.

Reggio was clearly never a large place, being overshadowed by its Sicilian counterpart, Messina, throughout its history. Its population first reached the 10,000 mark in the early nineteenth century. It is unlikely to have come anywhere near this figure before.