Marne, France

Classical Durocortorum Remorum, county town of the Remi; capital of the province of Belgica in the early Roman Empire and of Belgica Segunda in the fourth century

On the eve of the Roman conquest, Reims was one of the more important of the oppida of north-west Gaul. Oppida were tribal meeting places, not towns, but the Romans were keen to see them develop into genuinely urban structures, seeing this as part of their civilizing mission. They had a particular interest in this process in the case of Reims, for the Remi, the Belgic people for whom Reims was the tribal centre, were both powerful and pro-Roman. Caesar had benefited greatly from their friendship during his conquest of Gaul, and now that Roman rule was established it was payback time. In the new order of things Reims – Durocortorum Remorum to give it its full title – emerged as the capital of the province of Belgica (north-east Gaul), as well as county town of the Remi.

Despite this mark of favour, early Roman Reims remained a curiously unfocused place. To judge by the distribution of the surviving mosaic floors, there seem to have been almost as many Roman dwellings outside the rampart of the oppidum as inside, and there is no evidence for the features characteristic of Roman urbanism: no sign of a theatre, or amphitheatre, or any baths, public or private. Most of the negativity in this picture is probably due to the complete rebuilding of Reims in the medieval period, but it is true to say that the few constructions that do survive are late rather than early: the town’s gates, and the cryptoporticus under the forum are all dated to the period AD 175–250. At the moment it looks as if the town fathers only decided to make Reims a truly Roman city at that time. Until then they were apparently content to let the inhabitants determine the configuration of their town.

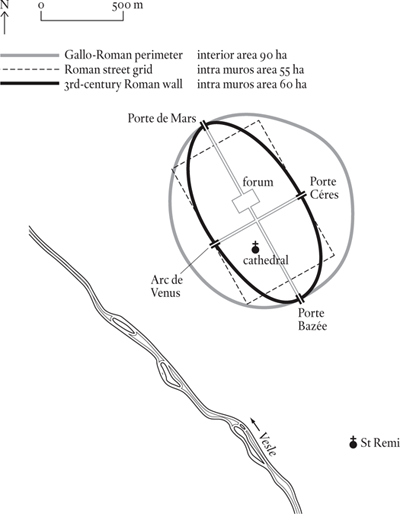

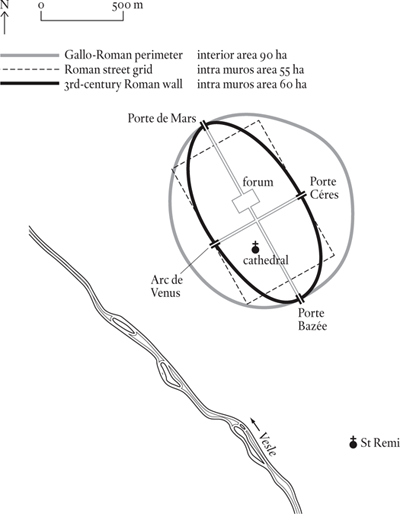

Celtic and early Roman Reims had been defined by a roughly circular rampart enclosing an area of about ninety hectares. Within this, Roman planners at some stage laid out an orthogonal street grid in a rectangle covering some fifty-five hectares. The north and south gates were sited on the line of the rampart, beyond the edges of the rectangle. The east and west gates were placed within the rampart, at the edges of the rectangle. Aside from the fact that the forum was just north of centre, that is almost all we know about middle period (early third-century AD) Reims. In the second half of the century a defensive wall was built, probably as a rush job, which completes our picture of the town. It followed an economical, oval course, connecting the four gates while cutting off the corners of the original rectangle. The area enclosed was about sixty hectares.

Long though Roman memories were, there came a time when the services of the Remi to the Roman state began to seem less important than the town’s geographical disadvantages. Its rival, TRIER, was better positioned as regards the administration’s main preoccupation, the Rhine frontier, and as the years passed, more and more functions were switched to the city on the Mosel. After the late third-century crises, Trier emerged the clear winner and Reims had to content itself with less exalted status. It remained, however, the seat of the governor of Belgica Segunda, one of the new small provinces created in Diocletian’s reorganization of the empire, and, of course, it continued to be the county town of the Remi.

Reims acquired a Christian community by the third century and in the course of the fourth this became the dominant element in the city’s life. There are records of several churches, most notably the cathedral dedicated to the Virgin standing on the same site as the present-day building. Although the founder of the cathedral, St Nicaise, was to perish when the Vandals sacked the city in 407, the ecclesiastical organization survived this blow and St Remi, who became bishop in 459, was able to engineer a remarkably successful transition from Roman to Frankish rule. His culminating triumph was the baptism of Clovis, king of the Franks, in 498, the start of a tradition that was to bring French kings to Reims for their coronation for as long as the monarchy lasted.

When St Remi died he was buried in the cemetery to the south of the city. In the sixth century a basilica was built over his tomb and it was this basilica, not the cathedral, that attracted the pilgrims who flocked to Reims to seek intercession of the saint. The result was that Dark Age Reims acquired a second focus, in exactly the same manner as TOURS. Fortified in the early tenth century, this ‘Châteauneuf de St Remi’ sustained its separate character until the thirteenth century.

Reims was always one of the most important towns in Roman Gaul, and it was to make a good showing in the medieval period too – not quite in the same league as Rouen or Toulouse, but not far behind these pacesetters in the resurgence of urban life. A new, more extensive wall built in 1209–1358 joined the town to the Châteauneuf de St Remi and brought the area between these two and the River Vesle within its circuit. This increased the intramural area to 200 hectares, far more than was needed, but indicative of the resources available to the town fathers of the early fourteenth century. We are fortunate in having a house count for this period; it suggests a population in the 12,000 to 15,000 range, which in turn suggests a Gallo-Roman population of about half this, i.e. something in the region of 6,000 to 7,500. This would only have been achieved in the periods of maximum prosperity, the mid first to mid third centuries AD, and numbers would then have declined in step with ROME’s fortunes. By AD 500 the total must have been under, rather than over, the 1,000 mark and it would have stayed there for the remainder of the Dark Ages.