Yonne, France

Classical Agedincum; county town of the Senones and capital of the late Roman province of Lugdunensis IV

The Senones were one of the more important of the Celtic tribes of Gaul, with a particularly impressive past: a branch of the Senones spearheaded the Celtic invasion of Italy and, under the leadership of Brennus, put ROME itself to the sack in 390 BC. Three and a half centuries later when Caesar invaded Gaul, the boot was on the other foot. In 53 BC, the Senones resisted Caesar’s selection of Cavarinus to be their ruler, leading to two years of hostilities. At the end, they were absorbed like other Gallic territories into the Roman provincial system.

Despite the prominence of the Senones, their county town, modern Sens, was not recognized as having any particular distinction until the closing decades of the empire. In the first three centuries AD it was merely one of two dozen county towns in the province of Lugdunensis; after the division of the provinces in 297, it occupied a similarly undistinguished position in the roster of Lugdunensis I. But when the emperor Valens subdivided Lugdunensis I in 375, it became the provincial capital of the northern half, Lugdunensis IV, alternatively known as Lugdunensis Senonia, or simply Senonia. Sens now stood above the other towns of the new province, including such ultimately far more famous places as PARIS and Orleans. This rank it retained until the collapse of the Roman Imperium in Gaul that began in 406 with the invasion of the Suevi from across the Rhine.

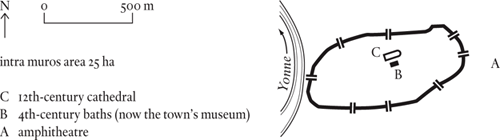

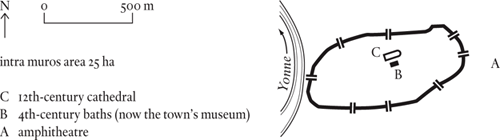

Late Roman Sens had a fine town wall dating from the 260s, the period when Gaul first came under attack. It enclosed an area of twenty-five hectares, a considerable area in that era of declining prosperity. Unfortunately, the wall was pulled down in the 1840s and as it was the only significant structure surviving from the Roman period, there is now nothing of Roman date to see in the town apart from one surviving tower (out of twenty-three) and the reconstructed facade of a bath building just to the south of the twelfth-century cathedral. So we don’t know if the town was originally bigger, as is often the case in Gaul, or if the late Roman circuit enclosed the entire built-up area. Either way, the population is unlikely ever to have been more than 2,000 to 3,000.

One curious survival is Sens’ position in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The clerical order of seniority held to the Roman model long after it had ceased to be relevant, with the archbishop of Sens still outranking his colleague in Paris until the 1620s, at which time Paris had a population of 200,000, compared to Sens’ 5,000.

Presumably because the lack of remains is so discouraging, no one has attempted to publish a connected history of the Roman town.