Hampshire, England

Classical Calleva; county town of the Atrebates of southern Britain

Unusually for a Romano-British town, Silchester seems to have had a significant pre-Roman history. The evidence for this is an inscription on a coin issued by a chieftain of the Atrebates some time around AD 5–10, in which he calls himself ‘Eppillus rex Callev’ (Epillus, king of Calleva). Not that there is much to say about Calleva in its pre-Roman phase. All that has been discovered so far is that a bank of earth was built around the site and then almost immediately replaced by another one enclosing three times the space (ninety-five hectares, compared to thirty-three).

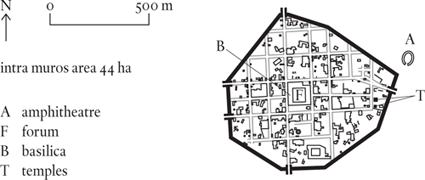

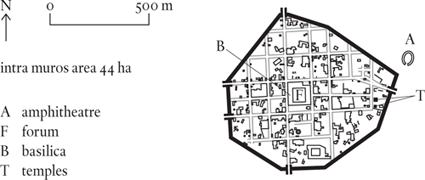

The larger circuit proved far too ambitious. When the Romans took over direct responsibility for the region (c. AD 80), after a forty-year period in which the Atrebati continued under the rule of their native chiefs, they reduced Calleva’s area to eighty-six hectares. When the Romans eventually fortified the town (c. AD 165–95) the area enclosed was only around forty-four hectares. Something of this order is what one would expect for a Romano-British county town, and there is no evidence to suggest that the built-up area of Silchester ever exceeded this figure. Quite the opposite: the inhabitants of the town always had plenty of room to spare.

This brings us to the reason for this entry. Silchester has no special historical interest: it simply served its local function for 350 years and then faded away. Nor does it offer the present-day visitor much in the way of sights: the wall still stands, but all that it encloses is a field or two, a farm and a tiny church. But the fact that it has lain open to the sky ever since it was abandoned in the early fifth century has given archaeologists a rare opportunity to excavate a Romano-British ‘city’ in toto. Thanks to the patronage of the local landowner and the energy displayed by the Society of Antiquaries, this opportunity was splendidly taken in the late nineteenth century; as a result we have a plan for Silchester that is essentially complete. It is our best bit of evidence on Romano-British urbanism.

Silchester had a street grid with a forum at its centre. It had a set of baths, an inn and, outside the east gate, an amphitheatre. This is all pretty standard stuff, neither more nor less than one would expect for a town in this class. What Silchester didn’t have was many houses – 150 at the most and, for much of its history, probably no more than half this number. Moreover, most of the houses were small so it is unlikely there were more than four or five occupants per house – medieval figures suggest that even this will be a high average. So we are talking about a population of 750 people at a maximum, and very likely only half this number for much of the time. This is very different from the usually accepted picture of Romano-British towns as busy places with crowded streets and a generally urban air to them.

The truth is that Roman Silchester must have been a sleepy place with wide spaces between its buildings. The majority of the houses would have been little more than shacks, and the few public buildings little better than barns. Insofar as it was more than a village, it owes its extra status to Roman administrative formalism; it had no significant trade or industry or function of its own and as soon as the Romans left, it died.