Present-day Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia

Capital of the province of Pannonia Secunda; residence of the prefect of Illyricum; diocese: Illyricum

An oppidum of the Illyrian Amantini, Sirmium was occupied by the Romans during their conquest of Pannonia, probably by Tiberius in 13 BC. It was not, so far as we know, ever a military base but its Roman population must have grown rapidly because it was already sufficient to fend off the natives during the Pannonian revolt of AD 6–9. Subsequently Romanization was carried through to completion, an achievement that was recognized in AD 79 when Vespasian gave the town colonial status.

Sirmium’s success must have owed a lot to local factors, in particular to its situation near the Save’s junction with the Danube, but its position in the wider Roman world was the key to its real importance. In the later second century AD, the Roman Empire was forced on the defensive as Germanic tribes repeatedly challenged the Danube frontier. Sirmium emerged as a useful command and control centre for the central sector and as such was used by the emperor Marcus Aurelius during his Marcomannic war in 173. Fifty years later, the soldier emperor Maximinus Thrax (235–8) spent most of his brief reign in the town directing operations. It is at this time that we find Sirmium being referred to as ‘the largest city in Pannonia’ (Herodian VII.2.9). When the Danube line finally collapsed in the 260s, Sirmium was one of the few places that managed to hold out. We have no details of its travails apart from a brief mention of the fate of the emperor Probus, who was murdered by mutinous soldiery in the town’s Iron Tower in 282, but when order was finally restored, Sirmium’s strategic importance was given formal recognition. As part of the package of administrative reforms initiated by Diocletian in the last years of the third century, Sirmium became the residence of the prefect of Illyricum, one of the half-dozen most important officials in the empire, as well as being made the provincial capital of Pannonia Secunda (the southern half of what had previously been Pannonia Inferior). A few years later the town reached its peak. It served the emperor Licinius as his capital from 308 to 314, and when Constantine the Great chased him out, its metropolitan status was enhanced, not diminished. Constantine, who was in residence from 316 to 321, held the city in the highest esteem, and seems to have seriously considered making it the empire’s senior capital. But this was not to be: Constantine moved on to the conquest of the Eastern provinces, and eventually created his New Rome on the shores of the Bosporus.

Although its days as an imperial city were now over, emperors continued to stay at Sirmium when they were visiting the area. Constantius I was there in 351, and Valentinian I in 374. But Valentinian found the city in a sorry state, its walls crumbling and its moat full of garbage (Ammianus Marcellinus, 29.6.3). Prodded by Valentinian, the prefect cleaned out the moat and used materials collected for a proposed rebuilding of the theatre to patch up the walls. But the root problem, the crumbling of the local economy, was not so easily addressed. Eventually the attempt to hold on to the Pannonian provinces was abandoned, the whole area being ceded to the Huns in 441. After the collapse of the Hun Empire, the region passed to the Ostrogoths (454), the Gepids (474), back to the Ostrogoths (508) and then back to the Gepids (537). After the defeat of the Gepids by the Avars in 567, the East Roman emperor Justin II managed to sneak a garrison into Sirmium, in a move that annoyed the Avars more than somewhat. Eventually, in 582, the Avars took the town; whatever part of it was still inhabited went up in flames the next year.

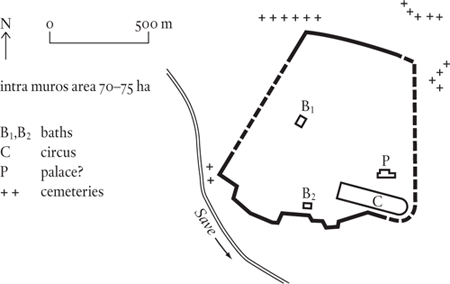

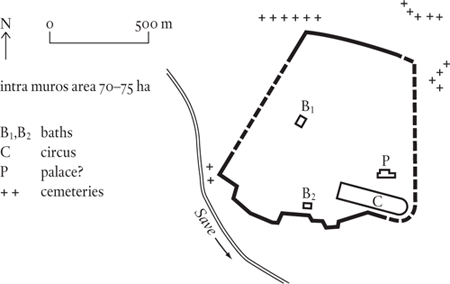

Some preliminary excavations have uncovered the northern and southern sectors of the city wall, some baths and a circus, all dated to the early fourth century. It seems probable that the main feature of late Roman Sirmium was an imperial palace of the type developed under the Tetrarchy. The intramural area appears to be of the order of seventy-five hectares, suggesting a peak population of about 7,000. Something around the 5,000 mark is a plausible figure for the earlier period (100–250).