Present-day Izmir, Aegean Turkey

The eleventh century BC saw the beginning of a trans-Aegean migration that brought Greeks of various sorts from peninsular Greece to the western coast of Anatolia. The Gulf of Smyrna was supposedly settled by Aeolians (Greeks from the sector north of ATHENS), but early on they seem to have been joined by groups of Ionians (Athenians and their immediate neighbours), which led to some confusion of loyalties. The settlement prospered, and by the seventh century BC there was a small town, now known as Old Smyrna, on the north side of the gulf, acting as the focus for a farming community that had spread around the coast to the south side and a short distance – a few kilometres only – into the interior. This was the situation when Alyattes, king of the inland state of Lydia, decided to establish control over the coastal communities that fringed his kingdom. When the Smyrniotes demurred, Alyattes reacted with vigour, storming Old Smyrna, expelling its inhabitants and razing it. The Smyrniotes became a purely rural community, paying taxes to the Lydian king, and subsequently to the power that succeeded him in Anatolia, the empire of the Medes and Persians.

This depressing state of affairs was brought to an end by Alexander the Great in 334 BC, when, as a first step in his invasion of the Persian Empire, he liberated the Anatolian littoral. The Smyrniotes were now able to think in terms of reconstituting themselves as a proper polis, with an urban centre where the business of the community could be conducted with dignity. The site they picked was on the south side of the gulf, some eight kilometres (five miles) distant from the ruins of Old Smyrna. According to later legend it was Alexander himself who decided on this position. One of his hunting expeditions took him to the slopes of Mount Pagus where our hero, exhausted by the chase, decided to take a short nap. While he slept he dreamt that two young ladies – later identified as water nymphs from a shrine nearby – had appeared before him and commanded him to build the Smyrniotes’ new city on this very spot. And so Mount Pagus became the acropolis of New Smyrna.

Be that as it may, nothing practical seems to have been done until the Macedonian general Lysimachus took over the area thirty-three years later. He found the resources necessary for the project and by 288 BC, when Smyrna was enrolled as the thirteenth member of the Ionian League, the work must have been far enough along for the city to have become a reality.

Lysimachus clearly hoped that Smyrna would be an important place, and its subsequent history fulfilled his expectations. By the Roman period it was accounted the third city in the province of Asia (the western third of Anatolia), after PERGAMUM, the titular metropolis, and EPHESUS, the de facto capital. By the Smyrniotes’ own account, they were really number one; they had no hesitation in proclaiming their city ‘First in Asia for beauty and size’ and even, more debatably, as ‘Metropolis of Asia’. This self-advertisement came a bit closer to the truth with the rapid decline of Pergamum, but Ephesus continued to outrank Smyrna to the end of antiquity. The best the Smyrniotes could do was get the ecclesiastical authorities to confer independent status on their bishop so that he did not have to answer to the archbishop of Ephesus.

The history of Smyrna in late antiquity is an almost complete blank. Its fortifications were apparently maintained in good order: surviving inscriptions commemorate restorations of the east gate by Arcadius in the fifth century AD and by Heraclius in the seventh. So far as we know, no enemies ever gained entry even in the empire’s darkest days, and the city appears to have survived the secular decline of the Mediterranean economy much better than most places of which we know. Certainly it was still a significant place in 1076 when, in the aftermath of the imperial catastrophe at Manzikert, it was seized by a Turkish adventurer named Chaka. He made it the centre of a pirate state that included Chios and Lesbos, before being evicted by a Byzantine army in the counter-offensive that followed the First Crusade. The city was a prize worth fighting for, as it was now the only port of significance on the Aegean coast of Anatolia, and this at a time when trade was picking up again. The main trading partners were the Genoese, and when the Byzantine state began to go under in the early fourteenth century, it was the Genoese who took control of the city, hoping to protect it from the encircling Turkish tribes. They didn’t succeed: the city fell in 1329 and although a Holy League of Crusaders, put together by the Pope, got half of it back again in 1344, this partial success was the best the expiring Crusader movement could manage. For the next sixty years the town was divided, with the Crusaders holding the harbour and the Turks the citadel, an odd situation that finally came to an end in 1402 when the Great Emir, Timur the Lame, stormed the harbour defences and erased this, the last Christian enclave on the Aegean littoral. As usual, Timur did such a thorough job that nothing much was left of the city, and even a century later Smyrna – Izmir to the Turks – had no more than 1,500 inhabitants. The harbour basin in use since antiquity silted up during this period. Today, it is built over and lies underneath the present-day bazaar. Smyrna’s later recovery began at the close of the sixteenth century, and the runaway growth that established Izmir as one of Turkey’s major cities began in the seventeenth century.

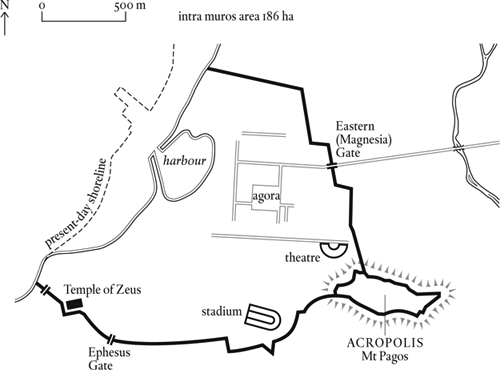

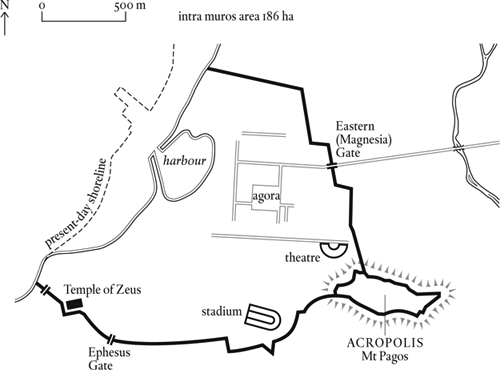

Smyrna has a splendid site, and a visitor standing on Mount Pagus in Roman times would have been favoured with a fine urban prospect: a stadium and theatre at the foot of the hill, long straight streets running down to the curve of the gulf and, on an eminence at the southern end of the shoreline, a massive temple of Zeus. In the centre of town and on the same orientation as the street plan there was a spacious agora, while somewhere as yet unlocated was a precinct dedicated to the memory of Homer, reflecting Smyrna’s claim to be the poet’s birthplace. Ancient authorities allowed that this was one of the better claims of this sort.

Classical and medieval Smyrna are now hidden beneath the vast sprawl of modern Izmir, and there are few remains of either to be seen. Most impressive is the agora, which, in its existing form, dates from a Roman rebuilding of the second century AD but is nonetheless fine for that. The theatre and the stadium were both visible in the nineteenth century; now they have vanished beneath houses constructed from their stones. As for the existing castle on Mount Pagus, this contains, despite reports to the contrary, no Greek work at all: it is a purely medieval structure. This is a disappointingly short list for what was clearly one of the most important cities in the ancient Aegean.

Its size and rank suggest that in its heyday, the second century AD, Smyrna’s population was of the order of 20,000. As indicated above, it showed more resistance than most places to the hard times of late antiquity, and probably kept above the 10,000 level until the seventh or eighth century. It is likely that this reflects its durability as a port, although medieval Smyrna was clearly only a minor one.