Apulia, Italy

Greek Taras, Roman Tarentum; capital of the late Roman province of Apulia et Calabria

Taranto was one of a cluster of Greek colonies established in the late eighth century BC on the instep of the Italian peninsula. The traditional foundation date is 706 BC, and the original settlement was supposedly a mix of locals (Messapians, also known as Iapygians), Cretan traders and Spartan colonists. Socially and politically, if not numerically, the Spartan element was the dominant one, and it was to Sparta that the Tarentines turned when they ran into trouble with the peoples of the interior.

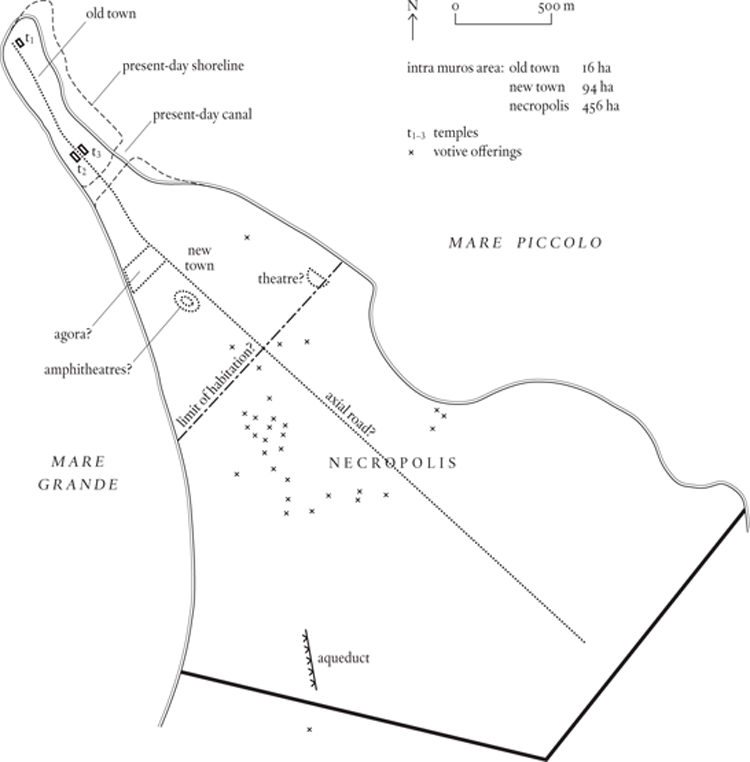

Initially there were no problems of this sort. Taranto, occupying only the tip of its peninsular site, was simply too small to have ambitions that would put it in conflict with the main Messapian tribes. But in the fifth century BC, when the Greek world experienced a new surge of energy, the Tarentines raised their game. They challenged the Messapians in their hinterland, and they made a bid for the leadership of the Greek cities in south Italy by founding a colony named Heraclea. This was supposed to serve as a meeting place for representatives from all of them, with Taranto taking the chair. Nothing much came of these initiatives: the Messapian war ended in defeat, and the Greek cities, whatever their wishes in the matter might have been, were to become dependants of SYRACUSE, not Taranto. What the period did bring was a massive increase in the size of Taranto town. A new wall was built across the base of the Tarentine peninsula, increasing the intramural area from a paltry sixteen hectares to something of the order of 560–70 hectares. Of course, not all of this was built up; four fifths of it remained open ground, with the roads that passed through it lined with tombs, not houses. But if we assume that around 110 hectares was inhabited (including the ‘old town’), that would be comfortably enough to make Taranto the largest community in the heel of Italy, a status that it was to retain for the remainder of antiquity.

The contrast between Taranto’s growth as a town and its failure to establish itself as a political force became increasingly obvious in the fourth century BC. To keep the Messapians at bay, the Tarentines decided to call on their progenitor Sparta for aid, but militarily Sparta was fading even faster than Taranto, and three separate interventions by Spartan mercenaries (in 338, 334 and 303) failed to produce any permanent improvement in Taranto’s position. Worse still, by the early third century BC, the Tarentines were facing a new and much more serious threat in the shape of the rapidly expanding power of ROME. If they were to preserve their freedom, what the Tarentines needed was a state-of-the-art Hellenistic army of the sort that Alexander of Macedon had used to overthrow the Persian Empire. They found their answer in Epirus, a Macedonian satellite whose young king, Pyrrhus, saw himself as a second Alexander and was eager for a western adventure. In 280 BC, Pyrrhus landed in Italy with enough soldiers to defeat the Romans, first at Heraclea, then, the next year, at Ascoli in Apulia. But there was little profit for Pyrrhus in these successes – won at such cost that the term ‘pyrrhic victories’ came to be applied to battles that were as damaging to the victor as the vanquished – and he decided to divert to the more promising field of Sicily. In 275 he was back in Italy again for one more battle, claimed as a draw by the Romans; then he left on another adventure, this time in Macedonia. While he lived he kept a garrison in Taranto, but by 272 his short life was over. The Epirote soldiers went home, leaving the Tarentines no choice but to bend the knee to Rome.

The Tarentines were to get one more chance to re-establish their ancient freedoms. In 218 BC, the Carthaginian general Hannibal arrived in Italy; two years later, at Cannae in Apulia, he turned on the Roman army pursuing him and totally annihilated it. For four years the Tarentines dithered over whether to stand by their ‘alliance’ with Rome, or go over to the Carthaginians, now masters of much of southern Italy. Finally they decided to take their chance with Hannibal. One of the city’s gates was betrayed to him, but he didn’t move fast enough to prevent the Roman garrison withdrawing to the old town, which had retained its fortifications. The result was a stand-off between the Carthaginian-Tarentine force in the new town and the Romans holding what was now referred to as the citadel. After three years of this, some of the Tarentines, conscious of the slow but steady weakening of Hannibal’s position, played the same trick on him as they had on the Romans. A Roman army entered the city by night, linked up with the force holding the citadel and slaughtered the Carthaginian garrison, the Tarentines who had supported the Carthaginian cause and anyone else whose looks they didn’t like.

After these excitements, Taranto finally accepted its role as Rome’s strong point in south-eastern Italy. A southward extension of the Via Appia brought it within the Roman road network by 244 BC (a final stretch of the Via Appia then ran east from Taranto to Brindisi on the Adriatic coast), and it probably acquired an enhanced administrative standing with the Augustan reorganization of Italy (around 7 BC) and was the natural centre for his second region.

Taranto was certainly the capital of the late Roman province of Apulia et Calabria, the second region’s successor in the Diocletianic scheme of things (AD 297). But by then the town was suffering from the economic downturn that was affecting the empire as a whole, and the urban component in particular. In Taranto’s case it is possible that the rot set in as early as AD 109, when a new road from BENEVENTO to Brindisi, the Via Traiana, was opened; this cut Taranto out of a loop that carried much of the traffic between Rome and the East. Not that Roman Taranto was ever that prosperous: even allowing for the fact that it still lies buried beneath the modern town, it has produced surprisingly little in the way of monuments.

The last mention of classical Taranto dates to AD 547. The city wall must have deteriorated by then, because Procopius records that the East Roman general sent to occupy the town remarked that it was ‘entirely without defences’ and had to content himself with refortifying the citadel (De bello Gothico, VII.23.12). The tale of Taranto had come full circle.

As to population, the classical Greeks’ liking for vast perimeters makes it difficult to gauge Taranto’s size. The conspicuous military weakness of the Tarentine state is probably the best pointer; it suggests that the population never topped 20,000, which makes something under 10,000 a probable maximum for Taranto town. On the other hand, it seems unlikely that the town had fewer than 5,000 to 6,000 inhabitants in its best years, say between 350 BC and AD 150.